As the Clallam County Charter Review Commission reaches its final meetings, unresolved ethical breaches, selective rule enforcement, and escalating efforts to control who may speak—and how—have come to define the process. What was intended to be a nonpartisan exercise in grassroots democracy instead exposed how gatekeepers of influence protect their own, chill dissent, and bend procedure to avoid accountability.

A Second Scandal, No Consequences

Charter Review Commissioner Jim Stoffer appears poised to emerge unscathed from a second serious controversy involving the misuse of his elected position. This time, the issue centers on his sharing of an email clearly labeled attorney-client privileged—without authorization from the full commission.

At the most recent meeting, a representative from the Clallam County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office was scheduled to explain the legal implications of such a disclosure. That presentation did not occur. Civil Deputy Prosecuting Attorney Dee Boughton was reportedly ill and neither attended nor provided a written opinion. As a result, the commission—and the public—were left without guidance on a matter involving confidentiality and ethics.

What Never Makes the Agenda

Equally notable was what wasn’t discussed.

An agenda item to consider censure and formal apologies from Commissioners Jim Stoffer and Paul Pickett—Pickett previously referred to public commenters as ignorant racists—was never placed before the commission. The decision rested with the Executive Committee: Susan Fisch, Chris Noble, and Mark Hodgson.

This omission followed a now-familiar pattern. Matters involving Commissioner Stoffer—his taxpayer-funded private security detail, the sharing of confidential information—are routinely excluded from the agenda and forced instead into procedural limbo. Notably, this selective gatekeeping has been applied to only one commissioner:

Me.

Public Comment, Unevenly Policed

The second-to-last meeting drew an unusually large audience. Much of the public comment focused on Stoffer’s disclosure of confidential information.

During that period, public commenter Brian Grad turned away from the public comment podium and addressed the audience directly—accusing the gallery of “throwing stones and sticks” at Stoffer and urging them to engage in dialogue “so we can get on with our lives.”

Chair Susan Fisch allowed it.

This was a marked departure from Fisch’s past conduct. She has previously enforced comment rules rigidly—cutting speakers off for addressing anyone other than the commission, insisting comments strictly relate to posted agenda items, and even prohibiting commissioners from being mentioned by name. None of those rules were enforced with Grad.

Grad’s volume rose. The exchange grew heated—more so than the incident that earlier prompted Fisch to arrange a private security guard for Stoffer. Only when members of the gallery began responding did Fisch intervene, asking, “Will you let me handle this?”

The problem is that many in the room no longer believe Susan Fisch has been handling things impartially.

A Familiar Figure

Grad is not new to controversy. He previously drew public attention at the Clallam County Fair after appearing at a political booth wearing a hat, accusing a sitting U.S. President of being a pedophile. The incident prompted formal complaints from fairgoers.

County Parks, Fair, and Facilities Director Don Crawford responded by citing First Amendment protections. However, the issue raised then—and now—was not speech alone, but consistency, and the opinion that a vendor discussing pedophilia at a family-friendly venue is inappropriate.

Every vendor at the fair signs a contract prohibiting vulgar, offensive, or obscene material and authorizing management to remove items that undermine the fair’s family-friendly character. The question raised was simple: would those same rules have been applied had the accusations targeted local officials?

Equity requires consistent enforcement—not selective tolerance.

Who Gets to Speak?

That question resurfaced at the Charter Review Commission.

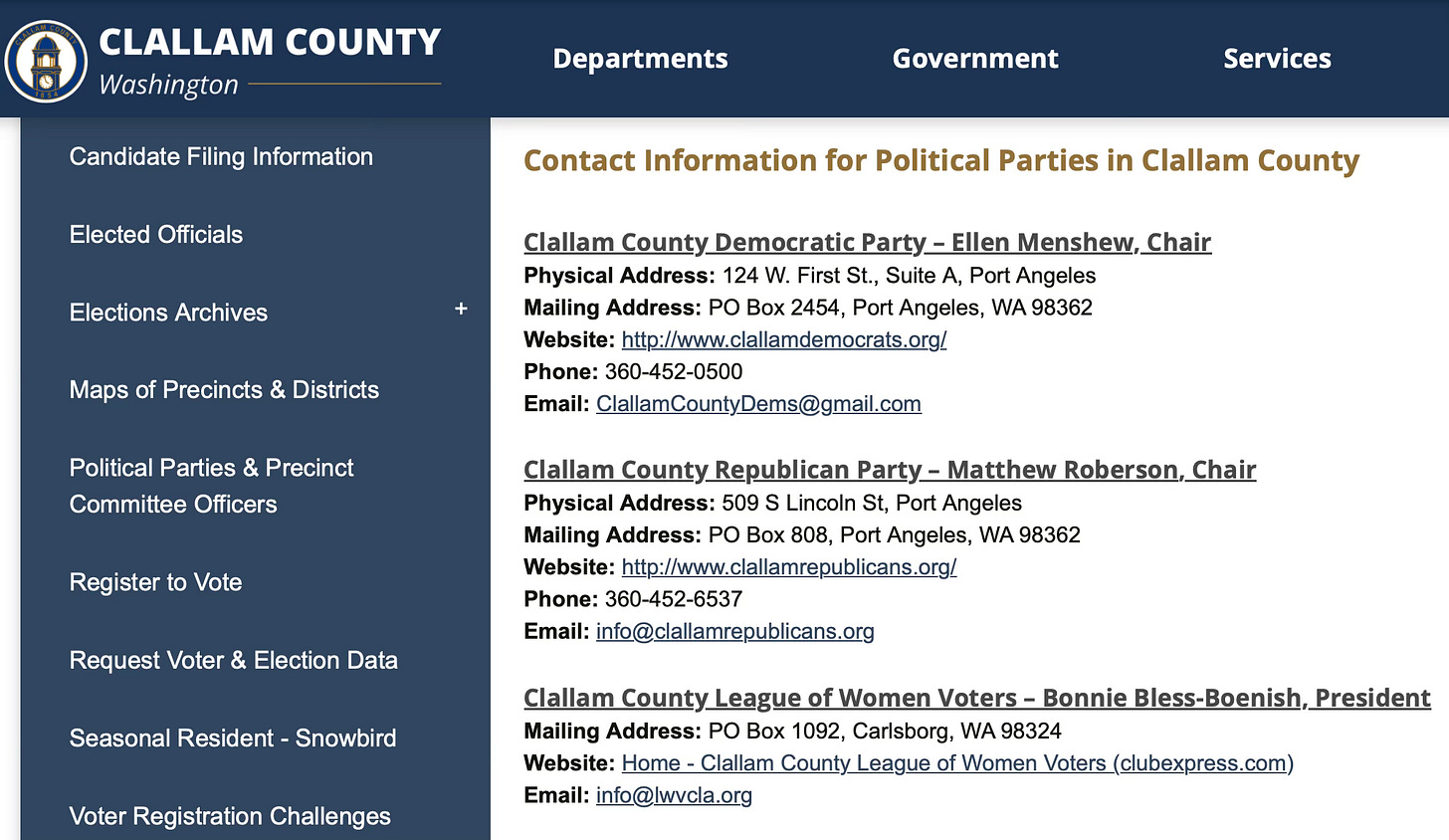

League of Women Voters President Bonnie Bless-Boenish addressed the commission—not to condemn the breakdown of decorum or reinforce equal treatment—but to highlight that one commenter “does not reside in Clallam County.” She suggested speakers should be required to state their name and where they are from so that “the people commenting are the people who actually live here.”

That suggestion is incorrect as a matter of law.

Washington’s Open Public Meetings Act (RCW 42.30) does not require speakers to identify themselves, state residency, or even be residents at all. Anonymous and out-of-town public comment is lawful. Governments may request information, but they may not require it as a condition of speaking.

This matters—because Clallam County has a documented history of retaliating against public commenters who challenge prevailing political interests.

From Comment to Retaliation

In 2023, Towne Road supporters were subjected to a month-long investigation led by Commissioner Mark Ozias, the Sheriff, and the Prosecuting Attorney. Earlier this year, Commissioner Jim Stoffer attempted to have public commenter Eric Fehrmann removed from a volunteer position at Stoffer's church, alleging harassment and intimidation.

Retribution for speech is not theoretical in Clallam County. It is real.

That context mattered when Chair Susan Fisch interrupted public commenter Shenna Younger after Bonnie Bless-Boenish, seated in the audience, waved to signal that Younger is the one who doesn’t live here. Younger was shouted down by Fisch and muted, and was only allowed to continue after the County Administrator clarified—on the record—that public commenters are not required to state their name or place of residence.

Younger now lives elsewhere in Washington, but when she lived in Sequim, she was the whistleblower who alerted the Sequim School Board that Jim Stoffer was sharing confidential information. Her stake in local governance is undeniable.

The Irony at the Center

Susan Fisch is a retired judge, a role grounded in the fair and impartial application of the law. She ran for Charter Review Commissioner as Secretary of the League of Women Voters of Clallam County, an organization that describes itself as nonpartisan and dedicated to defending democracy. Bonnie Bless-Boenish serves as president of that same organization.

Both have had a front-row seat to eleven months of selective rule enforcement, chilled dissent, and preferential treatment.

Their concern, it seems, is not abuse of power—but who gets to speak.

One Final Amendment

At the commission’s final meeting, next Monday, Vice Chair Chris Noble is expected to propose a new amendment governing confidential communications—an amendment that would formalize rules Stoffer already violated.

Rather than focusing on reforms the public relied on them to deliver, the commission appears poised to spend its last act protecting itself from its own failures.

When Everything Becomes Political

Taken together, these incidents point to a deeper and more troubling reality: Clallam County government has become overtly political in places where neutrality is not optional.

The Prosecuting Attorney’s Office has stated it cannot investigate the vandalism of the Doc Holliday timber parcel by the self-described “Troublemakers” because of political implications. Meanwhile, Towne Road supporters—ordinary citizens—were unknowingly subjected to a month-long investigation in 2023 involving elected officials, law enforcement, and prosecutors. At the same time, the Sheriff’s Office declined to remove trespassers from the unfinished Towne Road site, citing that the issue had become “political.”

Remember that: Clallam County made a road political.

Within the Charter Review Commission, the Executive Committee—Susan Fisch, Mark Hodgson, and Chris Noble—has repeatedly favored political allies, shielded certain commissioners from scrutiny, and suppressed dissenting voices through selective agenda control and uneven rule enforcement. The result has been a process that looks less like neutral civic review and more like managed outcomes.

The League of Women Voters is officially listed by Clallam County Elections as a nonpartisan civic organization. However, in practice, its leadership has acted as a political advocacy group—passing signals to Chair Fisch during meetings, singling out speakers, and advancing viewpoints that align with a particular ideological bloc while framing dissent as illegitimate. That is activism, not neutral civic education, regardless of how it is branded.

This politicization has consequences. When prosecutors cannot investigate vandalism, when citizens are quietly investigated for speaking out, when public comment is curtailed based on alignment, and when basic enforcement decisions are deferred because they might upset political allies, equal treatment under the law erodes.

Clallam County did not arrive here overnight. But the past year has made something unmistakably clear: institutions that are supposed to operate impartially have drifted into partisan territory, and those entrusted to safeguard fairness have instead become gatekeepers of influence.

The question now is not who benefits from this arrangement—but whether the county is willing to restore the principle symbolized by a blindfolded Lady Justice: law applied fairly, without fear or favor, politics aside.

Democracy cannot function where neutrality is optional—and civic participation cannot survive where power decides who gets heard.

A Path Back to Neutrality

Clallam County does not need new rules or tighter controls on public participation. It needs a return to basics: neutral governance, consistent rule enforcement, and equal treatment under the law—regardless of politics or affiliation.

That means applying public comment rules evenly, addressing ethical breaches openly rather than avoiding them, drawing clear lines between activism and governance, and ensuring citizens can speak without fear of retaliation. The Charter Review Commission should finish its work focused on serving the public—not protecting individuals or managing dissent.

Call to Action

With the Charter Review Commission nearing its final meeting, the public still has a voice. Residents can submit written comments to the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov, who distributes them to all commissioners.

Trust is rebuilt when fairness is visible. Clallam County can move back toward nonpartisan governance—but only if citizens insist on it now.