At a recent City Council meeting, Port Angeles unveiled its 20-year Comprehensive Plan—but tucked into the late-night discussion was a surprise proposal to replace standard tribal consultation with the international doctrine of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC), which would give sovereign nations the power to approve or veto city projects. FPIC is a U.N. standard designed for major industrial projects in developing countries, not local zoning or housing decisions, and no other city in Washington uses it. With Port Angeles already struggling with housing and infrastructure challenges, residents deserve transparency before such a sweeping change is adopted.

A 20-Year Blueprint for Port Angeles

On November 18, the City of Port Angeles presented its draft Comprehensive Plan—the document that will guide all major city decisions for two decades. The plan covers:

Housing access, affordability, and equity

Economic development

Land-use and zoning changes

Utilities and infrastructure

Parks and recreation

Environmental protection and climate resiliency

Transportation systems

Neighborhood services

It’s a consequential document—one that affects every resident and business in the city.

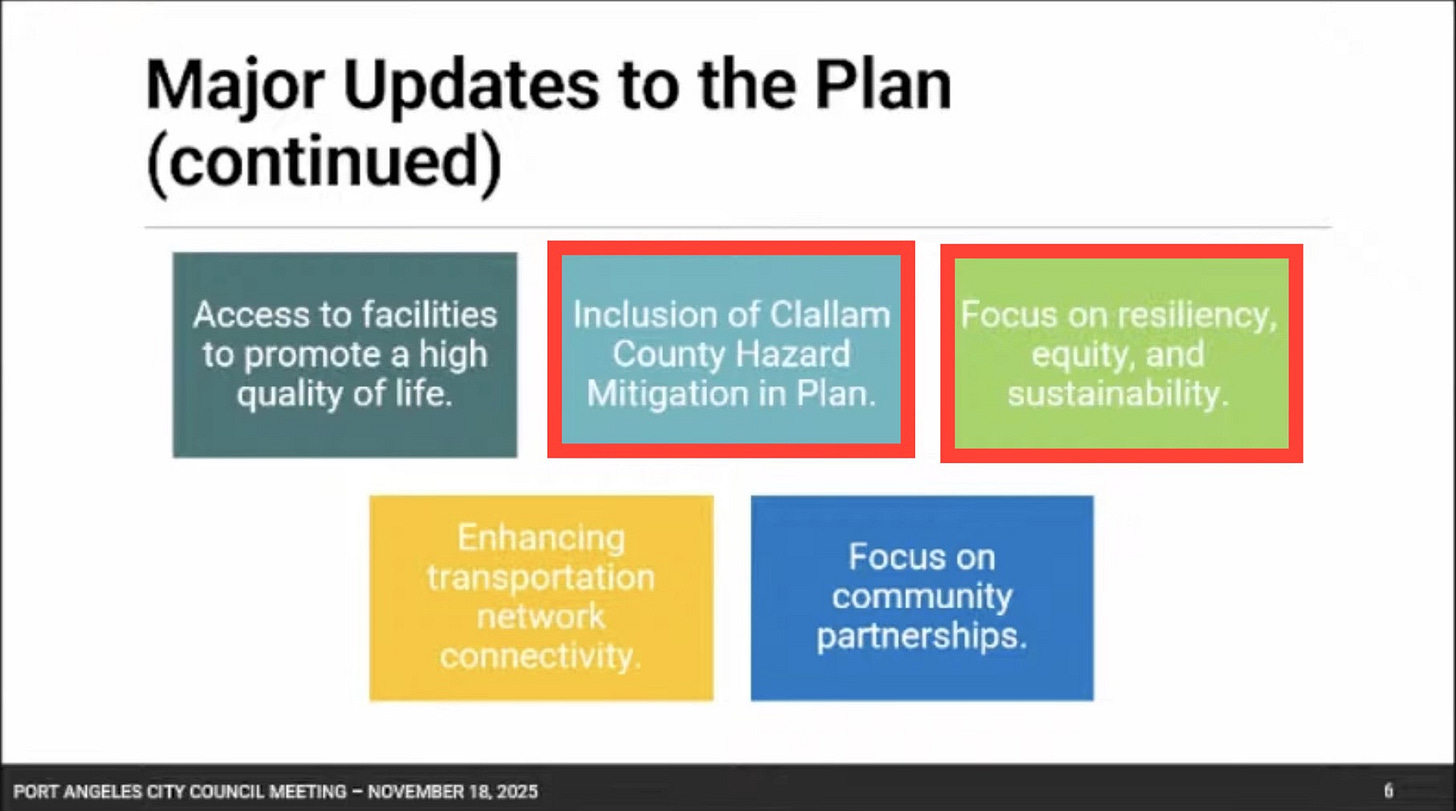

The latest draft emphasizes “equity,” “sustainability,” and “resiliency,” and incorporates the County’s Hazard Mitigation Plan, currently being drafted behind closed doors by the North Olympic Development Council (NODC), an unelected nonprofit headed by its president, County Commissioner Mark Ozias and and its secretary, Port Angeles City Councilmember Navarra Carr.

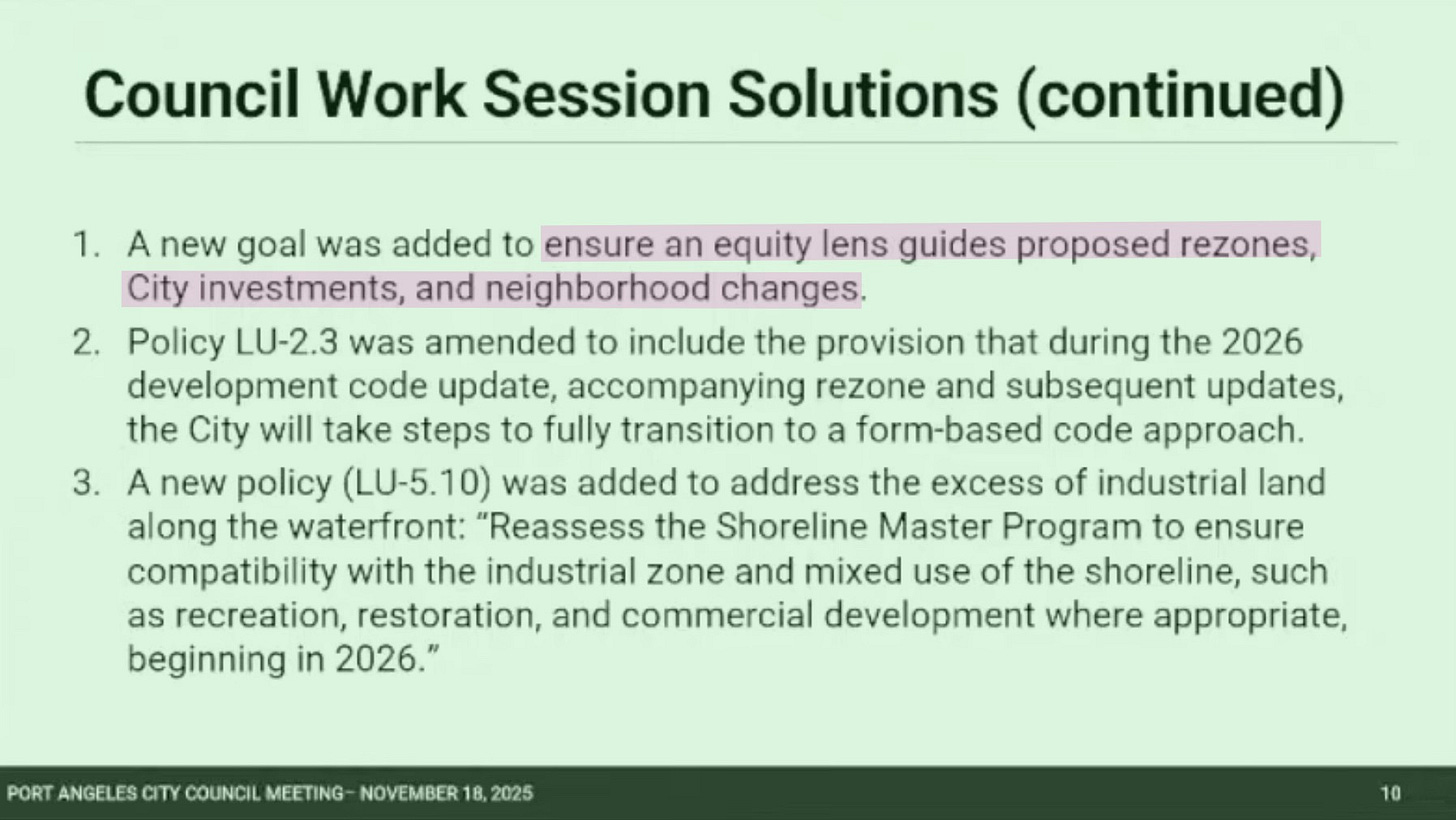

City Councilmembers have added yet another new policy goal:

“To ensure an equity lens guides proposed rezones, City investments, and neighborhood changes.”

Whether residents agree on that framework or not, at least these changes appeared in the public packet.

What came next did not.

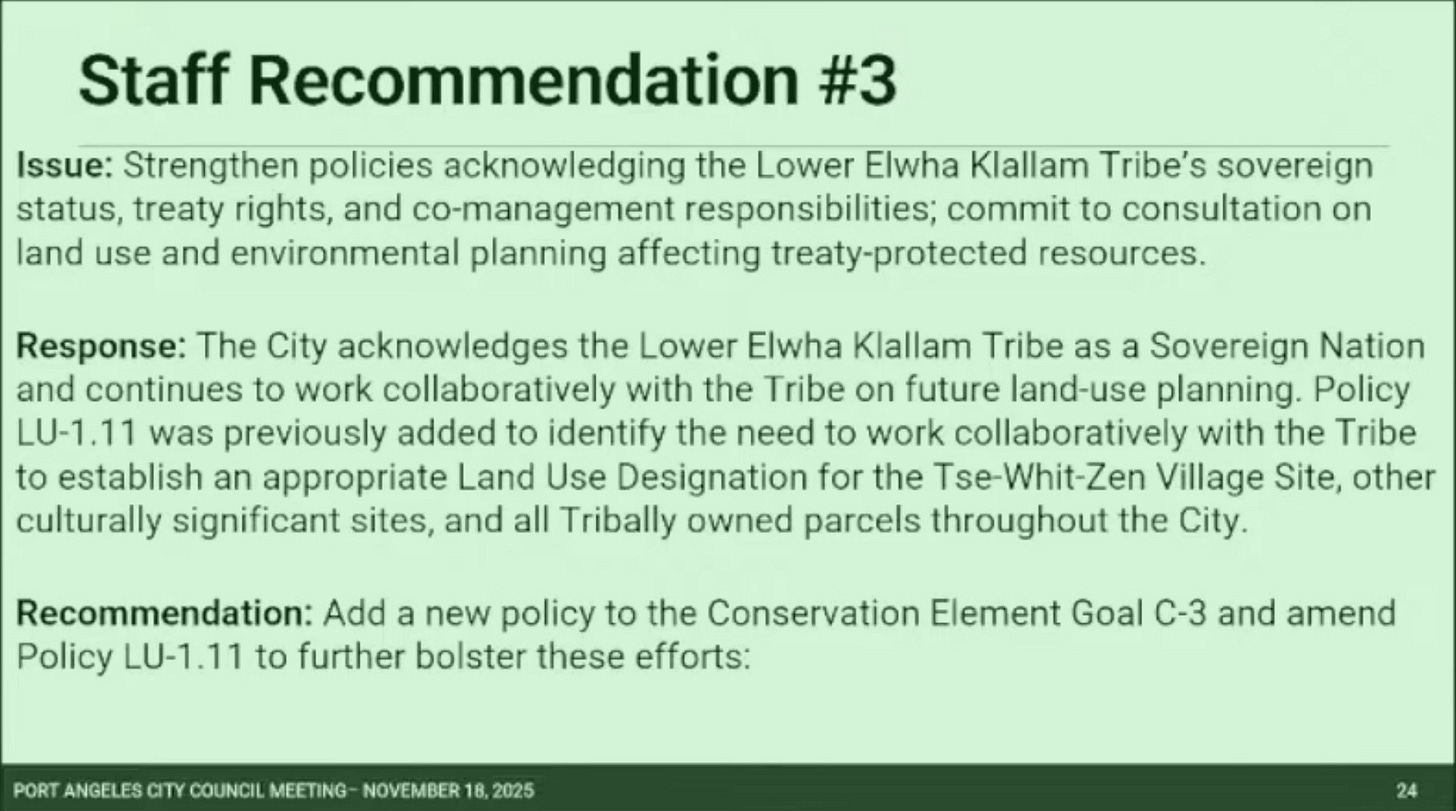

A New Push: Expanded Tribal Authority Over City Decisions

City leaders mentioned a perceived need to strengthen language acknowledging the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe’s sovereignty, treaty rights, and co-management responsibilities. The city responded that it already collaborates regularly with the Tribe. Fair enough—cooperation is part of daily governance here.

But Councilmember Lindsey Schromen-Wawrin—now in his final month in office—pushed for something dramatically different.

He proposed replacing all “consultation” language with Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)—a sweeping international legal standard that goes far beyond anything currently required under Washington law, the Centennial Accord, or federal Indian law.

Schromen-Wawrin’s Proposals

1. Replace “No Net Loss” With “Net Ecological Gain”

He argued the city should adopt “net ecological gain” instead of the longstanding environmental standard of “no net loss.”

This sounds noble, but it is vague, untested, and could make future development—housing, remodeling, small business projects—nearly impossible to approve without proving a positive ecological improvement.

What does “gain” even mean in a small urban environment? This policy creates more questions than answers.

2. Replace Tribal Consultation With the FPIC Doctrine

This is the more alarming shift.

Instead of standard local-to-tribal engagement, FPIC requires:

Tribal consent before a project moves forward, not consultation

No deadlines or time limits

Full documentation, in the tribe’s language

The right for the tribe to say yes, no, or reverse its decision

Binding legal agreements, grievance procedures, and compensation systems

Deference to tribal timelines, lawyers, and independent experts

Stoppage of projects until consent is obtained

FPIC is designed for mining, dams, oil extraction, and major infrastructure in developing nations. It has never been applied to municipal planning, city rezones, or individual property permits in Washington State.

A local realtor shared a story during public comment: a client on Cassidy Road was told they could not remove a tree because the Jamestown Tribe said it had cultural significance. If that’s happening now, imagine what would happen if FPIC were codified.

This is not a small tweak.

This is a profound legal shift.

Why This Matters

FPIC effectively grants sovereign authority over municipal decisions to another sovereign nation. Again—sovereignty is real, and tribal governments have legitimate rights and long-standing treaty protections. But Port Angeles is a municipal corporation under Washington State law, not the United Nations.

If Port Angeles adopted FPIC, it would create:

A new veto point over zoning, utilities, stormwater, transportation, and permitting

Unclear enforcement mechanisms

Longer timelines for housing approvals

Higher administrative costs

Legal ambiguity that courts would likely have to resolve

A regulatory environment that no other city in Washington has

Imagine if Port Angeles extended this same power to other sovereign nations such as Canada, Japan, Russia, or China. No one would tolerate that. Yet FPIC imports that same model of authority—except selectively, and without any democratic process.

So the question becomes: Whom is Councilmember Schromen-Wawrin representing? Port Angeles residents—or another sovereign government that already has its own representation?

The FPIC Manual: What’s Actually Inside

The FPIC manual referenced in the discussion is a 50-page U.N. guidance document for project managers supervising development in remote Indigenous communities. The assumptions within it:

The national government is powerful.

The Indigenous community is vulnerable.

The project is extractive or highly disruptive.

The Indigenous nation has absolute authority to grant or withhold approval.

Nothing in the manual expects FPIC to apply to:

Municipal zoning

Housing

Sidewalk improvements

Tree removal

Sewer upgrades

Local utility maintenance

Applying FPIC to a city like Port Angeles would be unprecedented—and likely unworkable.

Transparency Matters—And This Needs Sunlight

This proposal surfaced late at night, at the end of a long meeting, without staff analysis, legal review, public engagement, or even a plain-language explanation.

Residents should not learn about international legal doctrines being inserted into city code by accident.

Whether you support or oppose FPIC, this deserves an open, honest, and informed debate—not quiet insertion into a 20-year planning document.

Call to Action

Councilmember LaTrisha Suggs backed the proposed changes, saying, “I think it’s important that we set the standard—this is a 20-year document.” Suggs currently works for the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe as a Restoration Planner and previously served as Assistant Director of the Elwha River Restoration Office for the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe—experience that may shape her perspective on these issues.

No councilmembers voiced any opposition to Councilmember Schromen-Wawrin’s push to insert “net ecological gain” and FPIC into the Comprehensive Plan.

City staff have now been directed to incorporate the new language into the draft, which is scheduled to return for review on December 16.

The full City Council can be reached at council@cityofpa.us.

They meet tonight at 6 p.m., and public comment is allowed.

Click here for information on attending in person or online.

This is your opportunity to speak up before these sweeping changes are quietly embedded into the City’s 20-year roadmap.

Port Angeles deserves transparency.

Port Angeles deserves open debate.

And Port Angeles deserves a future shaped by its residents—not by legal doctrines introduced without public awareness.