Five years after warning that housing affordability was nearing a breaking point, Clallam County’s commissioners are still blaming the crisis—while quietly fueling it. Guest contributor Jake Seegers notes that as home prices soar, the commissioners have backed policies transferring over 50,000 acres from private ownership into state, corporate, and conservation control. From Meta-funded carbon forests to taxpayer-financed easements, land once supporting local families and businesses is being locked away in the name of “climate” and “sustainability.” The result? A shrinking land base, record prices, and leaders determined to conserve everything—except affordability.

By Jake Seegers, guest contributor

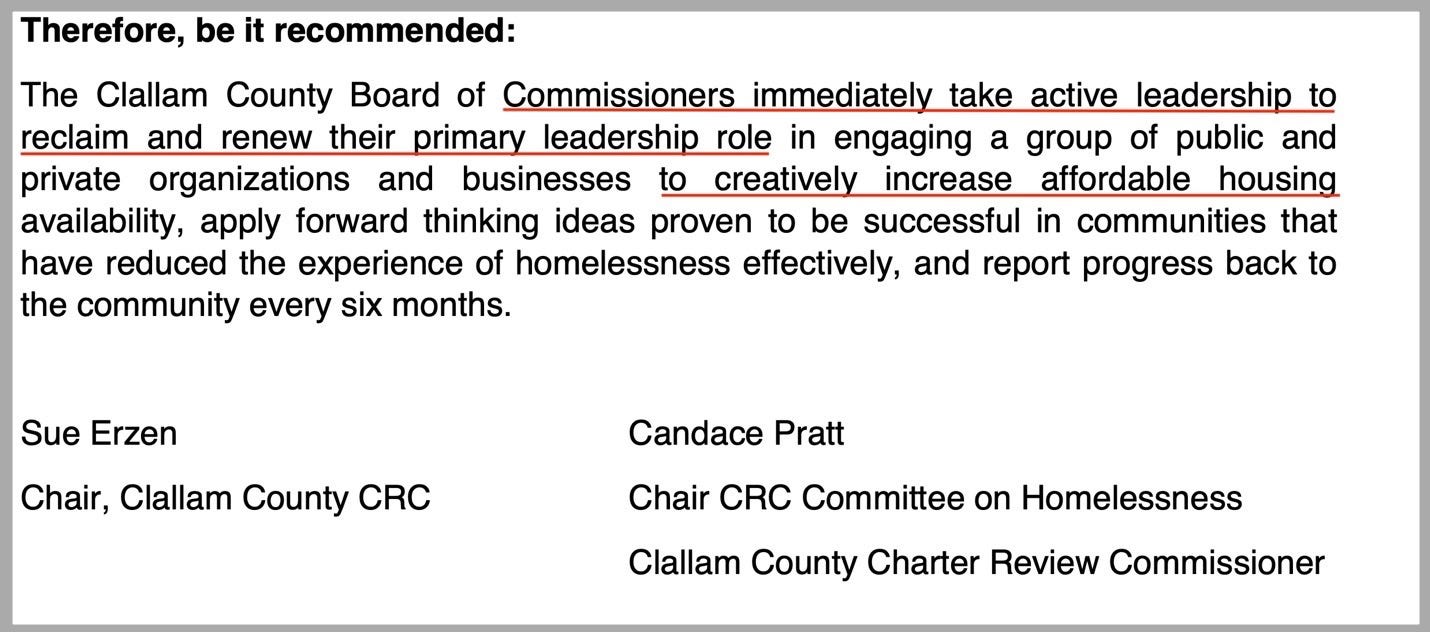

On September 16, 2020, the Charter Review Commission sent a letter urging the Clallam County Board of Commissioners to take immediate action on housing affordability.

Since then, home prices have surged roughly 50 percent, according to estimates from the Washington Center for Real Estate Research and Redfin. During a July 8 board meeting, Commissioner Randy Johnson conceded that the problem has only grown worse:

“In Clallam County, it continues to rise to probably the No. 1 issue for most county residents — the shortage of housing, and/or the affordability of housing, and/or the percentage of one’s income that one needs to allocate to help pay for housing.”

Yet, even as they acknowledge the crisis, all three commissioners continue to champion conservation policies that steadily remove land from private ownership.

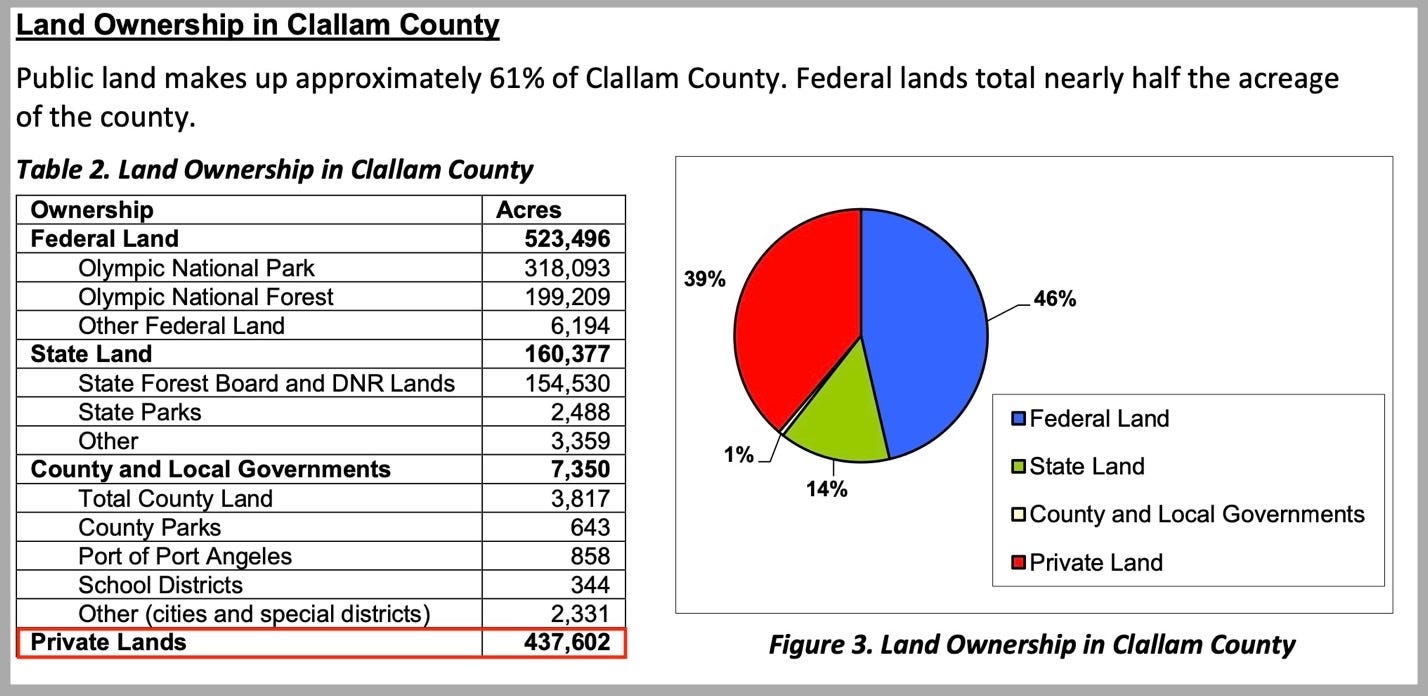

In the past five years alone, more than 50,000 acres — over 11% of Clallam’s 437,600-acre private land base — have been absorbed into conservation holdings.

The Doc Holliday Dilemma

Twenty-five miles west of Port Angeles, a sharp bend on Highway 112 marks a familiar milestone for local surfers — Twin Rivers Beach and its clean waves are just ahead.

Directly south of that bend lies Doc Holliday Unit 5 — timberland owned and managed by Washington State’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Webster Logging, the sole bidder in DNR’s Doc Holliday timber auction, was awarded Unit 5 as part of a larger state-managed harvest.

But on August 24, 2024, state land — and the contractual rights of a local logging company — were violated. Protesters entered the sale area, stripped DNR boundary markers and placards, and later delivered them to DNR headquarters in Olympia, along with a letter of protest.

Removing or defacing DNR boundary markers is a misdemeanor under RCW 76.48.150, yet the activists appeared to gain influence rather than face consequences.

Instead of facing accountability, their tactics earned an audience with an ally when Commissioner Mark Ozias invited Brel Froebe, Director of the Center for Sustainable Forestry, to deliver a two-hour presentation during the October 6, 2025, work session. Froebe proposed a “replacement sale option” that would place 45 acres of Doc Holliday into permanent conservation.

The “Replacement” Mechanism

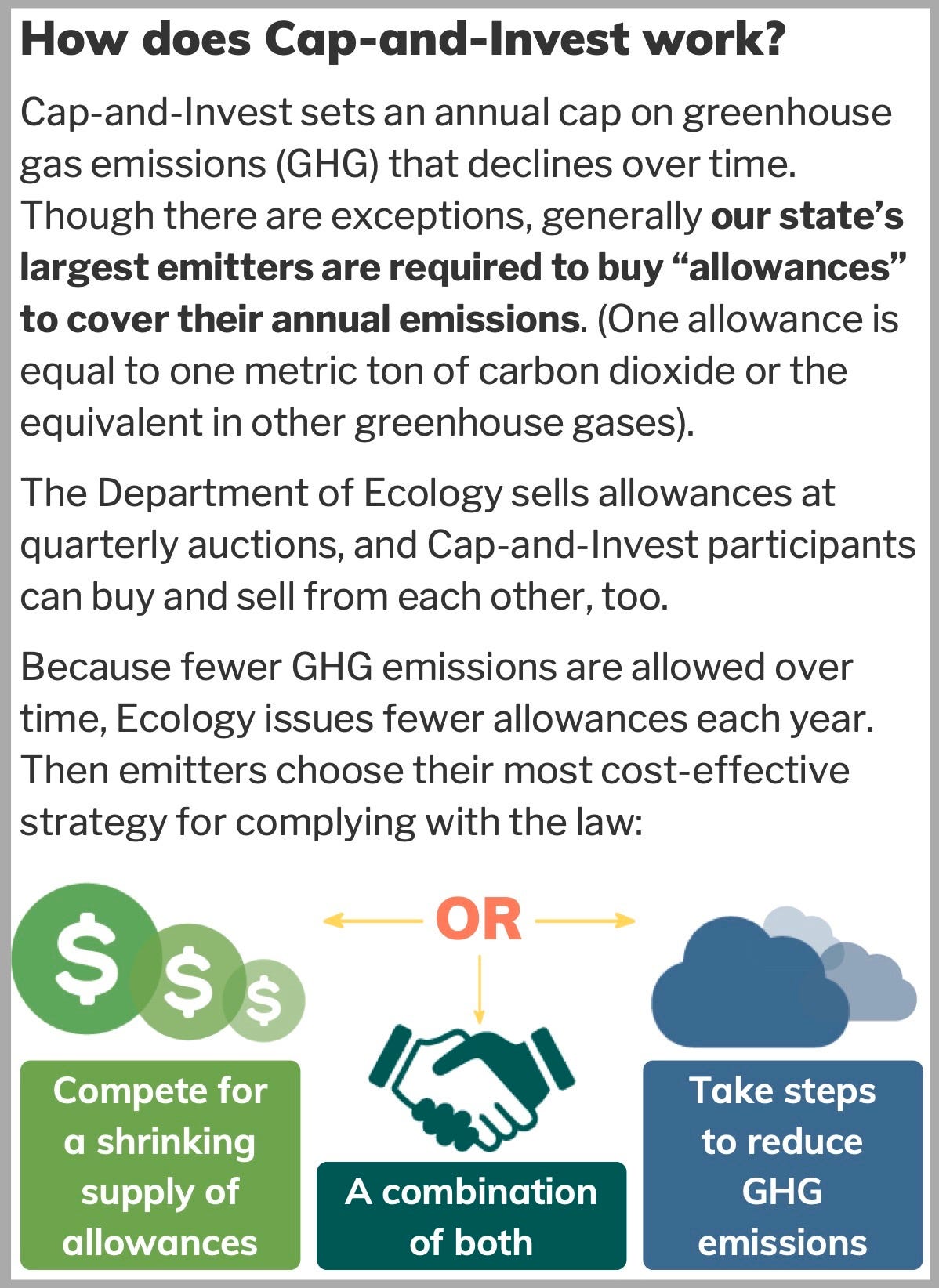

The proposal relies on funding from the Natural Climate Solutions (NCS) account, created under Washington’s 2021 Climate Commitment Act.

The Climate Commitment Act (CCA) compels the state’s largest carbon-emitting industries — refineries, utilities, manufacturers, and large landfills — to purchase a shrinking annual supply of carbon allowances. Think of it as an ever-increasing tax on essential services. As those costs rise, utilities and businesses pass them directly to customers.

The CCA didn’t just drive up utility bills — it helped make Washington’s gasoline the most expensive in the nation.

A portion of the auction revenue flows to DNR’s NCS account, which then uses those dollars to purchase private timberland to replace acreage removed from harvest through conservation.

In effect, Washington residents bear the burden of rate hikes on energy and fuel, while DNR uses those proceeds to bid against private buyers for land — driving up timberland prices and, ultimately, the cost of homeownership.

The commissioners have already supported similar efforts for NCS-funded replacements for DNR’s Shore Thing and Power Plant units. Whether they move forward with Froebe’s Doc Holliday proposal remains to be seen.

The Economic Backfire

If commissioners approve the Doc Holliday replacement plan, DNR will need to purchase roughly 90 acres of new timberland — double the 45 acres removed — to maintain or grow trust revenue.

During the work session, Commissioner Mike French remarked that these replacement purchases should focus on parcels “at risk of conversion” — real-estate shorthand for developable land:

“If we’re targeting acres and bringing them into the trust, we should be doing that from a standpoint of: ‘How do we prevent conversion?’”

But shifting privately held, buildable land into state ownership shrinks the supply. And when supply shrinks while demand stays constant, prices rise and affordability declines — the very opposite of the commissioners’ stated housing goals.

Preserving 45 acres of mature forest may sound noble, but the consequence is a tighter land market and steeper barriers for working families trying to buy a home.

The Conservation Futures Machine

In 2019, Commissioners Johnson and Ozias established a new Conservation Futures Tax, setting the levy at $0.0275 per $1,000 of assessed value.

In May 2025, the board unanimously committed $1.5 million from that fund to the North Olympic Land Trust (NOLT) for conservation easements on 172 acres at Cameron Farm Estates and Heifer Farm.

NOLT now manages, owns, or holds easements on roughly 3,900 acres countywide. Conservation land or land controlled by conservation easements typically qualify for significantly reduced property taxes or outright exemption under RCW 84.34 and RCW 84.36.260. That shifts the burden of funding things like schools, libraries, hospitals, and county government onto other taxpayers.

The Meta Forest

NOLT’s footprint, however, pales beside the scale of modern “climate-finance” conservation.

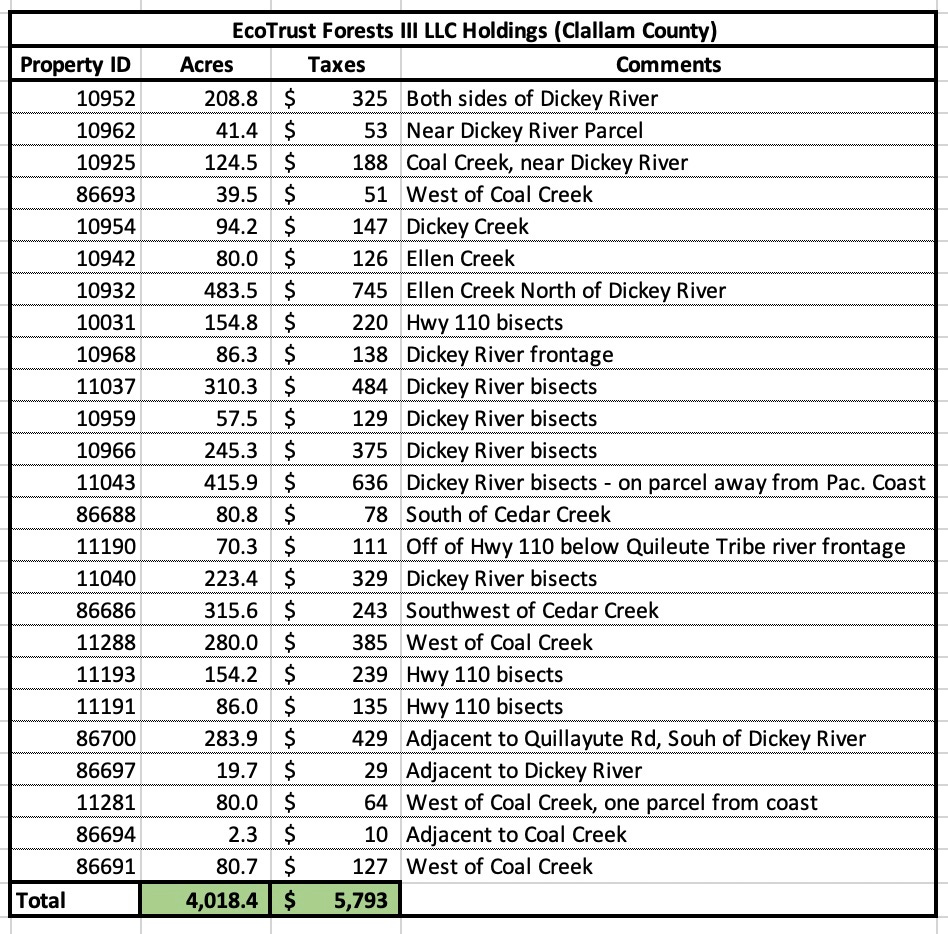

In early 2025, EFM Investments, a Portland-based “climate-smart forestry” firm, purchased 37,000 acres in Clallam County as part of a 68,000-acre Olympic Peninsula portfolio backed by Meta, Facebook’s parent company.

That acquisition — motivated by carbon-credit markets — effectively transferred tens of thousands of acres from private, harvestable management into corporate-offset conservation.

In letters of support, commissioners have advocated for EFM’s unquenchable appetite for private forestland.

The Expanding Conservation Empire

EFM began as a branch of Portland’s EcoTrust, and its reach into Clallam County is far from small. Through EcoTrust Forests III, LLC, it owns more than 4,000 acres locally—plus another 2,350 acres under the name LC Restoration, LLC.

And they aren’t alone.

Although not directly endorsed by the commissioners, The Nature Conservancy—which boasts of conserving 125 million acres worldwide—has quietly acquired nearly 2,000 acres of prime Hoh River frontage right here in Clallam County.

Together, these holdings represent a growing shift of local land into institutional and corporate control, often financed by out-of-state investors and international carbon markets.

So when housing affordability is at an all-time low, and homeownership remains out of reach for many Clallam residents, the question practically asks itself:

Why have our commissioners embraced the wholesale transfer of private lands to mega-corporations, global climate interests, and state agencies—entities that use taxpayer-funded programs to bid against the very taxpayers who fund them?

The Bigger Picture

Despite acknowledging that housing affordability is Clallam County’s top issue, the commissioners continue to applaud policies that erode the private land base.

From local farmland easements to 200 million dollar carbon-motivated acquisitions, every new conservation deal removes taxable, buildable land from circulation — tightening the market and raising the cost of living.

It’s a paradox that shouldn’t be lost on voters: the more land our leaders protect, the fewer residents can afford to call Clallam County home.

Last Sunday, Jake Seegers asked readers if they believe Clallam County has a revenue problem or a spending problem. Of 183 votes:

85% said, “Spending problem”

2% said, “Revenue problem”

14% said, “Both”

No one said, “Neither / unsure”