Should working-class residents in Clallam County continue paying for the sins of generations past? As Commissioner Mark Ozias reads yearly proclamations about colonization and equity, he also leads an NGO steering millions in taxpayer-funded grants—many going to tribal entities with deep political influence and millions in annual revenue. The growing web of money, power, and ideological reparations in Clallam County has been exposed—and it’s time to ask the question our leaders won’t: When will this debt be paid?

In a 2019 Slate interview, Kerri Rawson shared the unimaginable: her father—Dennis Rader—was the BTK killer, responsible for the torture and murder of ten people. “You love your dad,” she said, “and then you find out he’s murdered ten people. How do you live with that?”

Rawson did not know. She did not help him. She did not excuse his crimes. Yet she has lived under a cloud of guilt and suspicion, simply because of who her father was. The question at the heart of her story is as old as justice itself: Should someone be held accountable for something they didn’t do—just because of who they’re related to?

The politics of proclamation

Each October, County Commissioner Mark Ozias reads a proclamation marking Indigenous People’s Day.

The proclamation has grown over time—from a symbolic replacement for Columbus Day into something heavier, something more accusatory. It labels the legacy of systemic racism as the ongoing source of today’s “poverty and income inequality, exacerbating health, education and social crises” for Indigenous People.

At 2023’s ceremony, Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe Treasurer Theresa Lehman stated:

“Unfortunately, for several years, due to colonization, we were victimized… Our children were taken. Some never returned. We will never, ever allow our children to face these tragedies again.”

No one denies that historical trauma occurred. But Lehman has not personally had her children taken. The people listening to the proclamation have never taken children away. This is an inherited narrative of victimhood and blame. But is it fair to continue shaming people who’ve never done harm—and awarding special status or wealth to people who were never harmed?

A conflict of interest in plain sight

These questions take on new urgency when we follow the money.

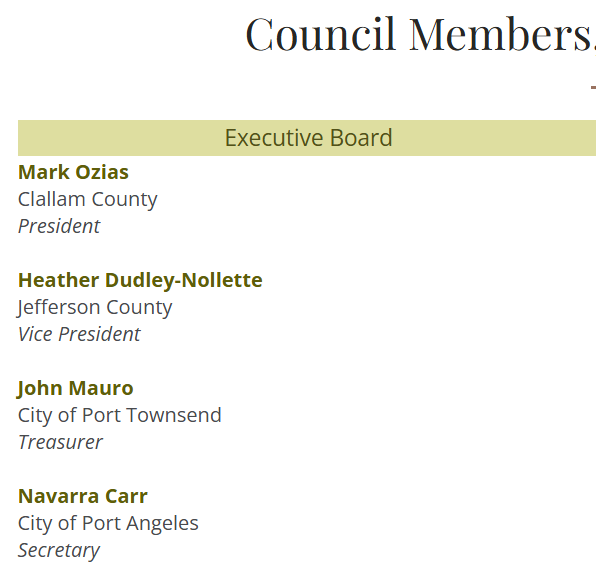

Commissioner Ozias recently opposed a charter amendment that would prevent county commissioners from serving on boards that receive county money, contracts, or in-kind support. Why? Because he serves as president of the North Olympic Development Council (NODC)—a powerful nonprofit that receives and distributes public funding.

The NODC is the fiscal sponsor of the Strait Ecosystem Recovery Network (SERN)—one of ten “Local Integrating Organizations” for the Puget Sound Partnership (PSP). These groups help craft regional “Action Agendas” that shape everything from shoreline regulations to housing, transportation, and development grants.

In short, Commissioner Ozias helps lead an NGO that receives public funds to pursue agendas involving “reparative justice,” tribal sovereignty, and systemic equity. Through this role, he influences where millions of dollars go—even as he denies any conflict of interest.

Forgotten violence: who owes whom?

Much of the current reparations rhetoric focuses on historical injustices committed by settlers—but history in Clallam County is far more complex.

According to HistoryLink, in 1868, the S’Klallam Tribe raided a group of Tsimshian travelers resting on Dungeness Spit. The attack, in retaliation for the theft of a wife from a S’Klallam man named “Lame Jack,” left 17 people dead—men, women, and children—slaughtered with clubs, knives, and guns. After looting the victims, the S’Klallam even turned on Lame Jack, shooting him for trying to make off with too much of the plunder. A wounded, pregnant Tsimshian woman escaped to the lighthouse and was protected by settlers. Her account later gave Graveyard Spit its name. The Tribe that committed the massacre later purchased land east of the site using gold coins—possibly from that same raid—and founded what is now Jamestown.

This was not an isolated event. Tribes in the region—including the S’Klallam, Makah, Hoh, and Quileute—conducted slave raids, engaged in warfare, and in some cases, displayed enemy heads on poles. Chief Seattle himself led the joint Suquamish–S’Klallam raid that destroyed the Chemakum Tribe in 1847, enslaving survivors and erasing a people from history. Even the 1808 wreck of the Russian ship Sv. Nikolai reveals how Russian survivors were enslaved for nearly two years by local tribes.

These are uncomfortable truths—but if we’re talking about historic injustice, the full record deserves daylight. Do we owe reparations for past atrocities, or are some groups owed accountability for theirs?

Reparations by any other name

Here’s the reality: what we are witnessing is a redistribution of wealth from people who never harmed—to people who were never harmed.

SERN, NODC, and PSP explicitly frame their work through the language of restorative justice. Their projects prioritize tribal treaty rights, equity for “historically overburdened communities,” and acknowledge “the harms of colonization.” These concepts, woven into the fabric of environmental policy, housing initiatives, and economic grants, are reparations in everything but name.

Take the $35 million in federal RECOMPETE funding awarded to Clallam and Jefferson Counties. Of that total, nearly a quarter will go directly to tribal entities. The NODC made that decision, with input from groups it fiscally sponsors and ideological frameworks that favor historical redress over present-day need.

The missing tax conversation

As Clallam County braces for a possible historic property tax increase, there’s one conversation that still hasn’t happened—the role of local tribes in the county’s tax base.

Unlike most residents and businesses, tribal enterprises are often exempt from state and local taxes, including property and lodging taxes, thanks to federal law and tribal sovereignty. While many tribal members use local roads, law enforcement, courts, and county services, their government and corporations often contribute little to nothing in taxes to support them.

In January, Commissioner Mark Ozias was asked about this very issue during a public meeting. He declined to comment, stating that a regular commissioner meeting was not the place for such a discussion. But once the cameras were off, he allowed a statement to be recorded:

“We are working on setting up a work session conversation, another public conversation, with the Jamestown Tribe about a variety of tax-related issues — property tax-related issues, lodging tax-related issues, etcetera. So, we’ve been in communication with the Tribe. I expect that to happen sometime in the first quarter, but I don’t have a day yet.”

He said it would be a Monday work session—open to the public. But the first quarter came and went. The meeting never happened.

Now, as county commissioners ask struggling residents to pay more, the silence is deafening. When will the Tribe be asked to contribute their fair share? And why is it so difficult to even ask the question?

The numbers don’t lie

Look at the numbers:

Total Clallam County Population is 77,480 (100%)

Native American Population is 2,815 (3.63%)

Jamestown Tribe Members (local) are 209 (0.27%)

Despite being less than 1% of the population, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe reported $86 million in revenue last year, much of it from taxpayer-funded grants. That’s roughly $411,000 per enrolled local member—compared to the median income in Clallam County of just $68,000 per year.

Meanwhile, many working families in this region are trying to survive—putting $10 of gas in their car at a time, choosing between groceries and bills, and praying the rent doesn’t go up.

Who decides what’s fair?

This isn’t just about organizations. It’s about people—and fairness.

The Chairman and CEO of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, Ron Allen, owns a home in Sequim valued at over $1 million. He is ¼ Jamestown by blood quantum. Does he deserve more consideration than a working-class resident who is 100% “colonizer,” to use the language embedded in our local proclamations and policy documents?

Should equity be decided by race, DNA, or ancestry?

Should wealth redistribution be based on history—or on need?

Because here’s what that framework really says: if your parents were colonizers, you must pay. If your great-great-grandparents were victimized, you are owed. This isn’t justice—it’s hereditary guilt and hereditary entitlement.

The question that won’t go away

The link between elected officials, tax-funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and tribal interests raises serious questions. When Commissioner Ozias oversees a group that allocates public money to organizations built on ideological reparations—that is a conflict of interest. And when those decisions increasingly favor a small, powerful elite while many residents fall further behind—that is a moral concern.

So we ask again:

When will this debt be paid?

When does redress become entitlement?

When do reparations become redistribution?

When is enough... enough?

For the sake of transparency, fairness, and the future of Clallam County, those questions deserve real answers—not just proclamations.

Last Sunday, readers were asked if it is acceptable for a healthcare provider to deny services if a patient refuses to disclose private medical information about a disability. Of 152 votes:

19% said, “Yes, for providers’ safety”

42% said, “No, for patients’ rights”

39% said, “Depends on the content and risk”