The county commissioners’ four guiding mission statements promise achievable goals, yet long-time residents say those promises ring hollow: unanswered complaints, stalled code enforcement, delayed ordinances, and a web of outside committee obligations that raise real questions about priorities and equity.

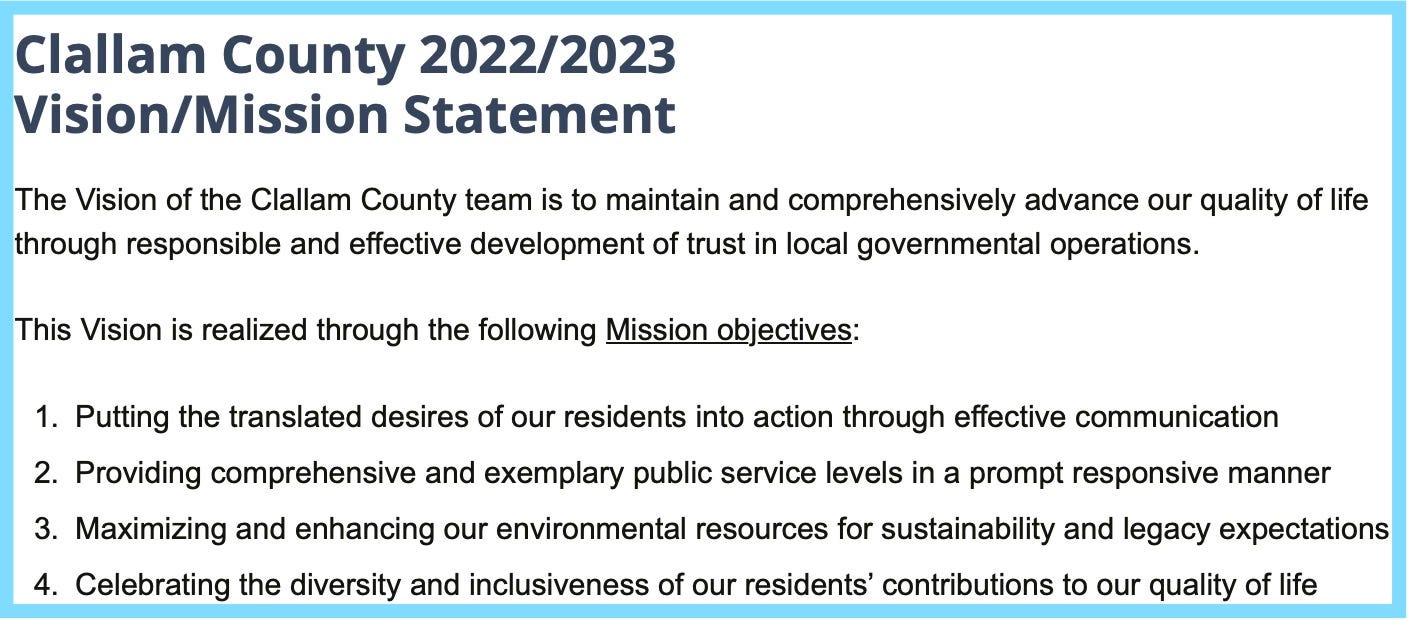

Clallam County’s elected leaders publish a set of clear, admirable mission objectives. They commit to translating residents’ priorities into action through effective communication, providing prompt and exemplary service, protecting environmental resources, and celebrating diversity and inclusion. Those goals set a high bar — and that’s the point. Equity isn’t a slogan here; it’s supposed to be a framework for who gets heard, who gets helped, and how fairly public resources are applied.

But for many residents, the lived experience looks very different.

Instead of swift responses and coordinated service, some constituents describe a county government that is slow to act, inconsistent in enforcement, and more attentive to gatherings, galas, and outside boards than to the backyards and beaches of taxpayers who elected them.

That’s an equity problem: when access, safety, and property rights are handled differently depending on who’s affected, the county’s stated values become empty words.

Time spent — and time taken away

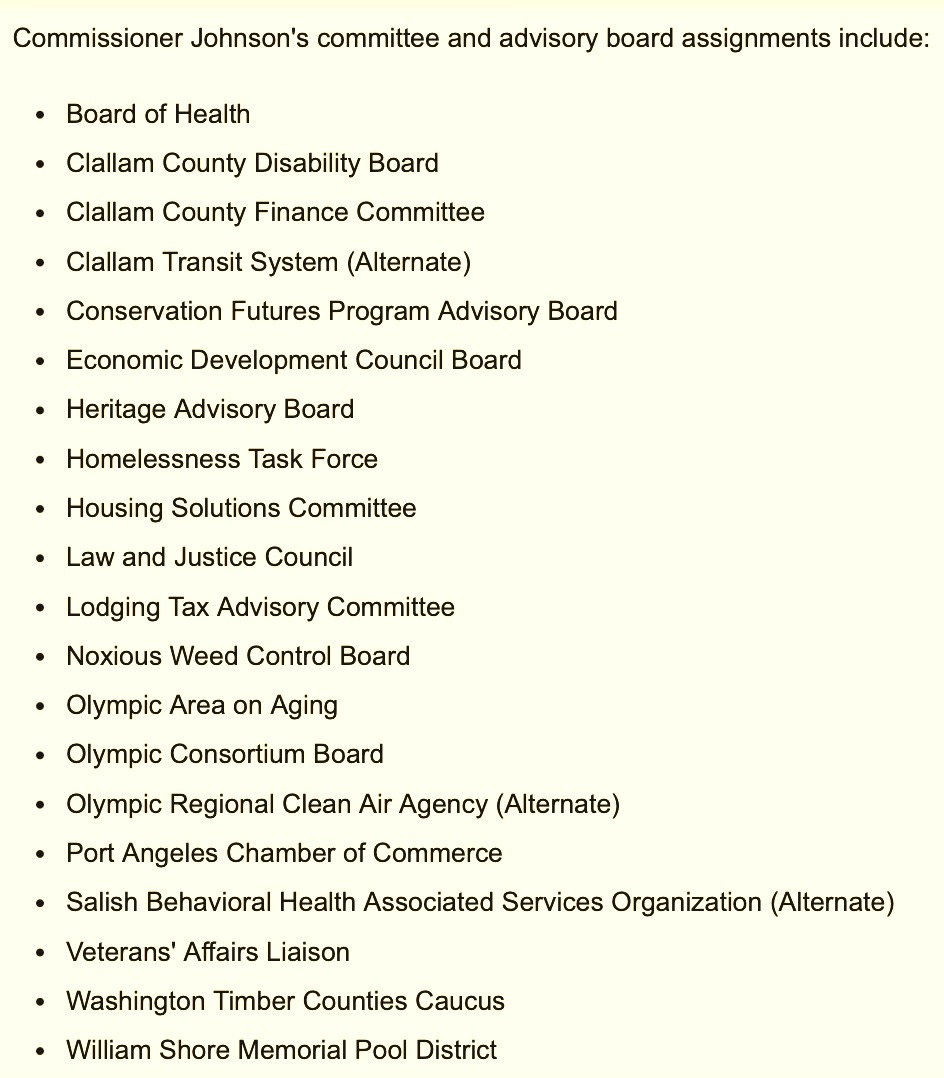

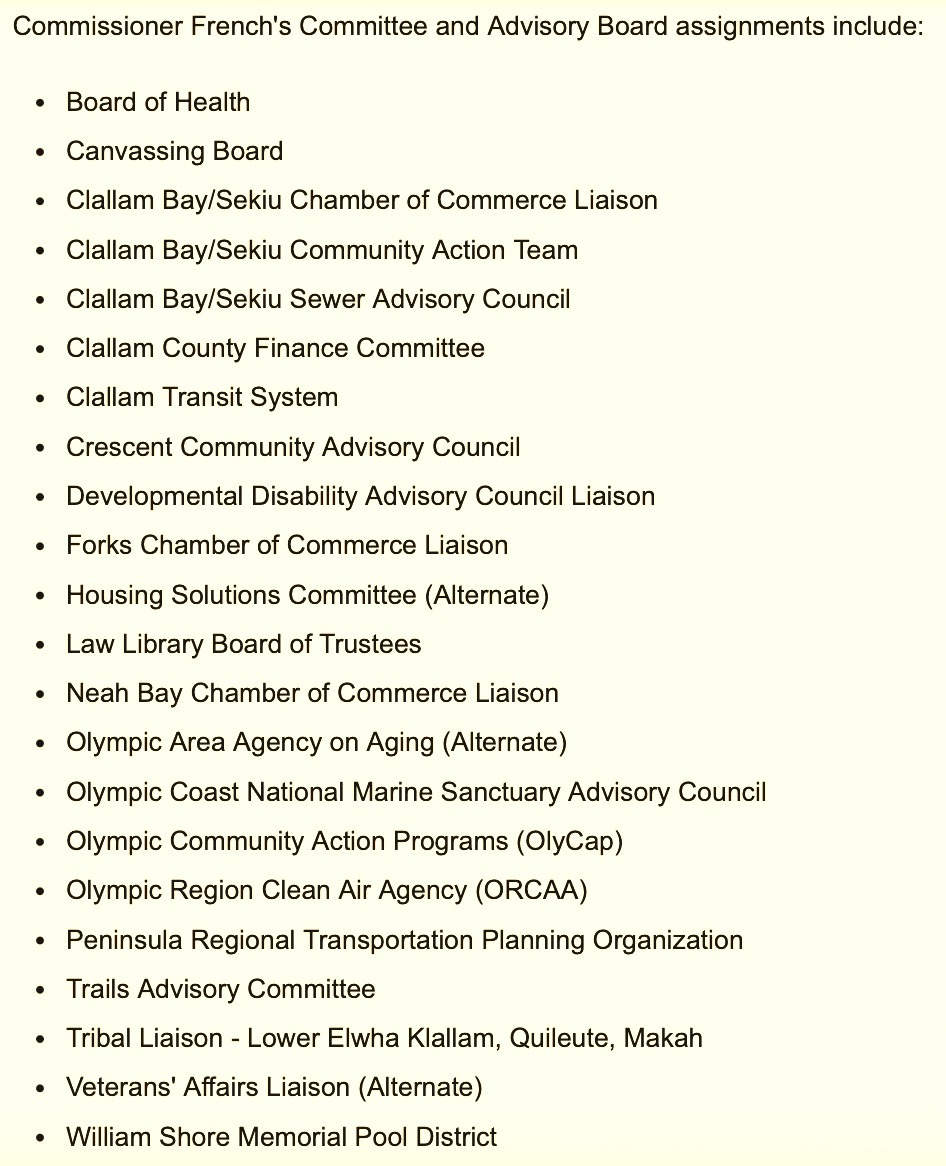

There is clear value in commissioners serving on local boards and committees: it can help align county priorities with regional partners and bring influential perspectives to the table. But a close look at the committee lists for Commissioners Mark Ozias, Randy Johnson, and Mike French shows an intense web of assignments — everything from behavioral health and marine resources to chambers of commerce, transportation planning, and tribal liaisons. That’s a lot of meetings, travel, and advocacy outside the bounds of their core role.

Residents are left asking: Does the time and influence commissioners invest in external organizations come at the expense of the prompt, responsive governance their mission promises? When code complaints sit unresolved for months or years, when noise ordinances remain unupdated for nearly a decade, and when neighbors say they feel ignored by the very people paid to represent them, equity demands an answer.

A resident’s chronicle: the cost of being ignored

District 2 resident Ed Telenick’s emails to his elected leaders are a long, painful chronicle of a family exhausted by bureaucratic failure.

Despite repeated appeals for help, Ed Telenick and his family saw little meaningful action from county staff or commissioners. Inspections produced misleading reports, cases were mishandled or closed without resolution, and poor coordination between departments left serious issues like failed septic systems and possible watershed contamination unaddressed. The result was significant personal and financial harm — including a $50,000 expense to protect their well and declining property value — compounded by noise, illegal RVs, theft, and harassment that law enforcement failed to curb. After years of frustration, stress, and neglect, the couple who once volunteered and donated widely now plan to leave Clallam County, saying they no longer trust local government to protect property rights, public health, or equitable treatment.

Ed’s letter is not a mere complaint — it’s a catalog of procedural breakdowns and real-world harms that raise the question: if the county’s processes create winners and losers, where does equity fit?

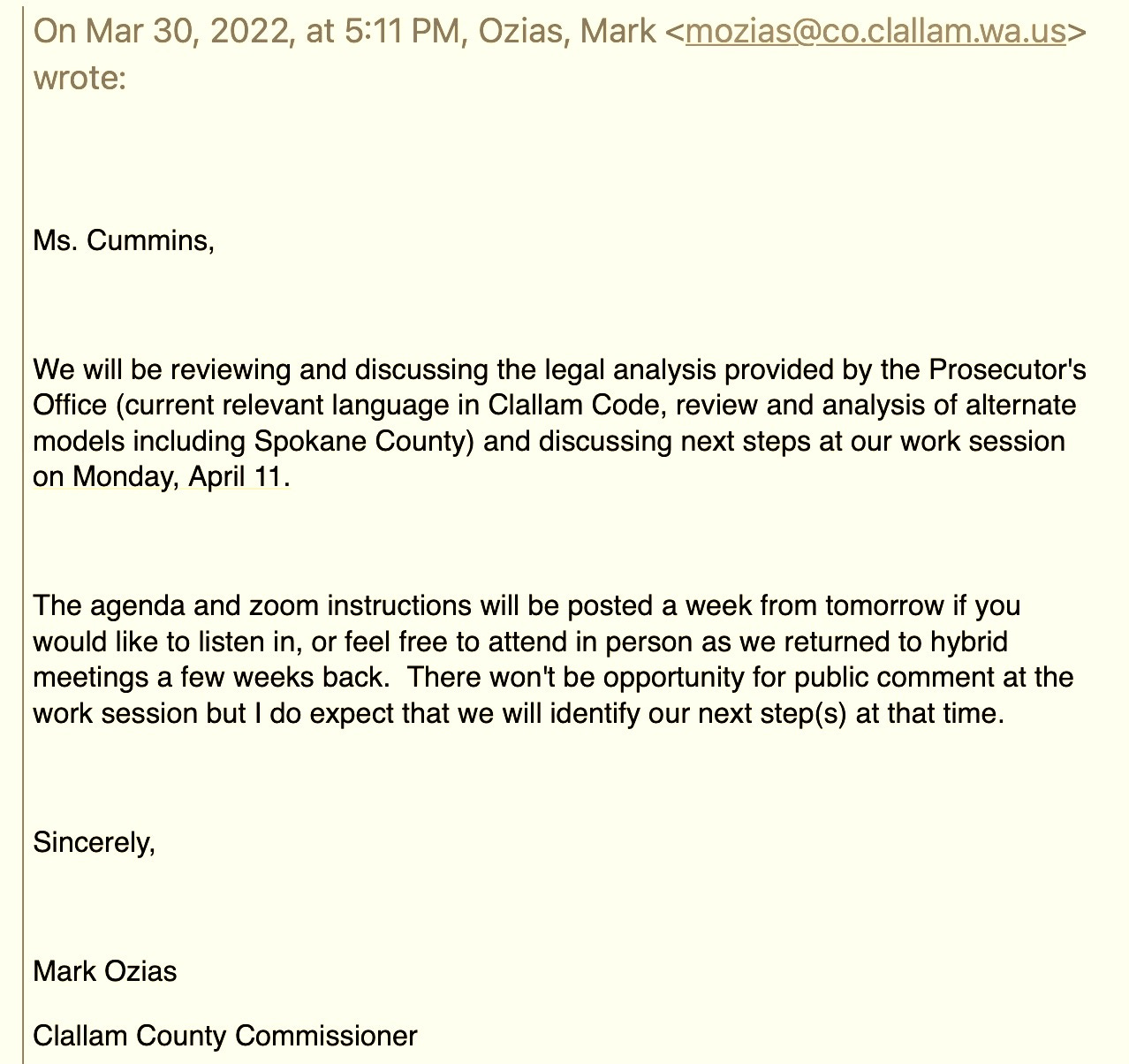

Promises deferred: noise, code, and the slow wheel of change

Consider another long-running story: Kärin Cummins of Dungeness sought relief from a neighbor’s incessant generator noise that began in 2017. She reached out repeatedly — Department of Community Development, the Sheriff, county administrators, the civil deputy prosecutor — and was given essentially the same response: “it’s in the queue.” No meaningful action followed, and years later Cummins is still waiting for an update to the county noise ordinance to encompass generators. That’s not only poor customer service; it’s a gap in policy that unfairly burdens people trying to live in peace.

Nearly 600 residents who depend on 3 Crabs Road for access to their homes are still waiting for action, especially after the Marine Resources Committee urged the County Commissioners to address flooding by evicting residents from their property and removing the road.

Five months have passed since that recommendation, and the Commissioners haven’t even acknowledged the letter. In the meantime, neighbors face another winter of rising water — flooding they say was made worse by the County’s Meadowbrook Creek restoration with the Jamestown Tribe. Should families invest in their homes or brace for displacement? Will the County step up with emergency access plans, or again leave residents to shoulder the risk alone? For now, the issue sits ignored, while Commissioners prioritize proclamations on diaper awareness and food waste education.

Special interests or the public interest?

There’s a troubling optics problem when commissioners champion causes or attend events that appear to favor certain groups while persistent constituent problems remain unresolved. Examples from the record:

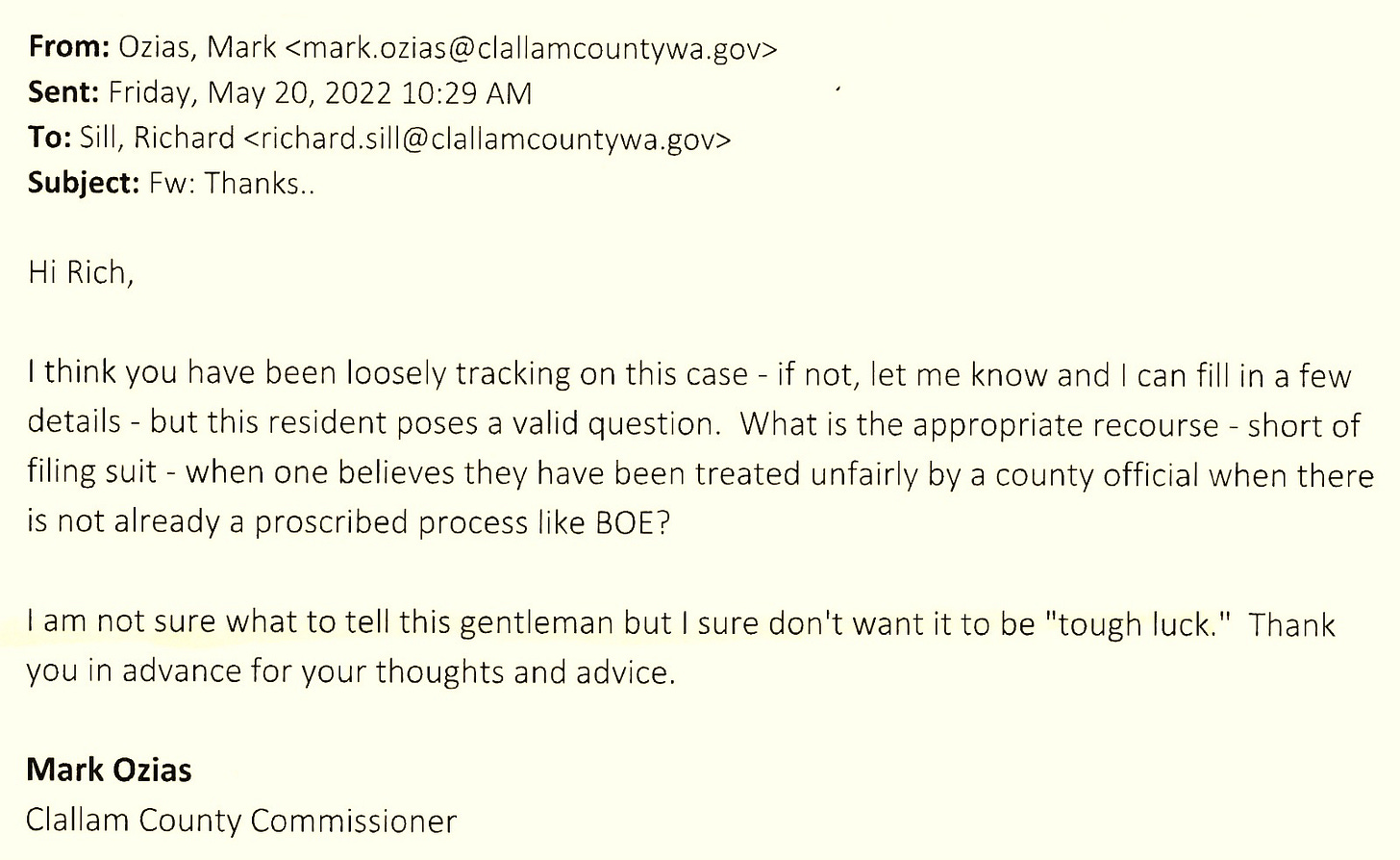

Commissioner Ozias authored a four-page objection to reopening a gravel pit near his home, citing noise and sleep disruption concerns — a fight he had the bandwidth to pursue. Yet other residents report years of sleep disruption from generators without comparable county action.

Commissioner French made a presentation lobbying for a culture-access tax that benefits arts organizations; constituents wonder who benefits when funding priorities are set.

Ozias, the Tribe, and the DRMT

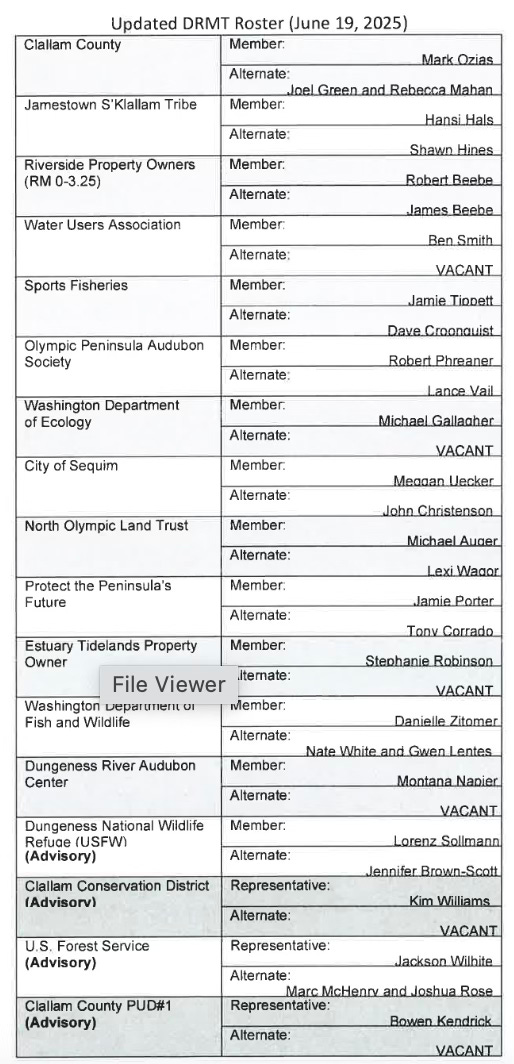

Commissioner Mark Ozias has added yet another role to his long list of outside commitments: he now sits on the Dungeness River Management Team (DRMT) — the joint county/Jamestown S’Klallam body that effectively manages everything related to water in the Sequim area.

On the tribal side, the representative is Jamestown’s Natural Resources Director Hansi Hals. She’s the same official who oversaw the early removal of the Dungeness River dike — a move that nearly caused a mass-casualty flood downstream. Hals also led the charge against the one cost-saving solution that would have kept Towne Road open and saved taxpayers an estimated $15 million: a temporary levee. Her justification? That it would infringe on tribal treaty rights and raise “equity and justice” concerns, even though it would have protected taxpayers and property owners.

For his part, Commissioner Ozias sided with the Jamestown Tribe and worked repeatedly to block the completion of Towne Road — at least ten separate attempts — whether by trying to defund it, proposing to turn it into a private driveway for allies, or converting it into an outdoor classroom for his top campaign donor. The question practically asks itself: when has Commissioner Ozias ever stood up to the Jamestown Tribe on behalf of the public?

From backing the Climate Commitment Act, to supporting the Blyn roundabout, to penning a letter of apology to the Tribe, to thwarting the reopening of Towne Road, his record shows a consistent pattern of deference.

Sequim’s motto is “Where Water is Wealth.” Today, DRMT manages that wealth — but with Commissioner Ozias and Hansi Hals steering the agenda, the scales are tilted. Residents should be asking: Who really controls the water, and do you have equal representation at the table?

Questioning those alignments isn’t anti-tribal; it’s pro-accountability. Equitable governance requires transparency about who is consulted, how trade-offs are weighed, and how competing values (treaty rights, environmental restoration, public safety, property rights) are reconciled — especially when decisions have immediate safety and property implications for residents.

A Call for Equity Through Accountability

County departments are out of sync, and residents fall through the cracks. If “effective communication” and “responsive service” are truly mission goals, then leaders must deliver timelines, accountability, and clear reporting so people know where their concerns stand.

Accountability isn’t partisan; it’s equity. But equity requires focus. Too many outside boards and committees mean commissioners are spread thin, distracted from the job voters elected and pay them to do. Restricting outside commitments ensures their first priority is Clallam County.

The stories of Ed Telenick and others aren’t just complaints — they are warnings. Equity means those signals can’t be ignored, and the public will keep demanding better until leadership delivers.

Hospital meeting tonight

Olympic Medical Center Board Meeting – Wed. Sept. 17th – 6:00 pm - The board meets in person in the Linkletter Hall in the basement of the hospital. There is also an option for virtual attendance. The agenda and virtual attendance instructions for this week’s meeting can be found HERE.