In this investigation, Jake Seegers exposes how Clallam County’s homelessness system has drifted from its mission and begun serving everyone except the people who live here. Despite millions in taxpayer funding, hundreds of empty shelter beds, and two decades of planning, NGOs continue to prioritize out-of-county applicants, bypass local needs, and defend policies that keep public land filled with trash, tents, and open drug use. From the safe-parking program with zero participants to the 4,488-person waiting list inflated by nationwide applicants, Seegers reveals a system designed for growth—not results. This is the story of how Clallam became the county of least resistance—and what can be done, right now, to turn it around.

Citizens are taxed. NGOs call the shots. Government promises fail. Local leaders continue to miss the obvious solutions.

In 2005, Washington passed House Bill 2163, requiring each county to adopt a homelessness plan funded by document-recording fees. That same year, Clallam County created its Homelessness Task Force (HTF) and adopted a plan with an ambitious mission: end homelessness in Clallam County.

But instead of managing the system itself, the county handed responsibility to a network of NGOs — with Serenity House of Clallam County taking the lead.

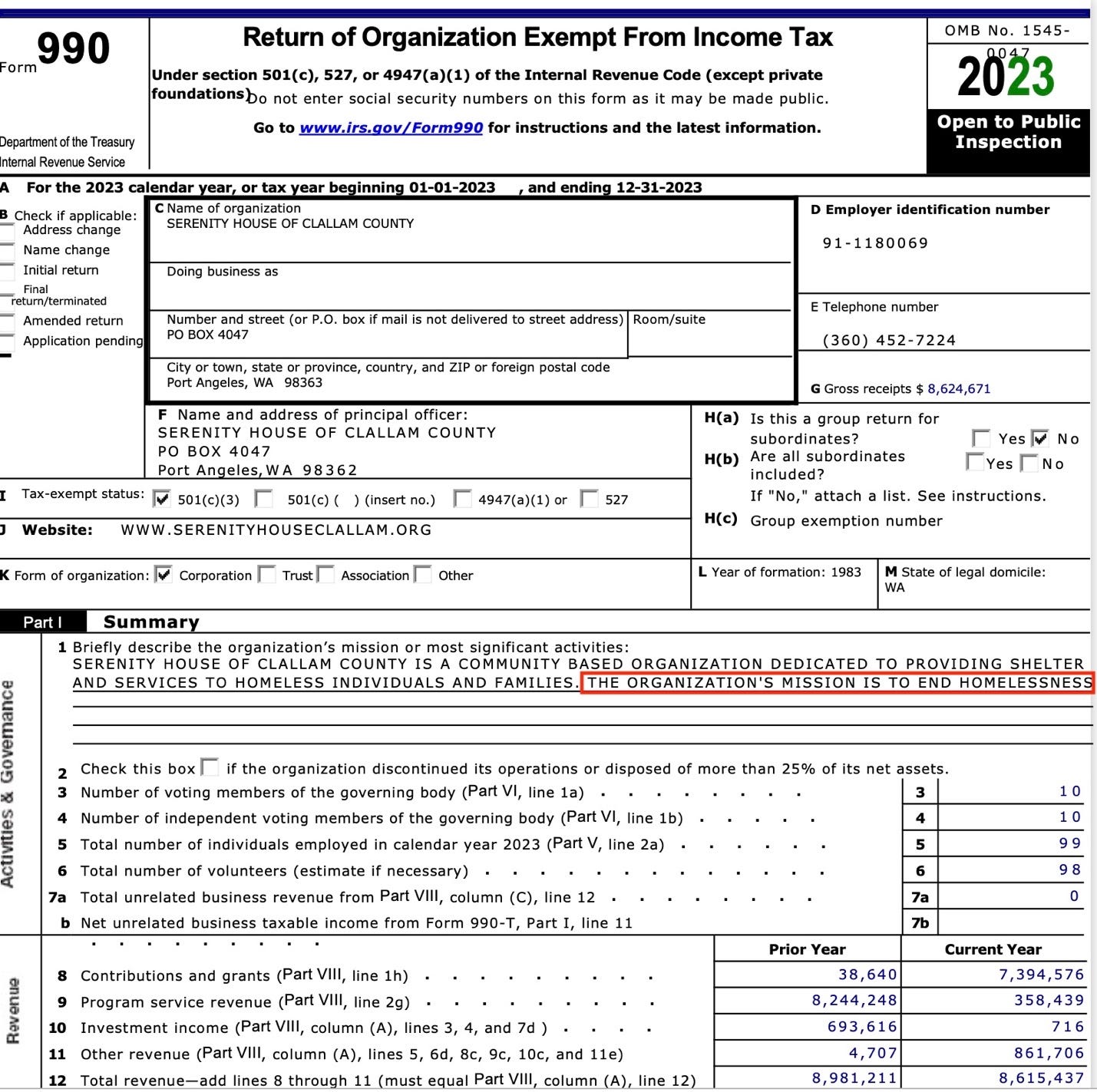

Serenity House’s own IRS Form 990 echoes the county’s aspiration:

“The organization’s mission is to end homelessness.”

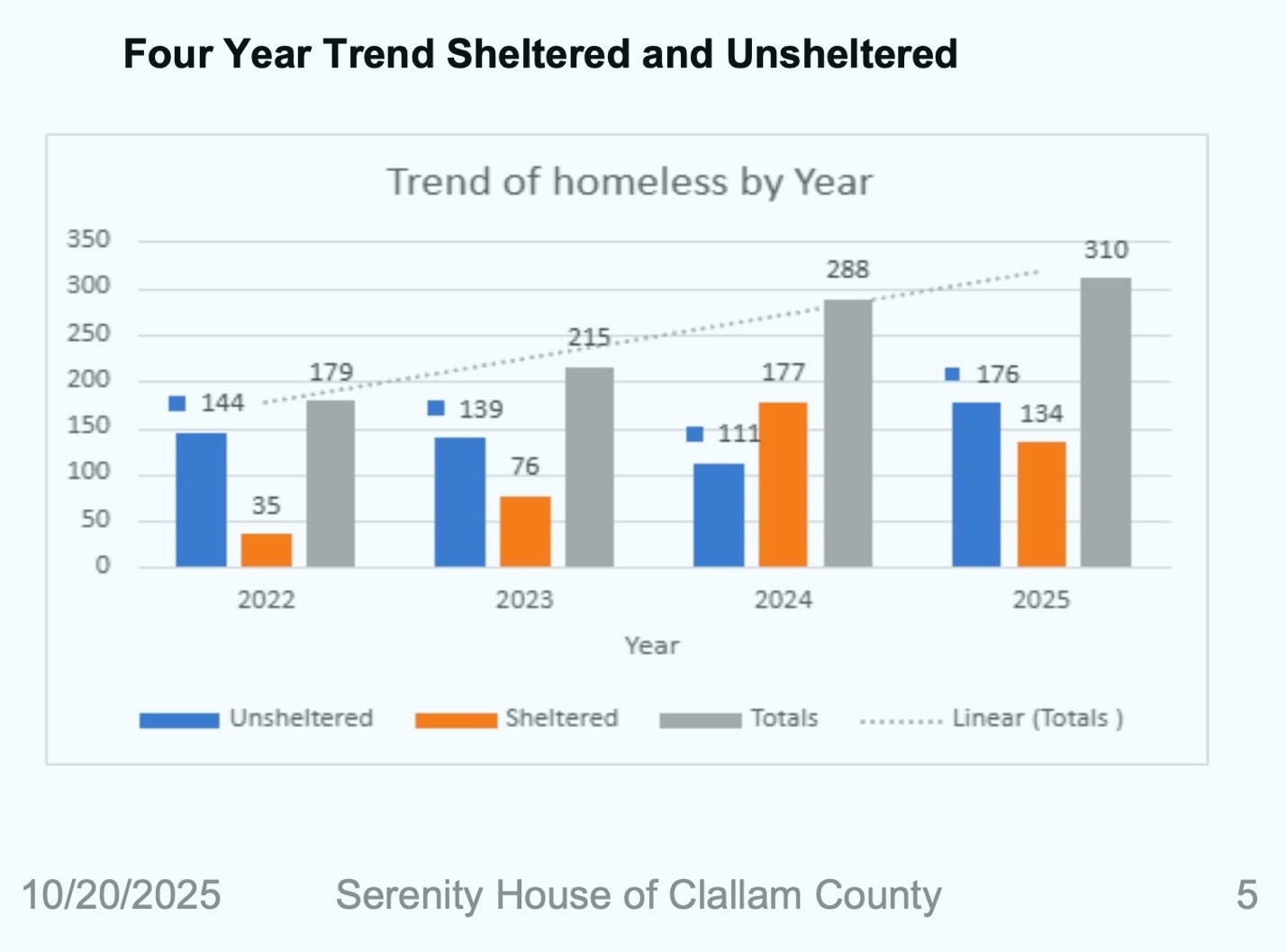

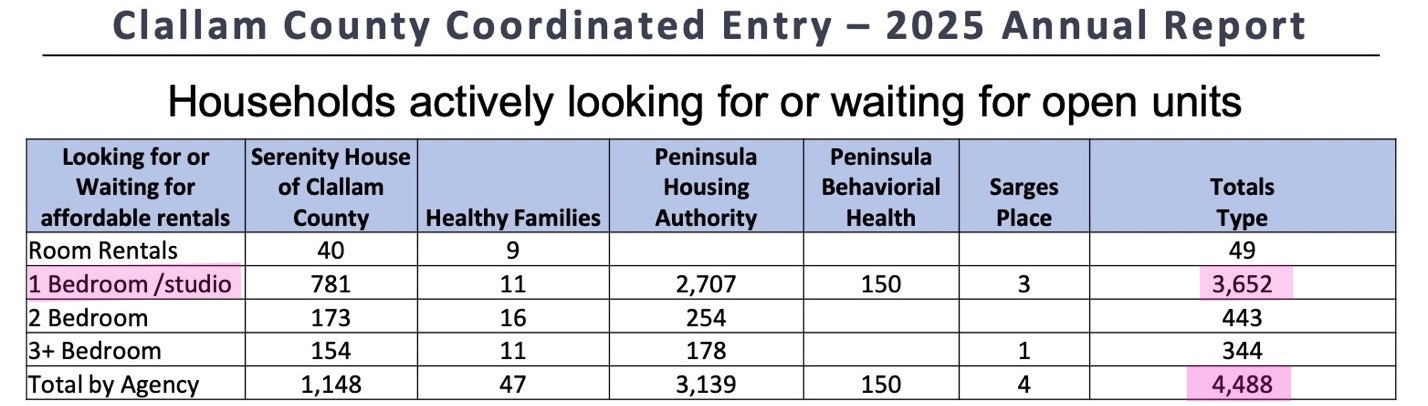

Yet homelessness continues to grow. According to the 2025 Coordinated Entry Annual Report (released by Serenity House), homelessness has risen 73% since 2022, including an estimated 176 unsheltered individuals.

Even more alarming is the 4,488-household waiting list for housing assistance — 26 times the Point-In-Time (PIT) count of unsheltered people. 81% of those households are seeking a one-bedroom or studio.

During a Homelessness Task Force meeting on December 2nd, when asked how the waitlist could be so inflated, compared to the PIT count, Serenity House Director Sharon Maggard responded:

“A lot of people couch surf.”

Debbi Tesch of Peninsula Housing Authority provided the more revealing insight:

“That does not represent just people living in Clallam County. Anybody can apply for our housing. It’s not unusual to have people living in California apply to live here.”

Tesch was unable to identify how many applicants are from outside the county, though she indicated that data may be available next week.

But why are NGOs tasked with ending homelessness in Clallam County allocating local resources nationwide when Clallam residents are already underserved?

The North View Question: Who Will It Really Serve?

Peninsula Behavioral Health’s North View project — a $12.75 million, 36-unit permanent supportive housing complex downtown — claims it will address the urgent need for affordable housing in Clallam County.

$3.85 million from Clallam County

$740,000 from the City of Port Angeles

$25,000 from First Fed

$750,000 from a local family

At $350,000 per unit, taxpayers deserve assurance that local needs come first.

Yet when asked whether Clallam residents generally receive priority on the county’s housing waiting list, Viola Ware — Director of Housing for Olympic Community Action Programs (OlyCap), which provides housing and emergency shelters in both Clallam and Jefferson counties — offered her perspective. She said:

“If you’re looking at low barrier and permanent supportive housing [like Northview], the prioritization is the need. A lot of us move to where we think our lives are going to benefit the most…that is a human thing. We seek what’s going to benefit us and our family.”

That answer sidesteps the obvious: Clallam has limited resources. Local needs should come first.

Importing Problems, Exporting Resources

This is not the only example of the Homelessness Task Force allocating local resources to non-local needs.

During the October 7th meeting, Serenity House Director Sharon Maggard described a single day in which a family of nine from Chicago and another family of twelve from outside Clallam both sought assistance. She said the Chicago family was fleeing the city to “avoid a raid.”

The family, traveling in a motorhome, was permitted to park in Serenity’s Evergreen Family Shelter lot while staff arranged hotel vouchers. Maggard explained:

“So, we need a process in the community when we get a big family like that… where do we place them for safety? We need to have some sort of reserve… someplace to call and say, ‘I need a hotel room so they can get showers for a few days.’”

Mariposa House Executive Director Beverly Lee then offered an eyebrow-raising solution:

“Mariposa House is happy to help. If someone is fleeing another state for their safety, I’m certain they’re going to qualify for one of the programs within our agency… I actually probably could have rented an Airbnb or something for a family that size.”

But if the family already had a motorhome, safe parking at Serenity, and access to meals and showers, why spend scarce local funding on hotel rooms—or even Airbnbs—while local homeless residents and crime victims remain underserved?

After utilizing Clallam’s resources, the family drove their motorhome to Oregon.

Manufacturing Scarcity

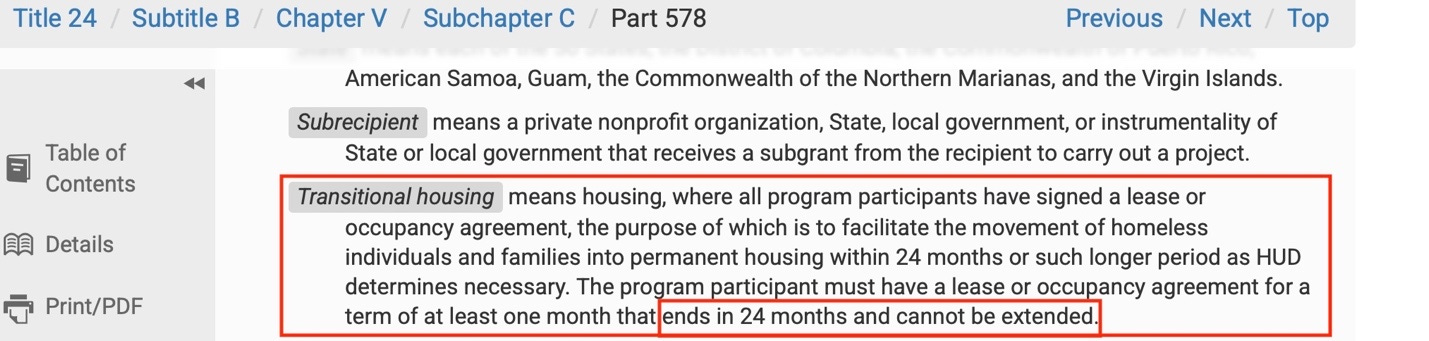

During the December 2nd Homelessness Taskforce Meeting, Serenity House Director Sharon Maggard explained how she circumvents the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) 24-month tenancy limit for transitional housing.

If a tenant leaves for even a single night and takes their belongings, Serenity House does not treat the return as a continuation of housing. Instead, staff re-enroll the individual as a new tenant, resetting the two-year housing eligibility clock back to day one.

This sleight of hand effectively converts transitional housing into de facto permanent housing, reducing the number of transitional housing slots available to those waiting for help.

Meanwhile, Serenity’s short-term shelter beds remain chronically underutilized.

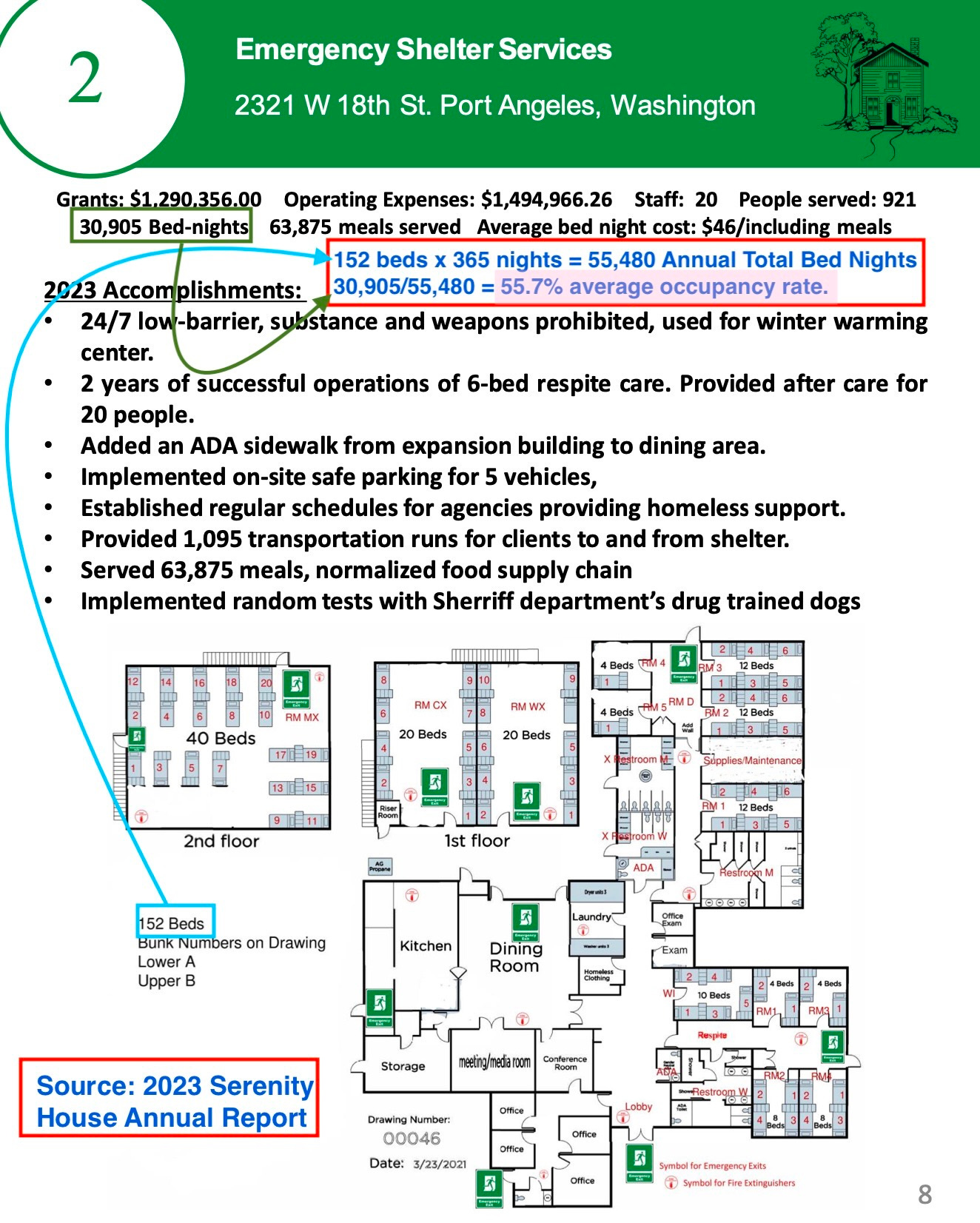

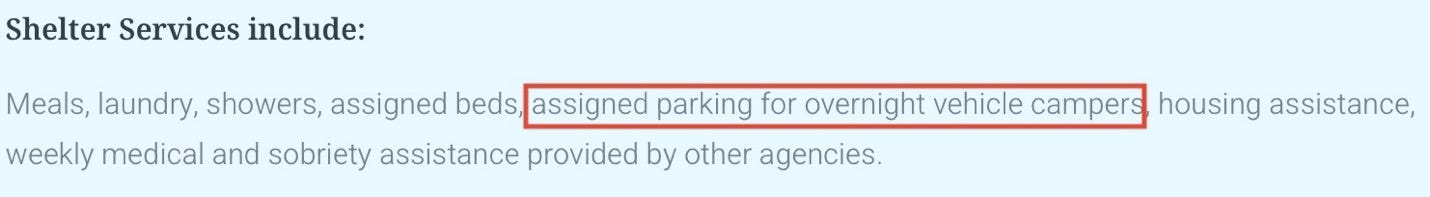

The shelter offers 152 beds, three free meals daily, laundry and showers, assigned beds, and assigned parking for overnight vehicle campers.

In its 2023 Annual Report, Serenity reported 30,905 bed nights.

152 beds × 365 days = 55,480 total annual capacity

30,905 ÷ 55,480 = 56% occupancy

That means an average of 67 beds sit empty every night — capacity sufficient to shelter nearly 40 percent of Clallam County’s unsheltered population.

This underused resource may be the single most immediate tool Clallam County and the City of Port Angeles have to reduce homelessness.

Why aren’t these beds filled?

A formerly homeless audience member said it plainly:

“I don’t understand why people would come to the shelter and leave but stay in the county… You can look for work, you can eat, you’re safe. Young people should stop wrecking the ecosystem and use the tools available.”

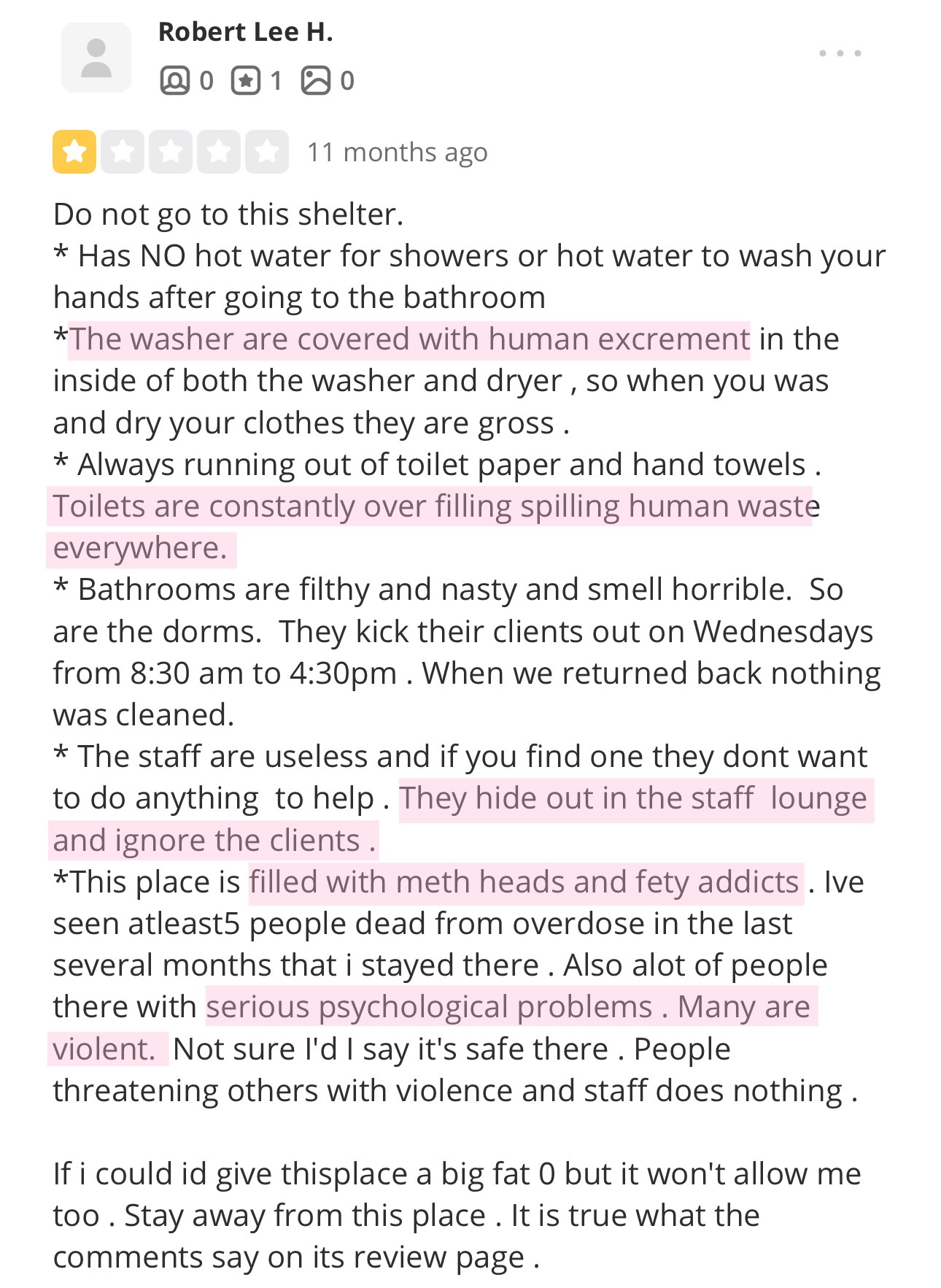

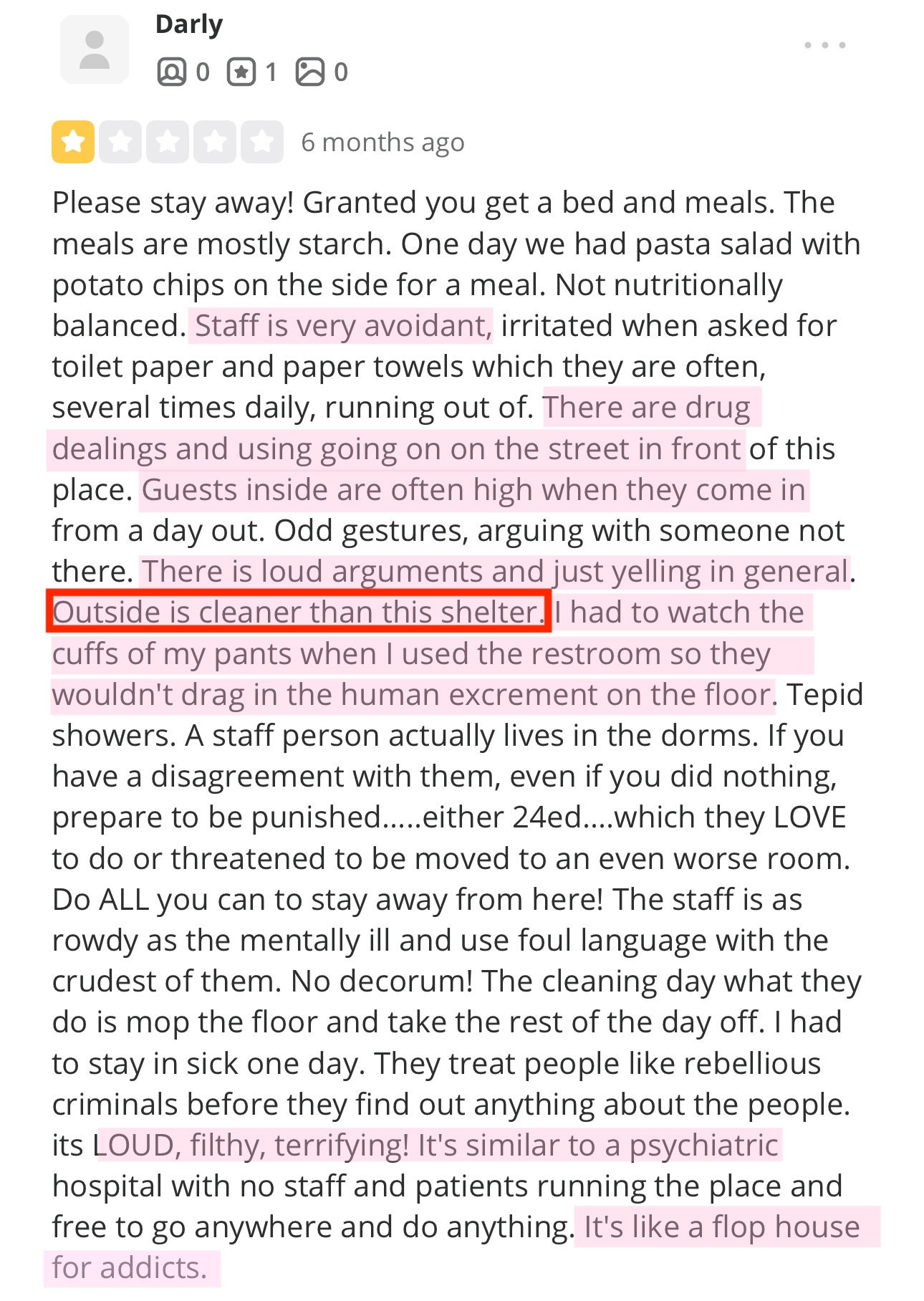

Serenity’s Yelp reviews confirm the same issues reported by the interviewed homeless:

filthy bathrooms

rampant drug use

lack of sleep

theft of personal property

unsafe atmosphere

unresponsive staff

Given these conditions, many prefer a soggy tent along Tumwater Creek to a bed inside Serenity House.

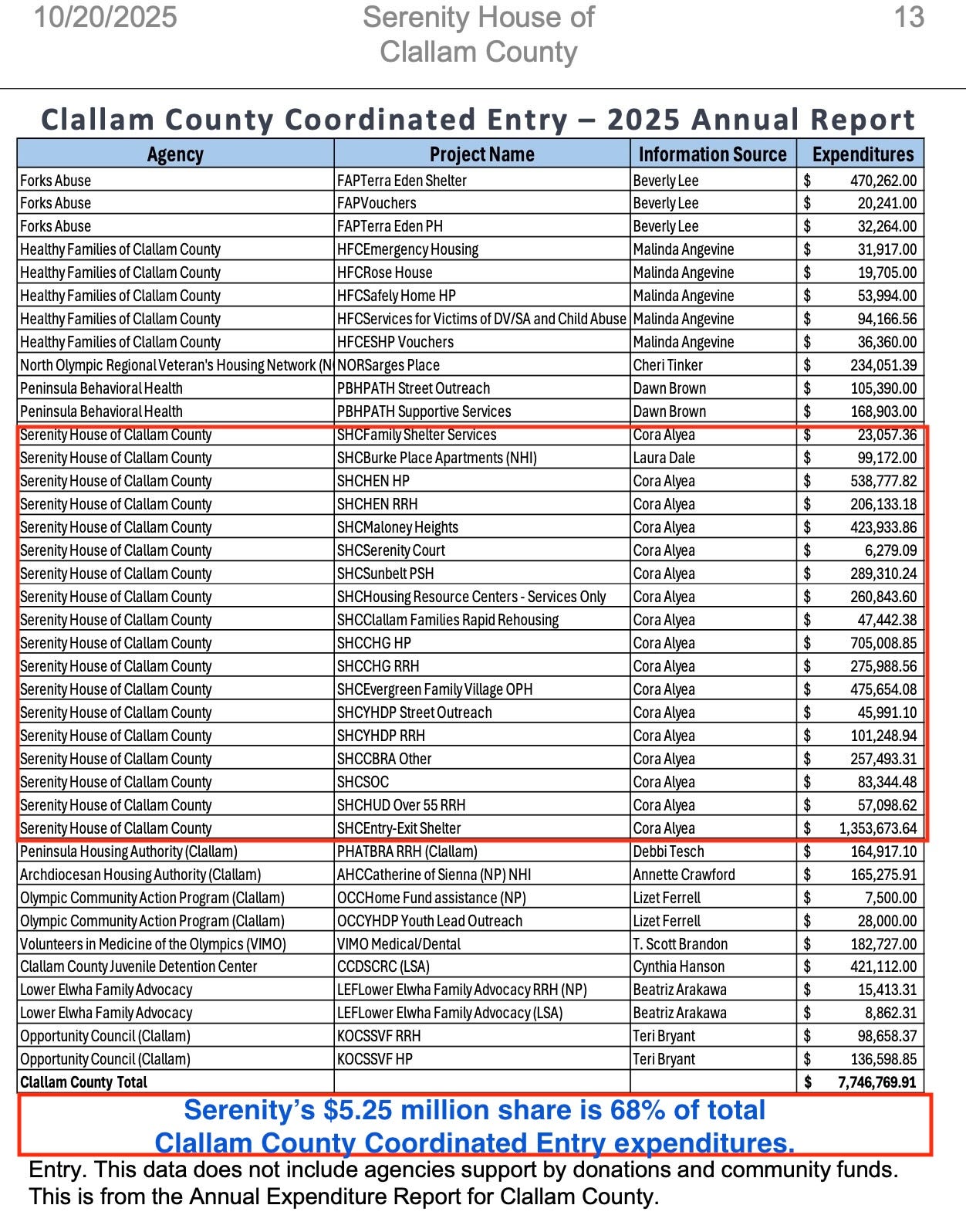

Yet Serenity House continues to operate Clallam County’s Coordinated Entry system — the mandatory gateway for all housing services — and receives millions in taxpayer funding every year, largely from state and federal grants.

The $118,000 Parking Lot With No Customers

Even as the county underuses its current resources and diverts aid to out-of-county applicants, commissioners fund local programs that attract no participants.

The Safe Parking Program at Sequim’s Trinity United Methodist Church — a two-year, $100,000 taxpayer-funded pilot program — provides 3–5 spots for people living in vehicles.

Homelessness Task Force members explain the reasoning:

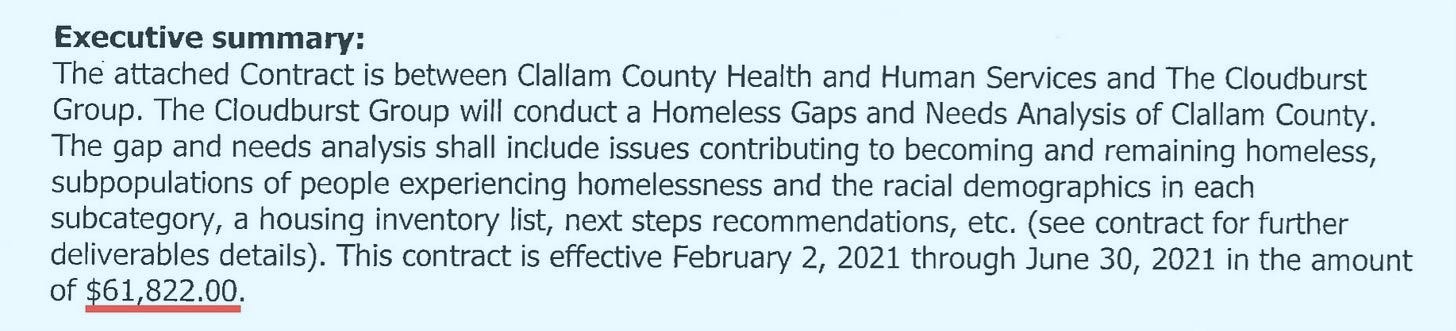

“The initial conversation around the safe parking program was how needed it was in our community – that we didn’t have anything like it. It was brought up in the 2021 Gaps and Needs analysis as a definite need in our community.”

The Cloudburst Group, a consulting firm based in Maryland, was paid $62,000 to produce the Gaps Report that recommended safe-parking programs.

All while:

Big-box stores offer safe overnight lots

Free camping/parking apps provide multiple legal options, and

Serenity already offers free parking.

To date, not a single person has checked into Trinity’s safe-parking program.

County officials appear to have overlooked the program’s core barrier: the church’s insurance requires vehicle occupants to hold valid registration — a requirement many prospective participants cannot meet or legally resolve, even though funds are available to cover expired insurance or registration.

Despite the lack of registration-compliant demand, the Task Force requested an additional $18,000 for the program, bringing total funding to $118,000. During the December 8th work session, commissioners signaled they were open to approving the increase.

Freedom to Choose?

Homelessness Task Force members have repeatedly defended the “freedom” to live outside:

· “It’s difficult to say that’s what everybody should do. It [living in the shelter] works for some, but not everybody wants to make those [choices].”

· “It just depends on their unique situation.”

· “Some of them don’t want to be housed. Some of them like the freedom of being homeless and doing what they want to when they want to.”

· “If someone is choosing that tent on the sidewalk, it’s their choice.”

Only Task Force member John DeBoer — formerly homeless — said what no one else on the Taskforce would:

“It’s their choice. It is not their sidewalk.”

Yet the county aggressively enforces property-code violations against private landowners while simultaneously tolerating illegal camps, trash accumulation, unsafe structures, and ongoing environmental damage on its own public lands.

A Better Way

Homelessness continues to grow in Clallam County – even as more funding is funneled to NGO’s. But, solutions are within reach – without millions more in spending. It’s time for our leaders to connect the dots:

1. Prioritize local residents for housing allocations.

HUD allows prioritization of people physically present in the community. Clallam should serve its own first.

2. Fix Serenity House’s shelter.

A cleaner, safer, structured environment would dramatically increase shelter usage. 67 open beds on average could house 40% of the currently unsheltered.

3. Remove the option of living outside on public land.

It is time for city and county officials to enforce their own ordinances on their own land. Unpermitted landfills, open trash piles, dumping in critical areas, improper disposal of human waste, unsafe and unpermitted structures, and ongoing illegal activity would never be tolerated on private property — and they should not be tolerated on taxpayer-owned property either. Public land must be held to the same standards as everyone else.

4. Acknowledge the link between homelessness and addiction.

A walk downtown and along Tumwater Creek proves that substance abuse among the homeless is far higher than the “1 in 5” claimed by Dr. Allison Berry, the county’s public health officer.

5. Reduce the cash that fuels addiction.

Chelsea Jones put it bluntly:

“Every dollar I got flying a sign went to drugs.”

Discouraging panhandling at high-traffic locations cuts off easy money and removes the financial incentive that attracts dealers and perpetuates use.

6. Enforce drug distribution laws.

Dealers openly selling in the Safeway lot across from the Sheriff’s Office is unacceptable.

Last week, a witness reported seeing multiple dealers receiving drug supplies in the Safeway parking lot on Lincoln Street — directly across from the Sheriff’s Office. One of the dealers even attempted to sell drugs to the witness.

7. Focus funds on the greatest net gain.

Improving occupancy through a clean, safe, and well-operated shelter would be far more effective than providing three to five parking spaces.

The County of Least Resistance

The word is out, and Clallam County has become:

Where harm-reduction supplies are abundant.

Where enforcement is lax.

Where cash for drugs flows freely.

Where leaders make it easy to live in the woods.

Where local housing is offered to outsiders.

Clallam has become a magnet for homelessness and a drug economy imported from elsewhere.

A CC Watchdog comment summed it up perfectly: “The plan is NOT working…”

Chelsea Jones moved 3,000 miles to live freely in the woods on the Olympic Peninsula.

Drugs and homelessness thrive where conditions are easiest — lax enforcement, easy money, abundant drug-use supplies, and quiet places to camp and use. The policies embraced by county commissioners and city council members have made Clallam the county of least resistance.

Raise the bar and watch things change.

What can you do?

County Commissioners Mike French, Mark Ozias, and Randy Johnson control the purse strings that keep this system running. If you believe Clallam County should prioritize local residents, fix unsafe shelters, stop funding empty programs, and enforce the law on public land, tell them.

Email the commissioners and ask them to:

Prioritize Clallam County residents for local housing resources.

Require measurable results and full transparency from NGOs before renewing or expanding funding.

Fix conditions at Serenity House so those 67 empty beds a night are actually usable.

Stop spending money on programs with no participation, like the Trinity safe-parking lot.

Enforce existing laws on public property the same way they are enforced on private land.

All three commissioners can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov.

A short email from you will do more than another plan, another task force, or another outside consultant. Let Commissioners French, Ozias, and Johnson know that Clallam County residents are watching how they spend our money — and that it’s time to try something that works.

Last week, Jake Seegers asked readers how confident they were that major policy changes in local government are communicated clearly and openly to the public. Of 61 votes:

98% were not confident

2% were somewhat confident

No one was “very confident” or “unsure”

Editor’s Note: CC Watchdog editor Jeff Tozzer also serves as campaign manager for Jake Seegers during his run for Clallam County Commissioner, District 3. Learn more at www.JakeSeegers.com