The louder you shout, the more Clallam County Commissioners listen — especially if your resume includes “climate activist,” “Earth Law Center,” or “rights of nature.” Meanwhile, the people who actually live, work, and pay taxes here are lucky to get three minutes at a microphone. From timber policy to water rights, our local leaders seem more interested in entertaining activist lectures than hearing from the public they serve.

The New Inner Circle

Last month, the County Commissioners gave climate activist and self-proclaimed police abolitionist Brel Froebe a two-hour platform to argue for removing prime DNR timberlands from the harvest schedule. Appearing via Zoom, Froebe still got a premium seat with the commissioners. Supporting him in the boardroom was Elizabeth Dunne, an attorney with the Earth Law Center, who led the legal charge to stop logging on 300 acres in the Elwha watershed.

That lawsuit — filed by Dunne’s group and the Legacy Forest Defense Coalition — temporarily halted road building and timber sales, claiming DNR’s work threatened salmon habitat and endangered orcas. It also proved something else: when the threat of litigation is in the room, county officials listen.

Ordinary citizens? Not so much.

Meet the Power Duo: Dunne & Schromen-Wawrin

Dunne isn’t just another environmental lawyer. She’s part of a national movement that pushes “rights of nature” — the idea that ecosystems should have legal standing in court, just like a person. Before showing up in Port Angeles, she and outgoing Port Angeles City Councilmember Lindsey Schromen-Wawrin worked together in Pennsylvania for the Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), representing Grant Township in its fight against a fracking wastewater well.

That fight made national headlines — not for its success, but for its courtroom sanctions.

In 2018, a federal judge fined CELDF attorneys $52,000 for filing frivolous and repetitive claims. Dunne was named in the sanction order. Schromen-Wawrin was part of the same legal team.

Now both are here, shaping Clallam County’s policies — Dunne from the environmental side, Schromen-Wawrin from the political side.

Schromen-Wawrin, an outgoing Port Angeles City Council member, has spent years promoting the same “rights of nature” framework locally. Just this summer, he presented “Water Law in Washington: Who Owns the Water and What Are Our Rights?” to the Dungeness River Management Team — a group led by Hansi Hals of the Jamestown Tribe and County Commissioner Mark Ozias.

These are different issues, far from Pennsylvania, but it’s the same playbook.

Activists Get the Agenda, Citizens Get the Timer

When the Revenue Advisory Committee met this week, the only public comment opposing the “Cash for Counties” pitch from Elizabeth Dunne came from Jake Seegers. He pointed out that activists’ claims about the Doc Holiday parcels being “legacy forests” overlook the fact that the area was logged 80 years ago.

He also reminded the committee that one of the activists in the room, Tim Wheeler, was documented on film defacing state property — removing DNR boundary markers during a protest.

“If we reward that kind of behavior, it’s going to keep happening,” Seegers said.

None of those activists faced charges, but that’s how things work in Clallam County: break the law or threaten litigation, and you get the mic.

Meanwhile, the Tribe Joins the Chorus

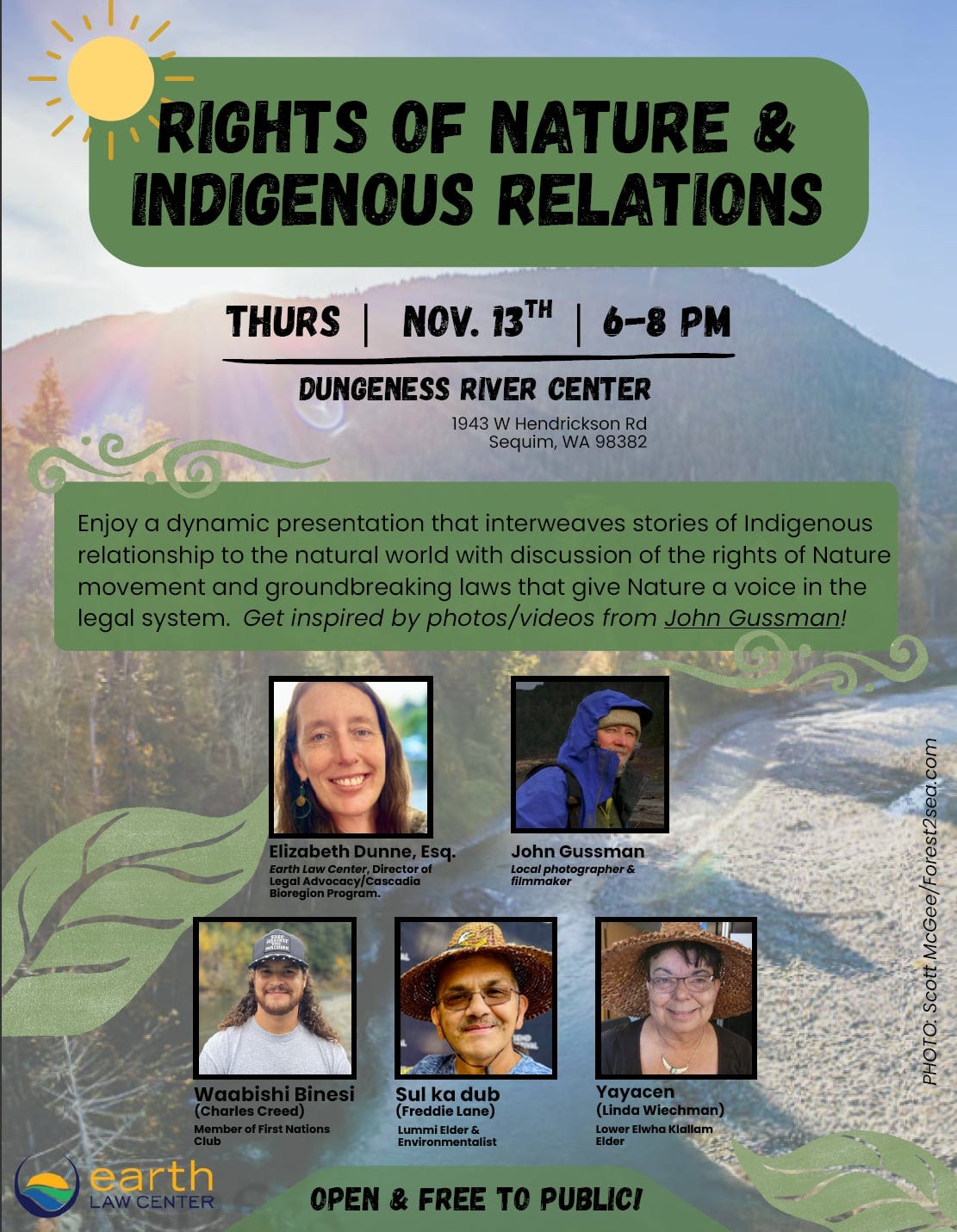

This Thursday, Dunne will present “Rights of Nature & Indigenous Relations” at the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Dungeness River Center — the same venue where Schromen-Wawrin gave his water-rights talk.

The Jamestown Tribe, Clallam County’s second-largest employer, continues to host and elevate the same small group of activists and legal advisors who are pushing state and county policies further toward regulation, restriction, and control.

It’s all happening while the average resident — the person trying to pay their taxes, keep their well, and hold onto their property — can barely get a word in.

Who Government Really Works For

There’s nothing wrong with experts having a voice. But when every “expert” invited to the table comes from the same activist circles, something’s not right.

• Brel Froebe, proponent for defunding the police, gets two hours.

• Elizabeth Dunne, who threatens litigation, gets 45 minutes.

• Lindsey Schromen-Wawrin gets a full presentation slot.

• Taxpayers get 180 seconds — if they’re lucky.

This isn’t public participation. It’s agenda management.

The Bigger Picture

This pattern — rewarding activism, ignoring dissent — is becoming Clallam County’s new normal. We’ve seen it with the push for a Water Steward by the League of Women Voters, in the Clallam Conservation District’s success in getting $2 million in additional funding, in forest policy, and now in public meetings that showcase the same few names over and over.

When the people running our county and cities decide that the loudest activists and outside attorneys are the “real stakeholders,” they stop serving the public — and start serving a movement.

Because if the goal were balance, transparency, or fairness, our leaders would spend less time scheduling presentations for people who’ve been sanctioned in federal court and more time listening to the people footing the bill.

It’s not just about who gets a seat at the table — it’s about who the table belongs to. And last we checked, that was supposed to be you.