Miguel Angel Medel Lopez was deported from the United States multiple times, convicted of serious sexual crimes against young children, and still managed to return to Clallam County — where the public is now paying to prosecute him all over again. As indigent defense costs continue to rise and court resources are strained by retrials, this case exposes systemic failures that left children vulnerable and taxpayers footing the bill.

The Victims Must Come First

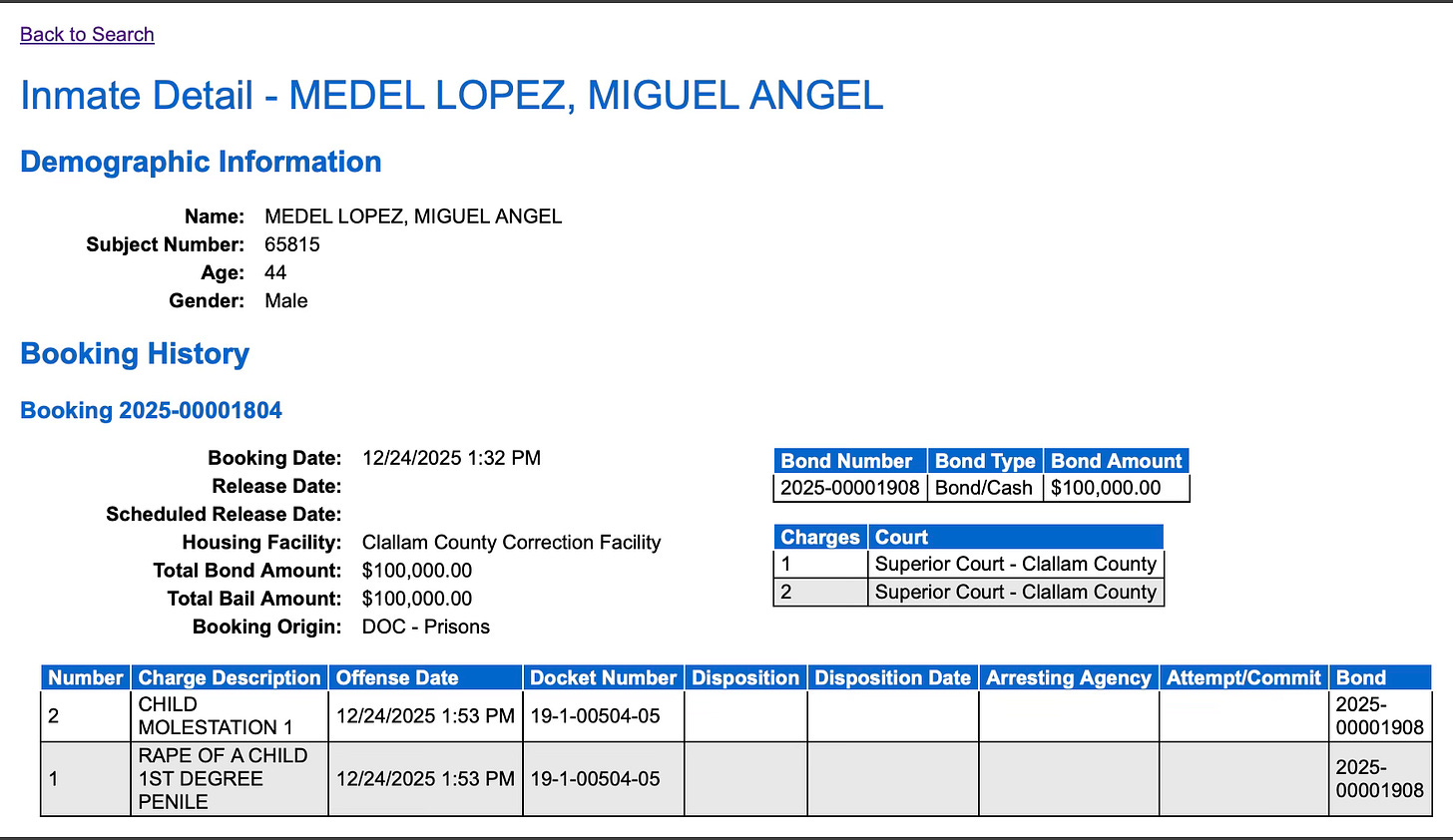

On Christmas Eve, Miguel Angel Medel Lopez, 44, was booked into the Clallam County Jail on charges including first-degree rape of a child and first-degree child molestation.

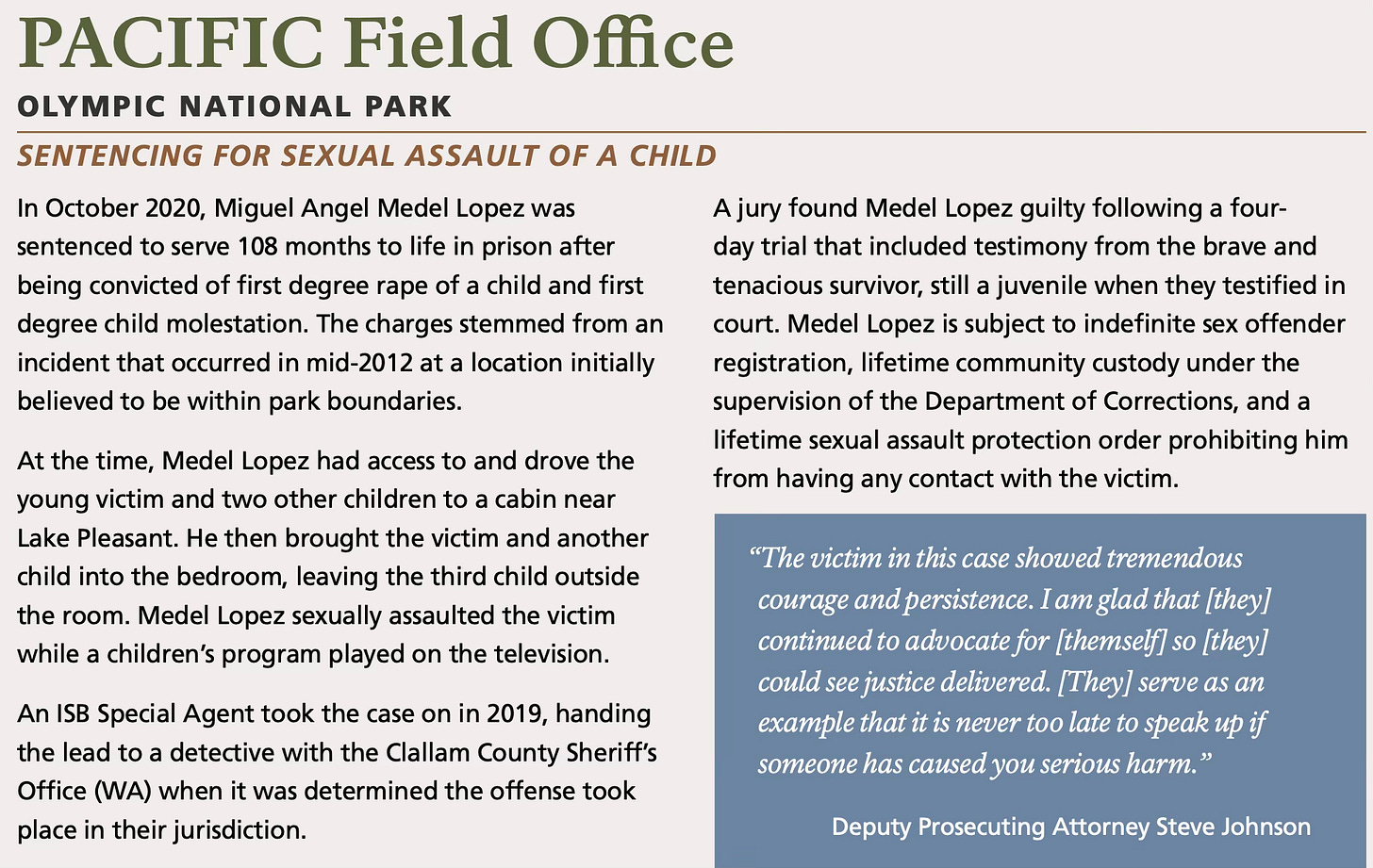

The crimes at the center of the case occurred in 2012 and involved two children, ages 6 and 8 at the time.

According to investigators and court records, Medel Lopez took the children to a secluded cabin in the woods. There, prosecutors allege, he committed sexual acts that meet Washington’s highest statutory thresholds for child rape and child molestation — crimes defined by coercion, exploitation, and extreme abuse of trust.

One of the victims later disclosed the abuse to a mental health professional, triggering a lengthy investigation involving Child Protective Services, the National Park Service, and the Clallam County Sheriff’s Office. As is often the case with child sexual assault, the disclosure came years after the harm occurred.

The passage of time does not lessen the seriousness of what happened — and it does not undo the damage done to the children involved.

Blaming the Children

Court records describe a recorded conversation in which one of the victims confronted Medel Lopez. Rather than accept responsibility, he attempted to shift blame onto the children themselves.

“I didn’t force you to do anything,” Medel Lopez said, according to court documents.

“It was the way you guys were playing before. With me. It made me do it.”

That statement is not editorial interpretation. It is drawn directly from court filings and contemporaneous reporting and was part of the evidentiary record presented at trial.

He went on to say he would “probably” take it back if he could, adding, “I don’t want to live with that over my head. I can’t fix the past, but I can probably do better in the future.”

For prosecutors, those statements illustrated the severity of the crimes and the lack of accountability. For the public, they underscore why child victims require firm protection — and why system failures carry such lasting consequences.

Removed Again and Again — Then Back Here

Medel Lopez is a citizen of Mexico. Records show he was removed from the United States multiple times:

June 2005: Arrested near Lukeville, Arizona, and returned to Mexico.

Later that same month: Arrested again near Sasabe, Arizona, and returned to Mexico.

March 2006: Convicted of assault in Clallam County, sentenced to jail, then turned over to immigration authorities and returned to Mexico.

Each time, he came back.

At some point after those removals, Medel Lopez re-entered the United States without inspection and eventually settled in Forks, Clallam County.

That raises an obvious question: why here?

Clallam County is remote, rural, and far from the southern border. Reaching it is not accidental. The record does not explain why Medel Lopez chose this community, but it is reasonable to ask whether weak enforcement and generous public support systems play a role in where repeat offenders ultimately land.

Living Here — on the Public’s Dime

Once in Clallam County, Medel Lopez became eligible for taxpayer-funded systems. These include:

Court-appointed indigent defense

Public or subsidized housing

Free or reduced-cost public transit

Publicly funded food programs

County-supported harm-reduction services, including drug-use supplies

Individually, these services exist to prevent hardship. Collectively, they form a safety net that often operates with little connection to enforcement or accountability — even when individuals repeatedly violate the law.

For working residents struggling with housing costs, rising taxes, and stretched public services, the imbalance is increasingly hard to justify.

The Cost of Doing It All Over

Medel Lopez was convicted and sentenced to a minimum of nine years in prison. But in October, a Washington appellate court reversed that conviction and ordered a new trial, citing legal errors serious enough to require starting over.

The practical effect is straightforward: Clallam County must prosecute the same crimes again.

A retrial means renewed expenses for:

Prosecutors

Judges and court staff

Expert witnesses

Jail operations

And once again, publicly funded indigent defense

Indigent defense is already one of the fastest-growing costs in Clallam County’s budget and has been cited repeatedly by county leadership as a major contributor to projected deficits. State mandates are expected to push those costs even higher.

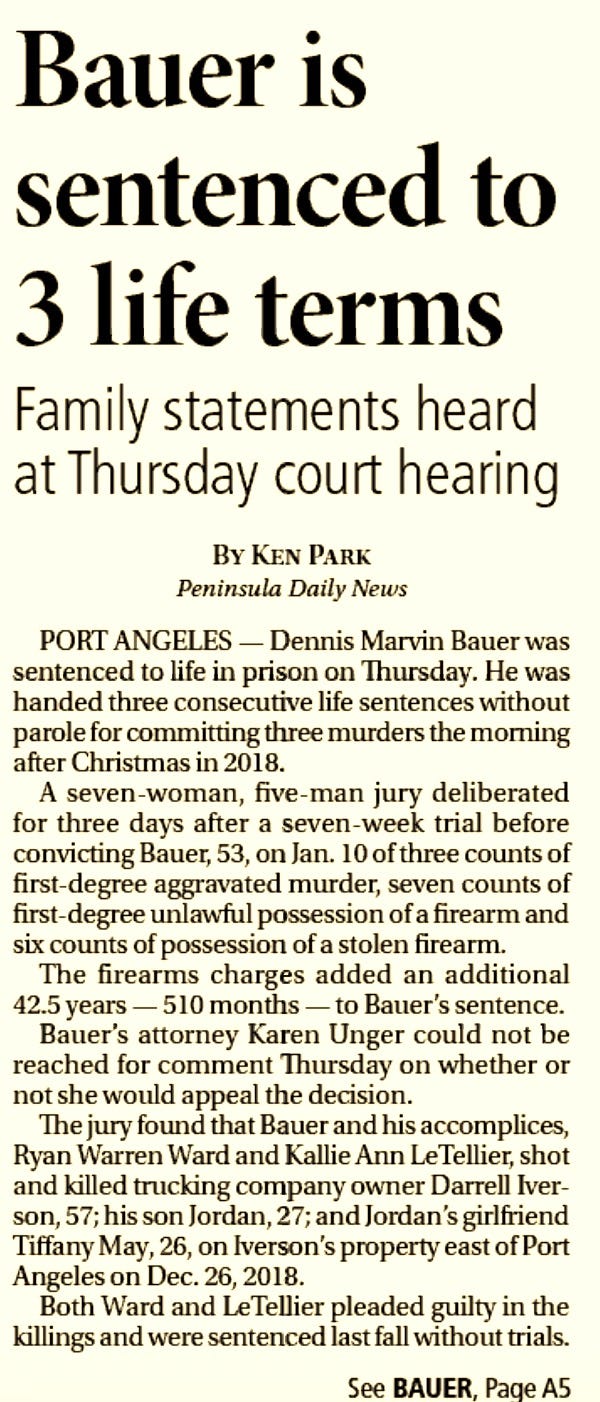

This retrial comes as the county is also preparing for an expensive murder retrial in a separate case — another example of how legal failures translate directly into public expense.

Residents are routinely told these costs are unavoidable. What is rarely explained is why such failures keep happening, or why prevention and enforcement consistently take a back seat.

Unanswered Questions and Quiet Costs

Medel Lopez has also pursued civil rights lawsuits against Clallam County, alleging violations related to his prosecution and confinement. Those claims were dismissed by the courts, which found no civil rights violations. The result followed a familiar pattern: serious criminal conduct, public expense, failed civil litigation — and now another taxpayer-funded trial.

He was transferred back to the Clallam County Jail on December 24, a time when public attention is limited and news coverage is thin. That timing may be coincidental, but it underscores a recurring problem: residents often learn about the financial and public-safety consequences of these cases only after the costs are locked in.

The case leaves several uncomfortable but necessary questions unanswered.

Why do individuals who have been removed from the country multiple times continue to return and remain in Clallam County?

Why are local taxpayers repeatedly paying for retrials in the most serious criminal cases?

Why do court errors rise to a level that overturns convictions involving child rape?

And why are the fiscal and public-safety impacts of these failures so rarely discussed openly?

A Way Forward That Puts the Public First

Cases like this shouldn’t be dismissed as flukes. When the same breakdowns repeat — deportations ignored, convictions overturned, retrials funded by taxpayers — they point to deeper problems.

Repeat deportation has to mean something. When someone has been removed multiple times and then returns, commits violent sexual crimes, and settles here, the burden should not automatically fall on local taxpayers. County leaders should be pressing state and federal partners to enforce immigration detainers in cases involving serious crimes — and be transparent when those systems fail.

Courts must also be held to a higher standard in the most serious cases. When convictions for child rape are overturned due to legal errors, the damage is real: victims are retraumatized, and the public pays again. Independent review of major reversals should be routine, with clear explanations provided to the public.

Indigent defense costs need context and accountability. If this is one of the county’s fastest-growing expenses, residents deserve honest answers about why repeat cases keep cycling through the system and what is being done to prevent them.

Finally, public services must come with real boundaries. Housing assistance, free transit, food programs, and harm-reduction services were never meant to enable repeated lawbreaking or shield dangerous behavior. Compassion that ignores public safety is not compassion — it’s negligence.

None of this undermines due process. It strengthens it.

Justice is not measured by how many times a case can be retried or how much money can be spent after the fact. It is measured by whether children are protected, laws are enforced, and failures are addressed before they happen again.

Clallam County can do better — but only if it chooses accountability over complacency and transparency over silence.