In this deep-dive investigation, Jake Seegers uncovers how Clallam County’s health bureaucracy is funding its own research to justify the very harm-reduction programs that have coincided with skyrocketing overdoses, higher ER visits, and the loss of federal support. While county officials scramble to protect their narrative — even paying for a “gaps study” designed to validate existing policies — the data tells a different story. The only proven life-saving results come from Operation Shielding Hope, a paramedic-led intervention that county leadership barely acknowledges. This exposé reveals the conflict of interest driving county policy, the misuse of opioid-settlement funds, and the firsthand accounts of survivors who say harm reduction kept them trapped — not safe.

Conflict of Interest

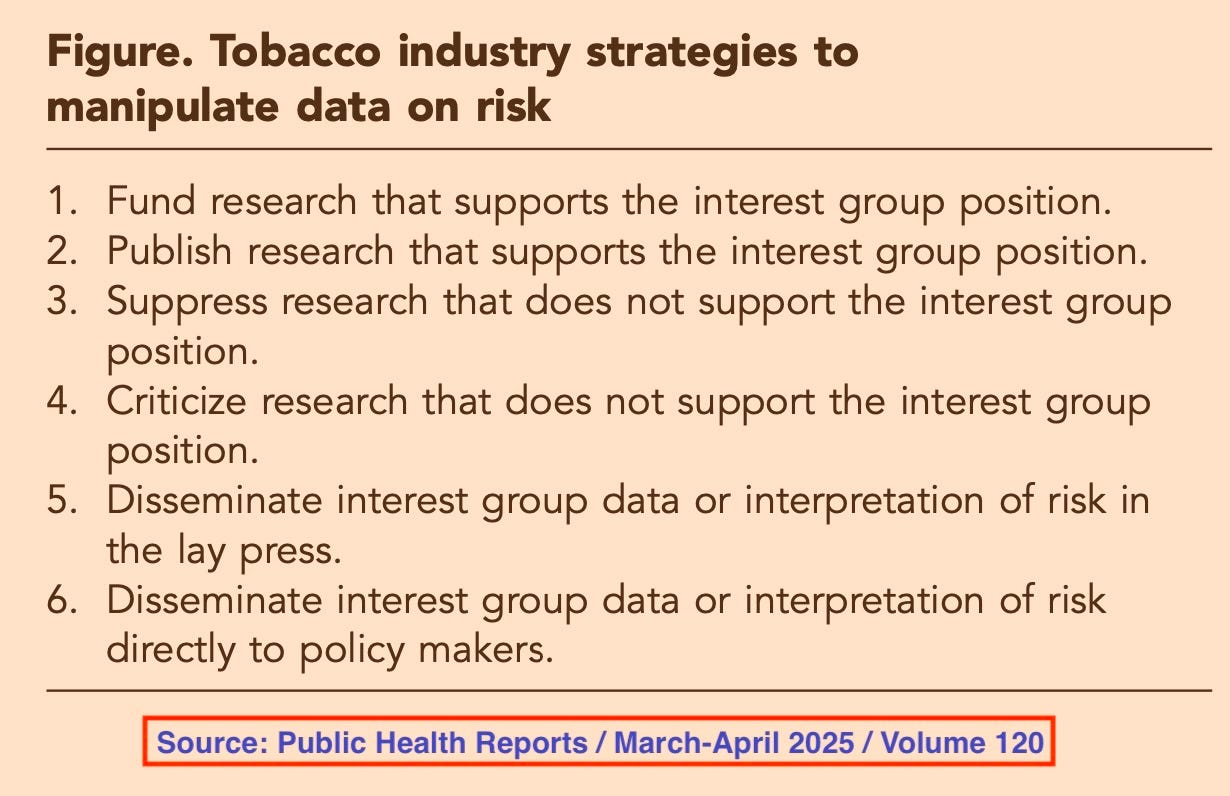

In 2005, Dr. Lisa Bero published “Tobacco Industry Manipulation of Research” in Public Health Reports, the official journal of the U.S. Surgeon General. Her warning was blunt: when industries fund research into their own products, they shape the evidence to protect their profits.

“Research findings or ‘facts’ are subject to interpretation,” she wrote. “Interest groups… construct the evidence about a health risk to support their predefined policy position.”

She then outlined the standard playbook:

Today, these tactics are mirrored in Clallam County’s harm-reduction establishment — from Allison Berry (who serves as the health officer for both Clallam and Jefferson counties), to the Clallam County Board of Health, to Health and Human Services, and ultimately the county commissioners who continue to fund the harm-reduction agenda without scrutiny.

Funding the Narrative

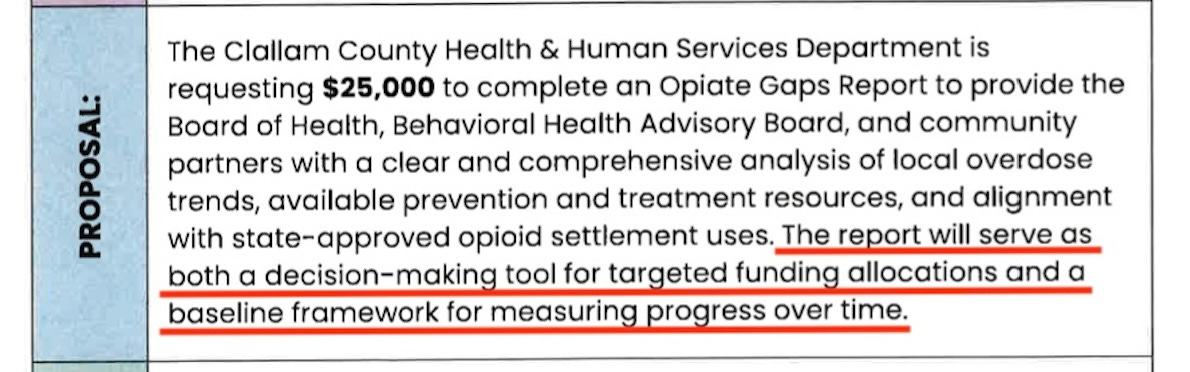

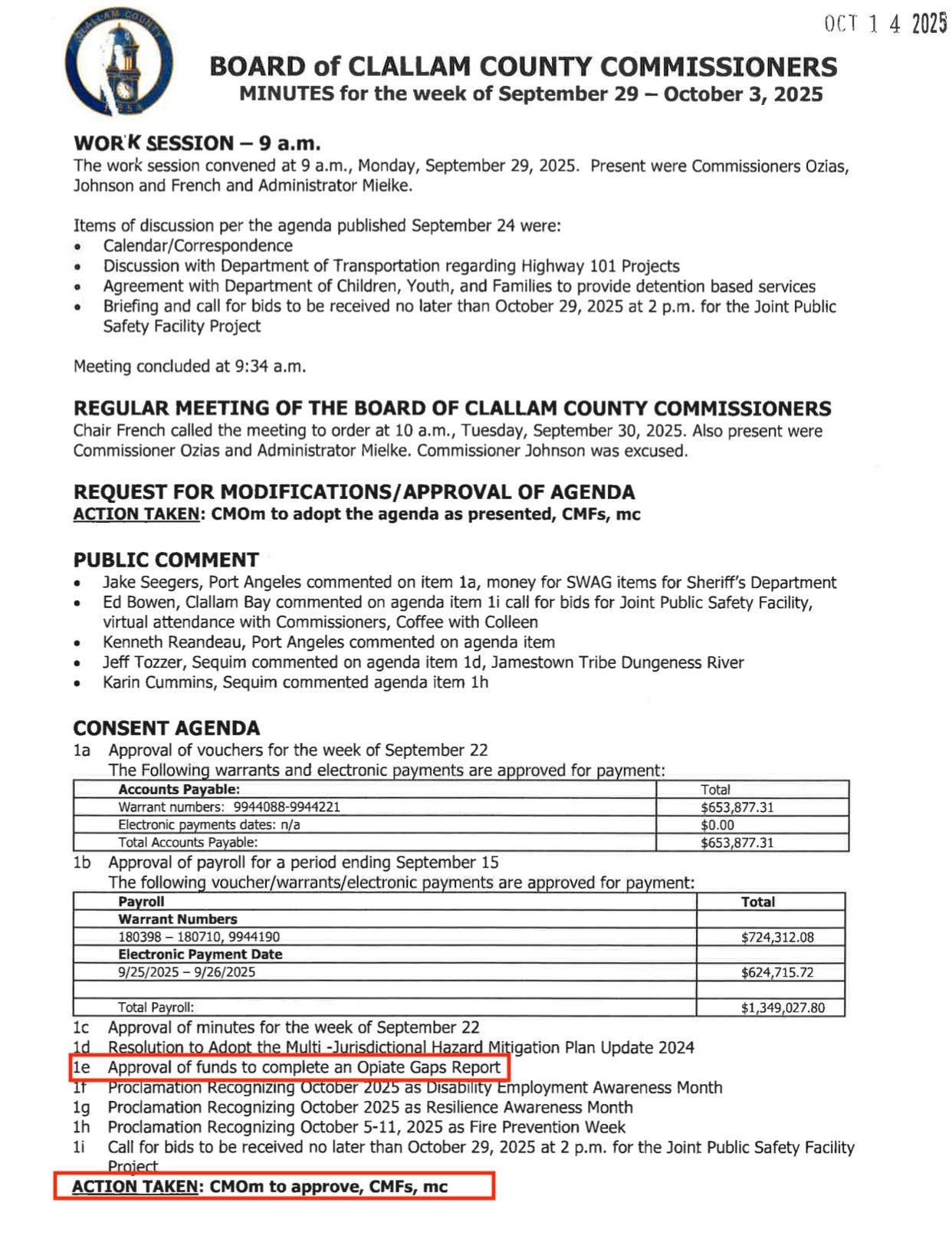

At the September 22 work session, Clallam County Health and Human Services (CCHHS) requested $25,000 to produce an “Opioid Gaps Report,” which they described as a “decision-making tool” for future funding.

In other words, Health and Human Services asked the commissioners for funding to produce the very data they will later use to justify more spending on harm reduction.

Commissioner Randy Johnson responded, “I think this is great,” and the commissioners approved the request the following week — despite the glaring conflict of interest.

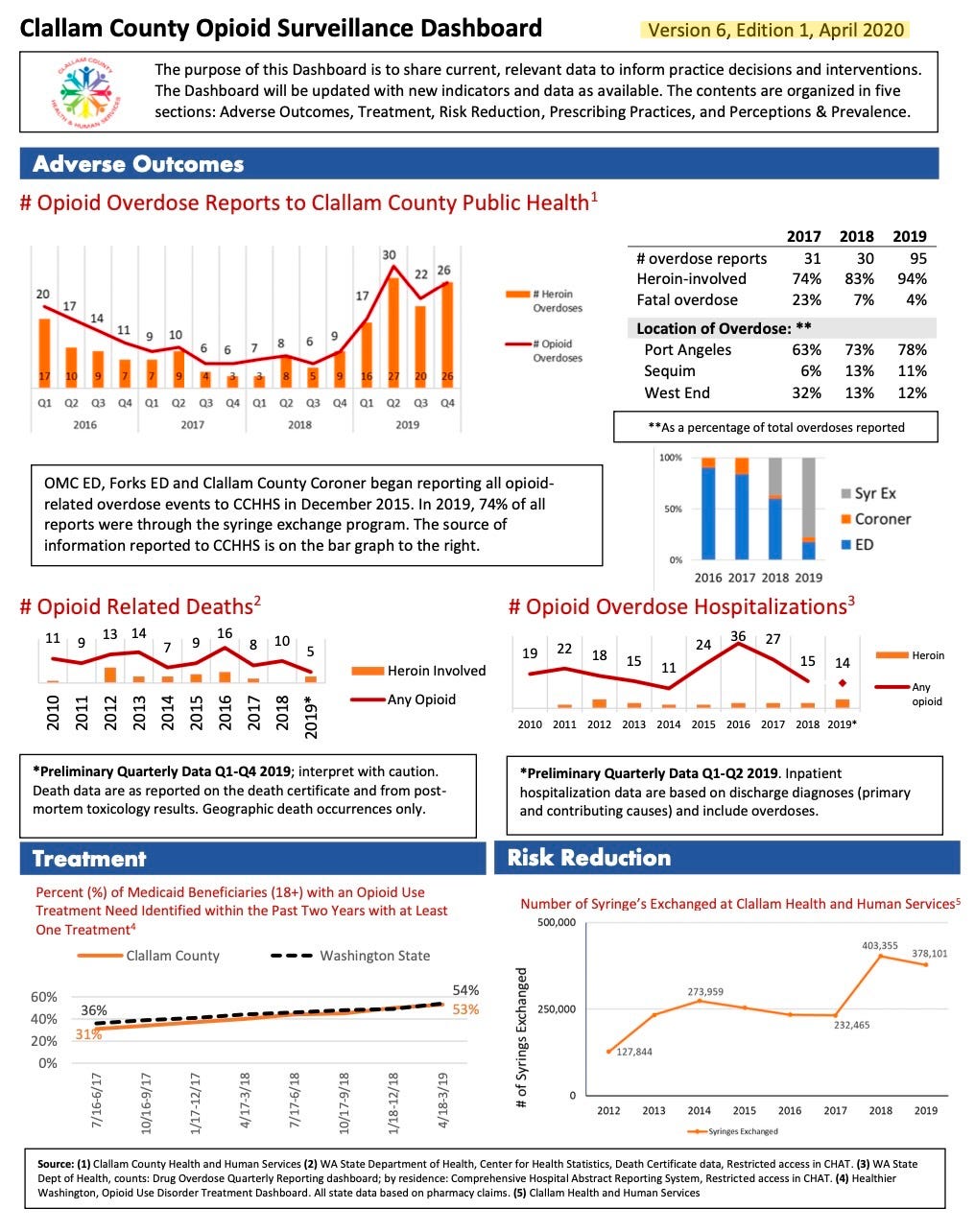

However, HHS was already responsible for reporting overdose trends. In fact, they maintained a public Opioid Surveillance Dashboard until 2020, but discontinued it just as overdose deaths began to rise sharply.

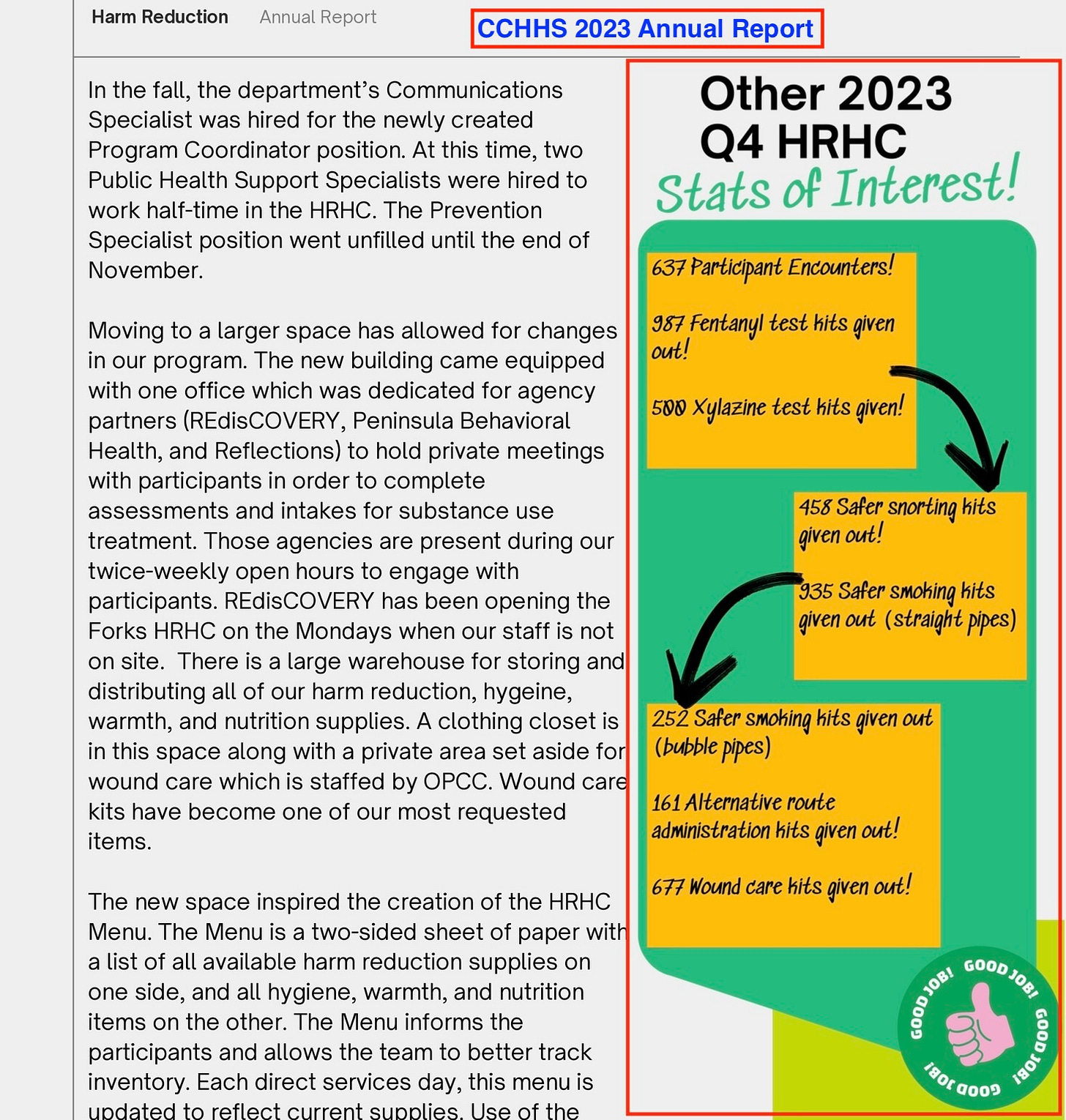

Instead of continuing to report transparent outcomes to the public, HHS has changed its metrics to now count:

Number of encounters

Test strips distributed

Safer-use kits handed out

And “alternative route” kits delivered

None of this data measures whether harm reduction works — it only shows whether county employees are keeping busy handing out harm reduction supplies.

So why the sudden urgency to “study” the gaps? One reason: Grant funding is drying up.

Vote of No Confidence

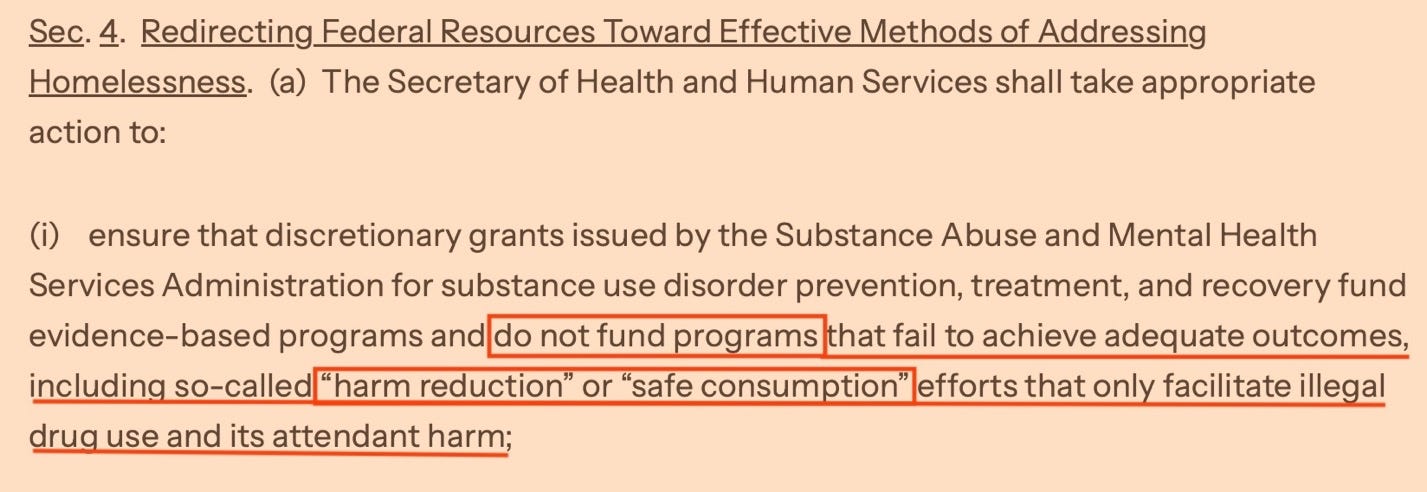

Federal agencies have recognized the long-term failure of harm reduction to reduce drug deaths. In July 2025, a sweeping federal order prohibited the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) from issuing grants to programs that “fail to achieve adequate outcomes,” explicitly targeting “harm reduction” and “safe consumption” programs.

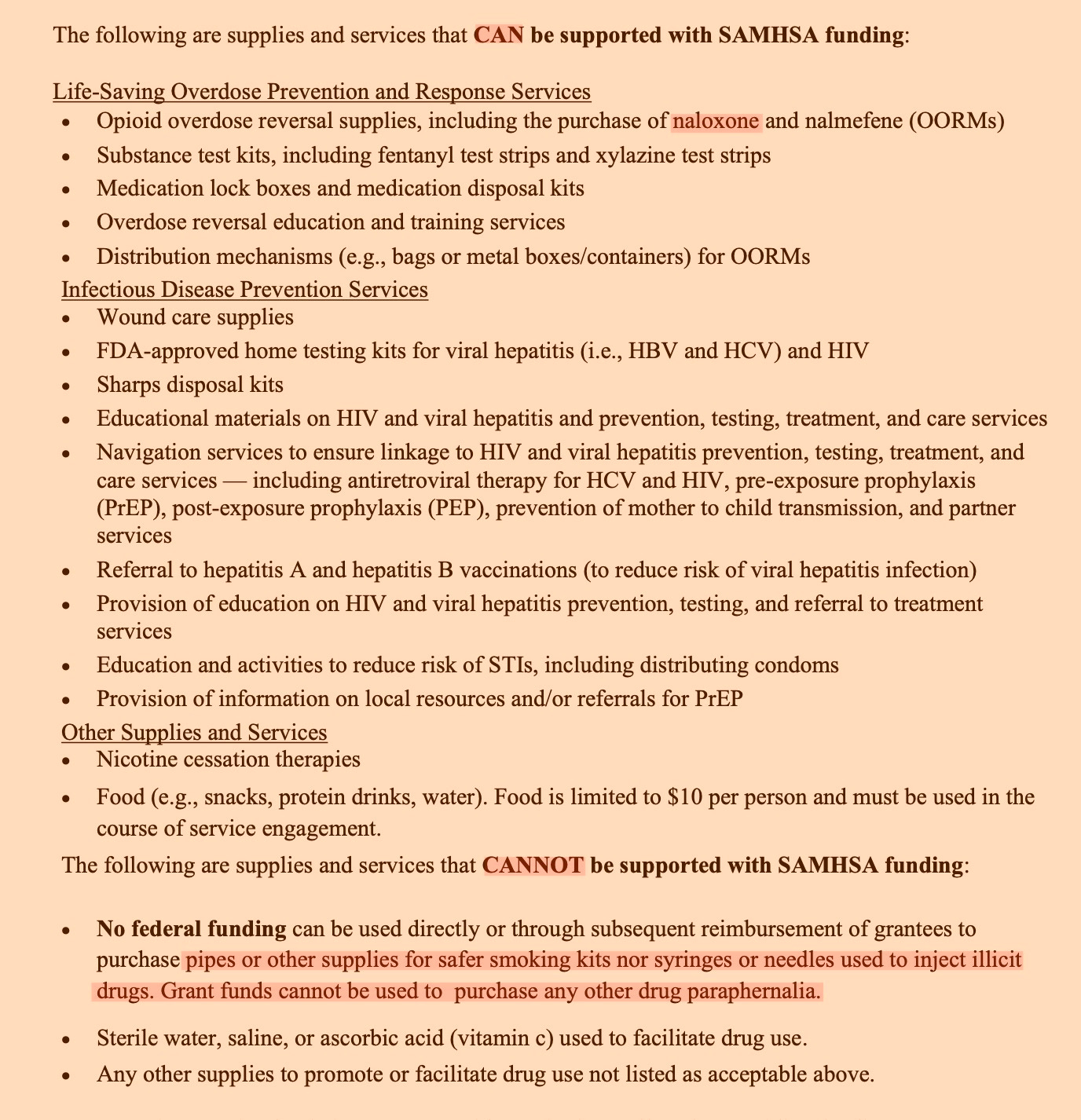

A clarifying letter issued on July 29th confirmed that funding would continue for life-saving overdose reversal (like Naloxone) and infection prevention — but not for supplies that facilitate drug use.

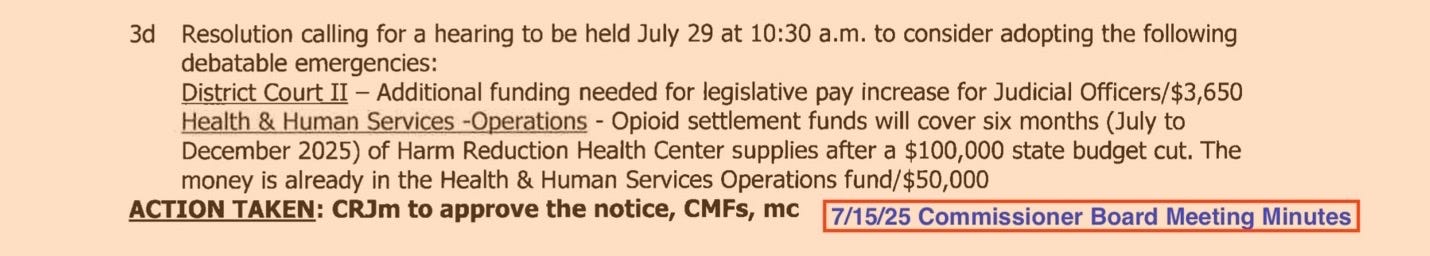

The impact was immediate - the County’s Harm Reduction Health Center (HRHC) lost $100,000 per year in reimbursable grant support starting July 2025.

Instead of downsizing, adapting, or reevaluating strategy, CCHHS appealed to the commissioners to backfill the loss with opioid settlement funds — money that is legally allowed for treatment, prevention, housing, and recovery, not just drug-use supplies.

The commissioners agreed to provide $50,000 for July–December 2025 and recently signaled another $50,000 for January–June 2026.

Clallam County continues to promote harm reduction and fund research to validate failed strategies while refusing to examine what actually works.

Expanding Harm

Clallam County leaders often describe grants as “free money” while expanding programs and payrolls. But when the grants disappear, the staff and programs remain — and taxpayers are forced to pick up the tab.

This pattern is common:

Earlier this year, the Clallam Conservation District warned of shrinking grants and reduced county funding — yet it continued expanding its payroll. The commissioners responded not by demanding accountability, but by imposing a new $5 parcel fee on every property owner, creating another $2 million tax burden for residents over the next decade.

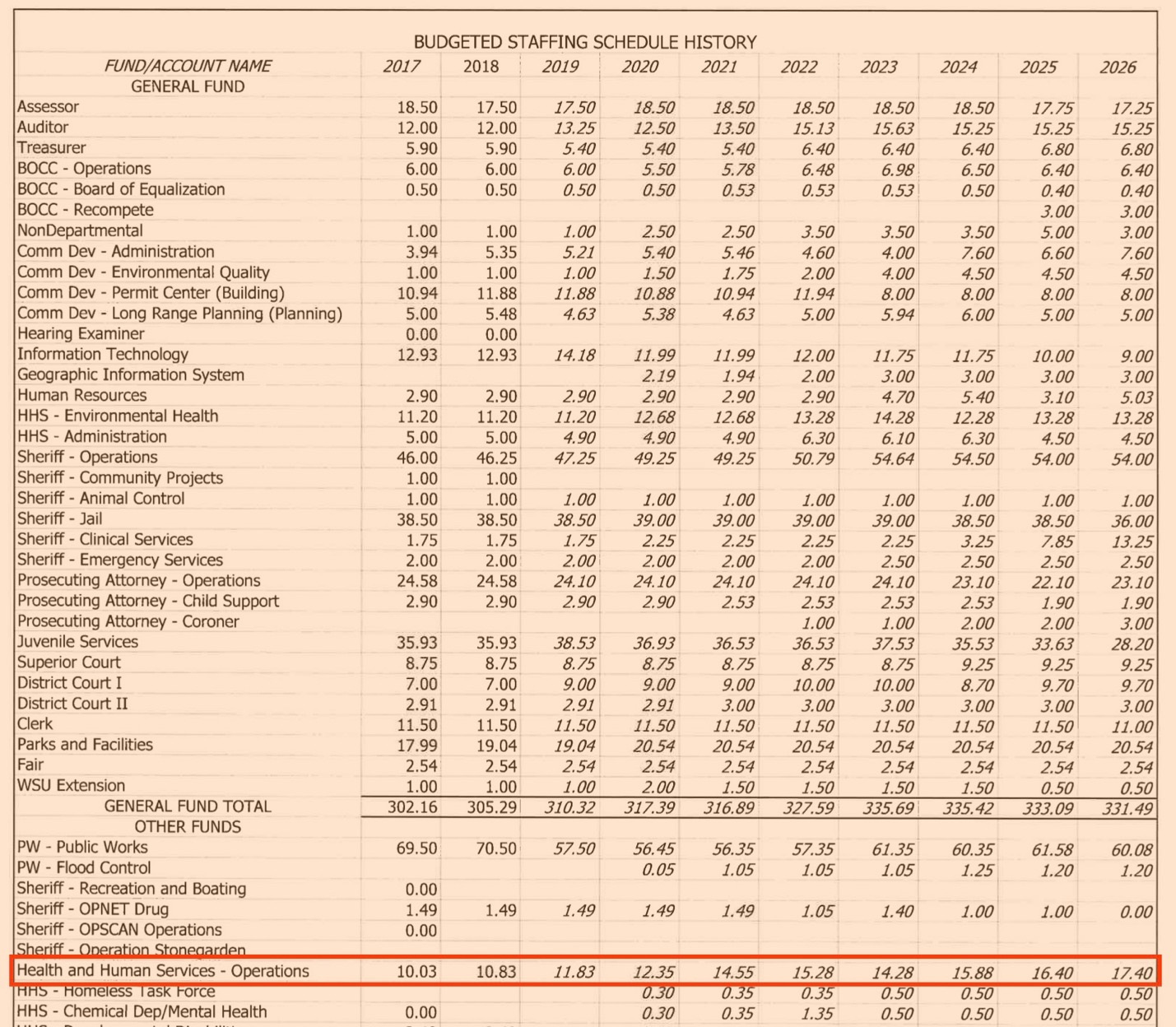

Health and Human Services has grown its staff by 74% since 2017 and added yet another full-time employee for 2026, despite losing grant support for core services.

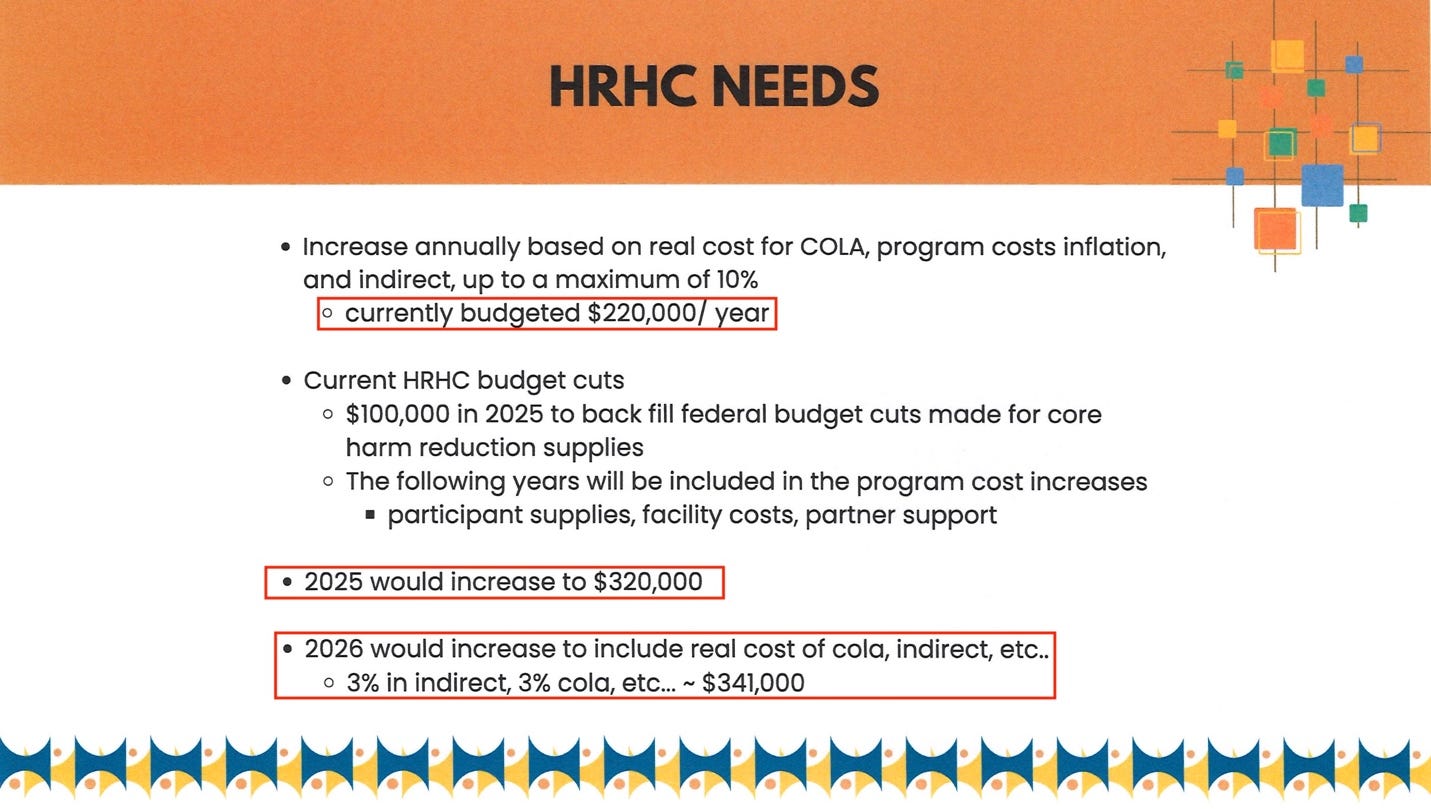

Harm reduction is following the same trend. During the June 17 Clallam County Board of Health meeting, HHS Deputy Director Jennifer Oppelt outlined the Harm Reduction Health Center’s expanding “needs.”

HRHC’s budget is slated to increase by an additional 6.6% in 2026 - attributed to “real” cost-of-living wage adjustments – even while federal grants disappear.

Harm reduction has expanded for nearly a decade, but outcomes have worsened.

Attribution Error

An attribution error occurs when the wrong cause is credited for an outcome, like assuming someone cut you off in traffic because they’re rude, when they were actually rushing to the hospital.

The commissioners, Health and Human Services, and the County’s Board of Health now appear to be making this mistake.

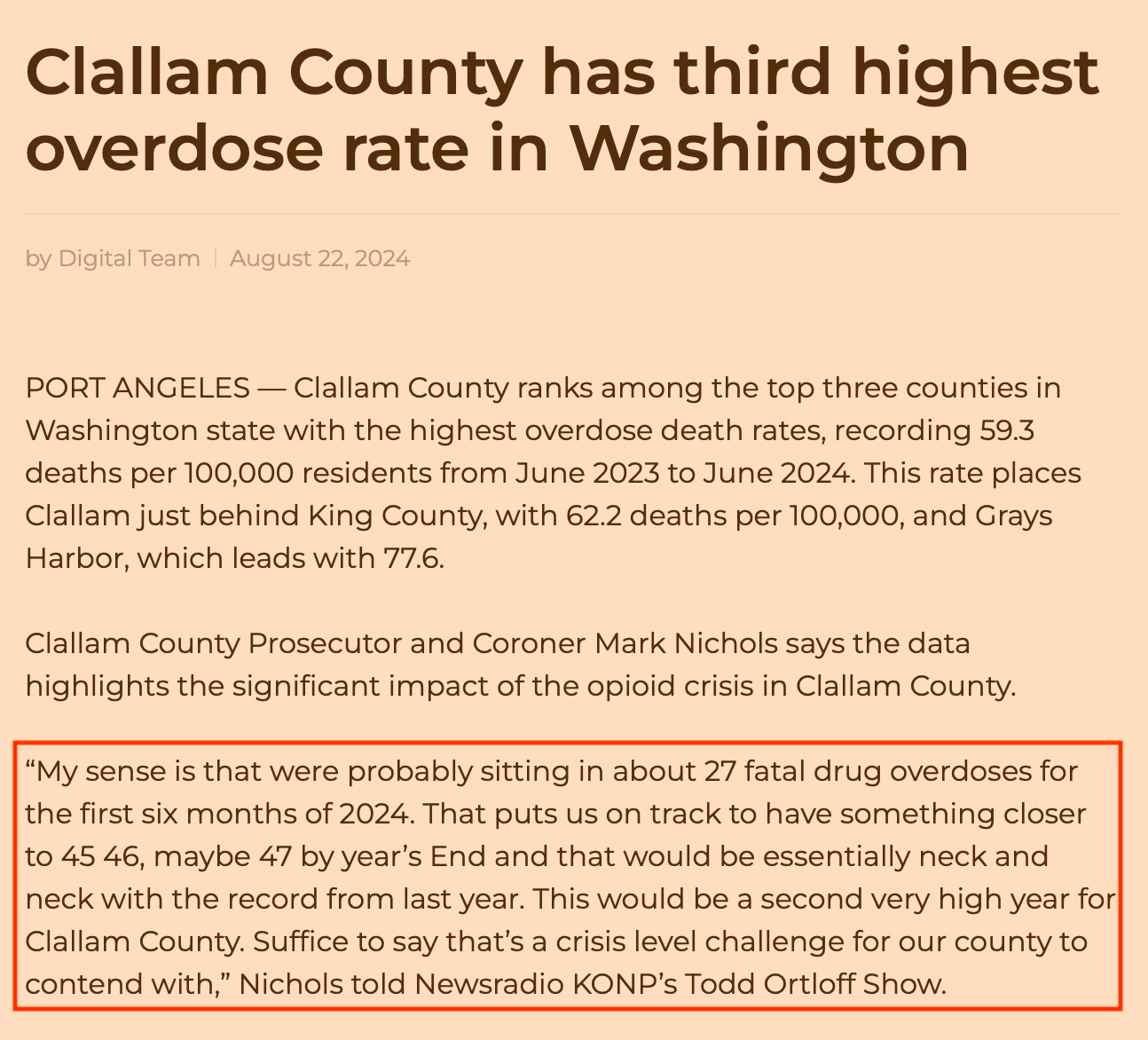

In August 2024, Prosecutor/Coroner Mark Nichols predicted on KONP that 2024 would break overdose-death records.

But instead, Clallam County saw an unexpected drop in overdose deaths in the latter half of the year — ending with 33, far below expectations. In a phone conversation, Deputy Coroner Rebecca Shankles expressed her surprise at the drop in overdose deaths but could not offer an explanation. She noted that the downward trend has continued into 2025.

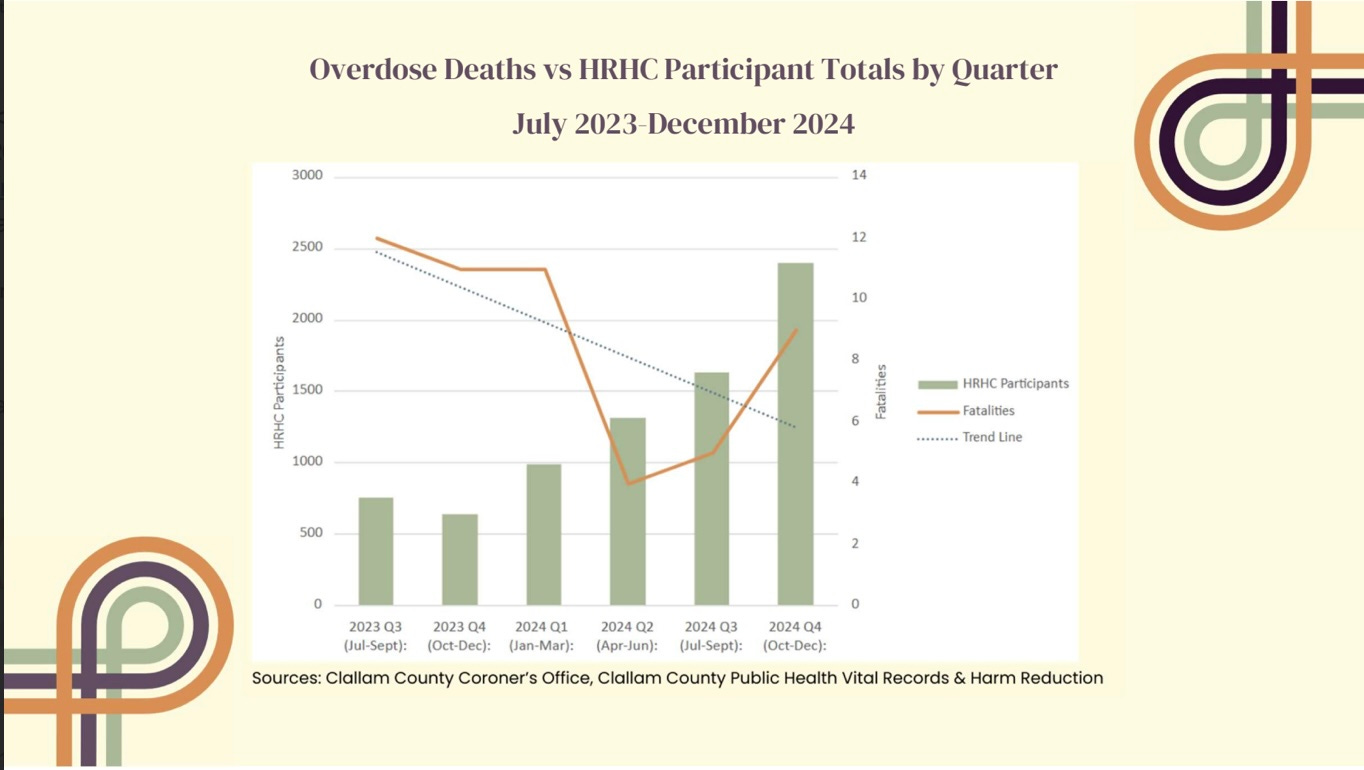

HHS Deputy Director Oppelt and Commissioner Ozias were quick to credit harm reduction, with Oppelt cherry picking a narrow 18-month dip in the data and holding it up as proof that the strategy works.

Commissioner Ozias echoed the claim in a Sequim Gazette article, pointing to increased HRHC visits as evidence of success.

“We see a clear trend line correlating the number of visits to the Harm Reduction Health Center, which has been increasing each quarter since it opened, and the reduction in overdose deaths.”

But the broader trend contradicts them entirely:

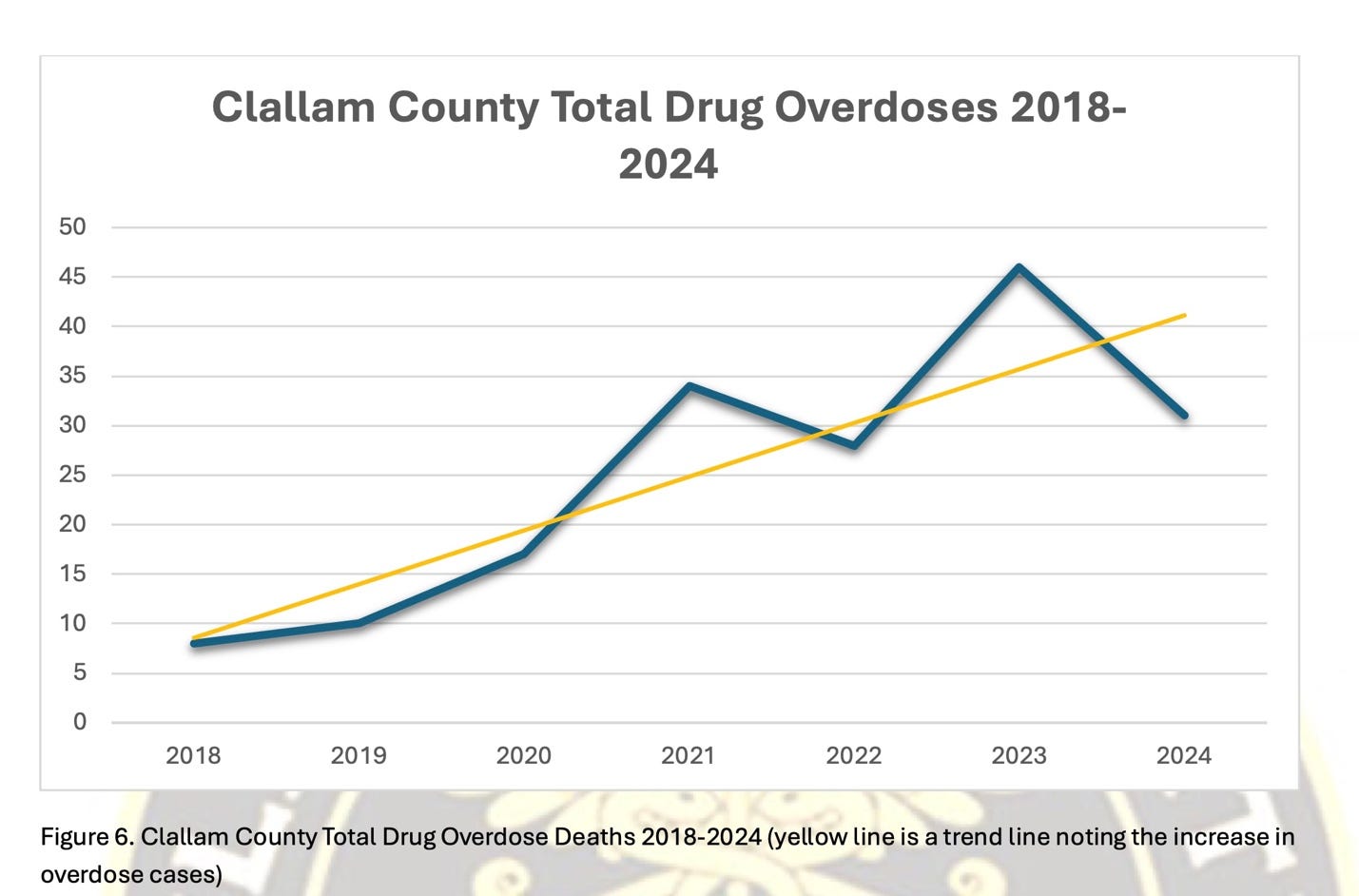

Overdose deaths in Clallam have increased by over 400% since 2018.

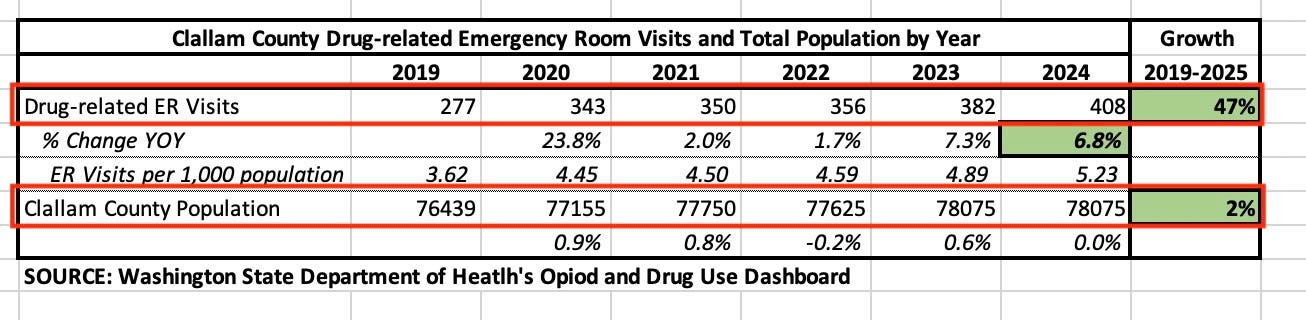

Opioid-related ER visits are up 47% since 2019, even though the population grew only 2%.

ER visits rose another 7% in 2024.

HRHC monthly encounters jumped from 212 (2023) to 508 (2024) to 974 (2025), according to annual reports and statements by Ms. Oppelt.

As harm reduction has expanded, so have drug activity, overdose deaths, and drug-related ER visits.

If these programs were truly effective, long-term indicators wouldn’t be spiraling in the wrong direction.

What Changed: Operation Shielding Hope

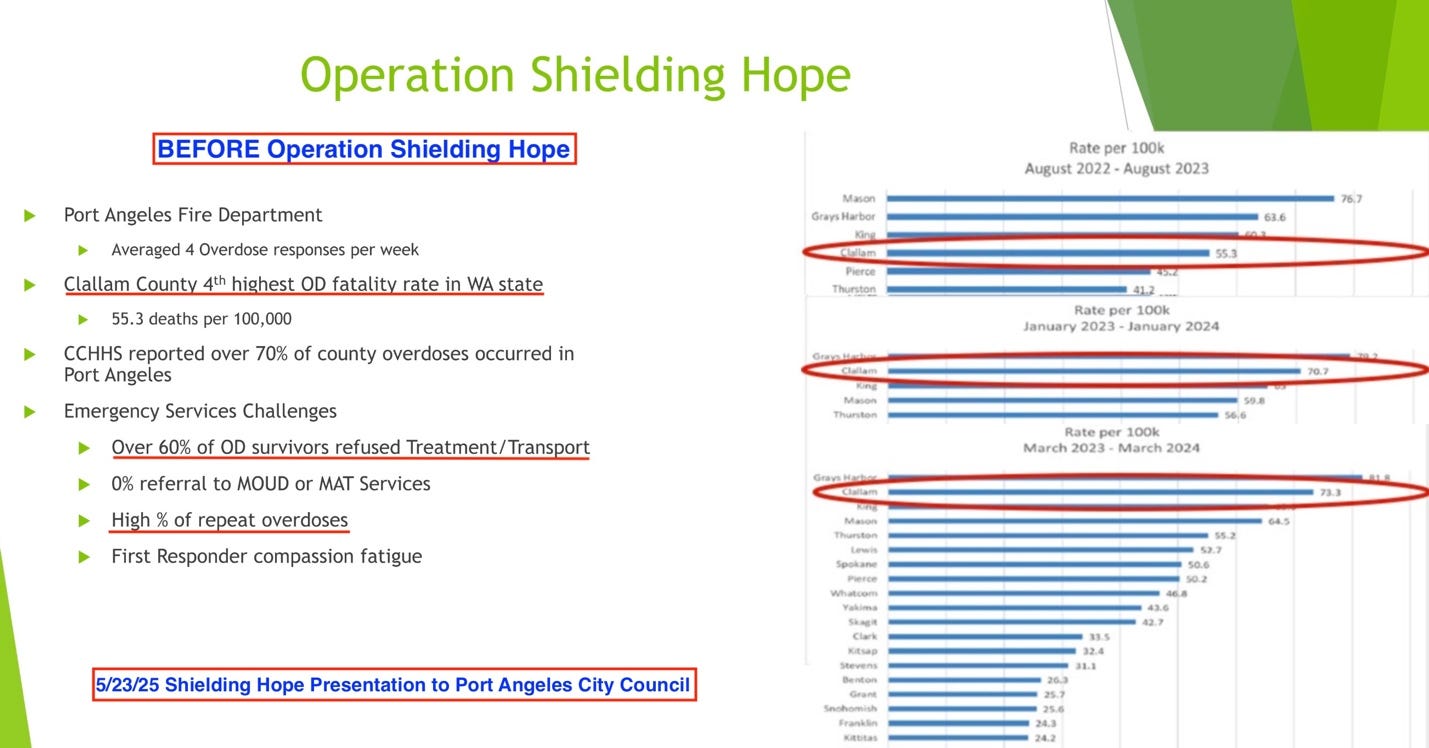

The timing of the decline in overdose deaths aligns not with harm reduction expansion—but with the rollout of Operation Shielding Hope, which the Port Angeles Fire Department launched in early 2024.

The program began in March 2024 and received a $350,000 grant from the University of Washington in June.

Shielding Hope’s model is fundamentally different from the harm-reduction strategies the county has relied on for the past decade. Rather than distributing supplies or facilitating “safer” drug use, the program uses the critical moment after an overdose—the second chance at life—to guide people toward real treatment and a path out of addiction.

Community paramedics respond immediately after overdoses, stabilize patients, and build trust.

Before this program, 60% of overdose survivors refused help and walked away.

Police and fire officials believed overdose survivors were refusing help because extremely high Narcan doses triggered acute withdrawal, sending them to use again almost immediately. To break this cycle, they created a response team able to administer buprenorphine, stabilize patients on scene, and—most importantly—use immediate paramedic engagement and warm handoffs to build trust.

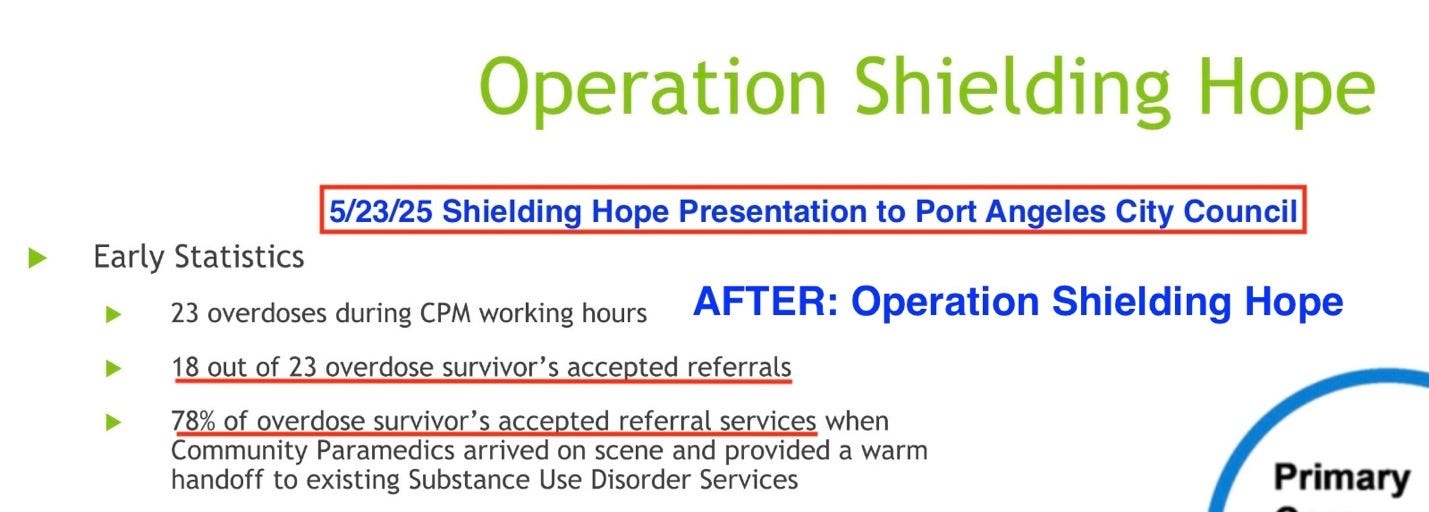

More than a year after Shielding Hope launched, staff reported that buprenorphine was used only sparingly; the real driver of increased treatment referrals was the on-scene relationship-building.

Under Shielding Hope:

78% of overdose survivors engaged with services.

Without paramedic intervention, only 3% did.

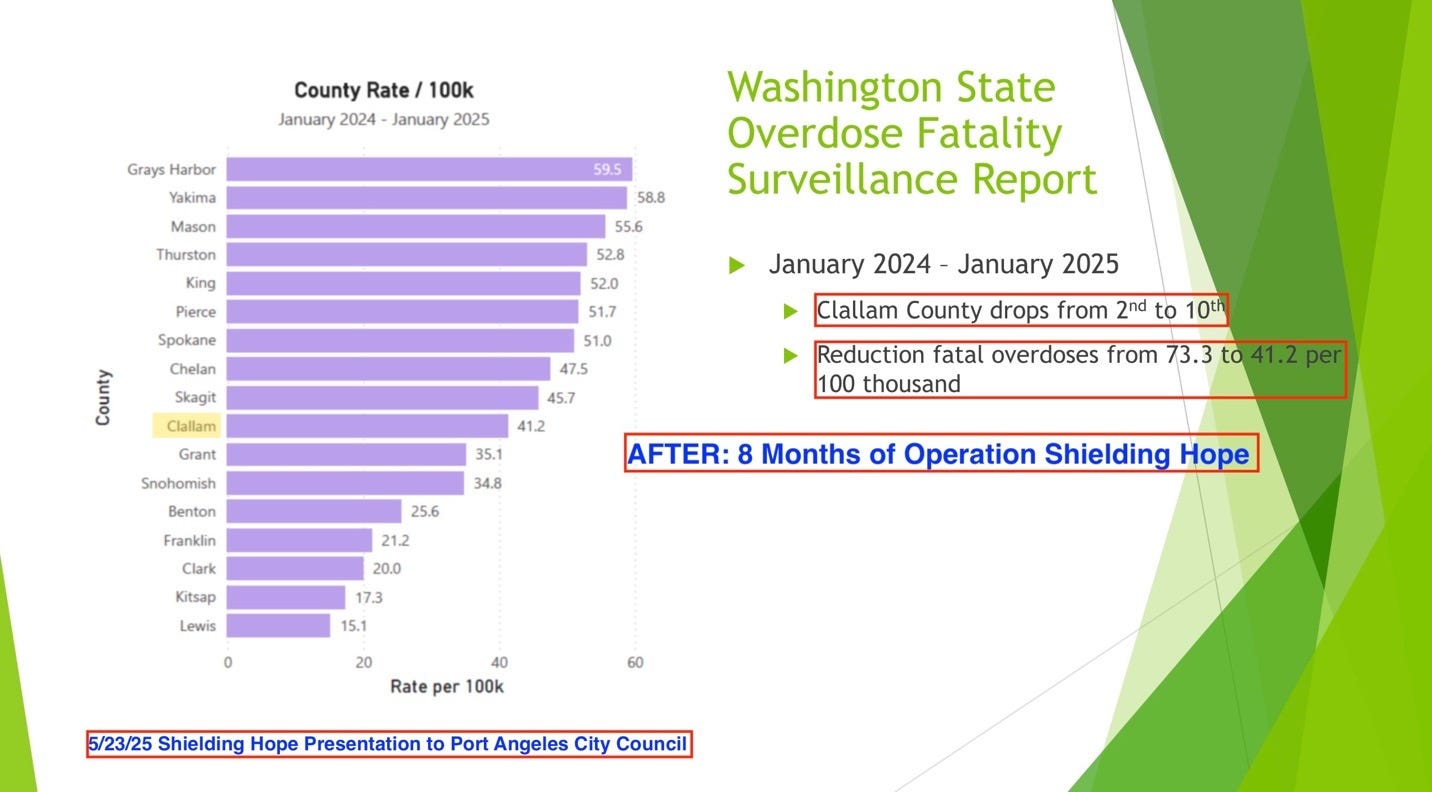

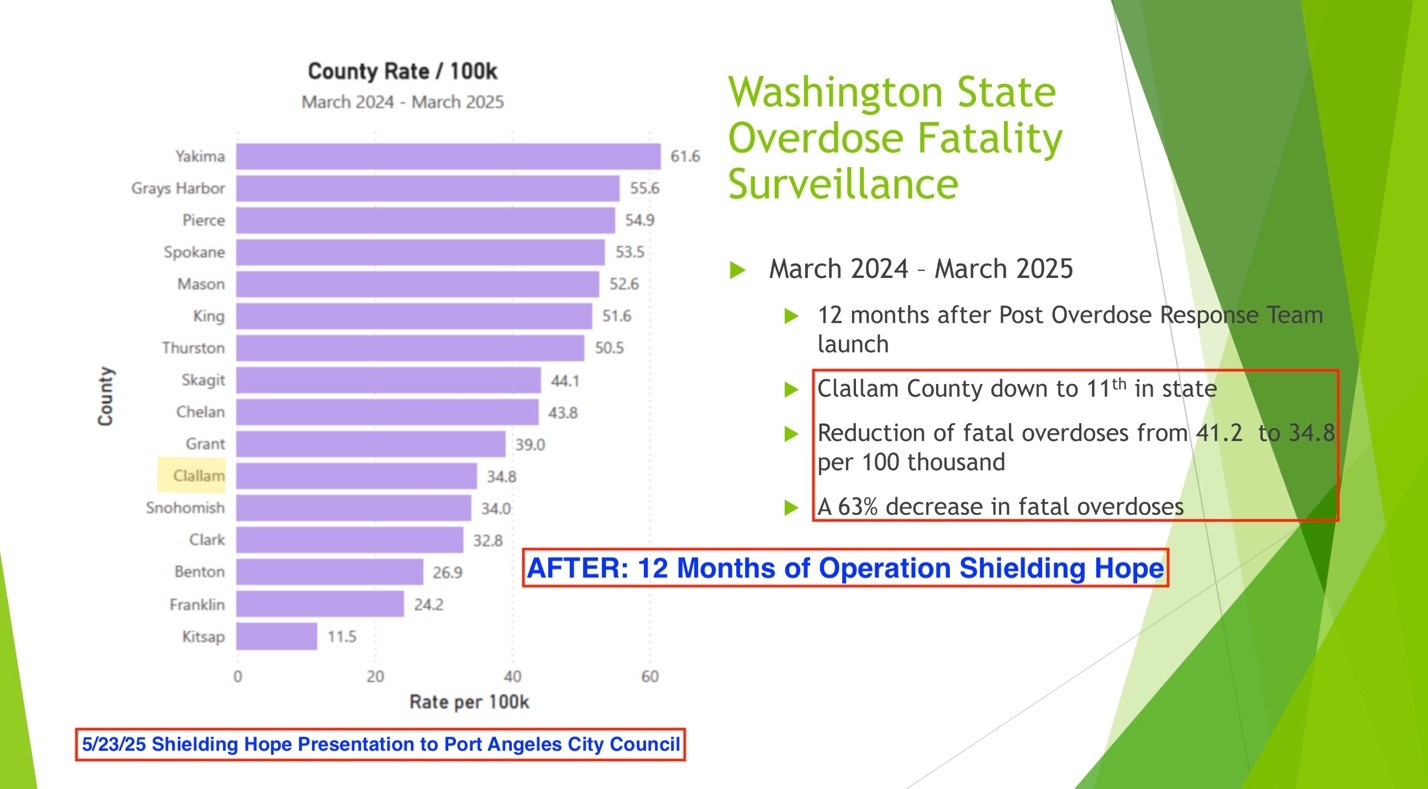

In May 2025, Fire Chief Derrell Sharp reported to the Port Angeles City Council that overdose deaths per 100,000 had dropped from 73.3 to 41.2, then to 34.8

Clallam fell from the 2nd-highest overdose rate in Washington to the 10th, then 11th.

HHS itself attributes 70% of county overdoses to Port Angeles — exactly where Shielding Hope operates.

The correlation is strong.

The timing is aligned.

The mechanism is logical.

And the results match the intervention.

Shielding Hope is saving lives. Harm reduction is not.

Voices of Experience

When Clallam County Watchdog interviewed Chelsea Jones — a Port Townsend mother who escaped addiction and years of living in the woods — her message was unmistakable:

Harm reduction kept her trapped.

Door delivery of drug-use supplies made it easier to continue using.

Only treatment, accountability, and someone she trusted breaking through at her lowest point saved her.

Chelsea’s lived experience aligns with Shielding Hope’s success and contradicts a decade of harm reduction messaging.

The Harm Reduction Health Center Hijack

By funding their own “gaps study” with opioid-settlement dollars, Health and Human Services and the Board of Health appear poised to credit their harm reduction programs for the decline in overdose deaths.

But the data, timing, and success of Operation Shielding Hope, and the lived experiences of survivors like Chelsea, tell us otherwise.

Clallam County must stop miscrediting success — and start funding what works.

Real Solutions

Chelsea was clear about what actually works.

1. Prioritize treatment, not facilitation

Opioid-settlement funds should support treatment pathways—not drug-use supplies.

That means expanding front-line programs like Operation Shielding Hope, increasing access to treatment assessments, and strengthening local detox and recovery options.

These interventions save lives; harm reduction does not.

2. Reduce the cash that fuels addiction

Chelsea explained that every dollar she received while “flying a sign” went straight to drugs.

Not groceries.

Not essentials.

Drugs.

Discouraging panhandling at high-traffic locations cuts off easy money and removes the financial incentive that attracts dealers and perpetuates use.

3. Enforce trespass and no-camping ordinances

If long-term camping in public spaces is no longer an option, Clallam County will not attract out-of-town homeless populations seeking permissive environments. Enforcing existing rules also ensures safer, more stable options for local residents who genuinely need help.

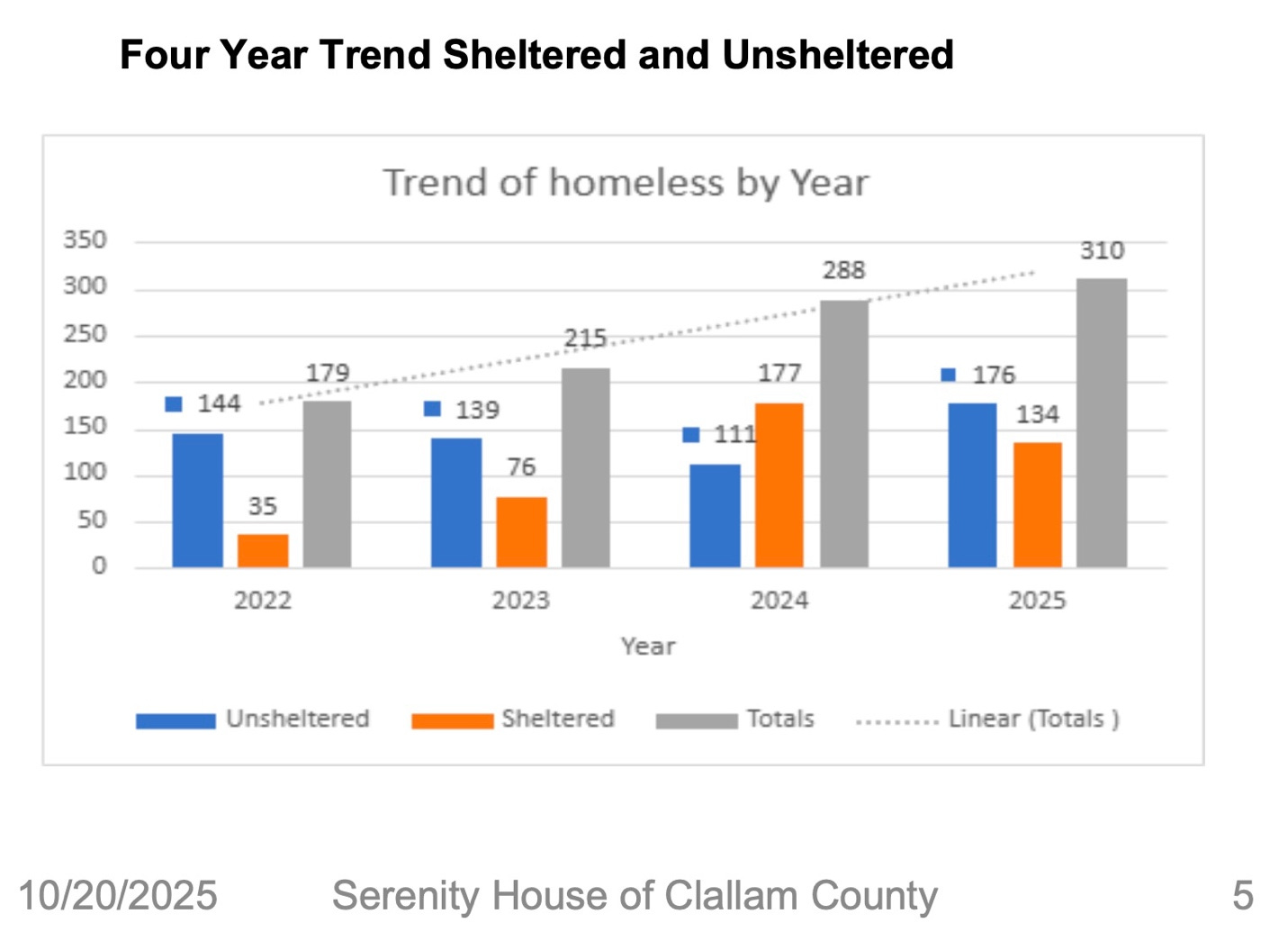

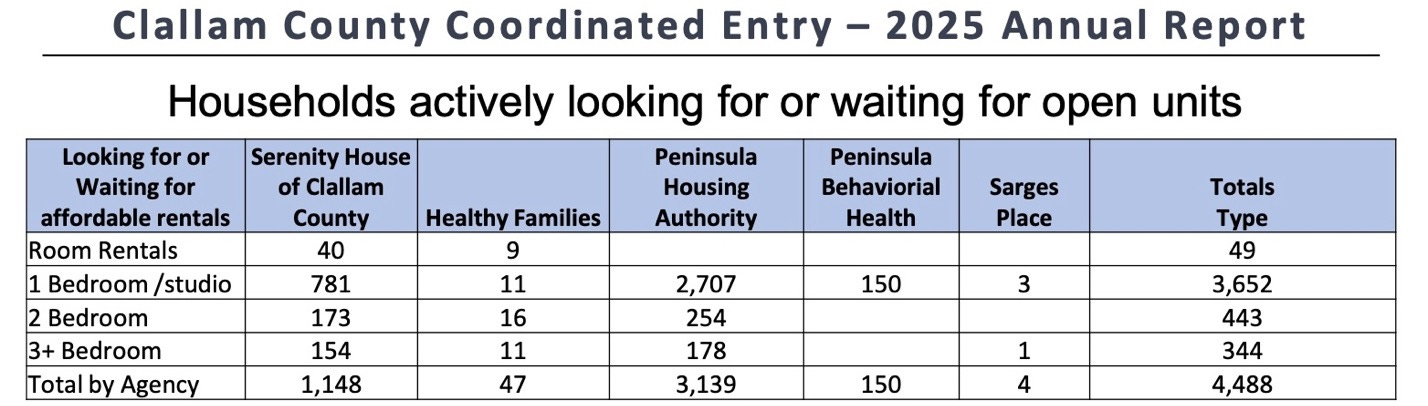

The 2025 Coordinated Entry Report counted 176 unsheltered individuals in the county.

Yet that same report lists 4,488 households on the waiting list for housing assistance—26 times the Point-In-Time (PIT) count. And 81% of those households need a 1-bedroom or studio unit.

These numbers strongly suggest that Clallam County’s housing resources are not prioritized for its own residents' needs.

What you can do

Write the commissioners - voice your opinion about the $341,000 harm reduction budget and where those funds could better serve those suffering from addiction.

All three county commissioners can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov

Last week, Jake Seegers asked readers what is most effective for long-term recovery. Of 198 votes:

84% said, “Accountability”

13% said, “Treatment”

2% said, “Housing”

2% said, “Harm reduciton”

Editor’s Note: CC Watchdog editor Jeff Tozzer also serves as campaign manager for Jake Seegers in his run for Clallam County Commissioner, District 3. Learn more at www.JakeSeegers.com