157 years ago, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe helped erase entire tribes, stole their wealth, and later bought their own land base with gold coins. Today, county commissioners claim the Tribe “did not begin with a land base” as they hand over more property, remove hundreds of thousands from the tax rolls, and shift the burden to local families. This Flashback Friday, we connect the dots between a bloody past and a modern betrayal: when elected leaders put a sovereign nation ahead of the people they swore to represent.

This Flashback Friday we look back 157 years, to a September night in 1868 on the Dungeness Spit.

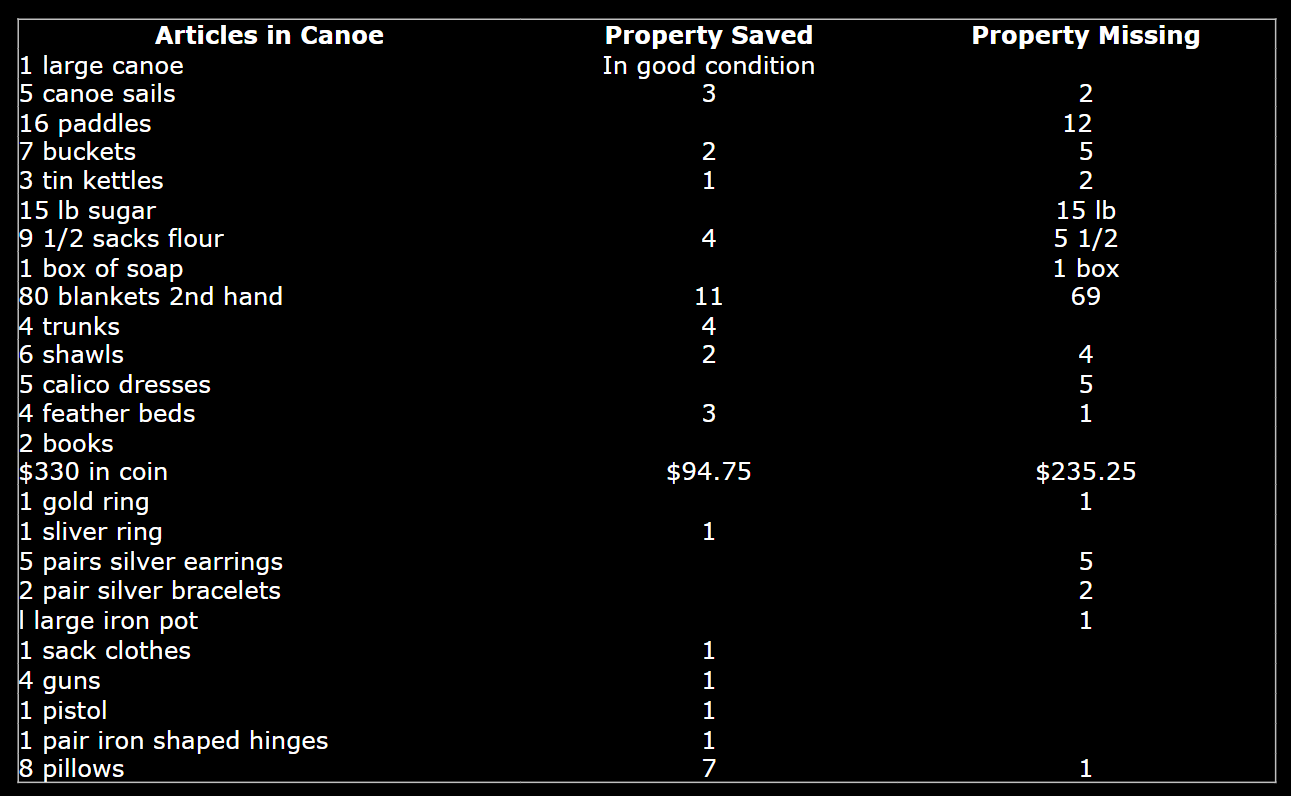

A historylink article tells the story: A party of 18 Tsimshian Indians, returning home to Prince Rupert, B.C., after picking hops in Puyallup, stopped to rest and wait for the fog to clear before making the 22-mile crossing of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. That night, they were attacked. A group of Jamestown S’Klallam crept up on the camp, collapsed the shelter, and in the chaos killed 17 Tsimshians—10 men, 5 women, and 2 children—using knives, clubs, and guns. The raiders looted the camp, stripping valuables and carrying off souvenirs.

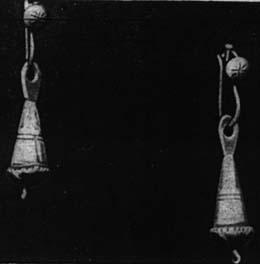

There was only one survivor: a 17-year-old pregnant woman named Nusee-chus (or Chichtaalth), left for dead after being beaten, stabbed, and robbed of her jewelry. We know from her testimony that hundreds of dollars in gold coins were taken that night.

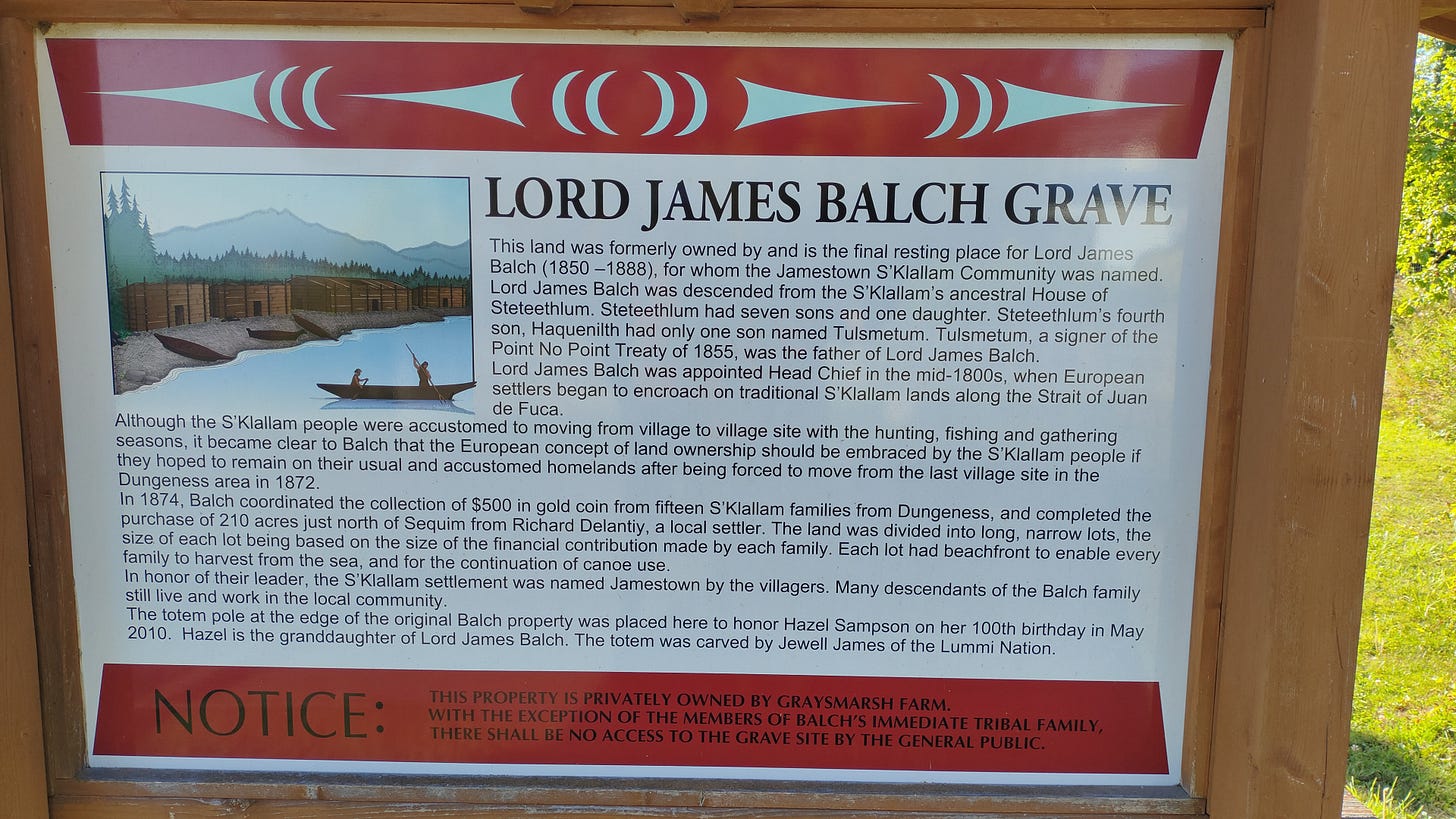

Just six years later, in 1874, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe purchased 210 acres on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Fifteen families, led by Lord James “Jim” Balch, pooled $500 in gold coins to secure the land. This purchase was bold, even visionary—By buying land, they carved out independence, establishing Jamestown, Washington.

That land purchase became the Tribe’s land base. It was a symbol of sovereignty, resilience, and survival.

And yet, fast-forward to today, and we are told by our county commissioners that the Jamestown Tribe “did not begin with a land base” and must build one now by transferring property into federal trust. Commissioner Mark Ozias even wrote that the Tribe is “building the land base to which they are entitled.” But history tells us something different: they already had one. They owned land, they sold land, and now they want more—this time without property taxes.

What about the Chimakum?

If we’re talking about “building land bases,” maybe we should ask: what about the Chimakum people?

The Chimakum (or Chemakum) once lived in East Jefferson County, including the fertile Chimacum Valley. They spoke their own language, related to the Quileute. But by the early 1800s, the Chimakum were nearly wiped out.

According to historians and oral accounts, the S’Klallam and Suquamish tribes, led in part by Chief Seattle, launched a coordinated raid against the Chimakum. The attackers ambushed families, overwhelmed the village, and destroyed the tribe as a distinct people. Survivors were absorbed into other groups.

Today, Chimakum descendants are enrolled in tribes like the Skokomish, Jamestown S’Klallam, and Port Gamble S’Klallam. But as a people, the Chimakum were erased—largely at the hands of those now claiming victimhood in land disputes.

So before we accept the narrative that today’s S’Klallam “did not begin with a land base,” maybe we should remember what they did to the Chimakum’s land base. Where is the call to restore land for the Chimakum?

The numbers don’t lie

According to the County Assessor website, the Jamestown Tribe owns 349 parcels in Clallam County (information from March 30th, 2025). Of these, 153 pay no or minimal taxes, including a golf course, the MAT clinic, Jamestown Family Health Clinic, a tribal library, and private residences.

Those tax-exempt parcels have an assessed value of nearly $44 million. If taxable, they would generate over $340,000 annually for county services. Instead, they pay just $5,561—a 98% discount. Yet when KONP reported on this issue, the county framed the loss as just $19,000 in recent transfers—conveniently minimizing the true impact.

Who do commissioners represent?

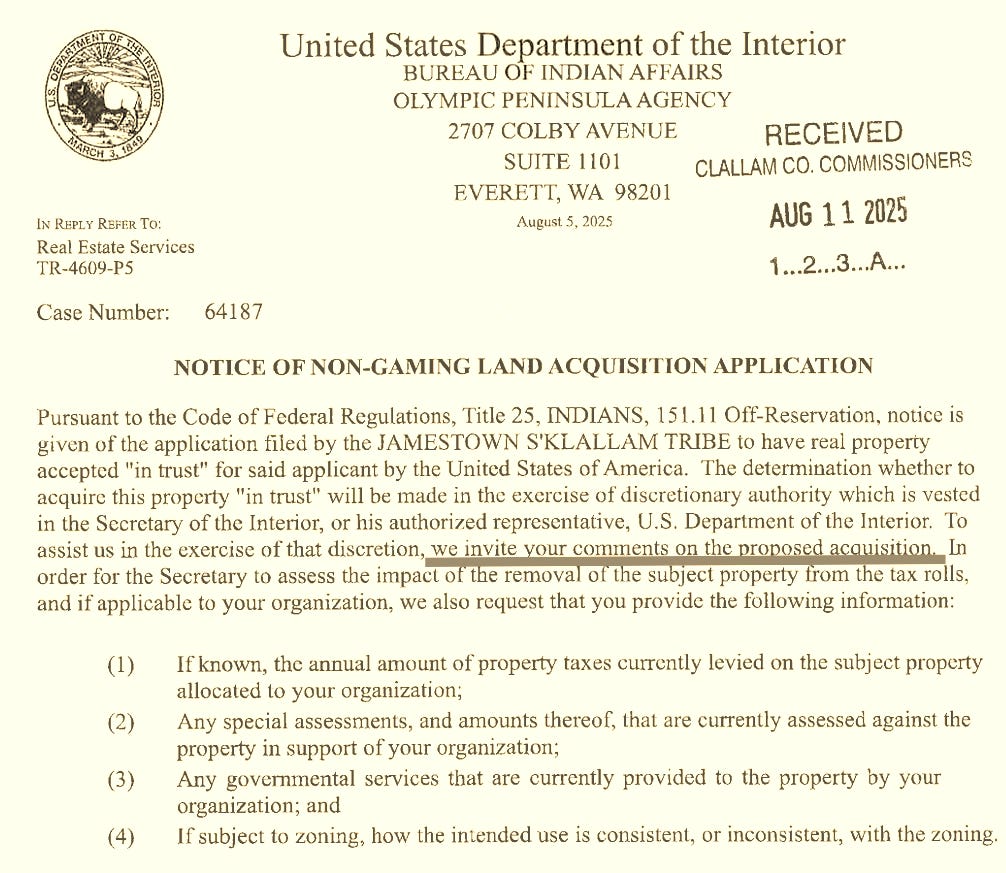

And this isn’t theoretical. This month, the Bureau of Indian Affairs formally notified the Board of County Commissioners that the Jamestown Tribe has applied for two additional parcels to be converted into trust status. The BIA has specifically invited the commissioners to comment on the impact these conversions will have on our already economically depressed county. Yet they have not submitted a single objection—or even raised a question—in at least a decade.

This silence is not neutrality—it’s complicity. When our commissioners admit in writing that they “refrain from commenting,” it’s not caution or restraint. It’s a deliberate policy of silence that favors the Tribe’s agenda over the people they were elected to represent.

Think about that. Our elected commissioners openly admit they withhold comments to the federal government because they “support” the Tribe’s expansion. But they are not elected to represent the Tribe. They are elected to represent the people of Clallam County—the very people now being asked to pay more in property taxes to make up for the lost revenue.

And Commissioner Ozias has gone even further. Last April, during the Towne Road relocation controversy, he offered a public apology—not to his constituents, but to the Jamestown Tribal Council. His words:

“So, to the Jamestown Tribal Council and members of the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe, I'd like to take this moment to apologize for my lack of communication. I believe that the Jamestown S'Klallam Tribe is our most important partner in local governance whether we're talking about healthcare, or habitat restoration, or transportation, or emergency management, or economic development, or any of the myriad of areas that we work together for this community, and I hope to do better in meeting that standard in the future."

The most important partner? What about the three other tribes in Clallam County? What about the small businesses that generate our tax base? What about the families paying thousands in property taxes just to stay in their homes?

How did the “most important partner” become the one skipping out on taxes?

Is this representation? Or is it capitulation to a sovereign government that already has its own leadership and its own representation in Washington, D.C.? Would we tolerate this if they were supporting land acquisitions by Costa Rica, Canada, or any other sovereign nation?

A question of fairness

The Tribe has 209 local members and reported nearly $86 million in revenue last year. Does a sovereign nation with that kind of wealth truly need Clallam County’s elected commissioners lobbying on its behalf? Meanwhile, ordinary taxpayers—people like you and me, possibly living on our own ancestral homeland—face crushing property tax bills just to stay in our homes.

If my family sold most of our farm over the years, do I now get to demand the county “rebuild” my land base? Do I get to stop paying over $10,000 in property taxes for my 3.1 acres while expanding my holdings? Of course not.

So why do our commissioners treat the Tribe differently?

The weaponization of guilt

History is complicated. Land has changed hands for centuries—sometimes by conquest, sometimes by sale, sometimes by law. The Jamestown Tribe chose to buy land in 1874, and they owned it. Different members later sold it, just as my family did—my great grandparents took our farm from 160 acres down to just eight. Now it’s three. That’s history.

What’s new today is the use of guilt as a weapon to reclaim land—this time without conquest, but through political influence, campaign donations, and compliant local leaders.

The Jamestown Tribe funded 53% of Commissioner Ozias’s last campaign. Is it any surprise his letter prioritizes the interests of a sovereign nation over ours?

The growing burden

Every acre transferred into trust is another acre removed from the tax rolls. Every acre removed from the tax rolls is another burden placed on struggling families, farmers, and small businesses. And every time our commissioners choose silence in order to “support” the Tribe, they choose loyalty to a sovereign government over the people who elected them.

This November, Clallam County voters will be asked to raise their own taxes yet again. Before we vote, we should ask: Who do our commissioners really represent?

The emails

Dear Commissioner Ozias,

I am writing to follow up on the property tax figures you provided regarding Jamestown Tribe trust land transfers.

According to information I collected from the County Assessor’s page, the Jamestown Tribe currently owns 349 properties in Clallam County. Of these, 153 parcels (43%) pay no or minimal taxes. These properties include a golf course, the MAT Clinic, Jamestown Family Health Clinic, Tribal Library, and private residences in Sequim and Port Angeles.

The cumulative assessed value of the 153 tax-exempt properties is $43,949,361. (Because valuations are frozen at the year parcels are converted into trust, the true figure is likely much higher.) If these properties remained taxable, the county would be receiving approximately $342,715 annually in property tax revenue (also a lowball figure since the valuations are frozen). Instead, the Tribe and its corporate entities are paying just $5,561 annually — effectively a 98% property tax discount compared to their competitors.

This does not align with what was reported in myclallamcounty.com, where county officials were quoted as saying that “recent Jamestown trust land transfers represent more than $19,000 in lost annual property tax revenue on parcels valued at over $2.1 million.” The article framed this as an annual revenue loss, not a “year to date” figure as you suggested during public comment.

I understand that you may have been referencing only the “recent” trust land transfers, but what qualifies as “recent”? And why would the county provide information limited to only those parcels — when the broader issue involves over 150 parcels and hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost tax revenue every year?

For context, my property tax bill for a single-family home on 3.1 acres exceeds $10,000 annually. To present the public with the impression that the Tribe, holding over a thousand acres across the county, pays only twice that amount is misleading.

This issue is especially important now, as voters will soon be asked to consider raising their own property taxes to fund essential county services. If the public is told the county is “only” missing $19,000, when in fact the true figure is exponentially higher, that fundamentally alters the discussion.

Could you please clarify the following:

What time frame you were referring to with the $19,000 figure.

Why the county is not presenting the full scope of tax-exempt tribal holdings when asked about this issue.

Whether the county has performed a comprehensive analysis of the total annual revenue loss from trust land conversions in Clallam County.

The public deserves transparency on the true financial impact.

Thank you for your time, and I look forward to your clarification.

Appreciatively,

Jeff Tozzer

Mr. Tozzer,

I can’t speak to how others may have characterized the information. The Assessor’s Office recently shared a list of the transfers this year to-date, which is what was included in the agenda packet and was intended to serve as one point of reference – not the only point – for this conversation.

As I stated in our work session conversation, it is important to note that unlike other area Tribes, the Jamestown S’Klallam did not begin with dedicated acreage and/or a land base for a reservation; rather, they are building the land base to which they are entitled by federal law to have.

The County Administrator has been compiling information on all of the non-taxable land in the county which will also help to inform this conversation moving forward so that it happens with as much context as possible.

Mark Ozias