From hospital losses to tribal land deals, costly bike projects to revolving-door justice, Clallam County residents are left wondering: whose interests are really being served?

OMC’s missing millions

At Olympic Medical Center’s latest board meeting, interim CEO Mark Gregson shared alarming news: the hospital’s finances have collapsed. What was a $6 million surplus in 2021 is now projected to be a $16 million deficit in 2025. On top of that, vendor debt has exploded from $8 million to $29 million.

“In 2021 we made a profit of six million dollars. We lost 16 million in 2022. We lost 28 million in 2023. We lost 12 million in 2024. And I project that, if we continue as we’re operating, we’ll lose about 16 million dollars this year.” — Dennis Stillman, Interim CFO

Add it up, and the hospital has bled $72 million in just four years. That’s not a minor downturn — that’s a financial crisis. For a community hospital, this kind of loss threatens not just balance sheets but the very services residents depend on.

The question the public should be asking is: “Where did that $72 million go?”

Water for golf, but not for you

The Snoqualmie Tribe recently condemned a golf course for using water during a drought, calling it an “environmental emergency.” Yet right here in Clallam County, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe runs its own golf course, a water-hungry business that continues operating while the Tribe pressures farms and homeowners to cut irrigation.

The contradiction is hard to miss. If water use during drought is really an emergency, shouldn’t the same standard apply to tribal businesses as well as private ones? Otherwise, it starts to look less like conservation and more like selective enforcement.

This double standard is what frustrates residents. They’re told to sacrifice, while others are free to operate as usual. A fair drought policy would treat everyone equally — not set up one set of rules for tribes and another for everyone else.

Timber battles return

On Monday, county commissioners will hear about the “Doc Holiday Timber Replacement Sale.” It’s presented as a way to protect certain forest lands by swapping out harvest areas for others. But the presenters tell another story: Bill Bryant, a former Port of Seattle commissioner, and Brel Froebe of the “Center for Responsible Forestry,” both oppose traditional timber sales.

For decades, timber has provided funding for schools, county services, and local jobs. When outside groups come in with strategies to curb harvests, residents have to ask: is this really about forest health, or about dismantling Clallam County’s timber economy piece by piece?

At stake is more than a few acres of trees. It’s about whether rural counties like ours still get to benefit from the resources in our backyard — or whether those decisions are being outsourced to activists and officials who don’t live here.

Watch the presentation Monday after 9:00 AM here (no public comment allowed).

Who the County invited to speak

One of Monday’s presenters invited by the County Commissioners is Brel Froebe, executive director of the Center for Responsible Forestry. Froebe’s organization positions itself as an environmental nonprofit focused on forest protection, but Froebe also has a significant activist background tied to social justice movements in Whatcom County.

Brel Froebe has been a member of the Defund the Bellingham Police (Defund BPD) Coalition, which has called for dramatic cuts to police budgets in favor of social services, housing programs, and alternative crisis response systems. Froebe has advocated publicly to end sweeps of homeless encampments and shift resources away from traditional policing toward non-punitive community responses.

Commissioners and residents should be aware that Froebe’s participation in this forestry presentation comes with a broader activist history. While environmental expertise may be relevant, Froebe’s public record shows connections to movements that push for fundamental changes to local governance and law enforcement priorities. Knowing this context allows the public to fully understand who is influencing policy discussions in Clallam County.

Tree park cleanup — but for how long?

Jessie Webster Park, behind Swain’s, was cleared again this week. Tents, garbage, and bike chop shops were hauled away, giving neighbors a temporary break from the chaos.

But residents have seen this play out before. Within weeks, the camps usually return, complete with trash and stolen bikes. Despite millions spent on homelessness programs, nothing changes on the ground for the people who live nearby.

Until the city enforces long-term solutions, it’s just paying for cleanups that don’t last. Taxpayers are left footing the bill for a cycle of temporary relief that never addresses the root problem.

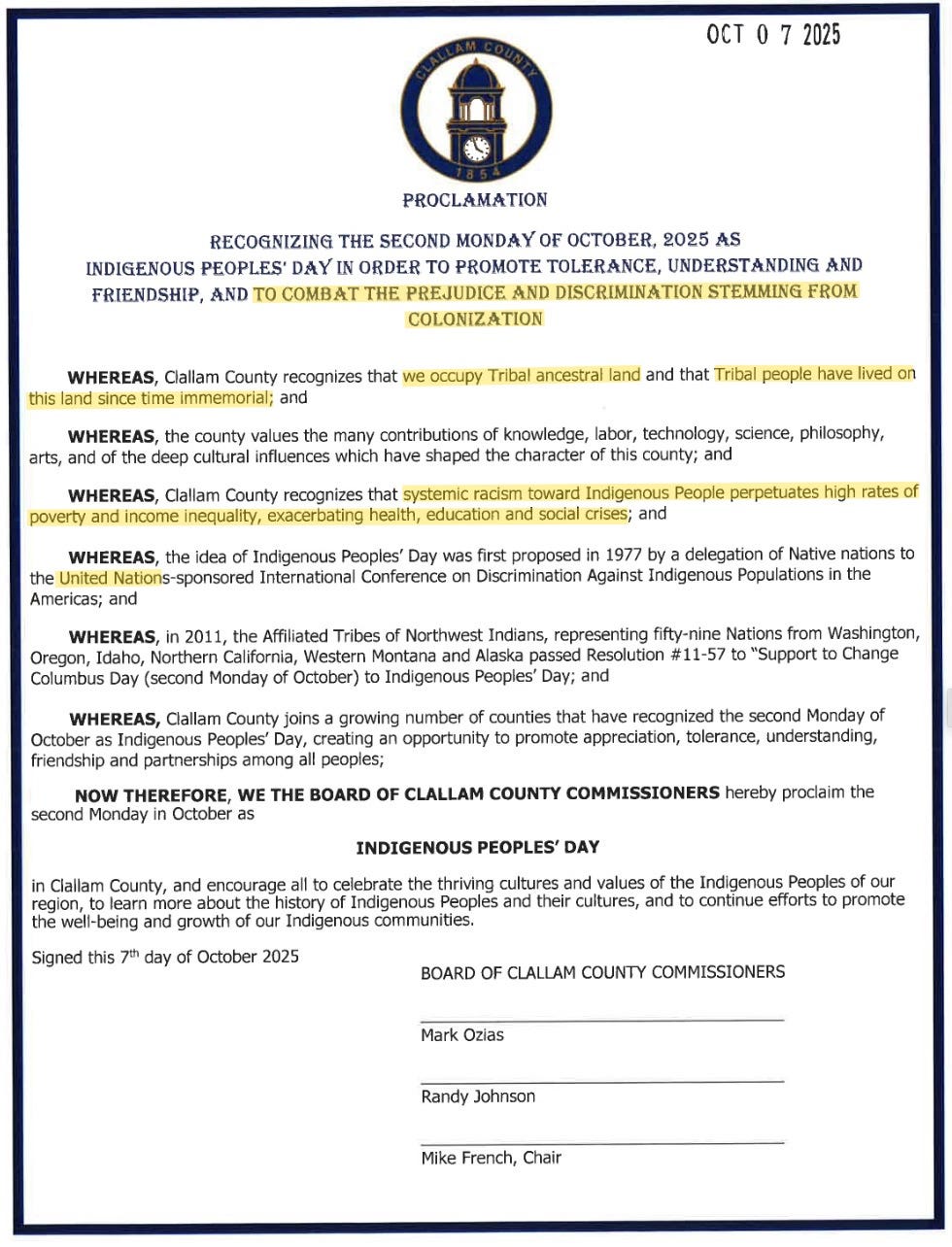

Proclamation politics

On Tuesday, commissioners will issue a proclamation for Indigenous Peoples’ Day. The draft language describes Clallam County as “occupied land” and cites “systemic racism” as the reason for poverty and inequality.

Proclamations like this are meant to signal respect, but too often they create division instead. By framing history through guilt politics, they risk making some citizens perpetual victims and others perpetual oppressors. That doesn’t build unity — it drives wedges.

Citizens who want to weigh in can comment first thing Tuesday morning at 10:00 AM. Commissioners should hear whether residents believe these statements reflect the county’s values — or if they’ve gone too far.

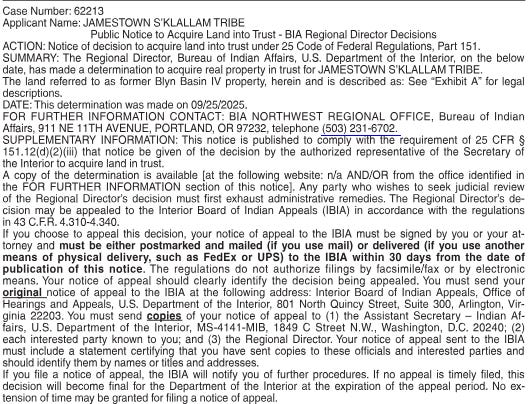

Another one bites the trust

The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe has applied to move more land into federal trust, taking it off the county tax rolls. That means fewer dollars for schools, fire departments, and road maintenance — costs that get shifted back onto non-tribal residents.

Trust land comes with perks. Once approved, it’s exempt from property taxes and local regulation, giving tribal enterprises a permanent competitive advantage. For a Tribe with just 209 loal members and $86 million in annual revenue, the loss to county coffers is significant.

The public should be asking why wealthy enterprises can expand tax-free while ordinary homeowners and businesses face rising taxes to make up the difference. When land leaves the rolls, everyone else pays more.

$200,000 bike lane designs

Port Angeles is pitching a “bike boulevard” project and wants public input. But here’s the catch: the city has already approved nearly $200,000 for consultants to draw up plans, long before a shovel hits the ground.

That figure doesn’t even touch construction costs, which are at least a year away. Residents are left wondering if the city is more interested in funneling money to consultants than actually improving transportation.

As one local put it: “I’d ride more if I thought my bike would still be there when I got back.” Until basic public safety is addressed, pouring money into bike lanes feels like a misplaced priority.

Take the City’s survey here.

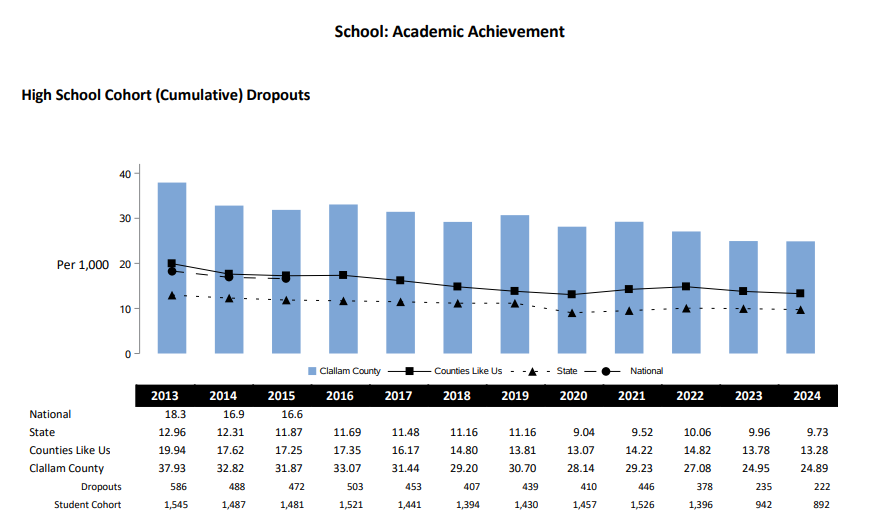

Schools lose focus

The Port Angeles School Board has agreed to share a Klallam language teacher with the Lower Elwha Tribe. In Sequim, schools are being told to teach about colonization in line with tribal priorities.

Meanwhile, the dropout rate for local students is 2.5 times higher than the state average. Parents have to ask: why are schools investing so heavily in political messaging when academic basics like reading and math are being neglected?

Education should prepare students for the real world. If cultural projects take priority over graduation rates, kids are the ones who lose out — and the community pays the price.

Jail as a path to sobriety?

The Clallam County Jail’s Suboxone program has made a big impact: no overdoses among inmates since 2022. Staff say the treatment works so well that addicts are intentionally getting themselves arrested so they can come get clean.

That creates a troubling cycle. More thefts, more burglaries, and more victims mean the public is subsidizing recovery through crime. It’s an unintended consequence that turns a success inside the jail into a burden outside of it.

The program may help inmates, but the county needs to ask whether it’s helping the broader community. If the easiest pathway to sobriety is getting locked up, something is wrong with the system.

Scanner reality check

This week’s scanner calls were a grim highlight reel: unconscious people slumped in cars, out-of-town criminals arrested, someone passed out at a playground, and a man urinating on pumpkins at the grocery store.

Officials call this “harm reduction.” But residents see it differently — a steady decline in safety, quality of life, and public trust.

If millions in taxpayer spending is supposed to be reducing harm, where’s the evidence? What people see daily doesn’t match what officials keep promising.