Local leaders speak passionately about democracy, compassion, and progress during interviews — but too often those words fall flat. From luxury-priced “affordable” housing to the disappearing records of a sovereign corporation. Examples of selective transparency and unanswered calls for public dialogue mount in this Watchdog roundup, which examines how Clallam County’s governing class says the right things while repeatedly failing to serve the public interest.

National Rhetoric, Local Silence

Two county commissioners recently sat down with Clallam Democrats Rising to reflect on the 2025 elections. Commissioner Mark Ozias used the opportunity to focus almost exclusively on national politics, praising candidates who are “not afraid to stand up to bullies” and calling for resistance to “entrenched power structures.”

Commissioner Ozias spoke at length about the president, democracy, liberty, and saving the nation. What was notably absent was any reference to Clallam County itself — no mention of economic development, public safety, taxation, infrastructure, or the very real challenges facing residents here at home.

“We need to understand that the majority of Americans despise Donald Trump and we need to support each other because there are a whole lot of people out there who wish to save democracy in America.” — Commissioner Mark Ozias in Clallam Democrats Rising

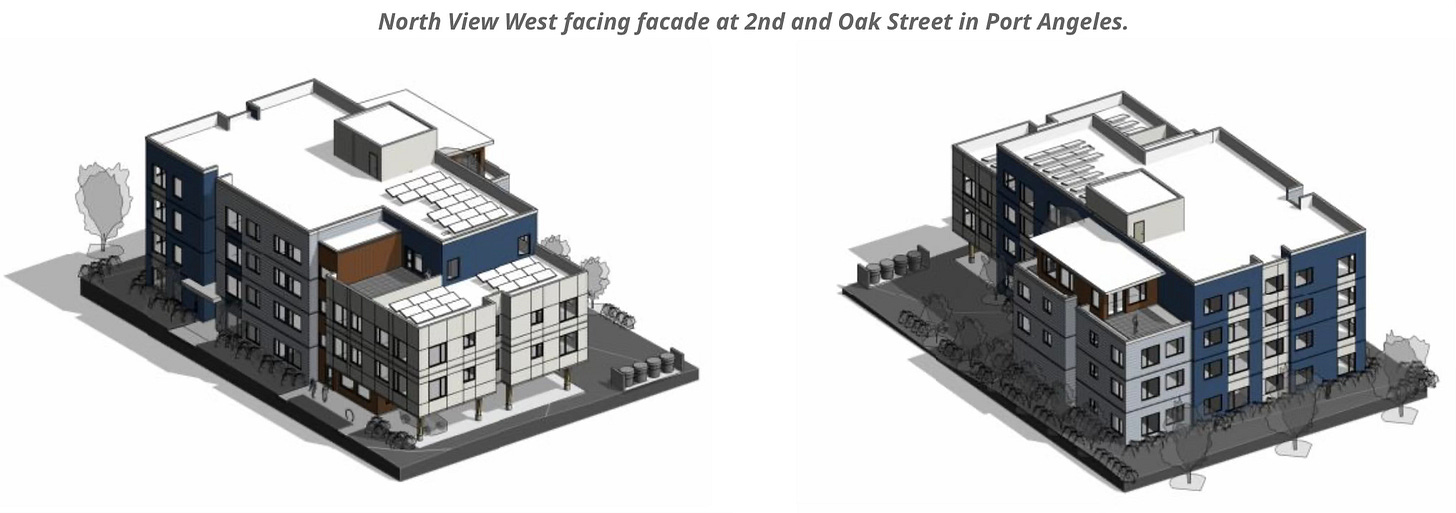

Commissioner Mike French, to his credit, redirected the conversation locally, highlighting what he described as progress on affordable housing — specifically a 36-unit apartment building expected to open in Port Angeles in 2026.

What went unsaid is that the project is Peninsula Behavioral Health’s North View complex — a four-story luxury development featuring rooftop terraces, dishwashers, a dog-washing station, and expansive harbor and mountain views, at an estimated cost of $350,000 per unit. The project is designed to prioritize individuals with frequent incarceration histories, and participation does not require sobriety.

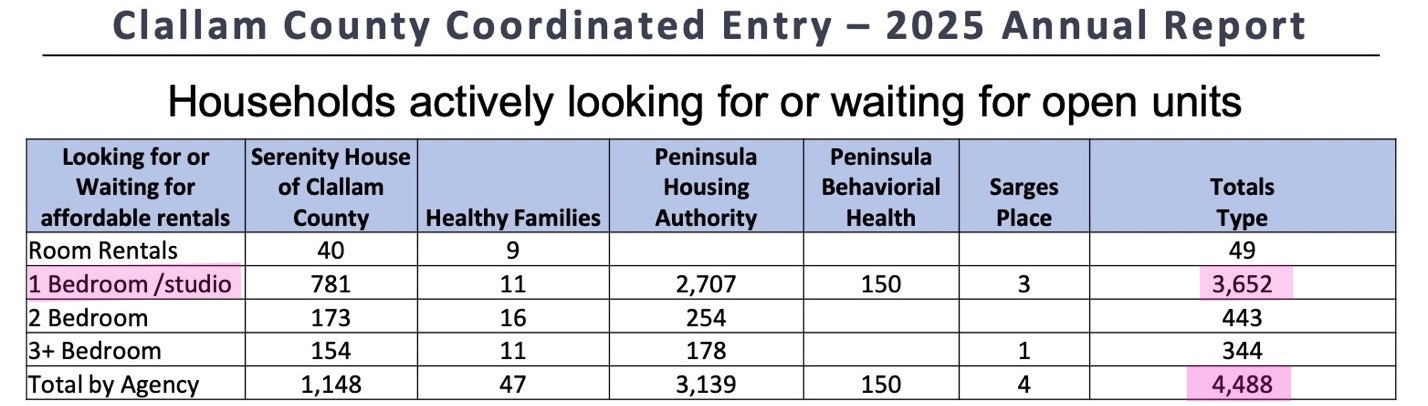

With roughly 4,488 individuals currently looking for or waiting on housing in Clallam County, this approach puts the community well over a billion dollars away from meeting stated housing goals.

Calling $350,000 per unit a success may play well politically, but it raises a hard question for taxpayers: who exactly is this system designed to serve, and who exactly will be paying for it?

Editor’s Note: CC Watchdog requested clarification from Commissioner French regarding statements attributed to him in Clallam Democrats Rising on November 27. He did not respond.

Two Meanings of “Jamestown”

The term Jamestown Tribe has become increasingly confusing — and that confusion matters.

On one hand, it refers to Jamestown tribal members: our neighbors, colleagues, friends, and contributors to this community. Only about 212 members live locally, many deeply integrated pillars in our county. They are not the issue.

On the other hand, Jamestown also operates as a powerful corporate entity — the county’s second-largest employer, generating over $100 million annually, operating a casino, golf course, clinics, a surveying firm, and real estate holdings, while openly touting the competitive advantage of tax exemption.

For clarity, CC Watchdog will use “Jamestown Tribe” when referring to people, and “Jamestown Corporation” when referring to business enterprises.

That distinction matters because the Jamestown Corporation has increasingly described itself as a public entity — while simultaneously removing public access to information. Its interactive parcel ownership map now requires a login. Tribal newsletters have been “under construction” for months. Annual reports have vanished.

When a corporation claims public-entity status but restricts transparency, it is reasonable to ask what scrutiny it is avoiding.

When NGOs Become Untouchable

Marolee Smith’s recent piece, “NGOs Are a Cancer (But They Sure Have Adorable Names)”, is blunt — and intentionally so. She argues that nonprofit organizations have evolved from community helpers into unaccountable power centers that absorb public money while shielding themselves from oversight.

Smith draws on national reporting, congressional testimony, and investigative journalism to show how NGOs can function as a de facto fifth branch of government — advancing policies voters never approved while enjoying near-automatic moral cover.

Her warning is not abstract. Clallam County has seen NGOs refuse to open their books, demand new taxes, pay inflated salaries, and collapse without accountability — all while insisting the public “trust the process.”

Smith closes with a call to action: stop being passive, stop assuming goodwill equals good governance, and start showing up.

Community discussion:

📍 Thursday, January 8, 2026 — 5:00 PM

📍 BarHop Brewing, Port Angeles

A Local Voice in a Statewide Fight

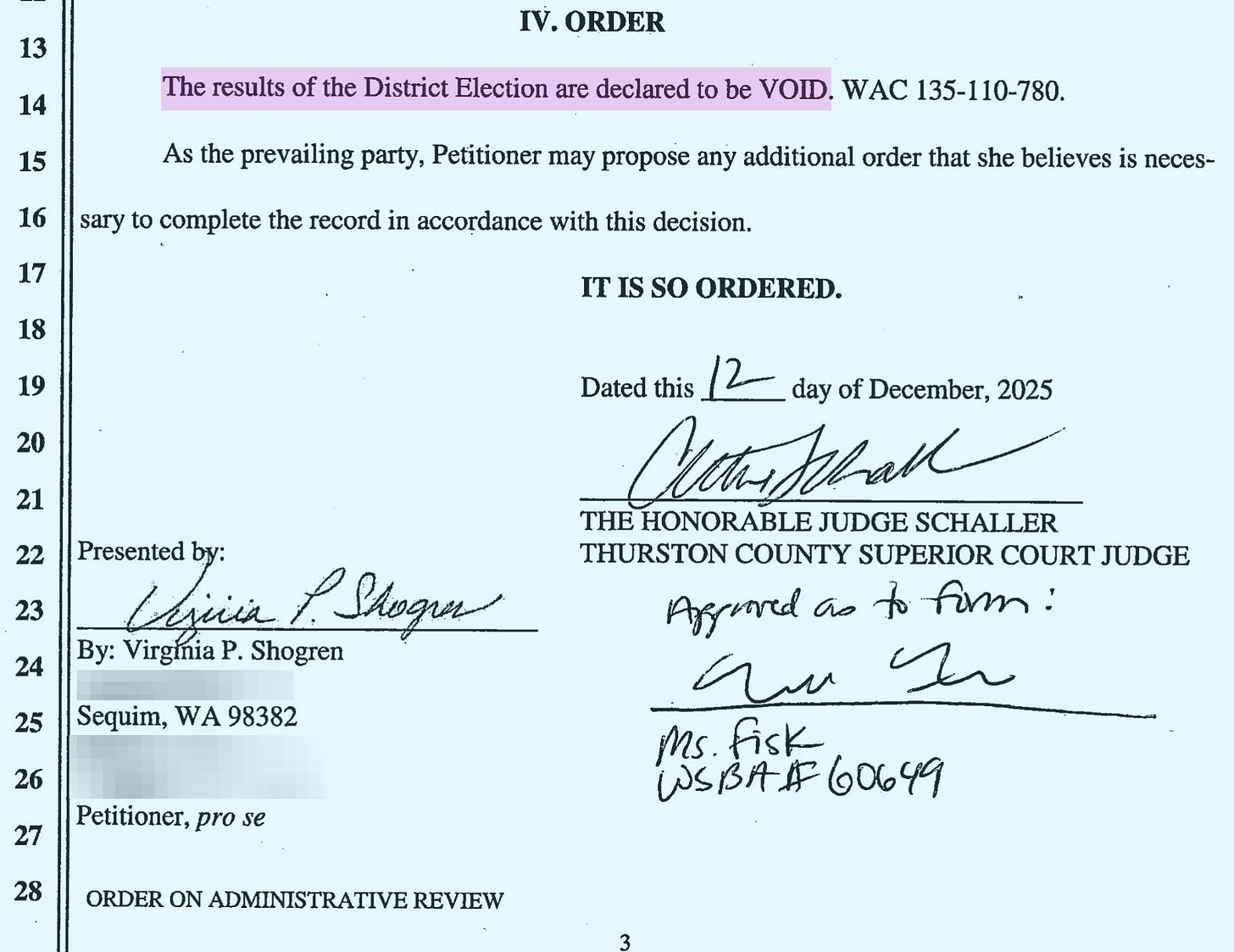

A recent Center Square report highlights the case of Virginia Shogren, a Clallam County resident appealing a two-year suspension of her law license after the Washington State Attorney General’s Office filed a bar complaint against her. The discipline stems from her representation of the Washington Election Integrity Coalition United following the 2020 election, when she challenged Washington’s practice of automatically registering non-citizens to vote through the Department of Licensing as unconstitutional.

Shogren argues the sanction is less about misconduct and more about the subject matter — election integrity — noting that similar voter registration data is now being sought by the federal government in a separate lawsuit against the state. Shogren recently challenged a Clallam Conservation District supervisor election that a Thurston County Superior Court ruled was procedurally flawed. The election has since been declared void, underscoring that challenges to election processes are not theoretical, but local — and that raising them can cost significant time, money, and, in some cases, a person’s career.

How Local Is “Local” News?

Curious how much of the Peninsula Daily News is actually focused on Clallam County, one Watchdogger reviewed a full day of news headlines — excluding sports, lifestyle, and entertainment features.

Out of 25 news headlines, only 7 were truly local. Those included coverage of a tribal–commerce agreement, a Port Angeles orchestra performance, Jefferson Healthcare’s clinic acquisition, a Boy Scouts recycling effort, Peninsula College auditions, and the announcement of new medical providers in Port Townsend.

The remaining 18 stories were not local. They focused on California flooding, national politics, foreign conflicts, global markets, celebrity news, federal appointments, international crime, and national economic trends. None addressed Clallam County governance, taxation, public safety, housing, or infrastructure.

There is nothing wrong with reporting broader news. But when nearly three-quarters of a “local” paper’s news coverage comes from elsewhere, it helps explain why residents increasingly rely on independent outlets and citizen journalists to monitor local government and ask the questions that no longer fit in shrinking newsrooms.

Who Controls the Science?

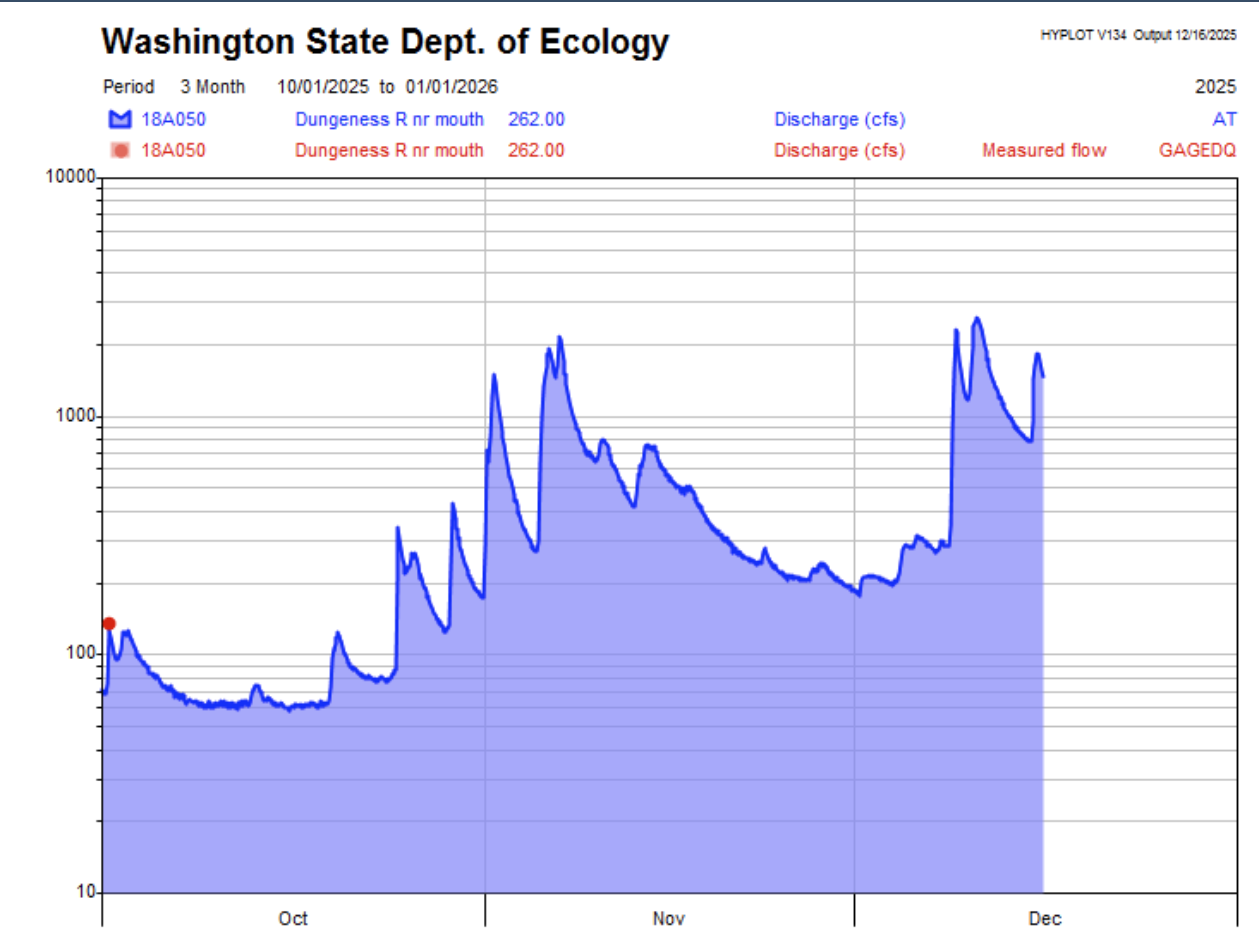

The Dungeness River Nature Center recently posted that “all-time high flows” had tested the river — crediting engineered logjams (ELJs) installed by the Jamestown Corporation for protecting fish habitat.

There’s a problem: the data doesn’t support the claim.

USGS records show historic flows near 7,600 cfs. Recent Department of Ecology data shows flows closer to 2,430 cfs — not remotely record-setting.

Why does this matter? Because millions in grant funding are justified on claims of scientific expertise and restoration success. When the same entity receiving those grants also controls the messaging and interpretation of the science, skepticism is not hostility — it’s due diligence.

This is especially notable given that funding intended to complete Towne Road in 2023 was diverted to the Jamestown Corporation to build Engineered Log Jams.

Editor’s Note: The DRNC has since removed the words “all time” from its original Facebook post.

Who Will Show Up — And Who Won’t

Residents recently asked community leaders to participate in a public town hall addressing:

Out-of-county offenders

Local harm-reduction outcomes

Law-enforcement tools and limitations

Recent violent and public-safety incidents

The response was telling.

Prosecuting Attorney Mark Nichols, Sheriff Brian King, Police Chief Brian Smith, and even State Representative Adam Bernbaum have all expressed enthusiasm about the opportunity to participate.

The only officials who did not respond?

Commissioners Mike French, Mark Ozias, and Randy Johnson.

When trust is low, silence speaks volumes.

When Did Food Banks Become Corporations?

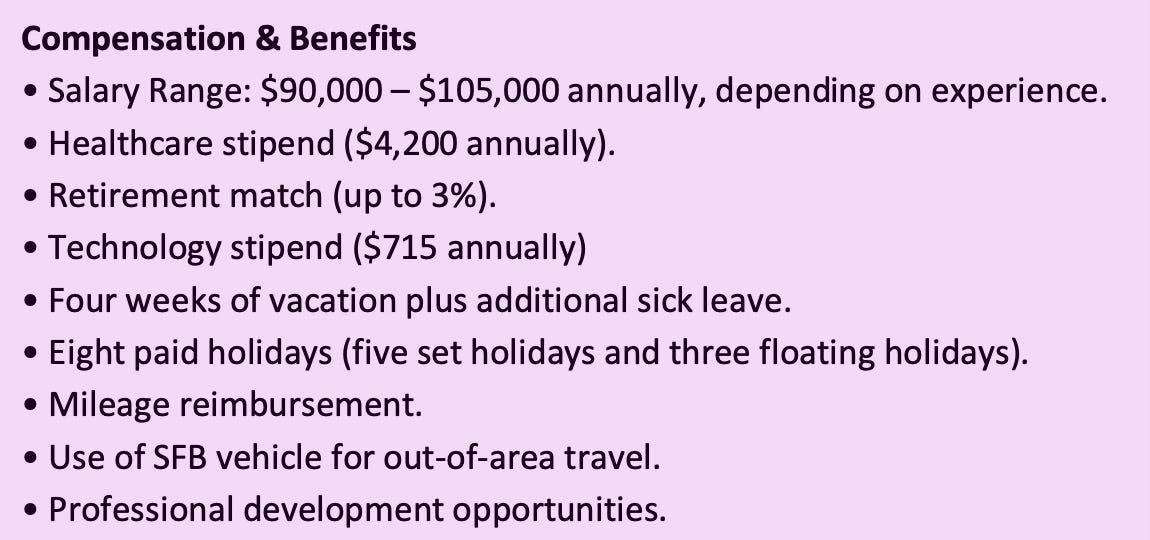

The Sequim Food Bank is searching for a new executive director — with a posted salary of $90,000–$105,000, extensive credential requirements, and responsibilities more consistent with a mid-sized corporation than a volunteer-driven charity.

Claiming to serve roughly 35% of the local population, the organization now seeks leadership with five years of executive nonprofit experience and a bachelor’s degree.

Many residents are asking a fair question: when did “donate food, distribute help” become a professionalized administrative enterprise — and who is this model really serving?

Ceremony, Spending, and No Public Comment

Clallamity Jen’s new publication, The Sequim Monitor, opens with a sharp, detailed account of Sequim City Council’s final meeting of the year.

Eight minutes of ceremony. Cedar roses. Standing ovations. Emotional tributes.

Then, quietly, hundreds of thousands of dollars in new spending — including a $233,000 increase in a criminal justice contract based on incomplete data.

“I’m just going to be really Indian for a few minutes, sorry.” — Outgoing city councilwoman Vicki Lowe

No public comment. No open discussion. Just praise, process, and adjournment.

It is well worth reading in full, and subscribing to the new Sequim Monitor, it’s free.

A Small Thank-You, With Big Meaning

Finally, a genuine thank-you to the very tall Watchdog reader who took the time to promote CC Watchdog on a local grocery store community board.

Word is spreading. Engagement is growing. And if the last year has proven anything, it’s that local accountability still matters — especially when citizens refuse to look the other way.

2026 is shaping up to be an important year.