Clallam County is pushing ahead on a redesign of Voice of America Road and the Kitchen-Dick/Lotzgesell curve — the gateway to the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge. But after the Towne Road debacle, public faith in the County’s ability to complete a project transparently and competently has eroded. Voice of America Road now serves not only recreational traffic but also access to a refuge newly managed by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, which includes a 50-acre commercial oyster operation. Residents say the issue isn’t disagreement over road improvements; it’s the belief that the County no longer tells the full story before it breaks ground.

The Hangover From Towne Road

Towne Road was supposed to be simple: a designed, engineered, funded, and publicly supported project. Instead, it became a symbol of government unpredictability. Commissioners changed the scope at the eleventh hour, halted work, inflated costs, and forced residents to fight just to reopen a public road that had already been approved.

That experience fundamentally altered how this community sees its county government. People came away believing that the County can — and will — reverse itself without warning, ignore public feedback, and obscure the true costs until it’s too late for taxpayers to object.

It’s that climate that the Voice of America Road redesign begins.

A Public Entrance the County Can’t Afford to Mishandle

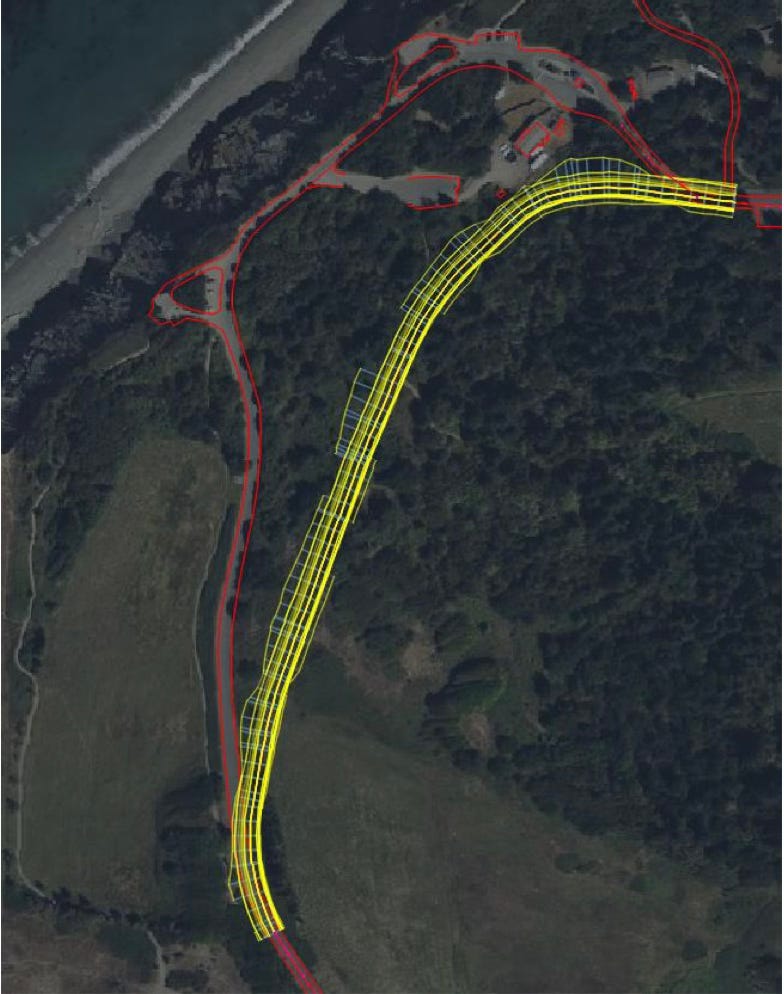

Voice of America Road is the sole public access to the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge, one of the most visited natural areas in the county. With the Refuge now managed by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe and home to a large commercial oyster operation, traffic patterns and land use pressures have shifted. Change may be necessary. But residents want to know exactly what the County is trying to accomplish— and why.

Instead, they’re hearing generalized references to “safety,” vague timelines, and a project bundled together with unrelated components. After Towne Road, people expect detailed explanations, not broad assurances.

The Curve: A Redesign Stuck in the Past

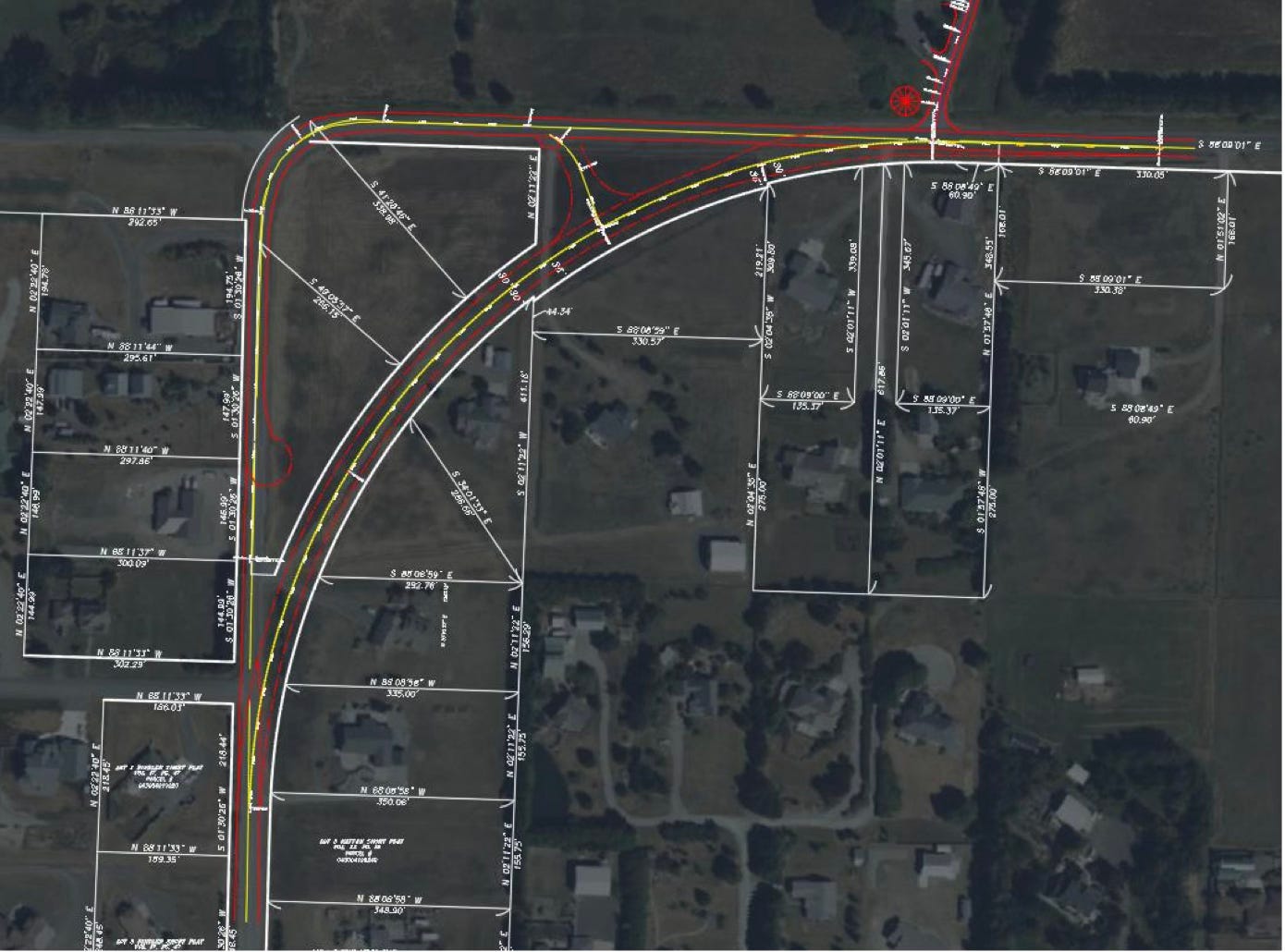

At the County’s recent public meeting, the message was unmistakable: almost no one supports the current plan to soften the Kitchen-Dick/Lotzgesell curve. The design is based on a decades-old concept from the 1980s, long before today’s development, traffic demand, or wildlife activity. Residents worry the proposed alignment will increase speeds, reduce safety, and create new hazards for pedestrians and cyclists using Lotzgesell Road to access the refuge.

The County cites seven accidents in the area since 2018 as justification. Yet two involved intoxicated drivers — a fact the public believes undermines the narrative that geometry alone is to blame. People aren’t rejecting improvements; they’re rejecting outdated, incomplete reasoning.

Some residents favor a modern approach — including roundabout options and updated engineering — but feel the County is trying to force an old plan into a new reality.

A New Red Flag: Commissioner Ozias and Park Co-Management

Public trust was strained further when Commissioner Mark Ozias, after attending a conference earlier this year, remarked that counties across the nation are entering “co-management” arrangements for their parks with tribal governments. While the concept may be of interest to policymakers, many residents were taken aback that such a significant shift in how county parks might be governed was being discussed without any prior public conversation.

This concern comes on the heels of several recent actions that have left citizens feeling sidelined. The County’s push for a Cultural Access Tax, the approval of new fees for the Clallam Conservation District despite Jake Seegers submitting 1,032 signatures in opposition, and the commissioners’ apparent reluctance to take even basic steps—such as responding to federal agencies or actively engaging with community questions — have all added to a growing sense of disconnect.

Again and again, major initiatives seem to be shaped behind the scenes and only presented to the public once they are effectively decided. In that environment, even routine statements about policy ideas trigger suspicion, because residents no longer feel they are part of the process. For a frustrated community, this latest disclosure felt like yet another example of decisions forming quietly, without the participation or even the awareness of the people who will live with the consequences.

More Than a Road Project — A Pattern

Seen individually, each of these issues could be explained. But taken together, they form a pattern that residents can no longer ignore.

Towne Road was altered without warning.

Refuge administration shifted quietly.

A large aquaculture operation was approved inside a protected area despite legal challenges.

Notices for the Voice of America project omitted critical details.

And now a county leader acknowledges exploring new governance models without informing the public beforehand.

The common thread running through each is the same: decisions made first, explained later.

People are not fighting change — they’re fighting uncertainty, inconsistency, and a sense that their government is not being forthright.

A Path Toward Restoring Public Trust

Clallam County can repair its standing with the public, but it will require an intentional reset.

Residents want the Voice of America Road project separated from the curve redesign so each can be evaluated on its own merits. They want updated safety data, modern engineering, and clear explanations about what problems these projects actually solve. And they expect commissioners to engage openly, answer questions, and restore the basic principle that public lands and public roads require public consent.

This Road Belongs to the Community

Voice of America Road serves families, hikers, birdwatchers, tourists, and local residents. It connects the public to public land and, through tourism, contributes to economic prosperity. Decisions about its future should never be made in a vacuum.

If you believe this redesign deserves transparency and honest evaluation, now is the time to speak:

Attend a Board of County Commissioners meeting.

Submit written comments to county commissioners. All three can be reached by contacting the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov

Share concerns with neighbors and community groups.

Ask for updated studies, open dialogue, and clear justifications — before the project reaches a point of no return.

Clallam County can get this right. But only if the public insists on it.

Access the County’s redesign plans by clicking here.