“Free” is the most expensive word in Clallam County. Free housing, free food, free drug paraphernalia, free lunches, free grants—programs that sound compassionate on paper but shift costs onto families and businesses while fueling the very crises they claim to solve. From out‑of‑state troublemakers cycling through our jails, to encampments growing along our corridors, to a county government that insists “free” doesn’t cost you—Clallam County is living the reality that San Francisco is now trying to escape. Connect the dots on how a culture of “free” invites dependency, blunts accountability, and leaves taxpayers with the bill.

When “free” becomes a magnet

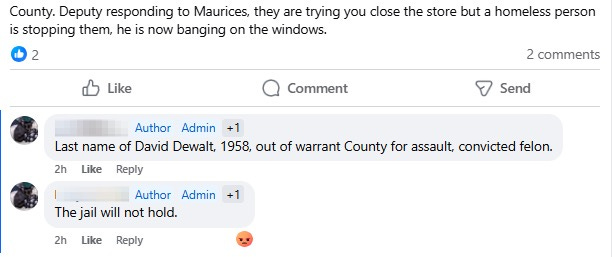

A recent CC Watchdog article described a local business that closed its doors and called the police because a man was yelling and banging on the windows. Scanner traffic reportedly identified him as David DeWalt. Like many transients drawn to the Peninsula by a buffet of “free”—free shelter, free food, free gear, free needles—DeWalt is not from here, but his history keeps landing here.

A 2017 report in the Kitsap Sun documented DeWalt’s arrest in Bremerton for felony malicious harassment and fourth‑degree assault after he allegedly hurled slurs at women outside a Sixth Street bar and head‑butted one of them, sending her to the ER. Witness accounts and police reports described him as “highly intoxicated.”

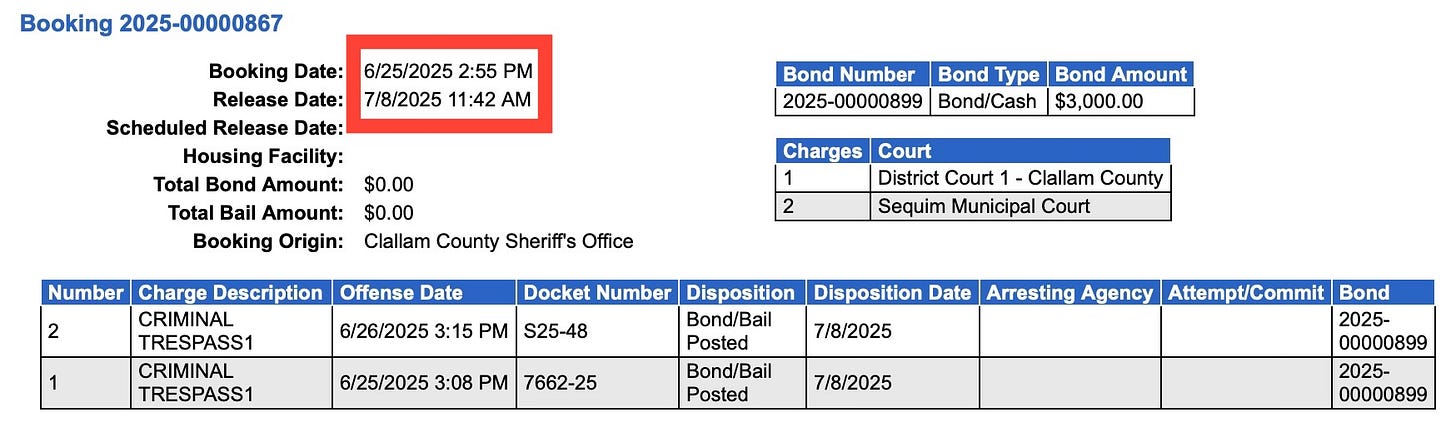

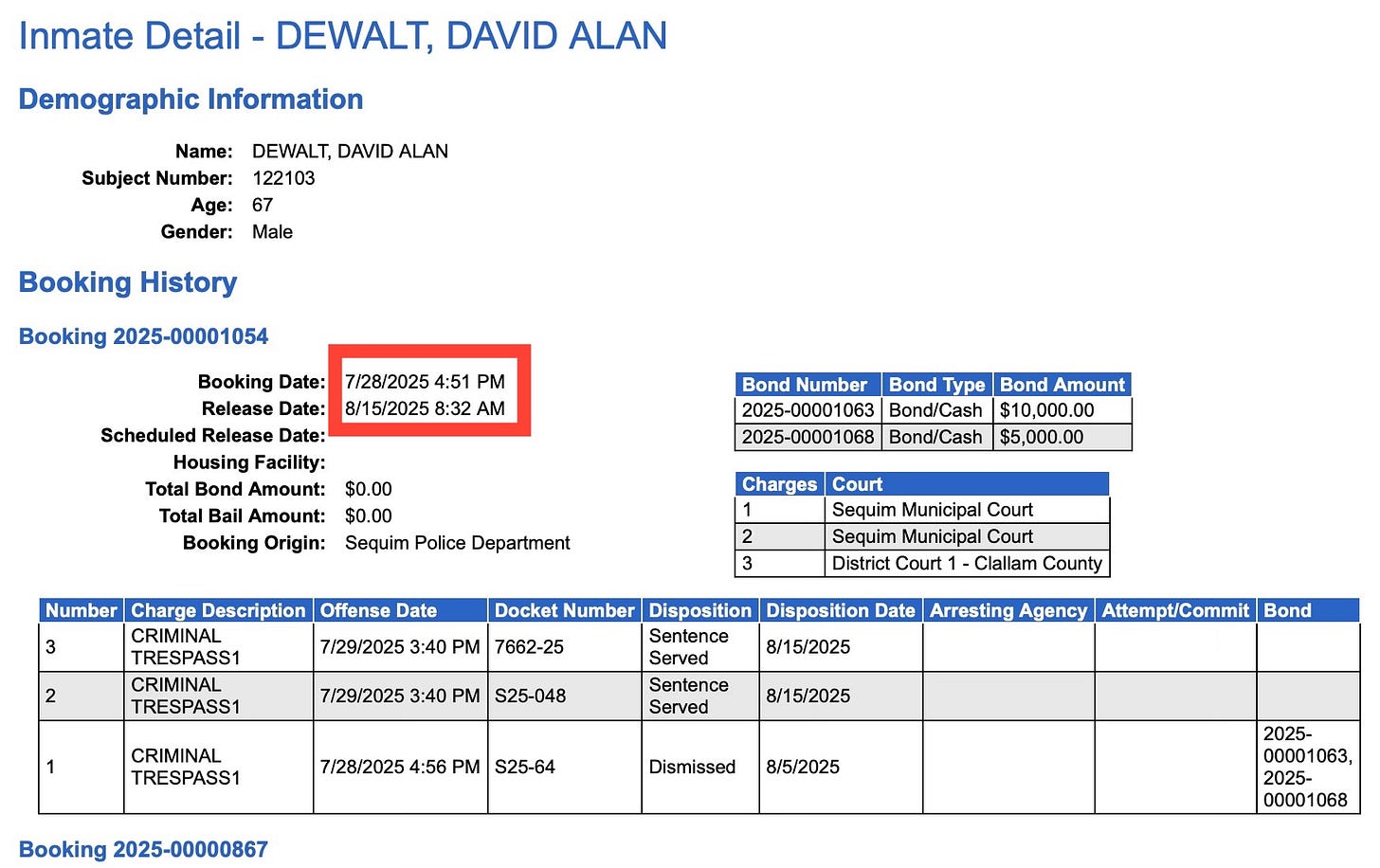

Locally, DeWalt’s name continues to surface in scanner chatter and booking notices, including multiple criminal trespass arrests this summer with quick releases.

A pattern has developed for DeWalt: a revolving door that serves neither public safety nor recovery. When “free” becomes the primary policy tool, consequences get waived along with the costs.

Are we really helping our neighbors in crisis if the system keeps them cycling—rather than changing—behavior? Compassion without accountability is not mercy; it’s neglect.

The Chase: a reader’s close call

(From CC Watchdog comments, lightly edited for clarity.)

“Last Friday evening I was walking to an exercise class in downtown Port Angeles after work. At the transit center, security was talking to a man rolling on the ground under the covered area. As I passed, the guard asked how I was doing. I kept moving—but then heard shouting behind me. At the bottom of the stairs, I turned and saw the man sprinting toward me. The guard managed to get ahead of him to keep him from reaching me. I ran inside a building, yelled for help, and pulled the door closed while the guard worked to get the man to leave. After class, I changed jackets, exited a different way, and detoured several blocks to get back to my car.

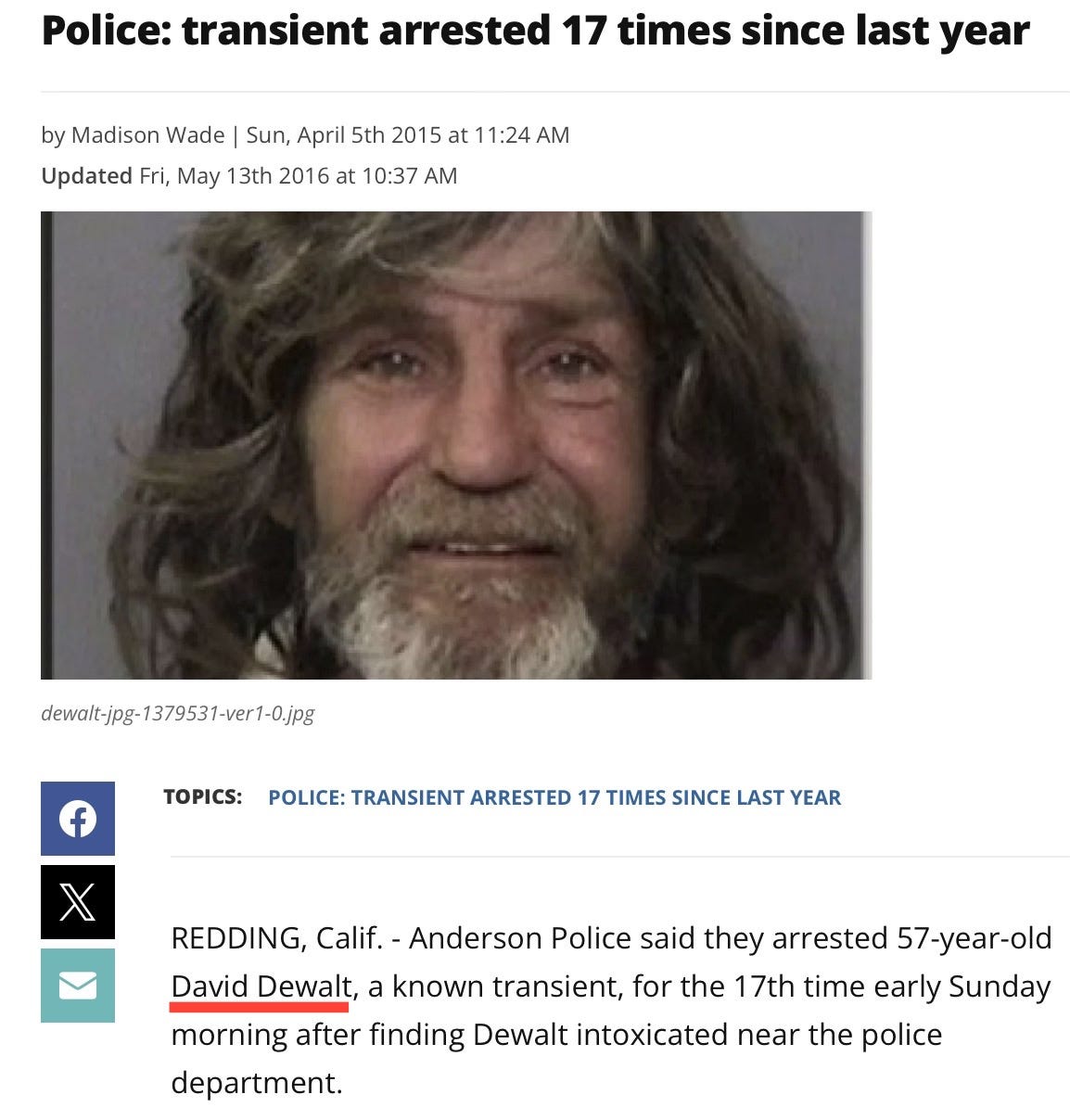

“Later, I looked up criminal history connected to the name that had been circulating and found an article—with a photo—of the same man. His hair is grayer now, but I’m sure it’s him. The article said he had been arrested 17 times in one year. This is the kind of volatility our retail workers and residents are dealing with. Harm‑reduction as practiced here isn’t reducing harm; it’s drawing danger.”

The reveal? The article she found was about David DeWalt. When locals must alter routines, switch jackets, and plan escape routes to avoid a single person, something fundamental has broken—policy, culture, or both.

Out of state, on our streets

This is what we know:

A 2016 news report from Redding, California, detailed repeated arrests of DeWalt—17 bookings in a short span—for public intoxication and probation violations, including an incident where he defecated in a resident’s yard.

Police quoted him as asking to be moved to a town where he wouldn’t be recognized.

The following year, Dewalt was charged in Bremerton for striking a woman and headbutting her in the face.

Now, Dewalt is a “frequent flyer” in the Clallam County Jail.

Addiction travels. So do incentives. When cities and counties are known for easy services and light consequences, word spreads.

Port Angeles and Clallam County don’t exist in a vacuum; we are downstream from state policy and from West Coast norms. If we advertise “free” with minimal expectations, we shouldn’t be surprised when people come for exactly that.

Harm reduction, or harm permission?

Port Angeles is the de facto harm‑reduction capital of Clallam County. The theory—meet people where they are, keep them alive, connect them to help—has an obvious moral appeal. But in practice, the model here (and in several big cities) has drifted from pathway to recovery into subsidy for ongoing use.

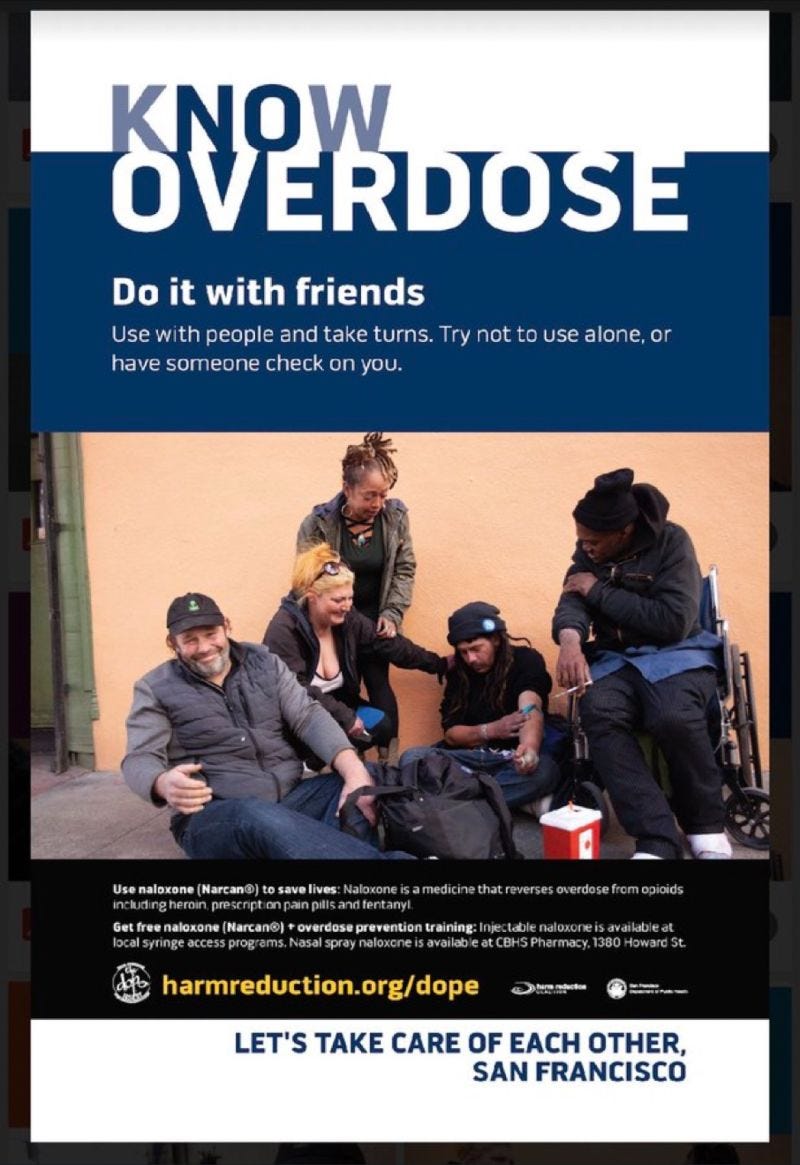

San Francisco—the national case study—is edging away from the orthodoxy. Overdose deaths there hit 810 in 2023 (roughly one per thousand residents). After decades of needle giveaways morphing into pipe and “safer smoking” kits, and a “Know Overdose” campaign that effectively normalized social drug use, city leadership is pulling back. Why? Because what was billed as compassionate turned out to be catastrophic.

Contrast that with Miami’s exchange model, which ties distribution to collection, embeds treatment referrals, and actually channels people into recovery—reporting thousands more needles collected than distributed and meaningful placements into treatment. Harm reduction works only when it is relentlessly recovery‑oriented: on‑site counselors, immediate detox access, and a culture that treats sobriety as the goal, not an optional footnote.

Clallam County can learn from both examples. If we insist on “free,” then make the free thing the on‑ramp to recovery, not the fuel line to overdose.

Read the article that dissects San Francisco’s approach and says that the city is finally turning away from the harm reduction model here: Rethinking “Harm Reduction”

“Free” food—but are the numbers real?

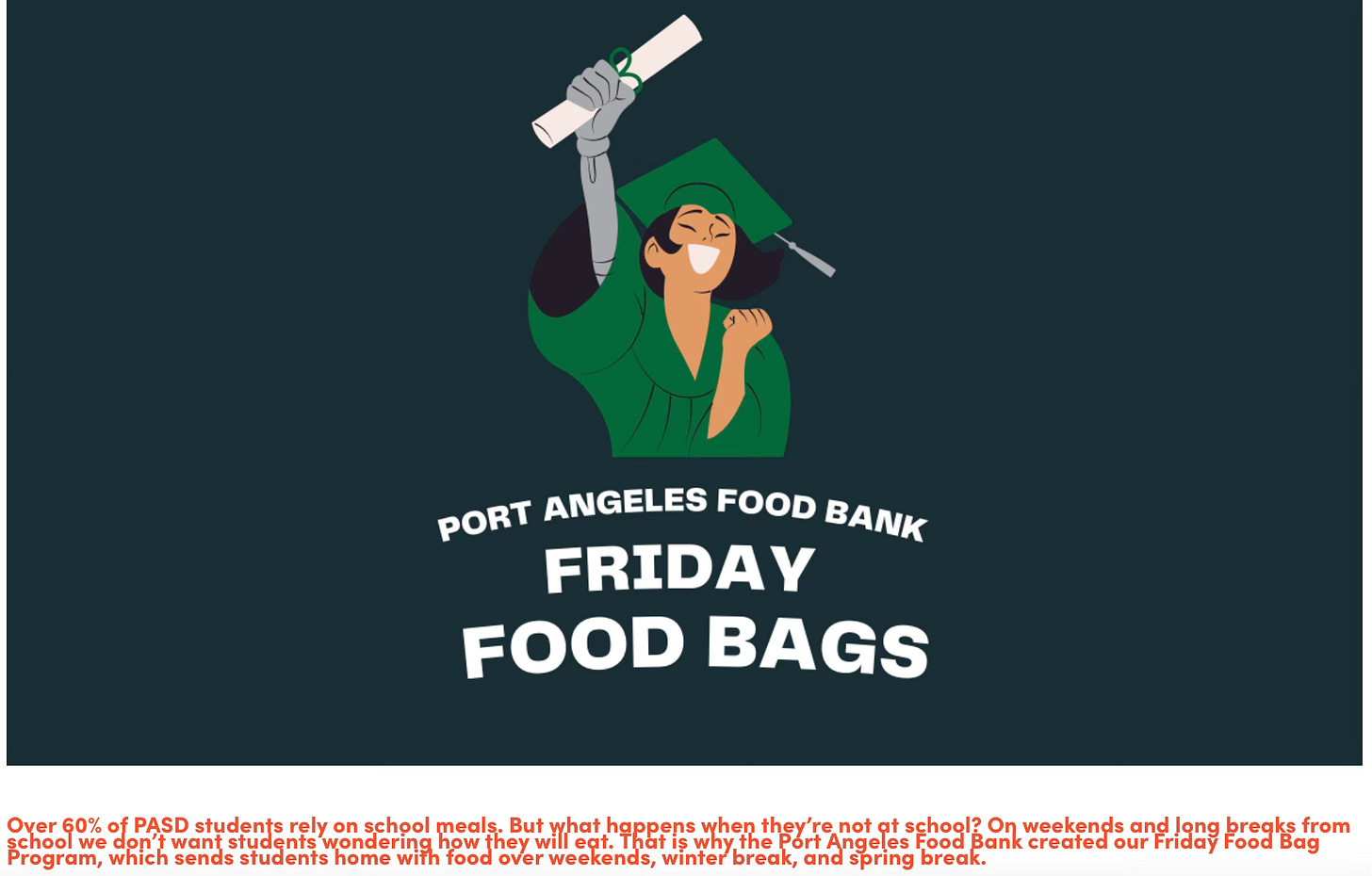

The Port Angeles Food Bank says over 60% of Port Angeles School District students rely on school meals, with the “Friday Food Bag” program sending food home over weekends and breaks.

Feeding hungry kids is right and non‑negotiable. But in an era where “free” grows without scrutiny, hard questions matter:

Does the 60% figure reflect genuine need—or the natural human response to “free” offerings?

What verification exists to distinguish hardship from convenience?

How are outcomes tracked (attendance, performance, household stability) to ensure we’re solving a problem, not inflating a metric?

Compassion requires stewardship. If the number is real, it demands a broader economic conversation. If it’s inflated by policy design, it deserves recalibration.

If a gas station offers free gas, and a thousand people fill up their tanks, are 1,000 people too poor to buy gas?

Free school meals for all—but who pays?

The Port Angeles School District is participating in the federal Community Eligibility Provision (CEP), making breakfast and lunch free for all enrolled students in participating schools for the 2025–26 school year. Families don’t fill out Free/Reduced applications while CEP is in effect, but the district still collects a Family Income Survey to secure related state funding.

Keep the language honest: it’s not “free” if taxpayers fund it. CEP can be a lifeline in truly high‑poverty districts; it can also be a political sleight of hand when universal “free” masks who pays and how much. If we’re going to use it, publish the full cost, the source of funds, the expected benefits—and the off‑ramps if the benefits don’t materialize.

When saying “no” is compassion

In Cowlitz County, Commissioner Rick Dahl set off a debate by urging the board to decline an $11 million state homelessness grant, arguing that big grants can attract more homelessness by expanding services without accountability. Whether you agree or not, it’s a conversation worth having in Clallam County. If spending patterns draw more demand than they resolve, maybe the “compassionate” choice is to refuse the check until the strategy changes.

Saying “no” to failed models isn’t cruelty. It’s leadership.

The bill comes due

Statewide, watchdogs have chronicled an unsustainable surge in Washington spending, as Olympia green‑lights programs faster than taxpayers can afford them. Locally, the same dynamic plays out at a smaller scale—new initiatives, new positions, and new “free” offerings that never seem to sunset. Each press release announces a benefit. Few mention the liability. The arithmetic is simple: when government promises more “free,” either taxes go up, services get cut elsewhere, or both.

Clallam County can’t print money. We can only pass the hat.

Encampments are not “shelters”—they’re shadow cities

Drive the Tumwater Truck Route under the 8th Street bridge and watch the encampment evolve from tarps to stick‑built structures. Law enforcement across Washington describes what follows:

Encampments expand from pockets to permanent ones.

Fentanyl floods in; dealers operate openly from vehicles.

Violence escalates—machete attacks, stabbings, shootings.

The “revolving door” spins: arrests, quick releases, back to business.

The people harmed most? The addicted, the unhoused, and the neighborhoods trapped between fear and fatigue. Real help means setting boundaries: no‑use zones, no‑go zones, and pathways to treatment that are immediate, local, and enforced.

If you want a glimpse of where this ends, watch any number of West Coast encampment exposés: neighbors give up, businesses leave, and the politics harden into a stalemate where everyone loses.

A chance to be heard: Commissioner Forum

For the first time since last October, the Clallam County Board of Commissioners is hosting a real two‑way dialogue after the public meeting today (Tuesday) at 10:00 AM (the Q&A may be closer to 11:00 AM). This session is expected to be 45 minutes.

Click here to learn about attending in person or remotely, and look at the comments section in that link where residents unable to attend have posted their questions. New to public comment? Pick any question and read it during the Q&A. Public comment is one of the most important parts of democracy. Get your feet wet.

The microphone is open. The only question is: will you use it? Oh, and the best part… It’s FREE!