Should “Land Back” Be Children’s Curriculum?

Dr. Sarah reads an ideological children's book promoted by our local libraries

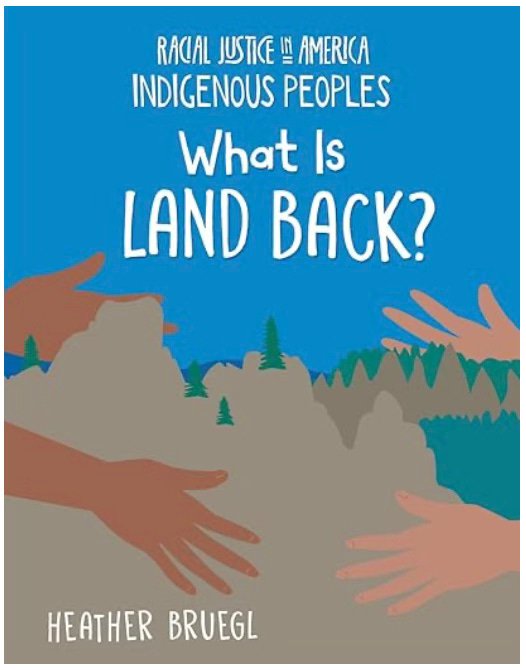

The North Olympic Library System chose to promote a children’s book titled What Is Land Back? during Native American Heritage Month. To see what message the library is promoting to local families, CC Watchdog West End correspondent Dr. Sarah Huling agreed to read the book aloud.

What followed wasn’t the gentle history lesson you might expect from a book marketed to grade-schoolers. Instead, it introduced young readers to political concepts such as dismantling “white supremacy structures,” “defunding systems that enforce oppression,” and returning all public land to tribes.

Dr. Sarah, who holds an EdD in equity, ethics, social justice, and systems governance, offered this reflection:

“In all of human history, oppressing the oppressor has never improved the lives of the oppressed; it only changes who gets hurt.”

These same themes—cycles of harm, trauma, and inherited injustice—run throughout the book. But so does something else: a one-sided telling of history that avoids some of the nation’s most uncomfortable truths.

Below is the deeper look that the library didn’t provide.

What the Book Teaches Kids

What Is Land Back? by Heather Bruegl presents the Land Back Movement as an Indigenous rights and environmental justice cause. In simplified form, the book explains:

Indigenous people see land as “living and breathing,” a spiritual relationship not based on ownership.

Their connection to the land is reciprocal: they are part of it, and it is part of them.

Removal from homelands is described as a trauma unique in its scale and injustice.

European settlers are portrayed as employing bribery, coercion, and threats to secure treaties.

The federal government is described as an agent of dispossession, violence, and deceit.

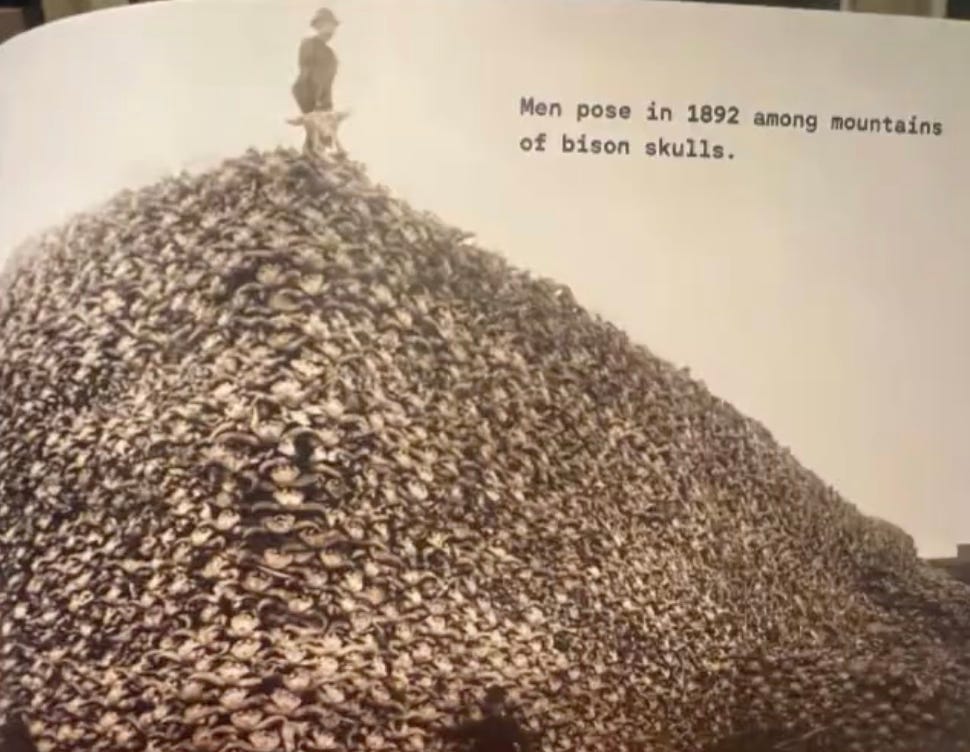

The narrative centers on historical harms committed against tribes—which undeniably occurred. But it omits the full historical pattern of violence and coercion that existed long before the U.S. government arrived.

That omission matters when the goal is educating children.

History on the Olympic Peninsula Was More Complicated Than the Book Suggests

If we are going to talk about “historic injustice,” then we owe children the whole story.

On the Olympic Peninsula, violence cut many directions. Tribes themselves routinely raided, enslaved, and killed neighboring groups:

The 1868 massacre at Dungeness Spit, when S’Klallam warriors killed 17 Tsimshian men, women, and children, looted their belongings, and even turned on their own member, “Lame Jack,” afterward.

Slave raids across the Pacific Northwest were conducted by the S’Klallam, Makah, Hoh, Quileute, and others.

The 1847 joint Suquamish–S’Klallam raid led by Chief Seattle, which destroyed the Chemakum Tribe entirely and enslaved survivors.

The 1808 wreck of the Russian ship Sv. Nikolai, after which survivors were enslaved for nearly two years by local tribes.

These aren’t fringe stories—they are part of the region’s documented historical record.

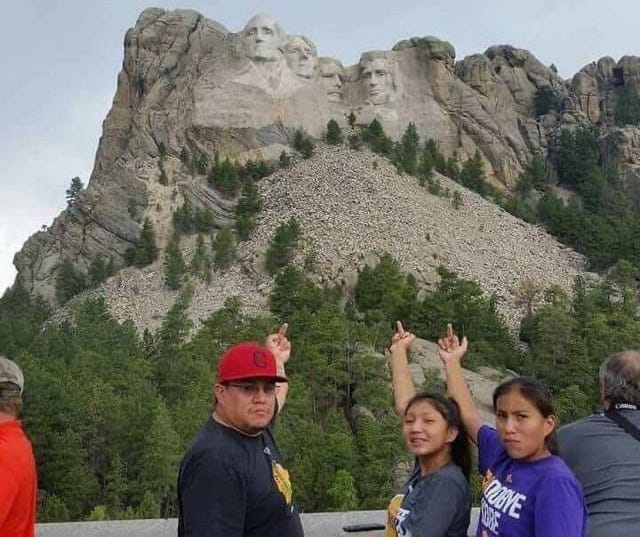

So when the Land Back book tells kids that Mount Rushmore is “stolen land,” or when viral images show people flipping off the monument as a symbol of resistance, the conversation becomes less about reconciliation and more about political symbolism.

Symbolism can divide us. History, taught honestly, helps prevent that.

The book says,

“Indigenous people practice a sustainable relationship with the land. They take only what is needed and replenish any resources that are taken. This connection is something that cannot be broken.

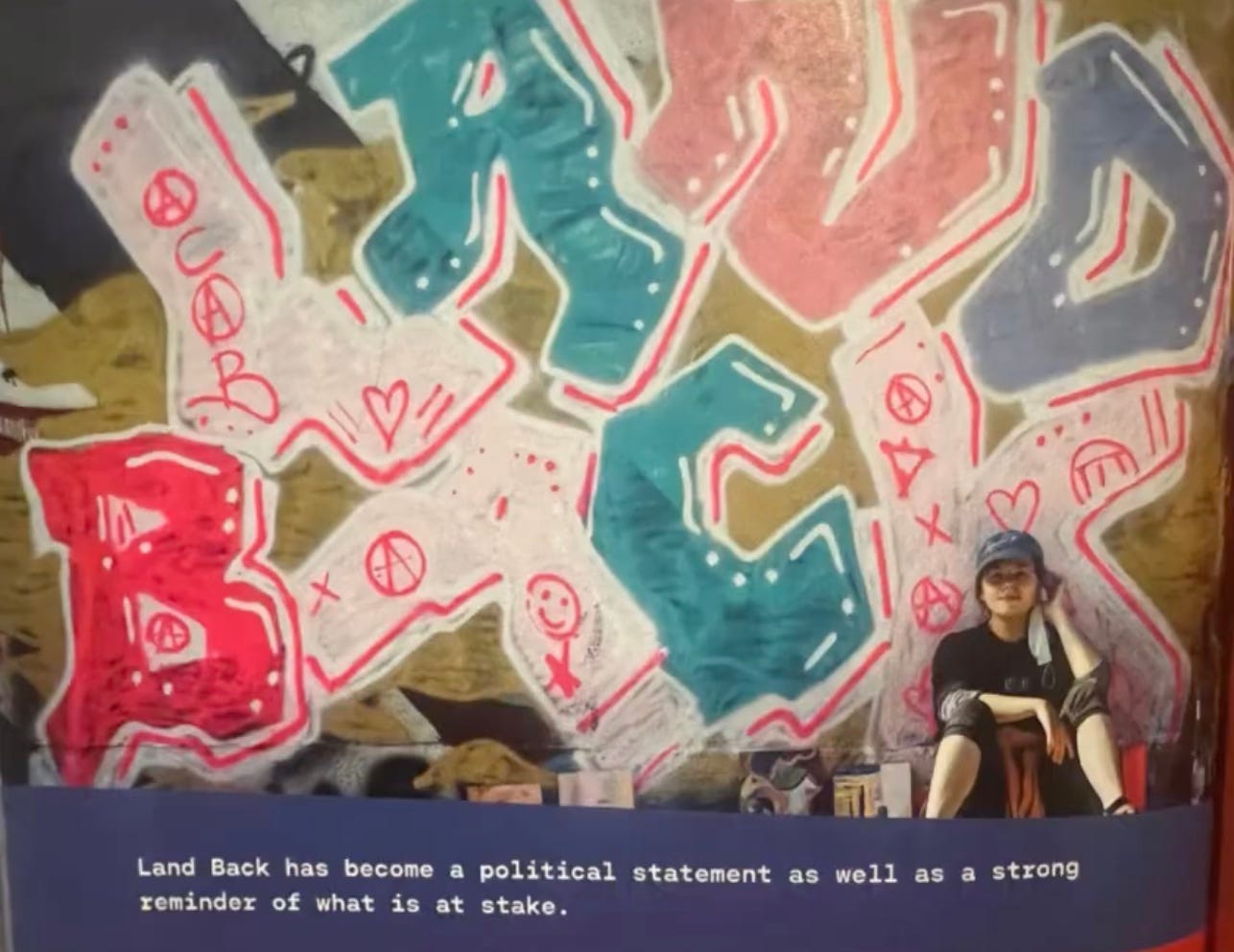

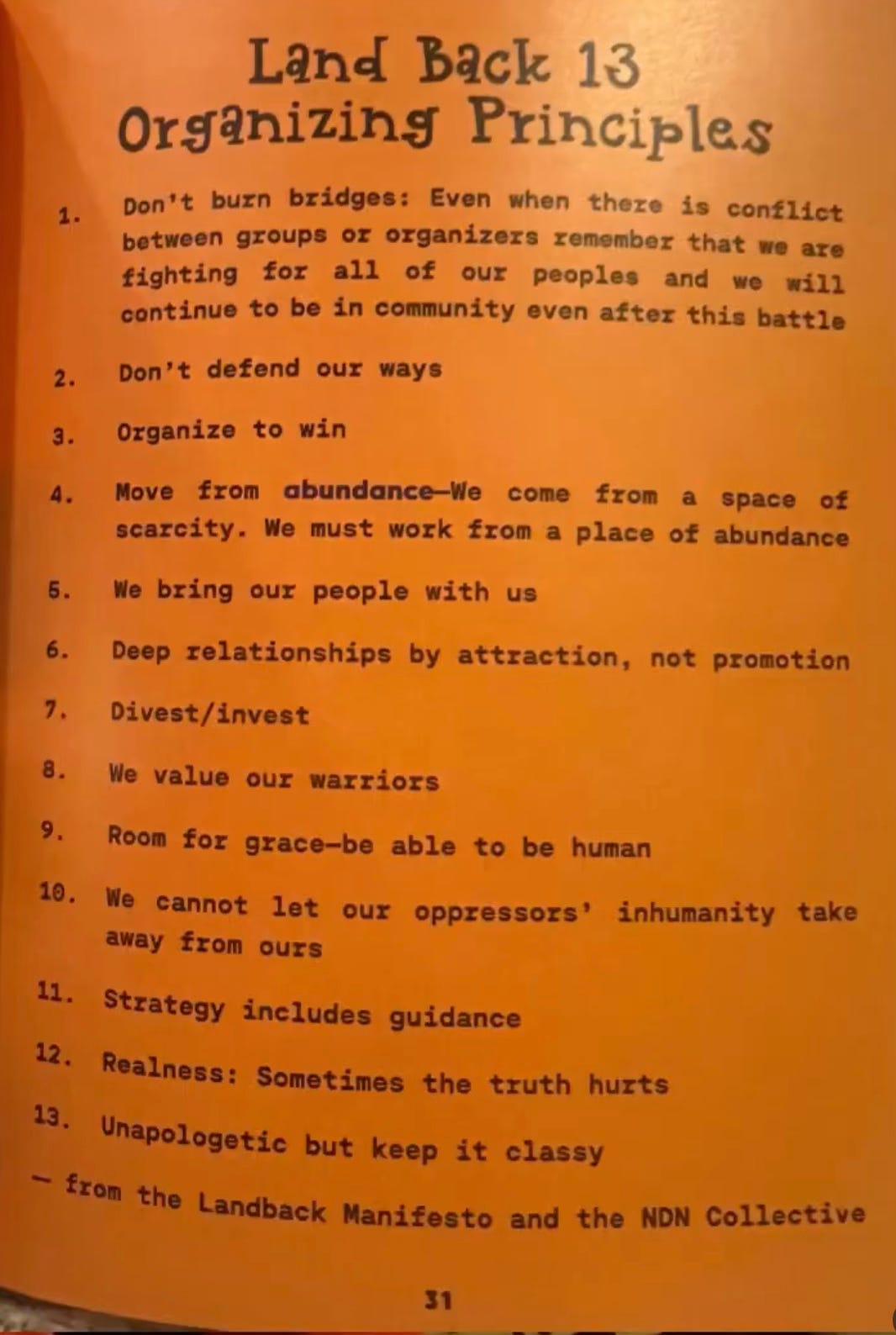

What the Land Back Movement Actually Demands

The book outlines the movement’s four stated goals:

Dismantle “white supremacy structures.”

Defund systems that enforce oppression.

Return all public land to Indigenous people.

Create a new era of policy and governance.

These are not small proposals. They are political goals with sweeping implications—yet they are presented to children as simple moral truths.

The book concludes that past wrongs must be righted and Indigenous people’s connection to the land must be “restored.”

But restored to what—and who decides? Especially in a nation where ancestry is deeply mixed, and where even local tribal leadership reflects that complexity.

We Are a Blended Society—So Why Are We Teaching Kids to Divide Ourselves by Bloodline?

If we are going to tell children that obligations or rights flow from ancestral harm, we must grapple with the reality of modern America:

Most Americans are ethnically blended.

Most tribal members have a majority non-tribal ancestry.

And the clearest local example is Jamestown S’Klallam CEO Ron Allen, who is only 1/4 Jamestown blood quantum—meaning he is 75% non-tribal, descended from a British great-grandfather. His kids are 1/8 Jamestown, and his grandkids would be 94% colonizer.

He is legally and legitimately a tribal leader. He is also, by the book’s framing, 75% colonizer.

So which part of him is responsible for reparations—and which part receives them?

This is the puzzle we hand our children when we teach history through the lens of inherited guilt rather than shared citizenship.

Dr. Sarah: Why She Could Hold This Conversation Responsibly

Here is the story Dr. Sarah wanted readers to understand—why she, of all people, could read this book with both compassion and critical clarity:

I’ve spent over twenty years in rural healthcare and, more recently, in governance, living close to the ground where history, land, and systems collide. I didn’t go back to school to collect degrees. I went back because I kept asking why systems continue to produce the same harms,regardless of who’s in charge.

I originally went back to school to earn an MBA in Rural Healthcare, thinking that if I could understand the financial and operational side of rural medicine, I could help fix the structural pressures hurting patients and their small communities. But the deeper I got, the clearer it became:

Our problems weren’t only financial; they were structural, ethical, historical, and systemic. The MBA answered the “how,” but not the “why.” It showed me the mechanics of the system but also revealed that the system itself was built on foundations that created inequity in the first place. That insight propelled me into the next chapter: earning an EdD in Educational Leadership (not a PhD), with an emphasis on equity, ethics, social justice, systems thinking, and community governance.

My work centers on understanding: How trauma cycles repeat, how inequity is created and recreated, how power structures shape rural life, and why good intentions can still produce damaging systems.

And on why she approached the children’s book the way she did:

No society has ever healed by harming the people who once harmed them. The cycle only breaks when we address the conditions that allowed the harm to take root in the first place, not by recreating it with new actors.

Land rights and sovereignty are legitimate, deeply rooted issues, but when the remedy risks creating new inequities today based on ancestry, we inadvertently recreate the very patterns of exclusion we’re trying to end. Historical correction cannot become present-day inversion.

Her approach—warm, honest, a little snarky—kept the conversation grounded rather than inflammatory.

The Real Question for Our Community

NOLS is free to highlight books that explore Indigenous history. Real history deserves real discussion.

But should a publicly funded library be introducing children to political movements that demand the return of all public land, the dismantling of “white supremacy structures,” and the defunding of modern institutions?

Should we be teaching kids that:

guilt is inherited,

oppression is racialized,

and divisions of the past must be maintained in the present?

Or should we teach them that no child owes a debt for harms they did not commit, and no child is owed payment from people who never harmed them?

Our children deserve nuance, not ideology.

And our community deserves transparency about what its institutions are promoting in the name of education.

The United States of America. We now include approximately 330 million people. All these people are included in a mixed collection of races, historical origins, and beliefs. We would like to believe we are strong because we are inclusive with our new residents. We have a Constitution, a representative Congress, and a system of checks and balances. We should believe we are flexible enough to modify our laws to benefit the entire population, not just a limited percentage. If the nation teaches their young that a united country is beneficial we all gain. If we teach a division based on early residency we lose our desired unity. Continue to support a United States of America.

Thank you for taking the time to watch and read.

My intent in doing the read-aloud was not to promote Land Back, but to give our community a clear look at what’s being presented to children and to ask whether it’s balanced, truthful, and age-appropriate.

I’m grateful for anyone willing to wrestle with that question in good faith.