The Clallam Conservation District wants to charge every property owner a $5 parcel fee, claiming it’s to support conservation. But behind the scenes, the agency is piping ditches that recharge wells, exempting powerful landowners, partnering with tribal entities expanding into the water utility business, and sidestepping public transparency. All this comes after the County cut their funding—following years of reckless spending on poetry programs and perks. Now they want you to pay the price. Is this really about conservation—or quiet control over the region’s water supply?

Tomorrow, the Clallam Conservation District (CCD) will consider implementing a $5 per parcel fee to help fund its operations. On the surface, it may sound like a minor ask—just a few dollars to support soil testing, native plant sales, and water quality programs. But dig a little deeper, and you’ll find a much more complex and far-reaching issue. This isn’t just about funding conservation work. It’s about who controls our water, how decisions are made, and whether the public is being asked to foot the bill for consequences they never agreed to.

A quiet shift in water management—and its consequences

For years, the CCD has worked with the City of Sequim, Clallam County, and the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe to pipe historic irrigation ditches across the east county. These efforts are framed as modernizing infrastructure and improving efficiency, but they’ve raised serious concerns among residents.

The U.S. Geological Survey has clearly stated that leakage from these open irrigation ditches is the region’s most important source of groundwater recharge. Removing them leads to measurable declines in groundwater—potentially up to 20 feet over time—which could leave hundreds of wells dry. For property owners in Agnew, Dungeness, and parts of Sequim, that’s not just a water issue—it’s a property rights issue, a financial issue, and a quality-of-life issue.

“Analysis using the model shows that leakage from irrigation ditches is the area 's most important source of ground-water recharge. Termination of the irrigation system would lead to lower heads throughout the ground-water system. After 10-20 years of no irrigation, the water-table aquifer would have average drawdowns of about 20 feet and some areas would become completely unsaturated. Several hundred wells could be in danger of going dry. If irrigation were terminated, leakage from the Dungeness River would become the major source of ground-water recharge.” — USGS report

Who benefits—and who’s exempt?

These water shifts raise broader questions about equity and sovereignty. As private landowners face well monitoring, potential drawdowns, and parcel fees, tribal properties placed into trust status are exempt from many of these requirements. At the same time, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe—a close partner in the CCD’s ditch-piping and water initiatives—is actively moving into the water utility business.

Their ability to maintain consistent irrigation, including for their 122-acre golf course, stands in sharp contrast to the restrictions many rural residents face.

This is not a criticism of tribal governance—but it does raise fair questions about consistent policy, fairness, and long-term access to water across Clallam County.

Under the Dungeness Water Rule—established by the Department of Ecology in 2013—the CCD is the agency responsible for monitoring water use from private wells in the Sequim-Dungeness watershed. While CCD stresses this monitoring is “only for data collection,” the presence of meters has made many homeowners uneasy, especially as water access becomes more politically and environmentally charged.

Transparency, accountability, and the $5 fee

Clallam Conservation District Manager Kim Williams has described the fee as a necessary step to maintain services in light of reduced county funding and growing administrative burdens—such as rising legal costs and an increase in public records requests. But some residents argue those record requests are a symptom of a deeper issue: a lack of transparency.

The CCD does not livestream or archive its public meetings. Minutes are often sparse. And many feel the agency hasn’t done enough to clearly communicate the long-term impacts of piping projects—especially for those relying on shallow wells.

Documents from the District’s own files tell a more complicated story than what is often shared publicly. A 2017 mitigation agreement, for instance, acknowledged that a pipeline project would reduce groundwater recharge over four miles away—yet only one powerful landowner received a special infiltration system to offset the impact. Nearby residents relying on private wells received no such assistance, and most were never even informed.

Community concerns growing

Comments made by CCD Supervisor Lori DeLorm at a public meeting added further confusion. Some residents recall her stating that the Tribe has a “treaty right to water,” and that the CCD’s mission is to “protect salmon.” Yet the Tribe’s recognized treaty rights pertain to fishing, not explicitly to groundwater or irrigation infrastructure. While salmon conservation is certainly a shared value, it’s not clear that the CCD’s statutory mission includes this kind of enforcement role.

The CCD also earmarked $5,000 in taxpayer money for DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) training—even while some residents say their calls about water issues go unanswered, and their properties may be at risk from unpermitted ditch projects. These priorities may reflect good intentions, but they’re hard to reconcile with residents who feel increasingly unheard.

A pattern of overreach?

In recent years, the CCD has also partnered in other controversial projects, including:

The Towne Road realignment, which ran millions over budget and raised safety concerns

The Meadowbrook Creek restoration, which many say worsened flooding on 3 Crabs Road

The Off-Channel Reservoir, a large above-ground structure being built atop earthquake fault lines, still without a clear long-term funding or operational plan

Together, these projects have led many to question whether the CCD has strayed from its original mission of supporting local farmers and landowners—venturing instead into politically charged initiatives and advocacy that increasingly reflect the priorities of special interests rather than the broader community.

What’s fair—and what’s next?

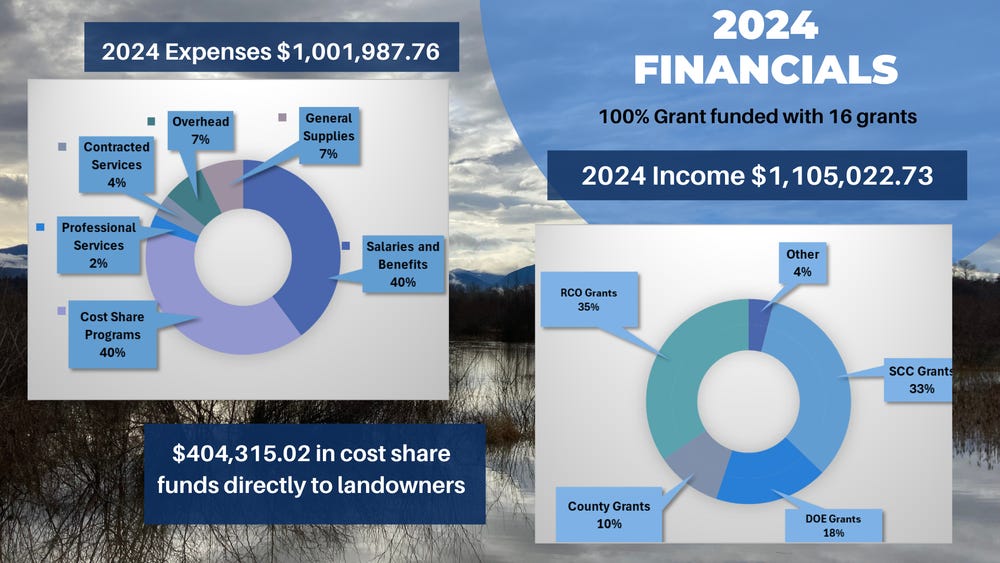

The CCD’s $5 parcel fee would apply to nearly all county residents, including those who don’t farm and may never use the agency’s services. Meanwhile, the District has stated that this fee would help them secure more grants—not reduce reliance on them. That’s a critical distinction: a fee that perpetuates grant dependency without addressing underlying structural issues may not be the best long-term solution.

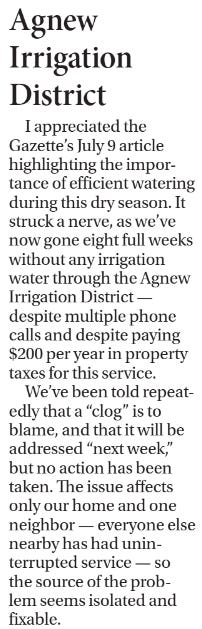

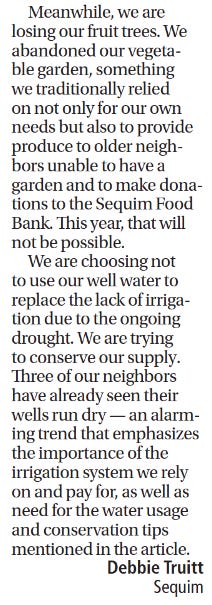

Some residents are also questioning the practical outcomes of ditch piping, citing real-world examples: one letter to the Sequim Gazette editor described a local irrigation blockage that left a family without water for eight weeks during peak season—while their fruit trees withered and their community food donations vanished. Blockages in piped systems are harder to locate and fix. Open ditches, while less efficient, are visible and recharge aquifers naturally. The letter mentions that three area wells have already gone dry.

Passing the buck: when poor budgeting becomes your bill

It’s worth noting that the Clallam Conservation District’s push for this fee comes after funding was cut by the Clallam County Board of Commissioners—a board that has faced growing criticism for reckless and inconsistent spending priorities.

Over the past few years, the County has allocated taxpayer dollars toward non-essential programs like a county poet laureate and has continued funding weekly pizza parties tied to drug outreach programs—even as core infrastructure and public services face budget shortfalls.

Now, instead of reevaluating those decisions, the CCD is left trying to close the funding gap with a mandatory fee on property owners—a workaround that shifts responsibility away from the people who created the problem in the first place.

This pattern raises a larger concern: elected officials and partner agencies are turning to homeowners as an ATM—offering new fees, not because they’re the best solution, but because they’re the easiest to impose. It avoids tough conversations about budget reform and shifts the financial burden to residents already facing rising property costs and dwindling rural services.

A public hearing worth attending

The CCD may be sincere in its efforts to protect water quality and support agriculture. But sincerity doesn’t equal accountability—and transparency must come first, especially when public funds are on the table.

The public hearing on this proposed fee is an opportunity to ask important questions:

Why aren’t these services being funded through voluntary participation or cost-recovery from direct beneficiaries?

Why are private well users being monitored while large, exempt properties are not?

What protections are in place for landowners impacted by ditch piping?

And perhaps most importantly—what is the long-term vision for water control in Clallam County, and who is shaping it?

This is not just about a small annual charge. It’s about property rights, public trust, and whether decisions that affect thousands of residents are being made in an open and equitable way.

Attend the hearing. Ask the hard questions. And make sure this fee doesn’t become just one more way to shift control without public consent.

Friday July 25, 2025, from 5:00 PM to 6:30 PM at the

Red Lion Hotel Port Angeles Harbor, 221 North Lincoln Street in the Juan de Fuca room.

CCD threatens to remove “angry mob”

Trancript from a CCD meeting held 6/3/25. CCD Board Auditor Wendy Rae Johnson:

“. . .from the Tozzer masses during our election, and I am unwilling to be abused at a public hearing. So I think that there is going to be a necessity, because undoubtedly, Mr. Tozzer will get this out to his angry mob, and, um, I feel like it will be very important to have a code of conduct announced of what will be tolerated. Because what was, the way the staff here was treated, when people were coming to get their ballots, was completely unacceptable. You know, it was a public disgrace. And I will not condone any of that.

So, and we know, at the beginning of, I was just at the DNR [?] meeting today, and they have a code of conduct that they repeat at the beginning of every meeting as to what is and what is not allowed. Okay? So, that being said, I think it will be really important because I am so disappointed in the hostility and the rage over nothing -- over mis and dis-information. Not even knowing what they were getting a ballot for and being so mean and angry.

[Director Williams interject: not knowing who they were voting for and why they were voting]

So I think that because that has happened and recently, I think we need to be prepared and have a code of conduct that we announce at the beginning.

[Williams interject: and have strict guidelines] Yeah, and, you know, people will know that we can ask that people to be removed. Okay?”