From coastline mapping already done with federal data, to neighborhoods flooding after “restoration,” to NGOs and advisory boards operating with little transparency, Clallam County residents are again left asking the same question: Who is this system really working for? This potpourri examines government partnerships that defy common sense, harm-reduction policies that externalize costs onto businesses and neighborhoods, and nonprofit financial reporting that raises more questions than it answers. None of this is conspiracy. It is public record — and it deserves public scrutiny.

A Coastline Already Mapped — So Why Map It Again?

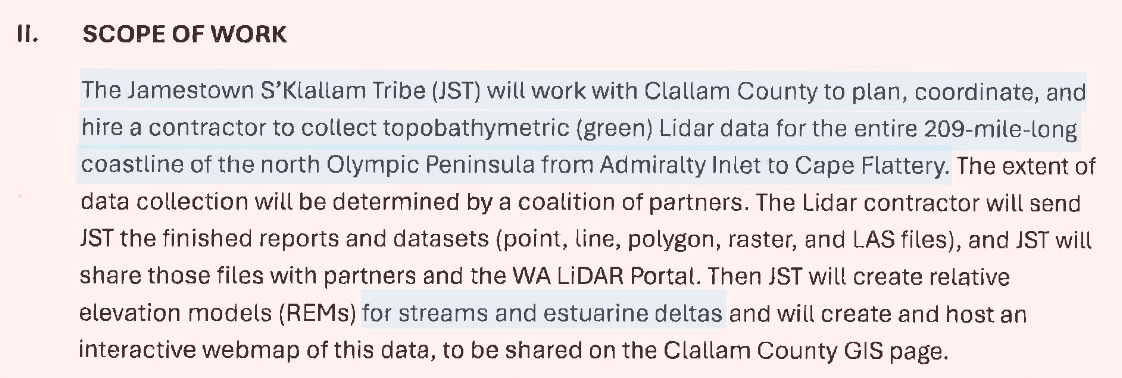

Clallam County has announced a partnership with the Jamestown Corporation, a subsidiary of a sovereign nation, to map the entire 209-mile coastline from Cape Flattery to Admiralty Inlet. The stated purpose is to develop models for “estuarine deltas.”

What goes unexplained is why this mapping is needed at all.

High-resolution coastal lidar and bathymetric data already exist through federal agencies. NOAA and USGS have produced detailed topobathymetric models of the Strait of Juan de Fuca using integrated airborne and vessel-based lidar systems. These datasets—used for tsunami planning, coastal management, and habitat studies—are publicly accessible through NOAA Digital Coast and USGS ScienceBase.

So the question is unavoidable: why repeat work that has already been done, unless different outcomes are desired?

The county’s past experience with estuarine “restoration” offers a cautionary tale. Meadowbrook Creek in Dungeness was restored through a county-Jamestown partnership that included removing an armored dike protecting nearby homes. The day after the ribbon-cutting ceremony, homes flooded. Those same homes have flooded nearly every winter since.

This Saturday, the adjacent Three Crabs neighborhood flooded again.

These are not disputed facts.

They matter because the Jamestown Corporation serves as a fiscal agent for the Strait Ecosystem Recovery Network (SERN).

At a 2021 SERN workshop, participants discussed purchasing beachfront properties at devalued prices, partially by influencing the Comprehensive Plan. The North Olympic Development Council (NODC) was identified as a partner in that effort.

NODC’s president is County Commissioner Mark Ozias.

The Jamestown Tribe funded 53% of Commissioner Ozias’ most recent campaign.

NODC is an NGO involved in shaping the Comprehensive Plan outside of public view.

The Marine Resources Committee has called for the removal of Three Crabs Road and the relocation of roughly 600 residents.

The MRC is chaired by Jamestown tribal member LaTrisha Suggs who is also employed by the Jamestown Corporation as a restoration planner.

Commissioner Ozias has said he will not address the MRC’s call to relocate resident of Dungeness until the Comprehensive Plan is released.

A sovereign nation wants beachfront property.

A restoration project increased flooding.

County government will not intervene to protect residents.

That is not a theory. It is Clallam County governance in practice.

Monday Morning Cleanup, Courtesy of Local Businesses

Monday mornings near the Clallam County Courthouse follow a familiar routine. Businesses arrive early—not to open shop, but to remove trash, needles, and encampments that proliferated over the weekend.

A subscriber shared photos from outside Frontier Title, adjacent to Safeway on Lincoln Street. The area has become an open-air drug use and sales zone with little fear of consequence.

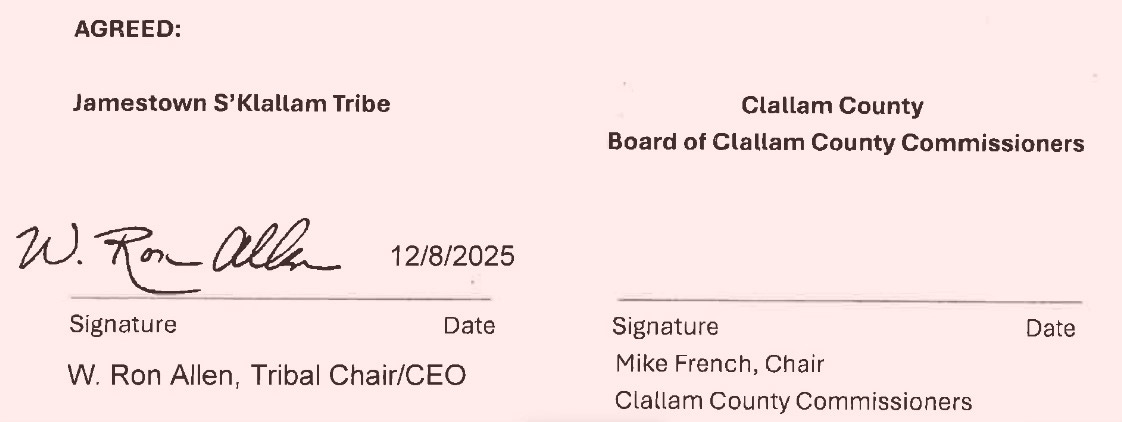

County policy plays a role. Drug paraphernalia is freely distributed in the name of harm reduction. The supplies are called “free,” but the cost is borne by businesses that pay taxes, clean sidewalks, and absorb the damage.

Compassion is not cost-free. The county has simply shifted those costs onto private citizens.

Food for Thought at the Sequim Food Bank

The Sequim Monitor’s in-depth review of the Sequim Food Bank’s executive director job posting and 2024 annual report raises thoughtful, data-driven questions that deserve answers.

The Food Bank is hiring an executive director at $90,000–$105,000 annually—up to 2.6 times the average income in Sequim. Benefits include healthcare, retirement match, stipends, and generous leave.

Higher wages can strengthen the local economy. But transparency matters, especially for nonprofits reliant on public trust and donations.

The Sequim Monitor highlights inconsistencies in the annual report, including unexplained differences in totals, unclear categorization of salaries, discrepancies in in-kind donation reporting, and percentages that do not mathematically align.

Also worth noting: Commissioner Mark Ozias serves as president of the Sequim Food Bank.

Readers should subscribe to the Sequim Monitor for continued reporting. These are fair questions asked respectfully—and they deserve clear responses.

An “Umbrella” for Harm Reduction

Commissioner Ozias recently briefed the public on Salish Behavioral Health, of which he sits on the executive board, describing it as a regional “umbrella” organization for Clallam, Jefferson, and Kitsap counties.

This year’s priorities include more detox beds, transportation, expanded peer support—and “more harm reduction.”

Translated: more distribution of drug paraphernalia.

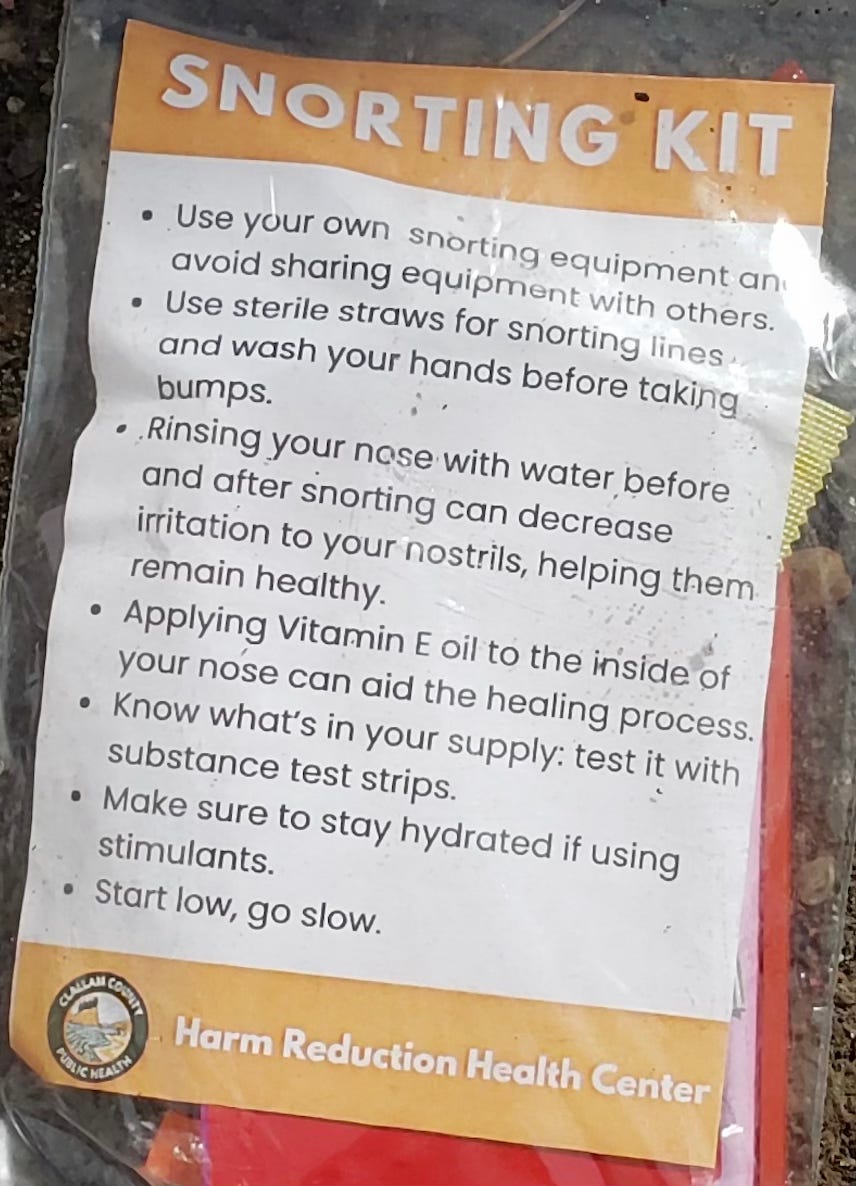

National data paints a sobering picture. According to aggregated drug abuse statistics, overdose deaths have surged alongside expanded harm-reduction-only strategies. Even deeply progressive jurisdictions are re-examining these policies as public disorder, addiction, and fatalities worsen.

Harm reduction without treatment, accountability, and recovery pathways is not compassionate. It is abandonment.

Harm Reduction Is Not a Magic Pill

Marolee Smith’s recent Substack essay provides essential historical context missing from today’s debate.

Harm reduction was never intended to stand alone. It was designed as a supporting tool within a comprehensive system that emphasized treatment, community involvement, accountability, economic opportunity, and prevention.

What we have today is the hollowed-out version: supplies without structure, compassion without responsibility, and policy without outcomes.

Smith’s writing is a reminder that we did not arrive here by accident—and that better models already exist.

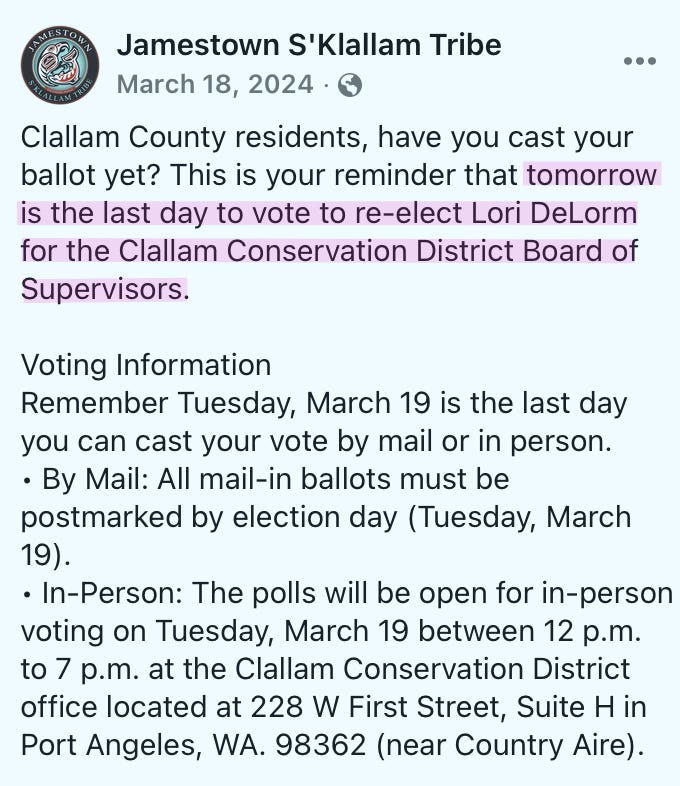

When Government Tells You How to Vote

A Thurston County judge recently voided the election of a Clallam Conservation District board supervisor. Separately, during that same election, the Jamestown Tribe used its official Facebook page to publicly urge voters to support a specific candidate.

That is a sovereign government directing votes in a local election.

Jamestown Corporation CEO Ron Allen has stated that the Jamestown Tribe is a public entity. Government endorsement of a candidate—without presenting alternatives or positions—raises serious questions. Federal, state, and local governments may not use public authority to direct voters to support or oppose a candidate. However, apparently, a sovereign nation can.

The Conservation District has since moved to mail-in voting by request only. Citizens can request ballots at clallamcd.org. The next public board meeting is January 13, 2026, in Port Angeles.

Participation matters—especially now.

Where the Real Debate Happens

CC Watchdog articles often come alive in the comments.

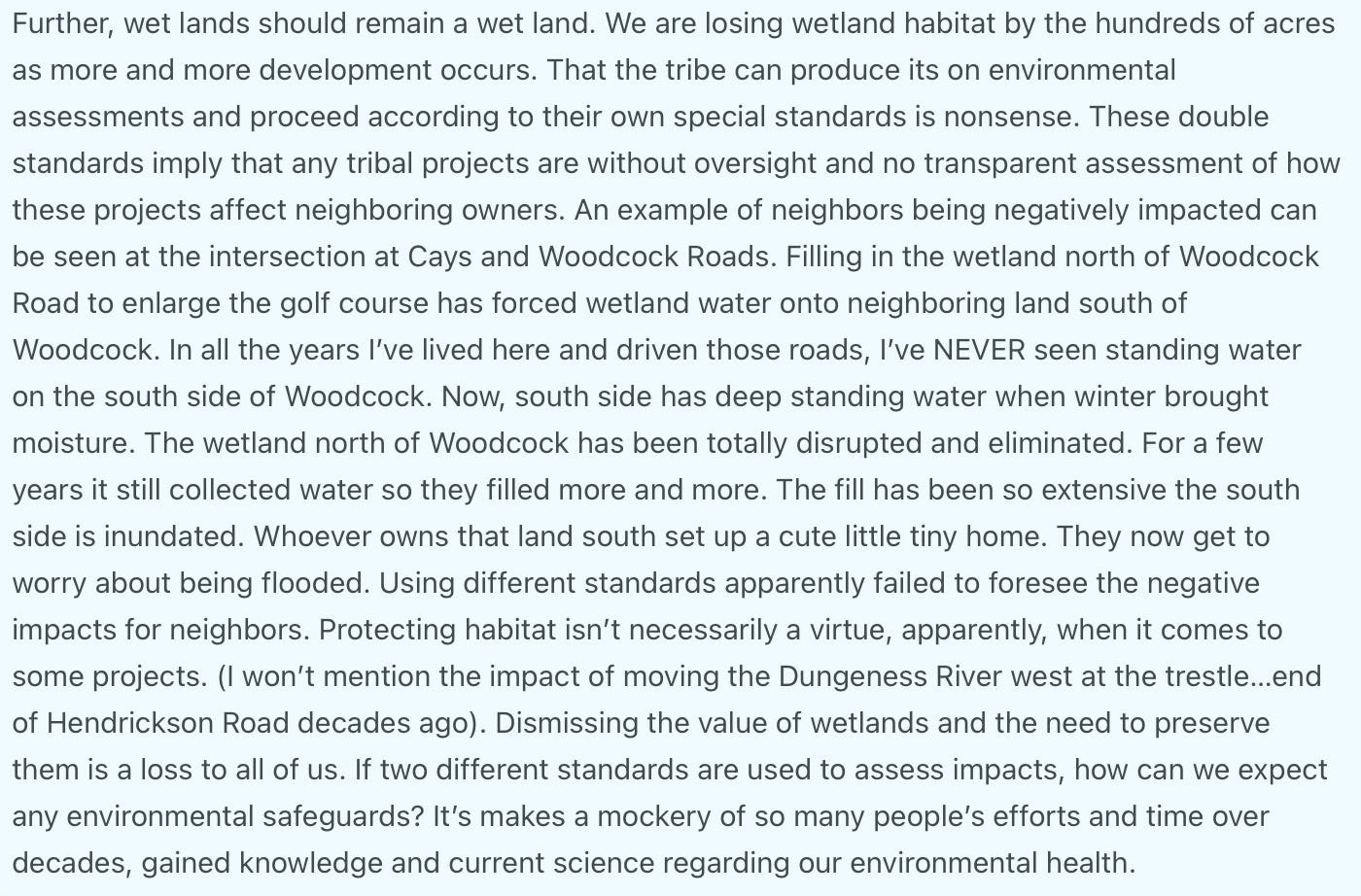

Subscriber Kathleen’s detailed account of wetland fill near Cays and Woodcock Roads illustrates how projects approved under different standards can impose real harm on neighbors. Wetlands once absorbed water. After extensive fill to expand the Jamestown Corporation’s golf course, the water now inundates adjacent properties.

If environmental protections apply to some but not others, they protect no one.

When Help Hurts

Don’t Feed the Ducks: It Makes Them Dependent uses a simple true story from Ashland, Oregon to deliver a serious lesson. Well-meaning residents fed ducks in a public park, believing they were helping. Instead, the ducks stopped foraging, clustered unnaturally, and became dependent on humans for survival. The solution was not cruelty, but restraint—ending the feeding so the ducks could relearn how to survive on their own.

The story’s message is direct: help that replaces independence ultimately harms the very beings it intends to protect. True care preserves capability, responsibility, and resilience, rather than removing them.

That lesson resonates uncomfortably in Clallam County’s approach to homelessness and harm reduction. An expanding web of free services—often offered without expectations around treatment, recovery, or transition—risks creating long-term dependency rather than pathways back to stability. Compassion matters, but when it is disconnected from accountability and independence, it can quietly undermine both individuals and the community meant to support them.

Scanner Reality Check

A sampling of recent Clallam County Scanner Report entries underscores what residents already know: violent incidents, overdoses, and disorder are not abstract policy debates. They are daily events.

Ignoring that reality does not make it go away.

The Sticker That Says It All

An eBay seller is offering “Port Angeles” stickers depicting a burned-out RV surrounded by trash and transients. The stickers cost $6 and reviews are glowing. One even calls it “ideal for use on laptops.”

You probably won’t find one on the commissioner’s county-issued laptops—but perhaps the satire hits close enough to sting.