Every week brings a new contrast between what local government says it values and what its decisions actually reveal. Whether it’s a farmer’s market that has to be scrubbed of human waste while a “Portland Loo” sits unused a few feet away, or a public hospital board holding special meetings without recordings, or millions in Climate Commitment Act money bypassing the people who pay the bill. Any way you slice it, things just aren’t adding up in Clallam County.

The Farmer’s Market on Cleanup Duty

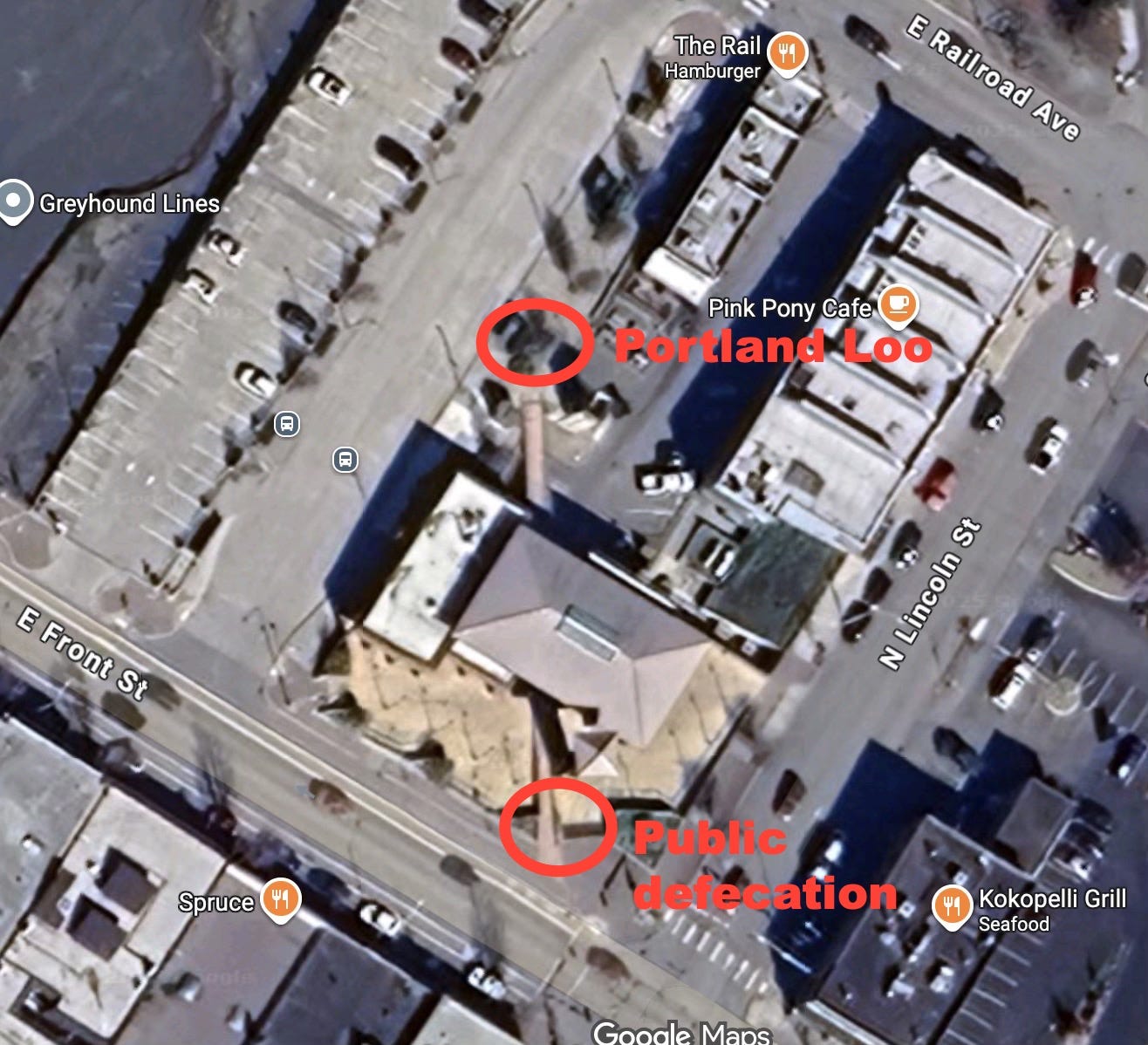

A Facebook video making the rounds shows what it now takes to prepare for the year-round Port Angeles Farmers Market at Gateway Plaza: before vendors arrive, crews must remove human feces and scrub down the plaza.

Three years ago, Port Angeles spent $729,544.36 to purchase and install three 24-hour “Portland Loo” restrooms — one of which sits less than 100 feet from where people repeatedly defecate.

Taxpayers are continually asked to fund more homelessness programs, more “harm reduction,” more free paraphernalia, and more luxury homeless housing. But how invested are those receiving the services? If someone would rather defecate on the farmer’s market plaza than walk 100 feet to a quarter-million-dollar public restroom, something is broken — and it isn’t the plumbing.

Land Back for Kids?

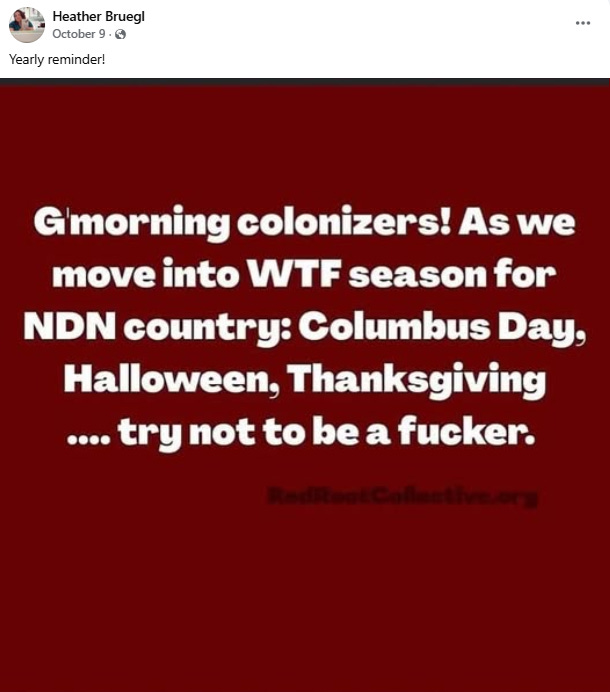

The North Olympic Library System is promoting a children’s book called What Is Land Back? — a book that argues all public land should be transferred to tribes. Its author, Heather Bruegl, reinforced her message on Facebook:

Reasonable people can debate history, sovereignty, and tribal rights. But is the children’s section the appropriate venue for pushing political guilt onto kids who haven’t harmed anyone? A library’s role is to broaden understanding — not to funnel children into one side of a complex cultural argument.

And if you aren’t subscribed to Clallamity Jen’s Substack, you’re missing the best laugh of your day.

Election Lessons and the $200 Million City Budget

This election cycle showed how outside money — including from Seattle interests and sovereign tribal governments — can still sway small-town races, as seen in LaTrisha Suggs’ victory. But it also showed something else: her opponent, who nearly unseated her, isn’t going anywhere and remains active in the city he loves.

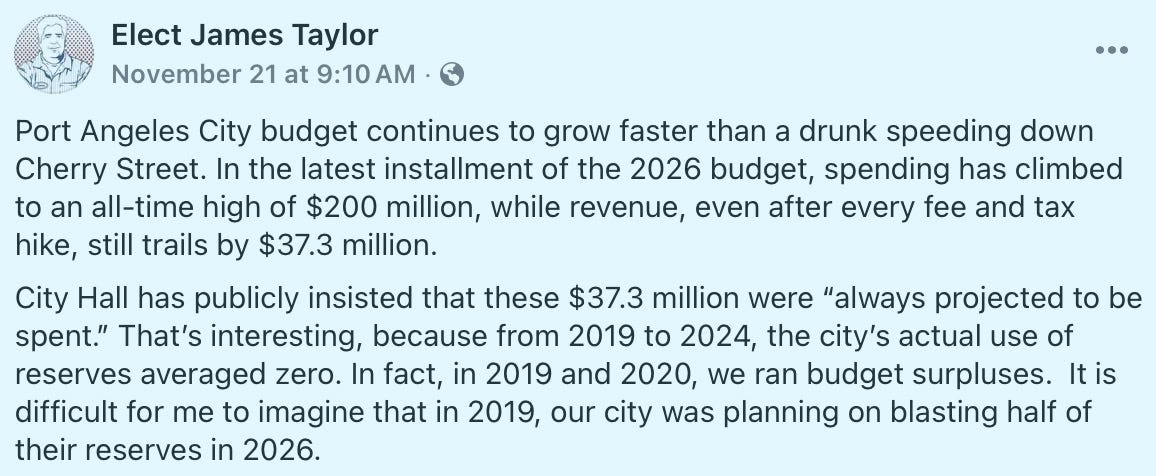

That’s good, because Port Angeles will need watchdogs. As James Rocklyn Taylor put it: “The city budget continues to grow faster than a drunk speeding down Cherry Street.”

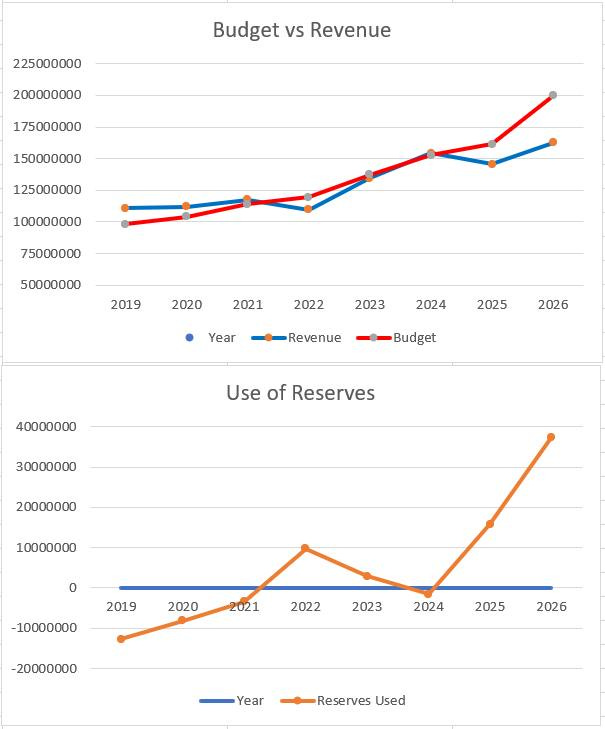

City spending is now at an all-time high: $200 million, with a projected $37.3 million gap even after every fee and tax increase. City Hall insists these millions were “always projected to be spent,” yet from 2019 to 2024 the city averaged zero withdrawals from reserves — even posting surpluses in 2019 and 2020.

It strains belief to imagine that back then, Port Angeles was quietly planning to blow half its reserves in 2026.

Seattle Retreats From Harm Reduction — Clallam Doubles Down

As Clallam County increases spending on harm reduction, Seattle — the birthplace of many of these policies — is quietly backing away. A recent Seattle City Council amendment limited taxpayer spending on “harm reduction” kits. Councilmember Sara Nelson compared distributing certain supplies to:

“…giving a loaded gun to somebody who’s suicidal… distributing these supplies runs counter to overdose prevention and treatment efforts and is, frankly, cruel.”

Seattle is signaling a course correction. Clallam County is accelerating in the opposite direction. Only time — and data — will tell which approach actually saves lives.

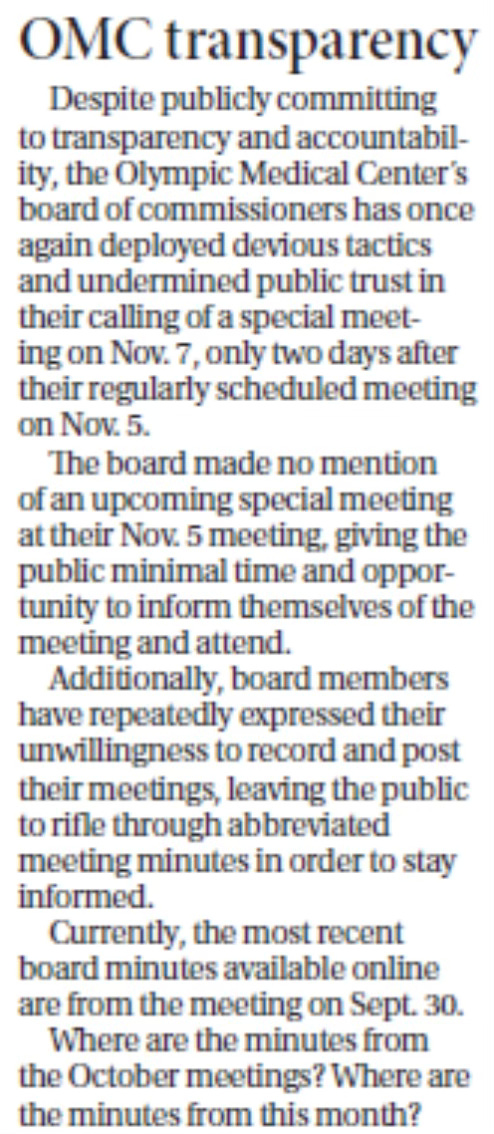

OMC’s Transparency Problem

Ellen Menshew, chair of the Clallam County Democratic Party, is publicly criticizing Olympic Medical Center for its lack of transparency. She argues the OMC board has “deployed devious tactics and undermined public trust” by scheduling special meetings and holding meetings without recordings, while failing to publish minutes from prior meetings.

Her question is simple and fair: “How is the public expected to stay informed of the commission’s work when meetings are not recorded, schedules are changed at the last minute, and meeting minutes are not current?”

OMC is a public hospital — not a private equity firm. Taxpayers just doubled their contributions through a levy lid lift. They deserve basic accountability. Menshew is right.

A Realignment Project With Real Questions

Clallam County will hold a neighborhood meeting on December 2nd to discuss the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge Access Improvement Project, including the Kitchen-Dick/Lotzgesell curve realignment. The project moves the access road away from eroding bluffs and softens a sharp bend.

Notices were sent to households within 1,000 feet of the project. Critics argue that softening the curve will encourage speeding. Others say the county should prioritize dangerous intersections like Old Olympic Highway/Cays or the repeatedly flooded 3 Crabs Road — especially after the county and tribe reengineered Meadowbrook Creek.

The meeting is your chance to ask questions — and ensure the county isn’t prioritizing the “nice to have” over the “need to fix.”

The meeting will be held on Tuesday, December 2nd, 2025, at 6 pm at the Dungeness Schoolhouse, 2769 Towne Rd., Sequim.

Activism for Me, Not for Thee

When Lisa Dekker isn’t trespassing on DNR land and vandalizing $10,000 in public property — an act she was celebrated for in activist circles — she writes political commentary for Puget Sound Advocates for Retirement Action.

In June, she condemned a “flagrant refusal to follow the law” in national politics. If she is emphasizing that a society relies on shared respect for legal norms, she’s not wrong — which is exactly why her message rings hollow.

You can’t preach about the importance of the rule of law while boasting about breaking it. Accountability doesn’t stop being important when it becomes inconvenient to your cause.

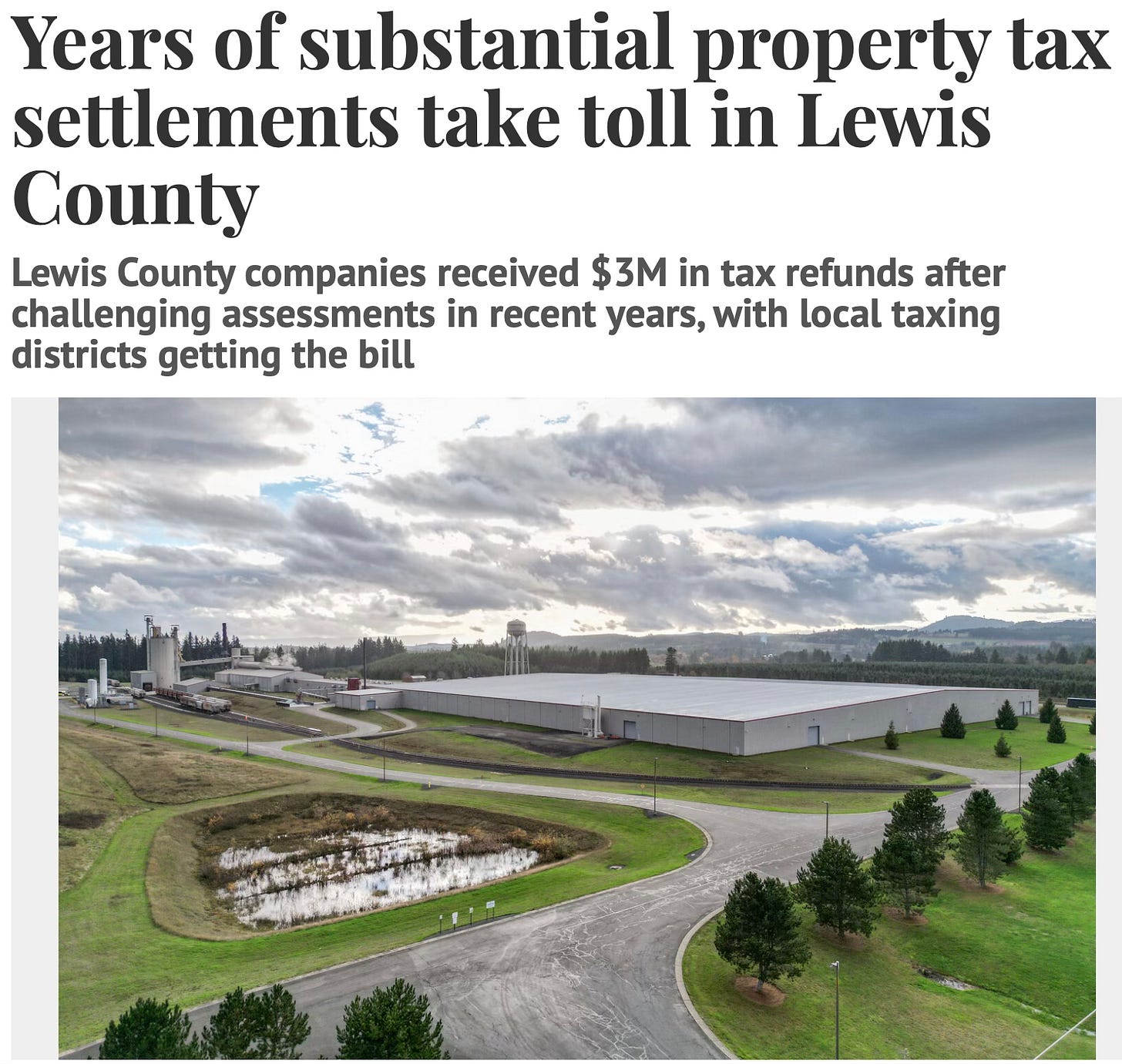

Could Clallam Face Million-Dollar Tax Refunds?

In Lewis County, a legal settlement between the county and Darigold has exposed years of high-stakes property tax disputes. Several major companies — including Sierra Pacific, Hardel, and Cardinal Glass — collectively secured over $3 million in tax refunds, with more cases pending.

These refunds didn’t just drain county coffers; they forced cities, ports, school districts, and fire districts to issue their own refunds — costs that ultimately fall back on ordinary taxpayers.

One settlement alone reduced Darigold’s assessed value by $70 million, triggering more than $1 million in refunds.

Could Clallam County ever face a similar wave of appeals and retroactive payouts if businesses suspect they are being over-assessed? If large employers here ever challenge their valuations, the financial shock waves could easily resemble what Lewis County taxpayers are now grappling with.

Climate Dollars for Tribal Transit — But Not for Everyone

Washington’s Climate Commitment Act (CCA) has driven up costs statewide — especially fuel, where Washington frequently ranks among the most expensive states. But the grant funding it generates is selective.

The Tribal Transit Mobility Grant program is funded 100% by CCA dollars — but is available only to federally recognized tribes. That means non-recognized tribes, such as the Chemakum (largely exterminated and enslaved by the S’Klallam Tribe), are excluded entirely.

Recent awards include:

Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe — two vans for the Jamestown Healing Clinic: $304,150

Makah Tribe — four bus shelters and ADA upgrades: $100,000

Lower Elwha and Quinault received nothing in this cycle.

These grants may serve legitimate transportation needs, but the question remains:

If everyone pays the climate tax, why does only one subset — roughly 1% of the local population — receive these particular benefits?

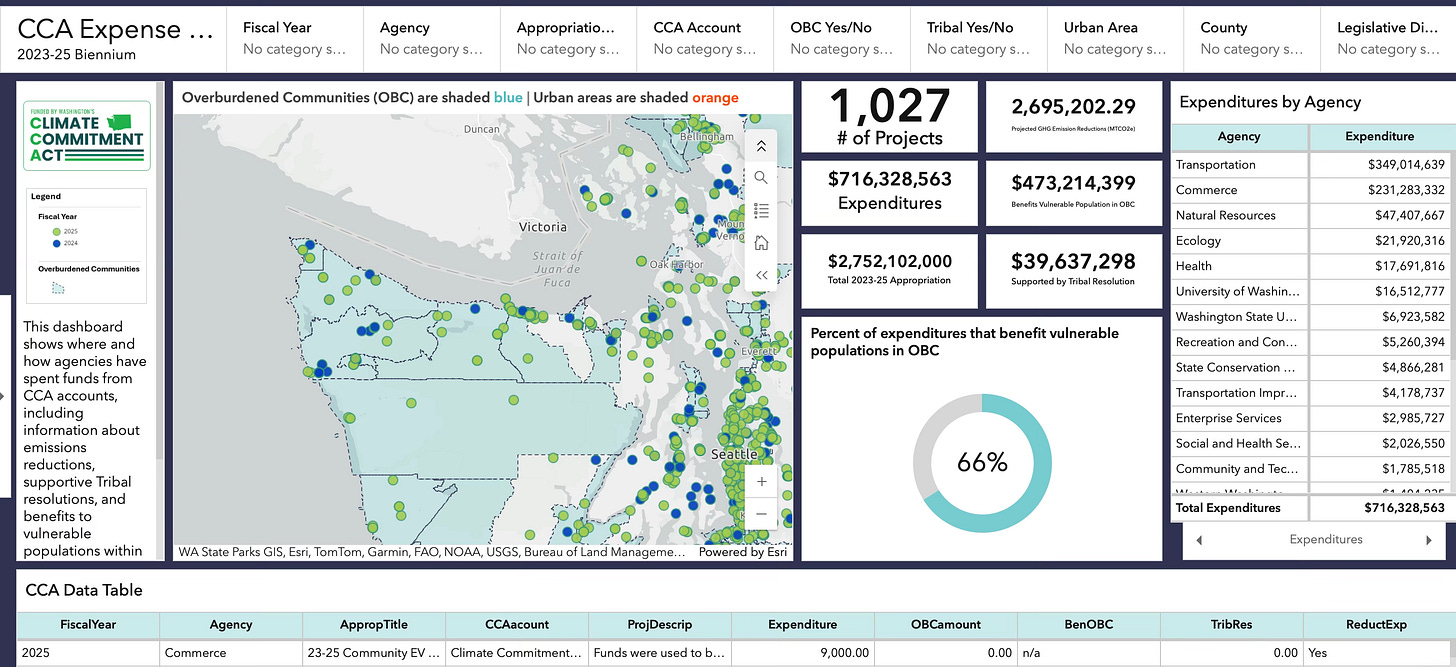

Millions in CCA Spending — But to Whose Benefit?

A new state dashboard now tracks Climate Commitment Act spending. Clallam County has both tribal and non-tribal projects. Sequim shows three projects, while Blyn, headquarters of the Jamestown Tribe, has triple that amount.

Some project descriptions raise eyebrows, such as this $136,566 expenditure for the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe:

“Protect the interests of the tribe while promoting an efficient and just transition to clean energy, clean air, and clean water… largely through added staff capacity and resources.”

Estimated carbon reduction: 0.00.

Every time you pay higher prices — at the pump, at the store, or on your utility bill — remember where your hard-earned money came from, and where it’s going.