In the latest issue of Clallam Democrats Rising, Commissioner Mike French highlights what he calls a banner year of accomplishments. But behind the celebratory tone are delayed projects, rebids, modest workforce outcomes, and housing models that raise serious questions about cost and priorities. If 2025 was a year of “progress,” the public deserves a clearer accounting of what that progress has actually delivered.

French’s 2025 Highlight Reel — And What It Leaves Out

Commissioner Mike French recently touted several major initiatives as evidence of strong leadership and forward momentum, but they deserve a closer look.

$6 Million Through the Opportunity Fund

French points to $6 million invested in infrastructure and economic development through the Opportunity Fund.

One of the largest allocations: $800,000 to Habitat for Humanity of Clallam County for its Carlsborg development.

That award followed a six-month delay after questions surfaced about public bidding compliance. Habitat ultimately agreed to bring the project into compliance — but the delay itself raised a broader concern:

What happens to public oversight once tax dollars move into private NGOs?

When nonprofits receive substantial public funding, transparency expectations should increase — not decrease.

A New Role, An Old Question

Habitat for Humanity of Clallam County became the only affiliate in the nation to hire a Native American Housing Liaison, funded by public grant dollars and following a $50,000 donation from the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe.

Habitat maintains the role is not tied to tribal preference. Yet repeated public requests for the job description have gone unanswered.

In an era where government agencies are expected to disclose even minor details, the silence from a publicly funded nonprofit is difficult to reconcile.

Meanwhile, the Carlsborg development remains idle more than a year later. If nearly a million dollars in public funds cannot move dirt faster than the private sector, it is fair to ask whether this is effective economic development — or bureaucratic stagnation.

Joint Public Safety Facility — Still Not Breaking Ground

French also cites progress on the Joint Public Safety Facility, a roughly $22 million project intended to house:

The Sheriff’s Office Emergency Management division

The regional 911 dispatch center (PenCom)

Completion was projected for 2026.

However, earlier this year, all three construction bids were rejected after issues emerged involving the electrical subcontractor’s scope and pricing. The project was sent back out to bid.

That means:

No construction start yet

No revised completion date

Additional delay and administrative cost

Rebidding may have been legally prudent — but it also underscores a pattern: major initiatives announced, then slowed by procedural breakdowns.

For a project centered on public safety, timeliness matters.

“Affordable Housing” — For Whom?

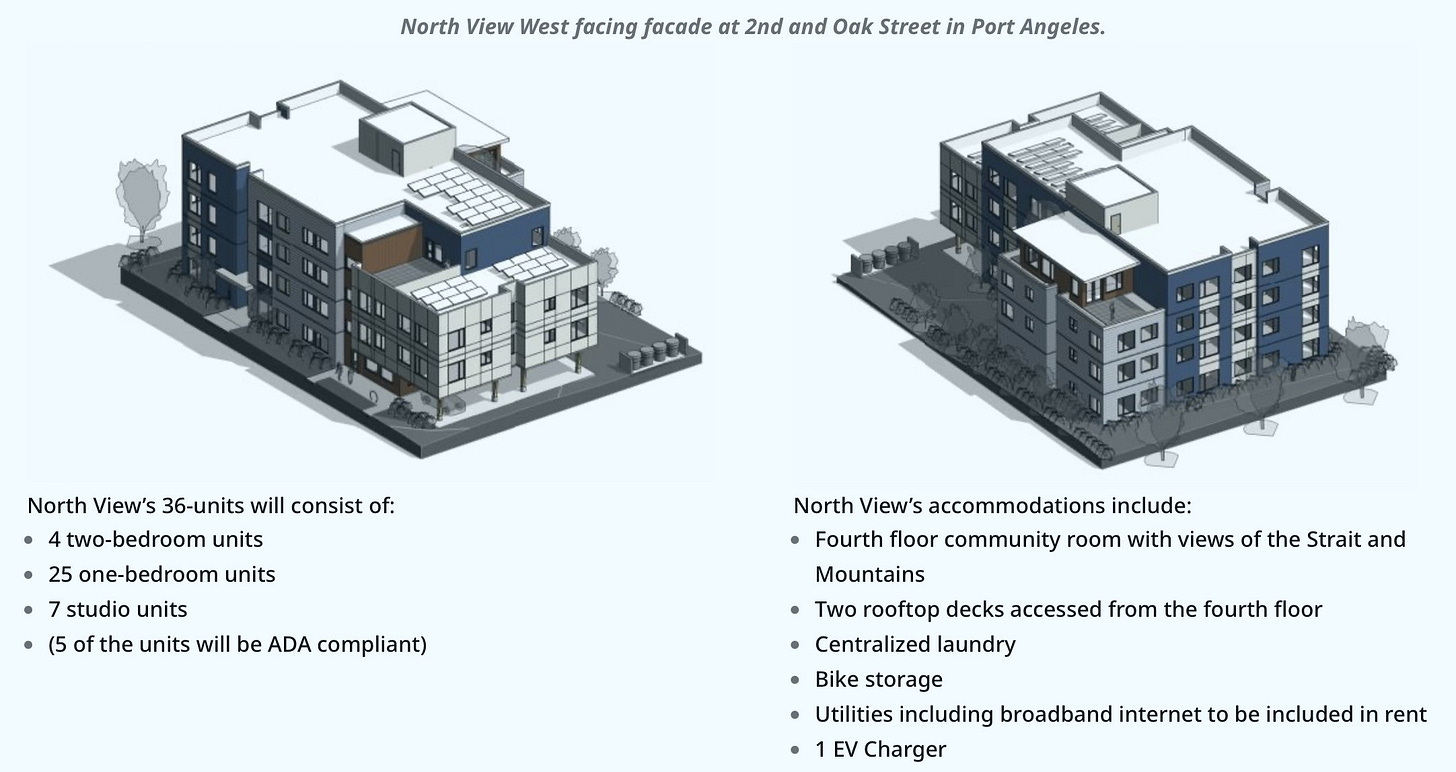

French highlights investment in affordable housing, including a 36-unit apartment building near downtown Port Angeles — North View, developed by Peninsula Behavioral Health.

Key details:

Approximate cost: $350,000 per unit

Total investment: roughly $12.75 million

Permanent supportive housing model

Units prioritized for individuals with frequent incarceration histories

Described as “not exclusively dry” meaning drug and alcohol use will be tolerated

Amenities include rooftop terraces, harbor views, dishwashers, air conditioning, dog washing facilities, and EV chargers.

With more than 4,000 people reportedly awaiting housing in Clallam County, scaling this model county-wide would require well over $1.5 billion at current per-unit costs.

The question isn’t whether supportive housing has a place. It’s whether this model — at this price point — is the most effective use of limited public dollars.

Affordable for whom? Certainly not for taxpayers underwriting it.

Recompete: $35 Million, 31 Jobs

French celebrates coordination in the regional Recompete initiative — a five-year, $35 million federal grant intended to bring people back into the workforce.

Year One results (October 2024 – September 2025):

208 prime-age individuals enrolled

117 enrolled in training

84 completed training

31 placed into jobs (21 prime-age)

French has publicly stated the goal is to transition around 900 people into good jobs over five years.

At 31 placements in Year One, the program is significantly behind that pace.

If you divide $35 million by 900 jobs, that equates to roughly $38,000 per job placement — assuming targets are met.

Year One analysis shows:

Modest enrollment relative to regional need

Conversion rates from training to placement around 26–27%

Wraparound services relying heavily on outside partners

Employer engagement not yet translating into sustained hiring pipelines

The report itself frames Year One as a startup phase. That may be true — but public dollars are being spent in real time.

There is a growing perception that Recompete is evolving into another public aid framework layered with workforce language, rather than a lean job-placement engine.

The Recompete Coordinator: Local Investment or Outsourced Leadership?

The County’s Recompete Plan Coordinator position, which works for the Board of Commissioners, went to Molly Pringle.

According to Facebook, Pringle is a resident of Portland, Oregon.

On LinkedIn, she describes her work as:

Building “authentic relationships”

Co-creating infrastructure and strategic plans

Redistributing power and resources

Shining a light on “white supremacy and capitalism”

Her background is rooted in nonprofit grant writing and equity-focused organizational work.

That approach may appeal in some circles. But when you’re talking about a $35 million economic recovery effort, most taxpayers are looking for something pretty straightforward:

More people in real jobs

Local businesses growing

Higher wages

Strong partnerships with employers here at home

When the language around a workforce program starts sounding more ideological than economic, it raises fair questions about priorities.

Is the focus getting people back to work and strengthening the local economy? Or is it fighting white supremacy and capitalism?

With this much public money involved, the mission shouldn’t be hard to understand.

A Pattern Emerging

Across French’s highlighted accomplishments, a pattern appears:

Large public expenditures

Heavy NGO involvement

Delays and rebids

Modest measurable outcomes

Messaging ahead of results

That does not mean every initiative will fail. But it does mean the celebration may be premature.

What Should Change in 2026

Commissioner French still has time to recalibrate.

If 2026 is to be a genuine success year, priorities should include:

Demanding measurable performance benchmarks for Recompete tied directly to job placements.

Accelerating shovel-ready infrastructure projects without procedural breakdowns.

Increaseing transparency requirements for NGOs receiving public funds.

Prioritizing housing models that maximize units per dollar spent.

Focusing relentlessly on economic output, not ideological framing.

Clallam County does not lack vision statements. It lacks timely, scalable results.

There is still opportunity for success. But it will require shifting from announcements to outcomes — from ribbon-cutting projections to job placement realities.

Celebrating 2025 is easy. Delivering in 2026 will be harder.

The voters will notice the difference.