County residents are waking up to the reality that “landback” is not just a symbolic slogan but a political and financial strategy already affecting local roads, farmland, and private property. From the closure of Towne Road to taxpayer-funded “buyback” programs, and from land trust partnerships to elected officials openly working to expand a sovereign nation’s land base, the question is no longer if the movement is here, but how much further it will go—and at whose expense.

The Landback movement, a national Indigenous-led push to reclaim ancestral lands, has taken root in Clallam County. Its language surfaced at tribal events such as the Lower Elwha Canoe Journey this summer, where “Landback” flags were flown. But beyond cultural symbolism, the movement has been woven into policy discussions, planning workshops, and county-level decisions.

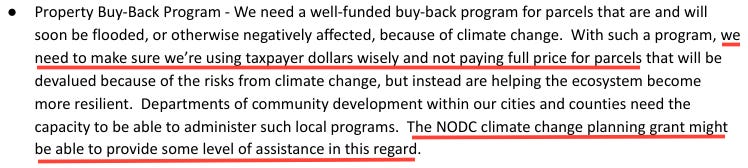

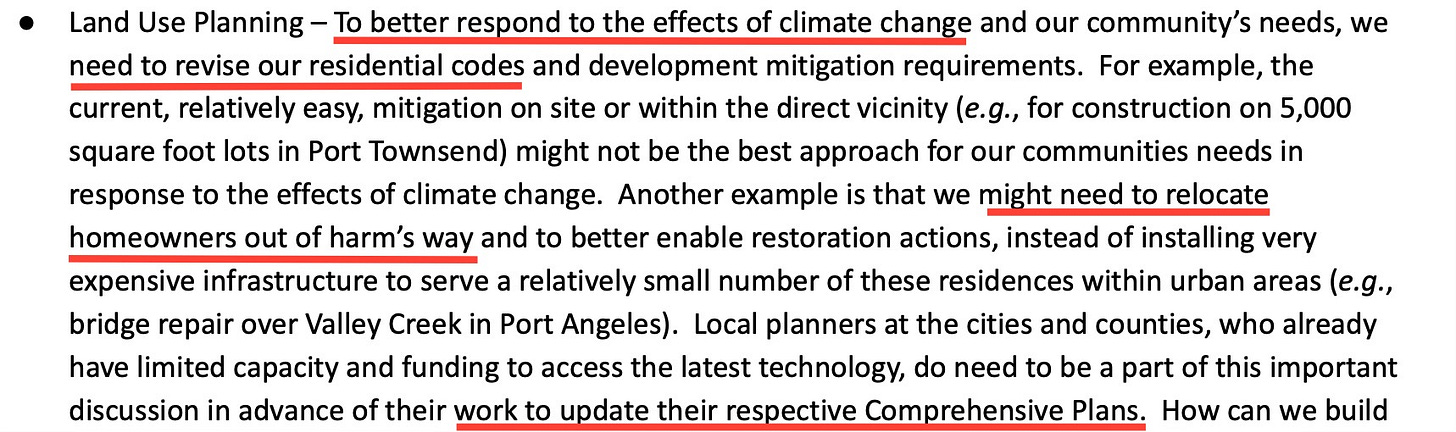

In 2021, the North Olympic Land Trust (NOLT) and the Strait Ecosystem Recovery Network (SERN)—whose fiscal agent is the Jamestown Tribe—hosted a workshop that included tribes, climate activists, and government agencies. The event suggested relocating property owners away from beaches threatened by sea level rise. Attendees openly admitted that property owners should not expect “full price” if their homes were bought out.

The workshop also called for leaning on elected officials in the 24th Legislative District to help implement these policies.

Politics and campaign cash

That recommendation was prophetic. Last year, Nate Tyler—an outspoken supporter of Landback—ran for the 24th Legislative District seat.

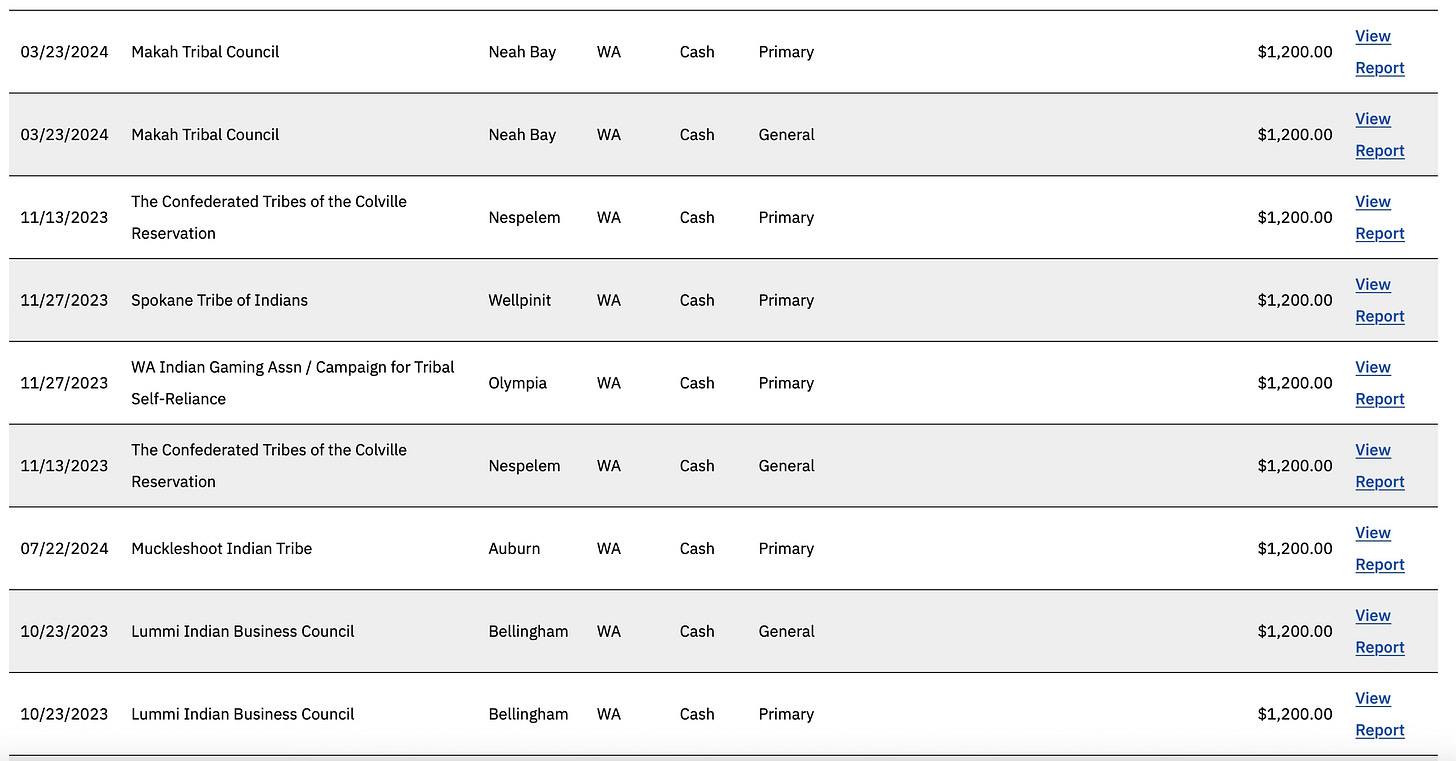

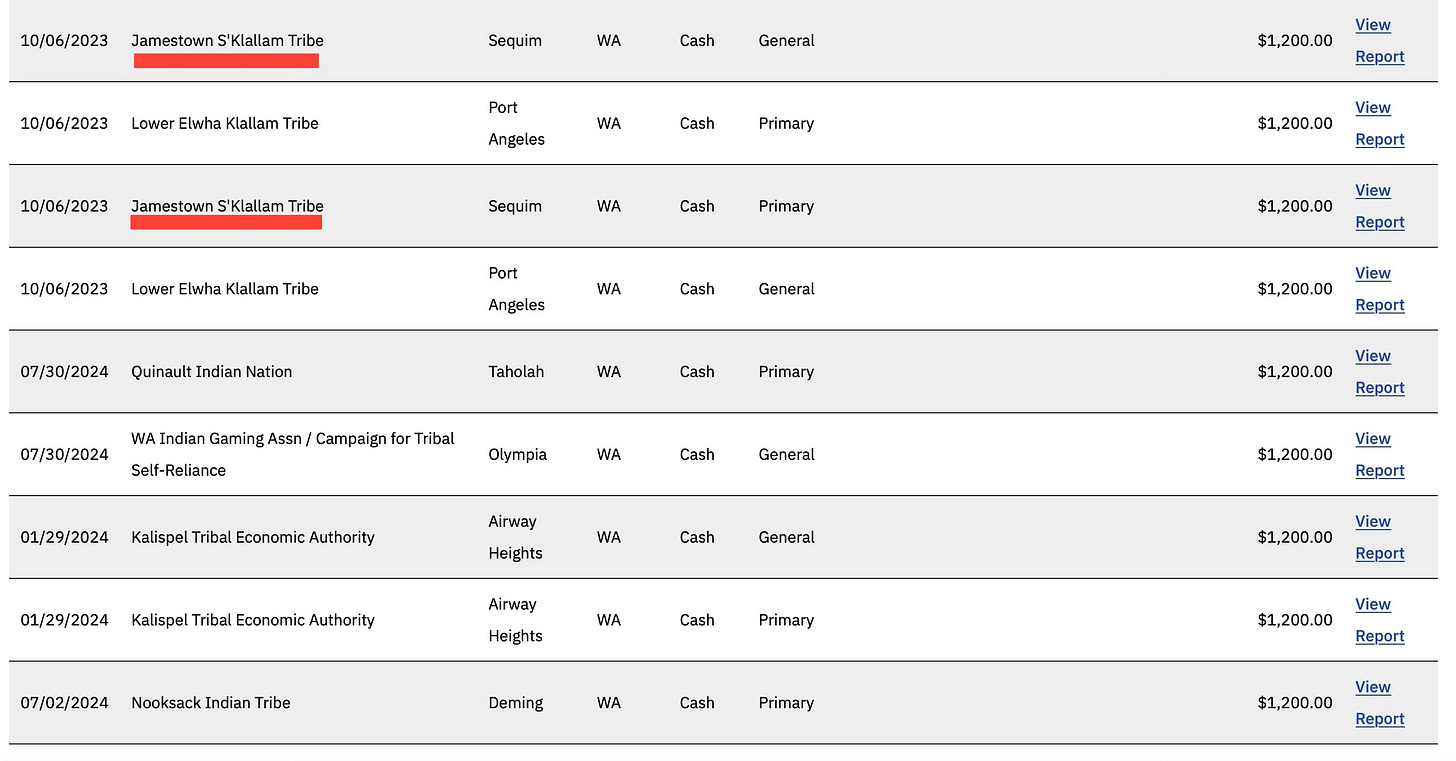

He raised more than $60,000, with his largest donors coming from tribal sovereign nations, including $2,400 from the Jamestown Tribe.

The same Jamestown Tribe that sponsored SERN’s 2021 workshop targeting coastal properties.

Tyler’s candidacy was endorsed by Commissioners Mark Ozias and Mike French, both of whom have since played roles in advancing policies aligned with Landback priorities.

County leaders speak plainly

Commissioner Mark Ozias has been unusually direct about his role. In a recent KONP radio interview, he said:

“Ideally, we can work toward a mutually acceptable agreement or understanding on how to consider the impacts of these trust conversions—what they mean for the Tribe, for their governance, and for fulfillment of creation of a land base for that Tribe and what it means for Clallam County.”

In plain English: our county commissioner has declared that expanding a sovereign nation’s land base is part of his job.

Meanwhile, commissioners have refused to answer the Department of the Interior’s inquiries about how much tax revenue is lost each time a property is converted into tribal trust land.

Remember that this November, when the County Commissioners ask voters to raise their property taxes.

The bluff-top playbook

The Jamestown Tribe’s 2016 Dungeness Drift Cell Parcel Prioritization and Conservation Strategy reveals a more systematic approach. The document identifies bluff-top properties between Morse Creek and Dungeness Spit, ranking them by erosion threat, development density, and—most controversially—the landowner’s “fear” and “desperation.”

One passage is blunt:

“Fear may turn to desperation, especially where the landowner does not own sufficient property to move the structure back from the bluff.”

The strategy prioritizes parcels where owners are “likely to be the most fearful” and therefore most willing to sell. These high-value properties, some with million-dollar views, become “opportunities” once erosion or restoration projects diminish their security.

The plan even weighs “cost-effectiveness,” calculating which parcels offer the most shoreline for the lowest property value. In short: who’s scared, and who’s cheap.

Three Crabs Road: “Retreat or removal”

The Landback strategy is not limited to high bluff parcels. The Marine Resources Committee (MRC), chaired by LaTisha Suggs — a Jamestown Tribal member, Port Angeles city councilwoman, and a current candidate for Port Angeles city office — sent a letter to county commissioners urging them to consider “retreat or removal” of roads and homes along Three Crabs Road after a joint tribal–county estuary restoration reportedly worsened flooding for nearby residents.

The recommendation mirrors the logic of the 2021 workshop: when erosion or environmental restoration is at stake, “retreat” becomes a policy option — usually funded through public dollars and nonprofit partnerships. In practice, that means talk of removing infrastructure falls hardest on homeowners already facing flood risks, left uncertain about who makes the decisions and who pays the price.

The MRC action shows how policy recommendations originating from committees with tribal leadership can quickly move from study to formal requests to the commission — raising questions about stakeholder balance, accountability, and who is most affected by the recommended outcomes.

Land trusts as partners

The Jamestown Tribe doesn’t act alone. Their documents outline partnerships with government agencies and nonprofits—including the North Olympic Land Trust.

NOLT has preserved more than 3,900 acres since its founding 35 years ago, but its recent projects have raised questions. In 2020, NOLT and the Tribe jointly purchased farmland between the Dungeness River and Towne Road. Donors believed Towne Road would be relocated atop the new levee as part of the Lower Dungeness Floodplain Restoration Project. Instead, the Tribe breached the old dike, causing the Towne Road closure, and then they fought to keep it closed.

Many donors feel misled. One supporter put it this way:

“I donated to NOLT to preserve land based on levee and restoration plans that included moving Towne Road up and out of the flood plain. It never occurred to me that NOLT’s partner in the project would intentionally sabotage the planned movement of Towne Road.”

Another donor, equally disillusioned, said:

“I am no longer supporting NOLT. They say they don’t get involved in politics, but their partnerships tell a different story. I’ll be more careful about which projects I donate to in the future.”

Conflicts of interest

Leadership overlaps amplify concerns. Wendy Clark-Getzin — president of NOLT during the relocation of Towne Road — was also the Transportation Program Manager for the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. She, in her tribal role, advised the county to convert the road into an “outdoor classroom” and leave it incomplete.

At that time, Clark-Getzin was also the vice-chair of the county’s Trails Advisory Committee (TAC). Under Commissioner Ozias’ suggestion, the TAC voted to halt the completion of Towne Road, a decision that ran counter to recommendations from the County Engineer, County Biologist, Director of Community Development, Department of Ecology, Army Corps of Engineers, the Sheriff, two fire chiefs, the State’s Tsunami Program Manager, and the county’s engineering consultant. Commissioner Ozias cited the TAC recommendation in opposing reopening the road — a move critics argue favors tribal goals over broad public safety and access.

But Clark-Getzin isn’t the only overlap. Commissioner Ozias himself serves as president of the North Olympic Development Council (NODC), an NGO funded by taxpayers that influences Clallam County’s Comprehensive Plan. According to SERN, the NODC would assist in seizing property at below-market prices.

The NODC, led by President Ozias, plays a quiet but powerful role in shaping the County’s Comprehensive Plan — the document that dictates land use and code for decades. At a SERN workshop, participants emphasized that revising these plans would be critical to advancing climate-change policies, including the potential relocation of homeowners.

In practice, this means a commissioner is leading an NGO that steers how Clallam’s Comprehensive Plan — the blueprint for land use for the next 20 years — will be written. Critics argue this arrangement hands unelected, grant-funded groups undue influence over land-use decisions while bypassing direct accountability to the public.

A shift in NOLT’s mission

At its 2023 “Standing Out in the Field” ceremony, NOLT opened with a land acknowledgment emphasizing the harms of colonization. Executive Director Tom Sanford went further, thanking commissioners for a new “conservation futures” property tax—another stream of public funding.

NOLT then gave its annual award to the Dungeness River Management Team, a joint venture of Clallam County and the Jamestown Tribe. Towne Road’s closure, a direct result of that partnership, went unmentioned.

What was once a grassroots, non-political land trust has become a conduit for controversial policies, leaving longtime supporters disillusioned.

How Much Is Enough?

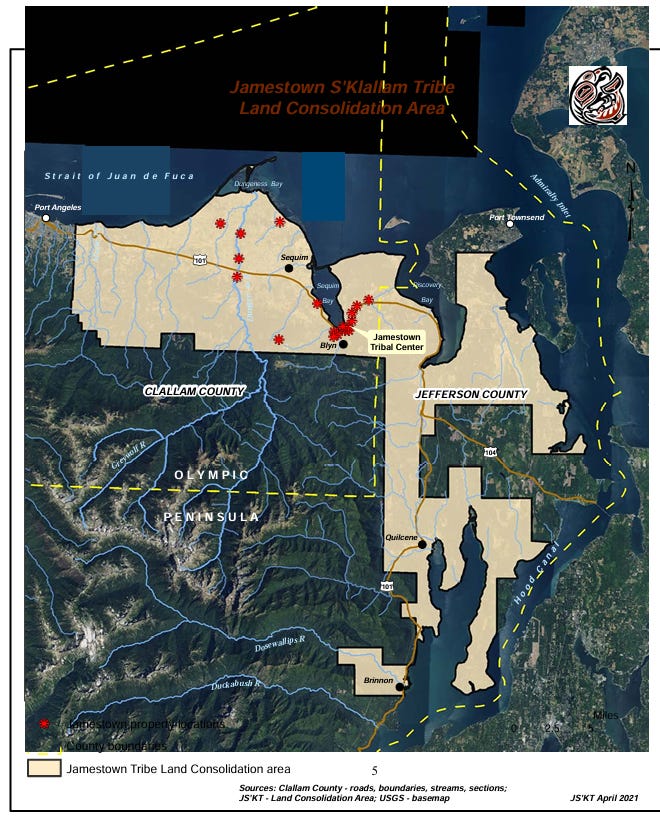

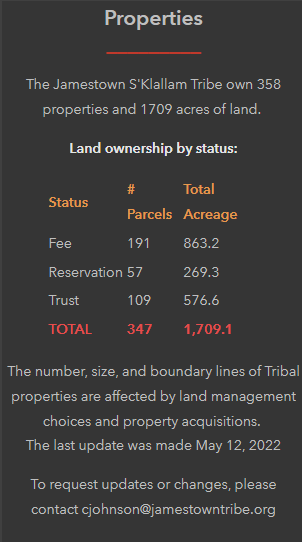

According to its most recent figures, the Jamestown Tribe holds 1,709 acres. With 209 members living locally, that equates to eight acres per every man, woman, child, and infant. Commissioner Ozias has openly declared his goal is to expand that land base further.

The question for Clallam County residents is simple: how much is enough?

Landback in Clallam County has shifted from cultural revival to actionable policy — already reshaping roads, neighborhoods, and private property. Public officials and nonprofits owe taxpayers straight answers about funding, intent, and accountability. Until then, residents are left to wonder whether they are being asked to bankroll restoration, retreat, and territorial expansion — and who truly benefits when public power, private donations, and sovereign interests converge.

When fear, desperation, and political alliances dictate land policy, property owners cease to be participants; they become targets. The steady advance of Landback in Clallam County shows that the line between cultural restoration and political capture hasn’t just been blurred — it has been crossed.