In Richmond, British Columbia — just 60 miles north of Clallam County — homeowners are being warned their property titles may no longer mean what they thought they did. A court ruling recognizing Aboriginal title over developed urban land has shaken investor confidence and sent mayors scrambling. Most people never saw it coming. The question for Clallam County residents is simple: are we paying attention?

What Is “Land Back,” Really?

“Land Back” is described as an Indigenous-led movement seeking the return of lands to tribes based on historic occupation, treaty rights, or Aboriginal title.

In practice, that can mean:

Expanding tribal land bases

Co-management of public lands

Restoration projects that alter private property access

Legal claims that traditional rights predate ownership

The language is everywhere now:

“Ancestral lands.”

“Since Time Immemorial.”

“Stewards of the land.”

“Reserved rights.”

“Government-to-government.”

“Traditional ecological knowledge.”

“Rights of nature.”

It shows up in proclamations, school curriculum, advisory board meetings, museum exhibits, library programming, and planning documents.

Most people don’t notice. Why would they?

What Just Happened in British Columbia

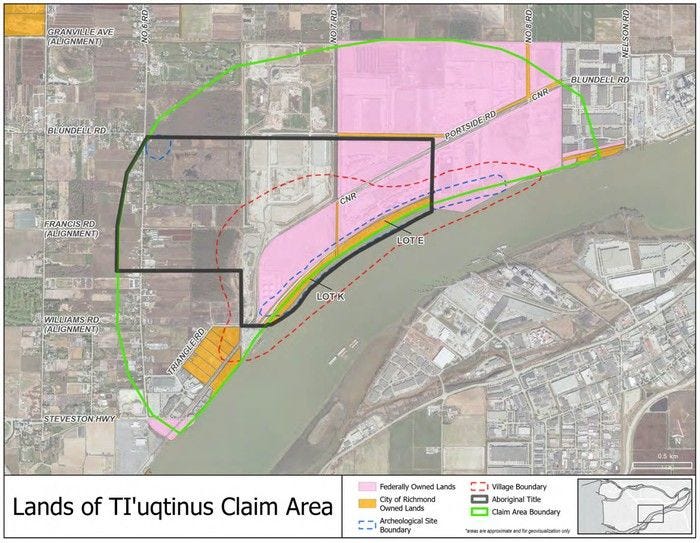

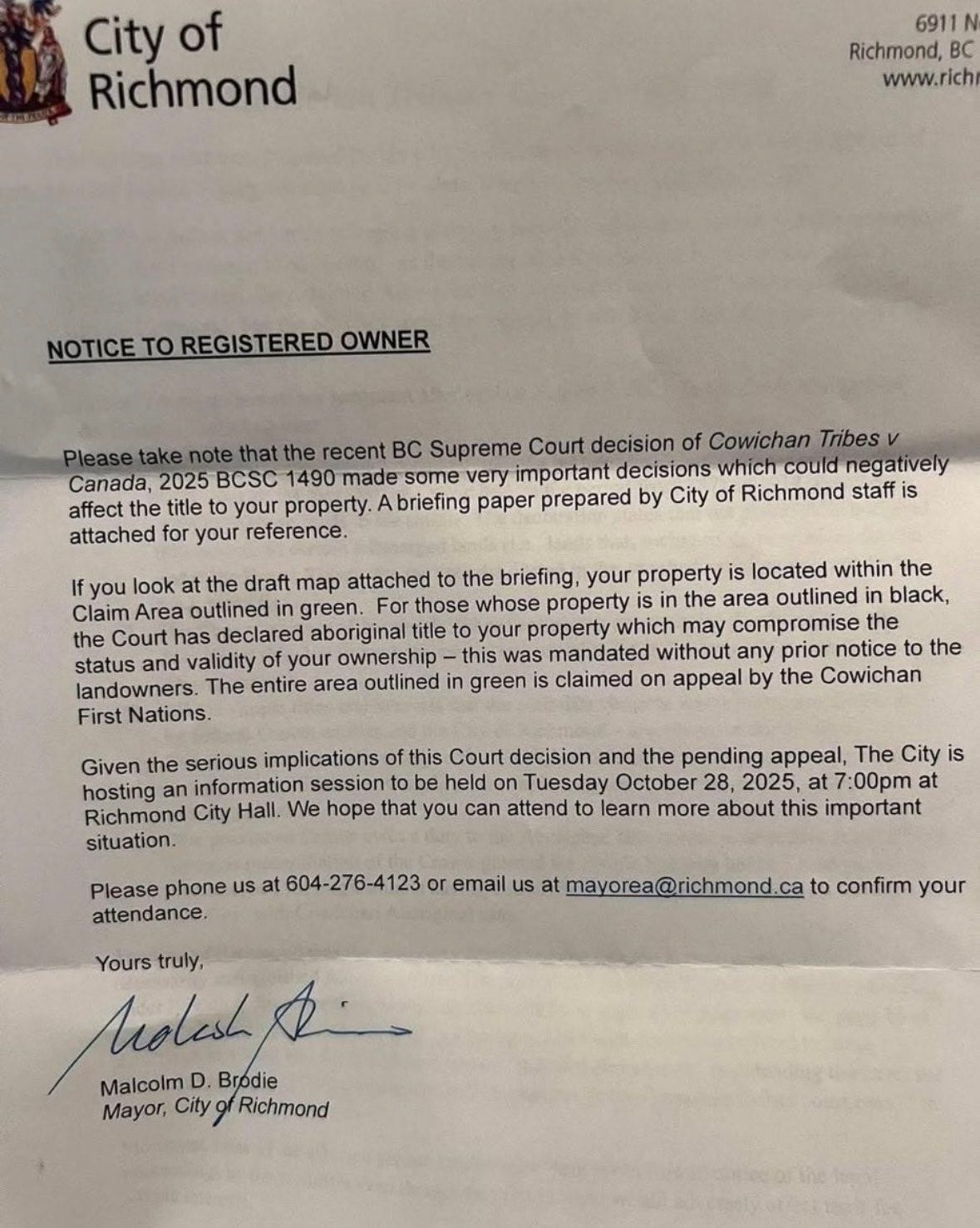

In Richmond, B.C., a B.C. Supreme Court judge recognized Aboriginal title claims by the Cowichan Tribes over portions of Lulu Island — land that includes homes, businesses, and infrastructure near Vancouver International Airport.

The judge wrote that Aboriginal title is a “prior and senior right to land.”

Let that sink in.

Richmond’s mayor, Malcolm Brodie, sent letters to thousands of homeowners warning that their property ownership could be affected. The city scheduled emergency information meetings. Residents were “upset in the extreme,” according to reports.

Here’s the part that should make everyone pause:

Hundreds of people had no idea there was even a trial happening.

It lasted years.

It concluded.

And only afterward did they learn that the ground under their homes might not be theirs.

The case is under appeal. But the precedent is already shaking confidence.

If Aboriginal title can coexist with — or supersede — ownership there, people are asking what stops similar claims elsewhere.

“That’s Canada”

That’s what people say.

But ideas don’t respect borders.

And we are already watching the cultural and policy groundwork being laid here in Clallam County.

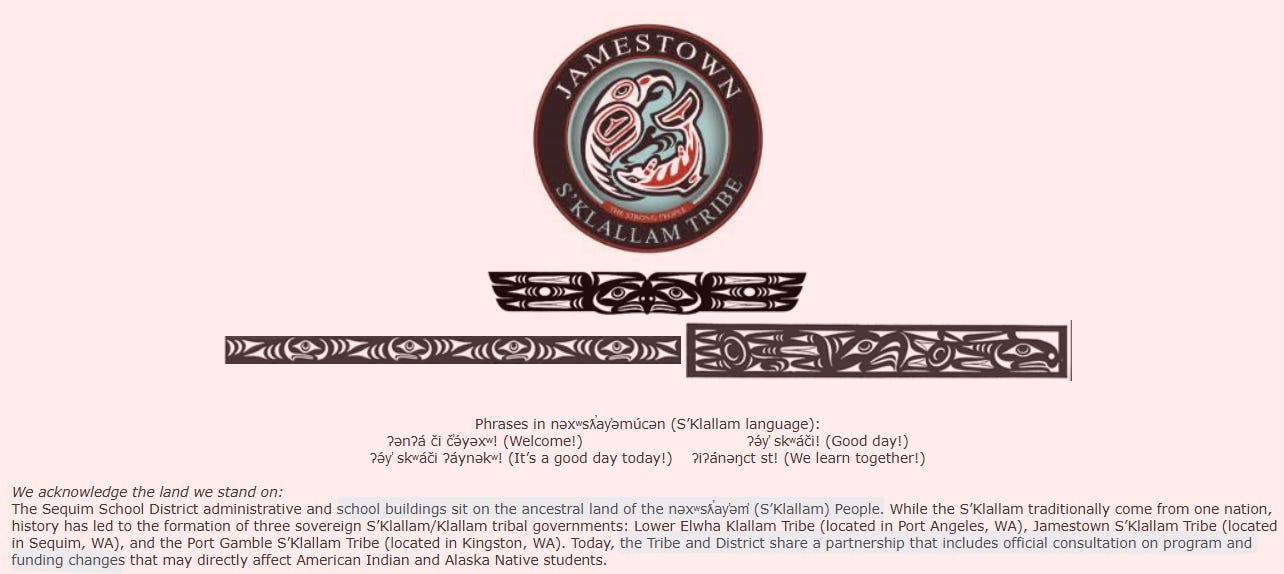

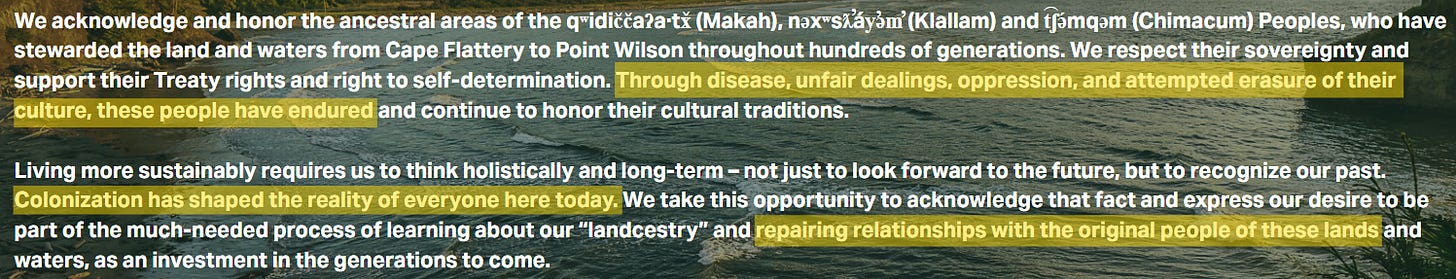

The Sequim School District acknowledges its buildings “sit on the ancestral land of the S’Klallam People.”

The County Fair Advisory Board opens each meeting by recognizing “reserved territory rights” and referring to tribes as caretakers of the land [Click here and advance to 2:55 to hear the Fair Advisory Board’s land acknowledgment read by Cindy Kelly.]

Each year, the county commissioners read a prolamation that shames colonizers for continuing to perpetuate systemic racism against indigenous people.

The Sequim High School’s football field was reanemd to “Stáʔčəŋ Stadium.”

These statements are framed as respectful.

But they also normalize a particular understanding of land ownership — that current legal title exists on top of something morally prior.

That matters.

Because law often follows culture.

Schools and Messaging

Washington’s “Since Time Immemorial” curriculum is increasingly embedded in classrooms and the Jamestown Tribe has introduced it to the Sequim School Board.

Locally, the League of Women Voters has promoted civics materials tied to tribal governance and sovereignty discussions.

The North Olympic Library System recently highlighted Native American Heritage Month with curated materials — including a children’s book titled What Is Land Back?

The book defines Land Back as an Indigenous-led movement rooted in the idea that European colonization forcibly took land.

History should be taught honestly.

But when political movements are packaged for elementary-aged children without full historical complexity, parents deserve transparency.

Because these conversations are not just about the past. They are about policy today.

Policy Is Where This Becomes Real

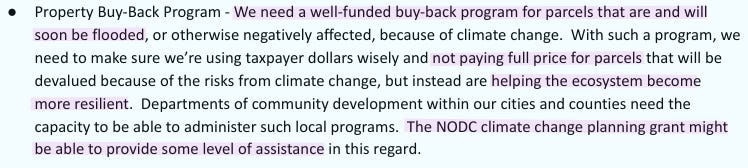

In 2021, the Strait Ecosystem Recovery Network (SERN), whose fiscal agent is the Jamestown Corporation, held a workshop to discuss acquiring waterfront property through influencing comprehensive plans and law makers rather than paying full market price.

After the Meadowbrook Creek re-engineering project in Dungeness worsened flooding in the 3 Crabs area, Clallam County’s Marine Resources Committee — chaired by Jamestown employee and tribal member LaTrisha Suggs — called for removing 3 Crabs Road and relocating residents.

Relocation.

That’s not symbolic language.

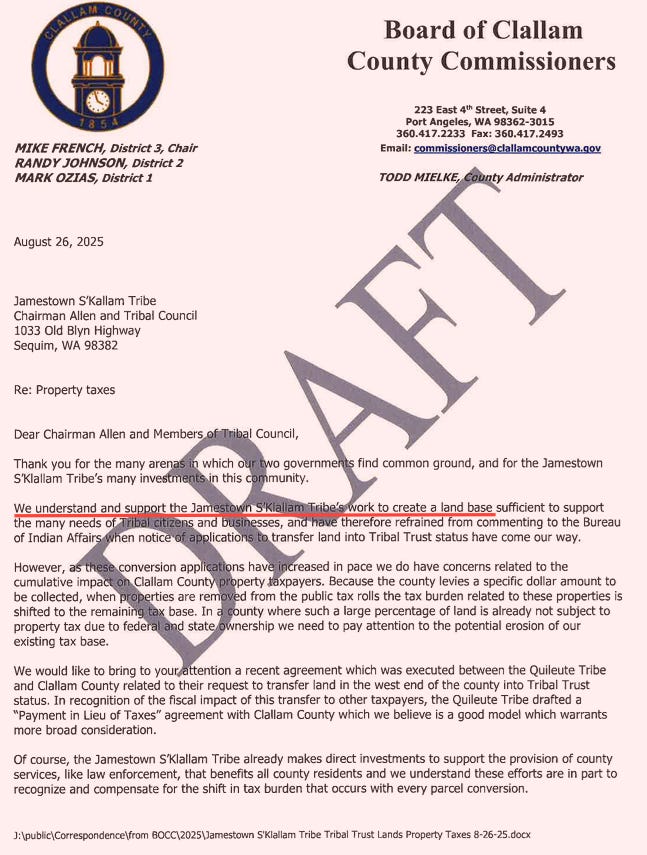

At the same time, commissioners have publicly stated they intend to help “build the land base to which the Tribe is entitled.”

Those words matter.

They signal that expanding tribal land ownership inside county boundaries is an active policy objective — not a hypothetical.

The Part That Gets Simplified

Modern Land Back narratives often frame history as colonizers versus Indigenous peoples.

Reality is more complicated.

Long before Europeans arrived, territory changed hands. There were conflicts. There were alliances. The Chemakum people were nearly exterminated in 1847 by coordinated attacks from the S’Klallam and Suquamish tribes. The Jamestown Tribe massacred 17 members of the Tsimshian Tribe in 1868.

That doesn’t erase injustices committed later.

But it does mean the story of “who took land from whom” is not as simple as the slogans suggest.

When policy is built on simplified narratives, nuance disappears. And nuance is where property law lives.

The Transparency Question

In British Columbia, the provincial government has proposed allowing closed-door municipal meetings when discussing “culturally sensitive” information shared by First Nations.

Critics argue this reduces public oversight at the exact moment major land and title questions are unfolding.

In Clallam County, more and more decisions are framed as “government-to-government” discussions — arrangements that often take place outside ordinary public channels. When those meetings occur on sovereign tribal land, Washington’s open-meeting and public disclosure laws do not necessarily apply, leaving residents without the transparency they would expect in other county matters.

If land base expansion is a goal, voters deserve clarity on:

What land?

Under what authority?

With what limits?

And with what protections for private property owners?

Most People Aren’t Paying Attention

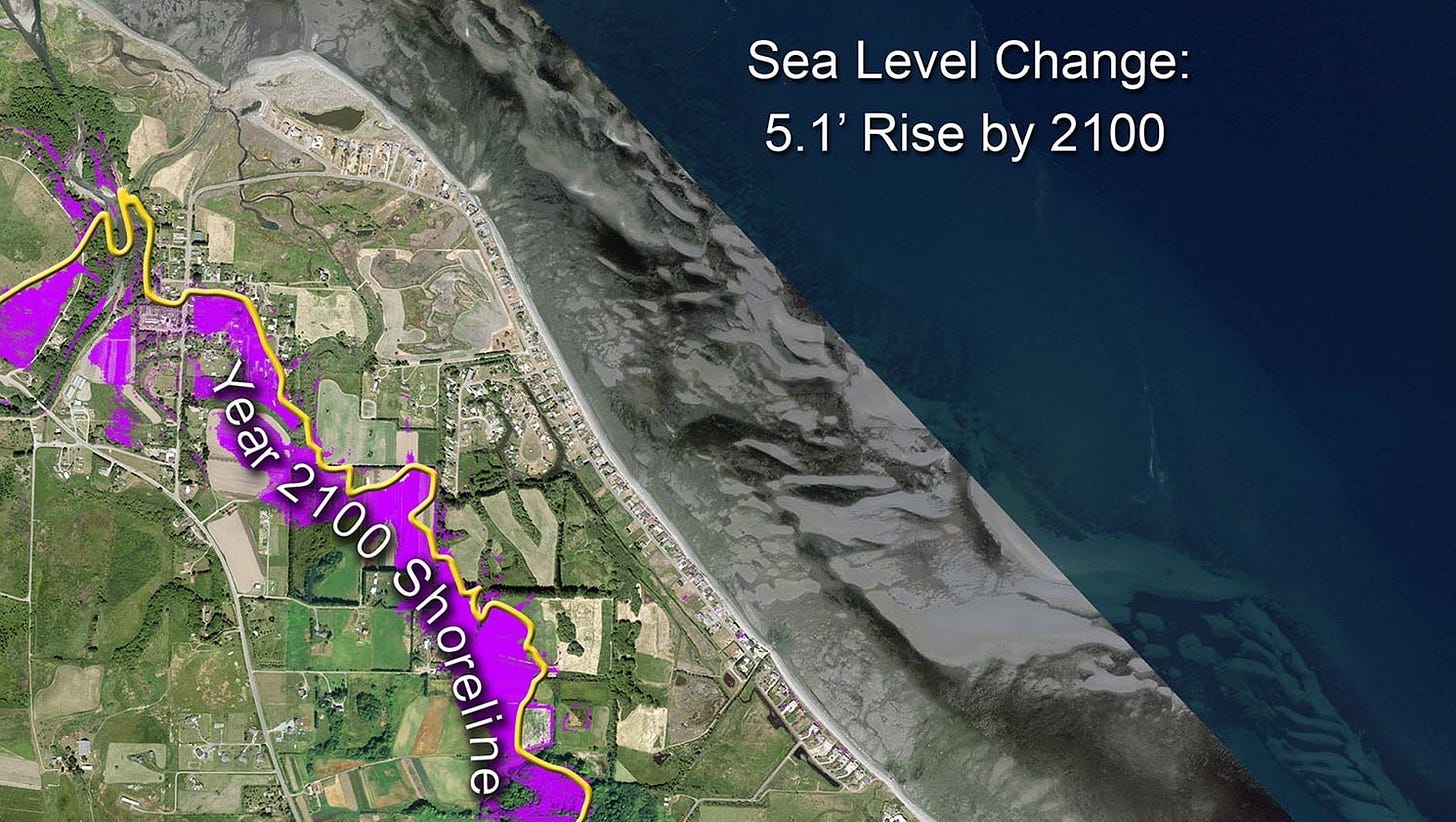

That’s the real parallel with Richmond.

Homeowners there assumed:

They had clear title.

They had legal protection.

The system would alert them if something fundamental changed.

Instead, the case unfolded quietly until the ruling dropped.

Only then did they realize they were in the “danger zone.”

Land Back Is Here

Not in the form of eviction notices.

But in:

Acknowledgments.

Curriculum.

Advisory committees.

Habitat restoration plans.

Planning language.

Public statements about building tribal land bases.

Cultural normalization first.

Policy second.

Legal structure third.

That’s the pattern we just watched unfold north of us.

The Question for Clallam County

No one is saying private homes in Sequim are about to be handed over.

But if your elected commissioners openly say they will help expand a sovereign nation’s land base within the county…

If advisory boards chaired by tribal employees recommend relocation of residents…

If curriculum teaches children that current land ownership sits on morally illegitimate ground…

Is it unreasonable to ask:

Where are the guardrails?

Because Richmond homeowners thought they had them.

Until they didn’t.