Clallam County is spending millions to make drug use “safer”—handing out crack pipes, boofing kits, and Plan B while overdose deaths continue to climb. A public health model shaped by radical ideologues and tribal politics now dominates policy, but with little evidence that it's saving lives. The people, priorities, and power behind this system are more focused on “honoring the land” than holding anyone accountable.

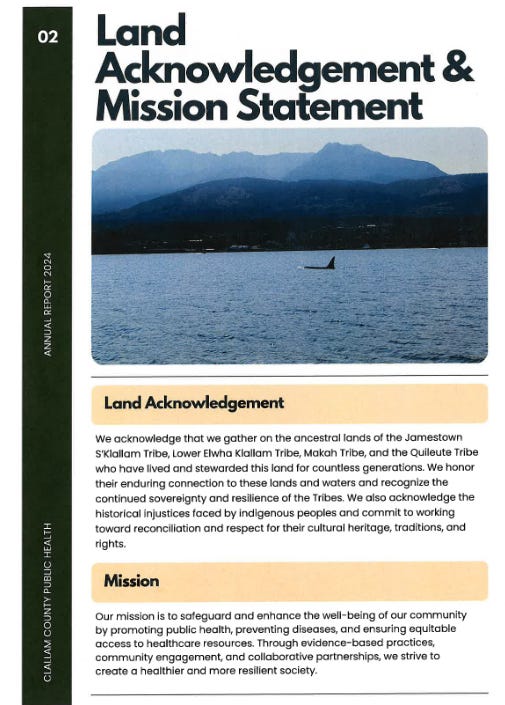

Clallam County’s 2024 Public Health Annual Report opens not with a mission statement or public health priorities—but with a land acknowledgment. Before addressing overdose deaths, access to care, or taxpayer spending, your county government pauses to recognize the ancestral lands of four local tribes.

The acknowledgment reads like a solemn tribute to stewardship and historical injustice. But what does it say about a county facing record-breaking overdose deaths, a public health department distributing pipes and boofing kits, and taxpayer-funded programs run by ideologues who came from radical organizations?

“Honoring the land” – but at what cost?

The first words of Clallam County’s 2024 report read:

“We acknowledge that we gather on the ancestral lands of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe... We honor their enduring connection... and recognize the continued sovereignty...”

This reverence stands in stark contrast to the historical record. The Klallam Tribes, including the Jamestown band, practiced slavery and committed documented acts of violence against other tribes, like placing their enemy’s heads on poles. In one 19th-century incident, 17 travelers were massacred on the Dungeness Spit, and $500 in gold coins were stolen. Yet today, their revenues top $86 million for about 209 local members, and the tribe continues to expand commercial holdings—a golf course, gas station, and cannabis shop—while also lobbying for aggressive water and land use policies that raise costs for rural residents.

So why is a public health document leading with a cultural endorsement of a casino empire rather than a strategy to save lives? It may depend on who benefits from solving an addiction crisis.

Harm Reduction: Pipes, Foil, and Plan B

The phrase “harm reduction” has become shorthand for Clallam County’s drug response. In practice, this means if you’re addicted to fentanyl, the county won’t arrest you, they’ll help you use it—more safely.

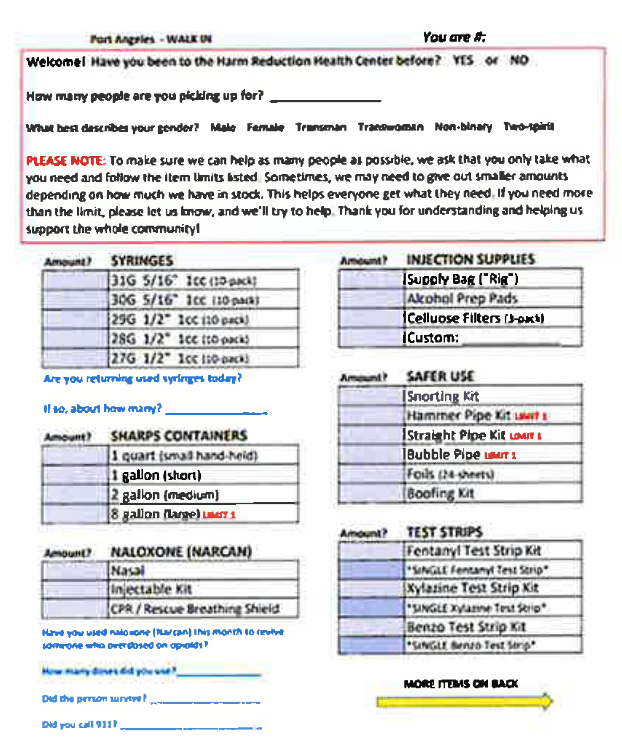

At the county’s Harm Reduction Center, a walk-in participant can select from a veritable menu:

Needles (multiple gauges)

Foil and pipes (hammer, straight, and bubble, limit one per customer)

Narcan (nasal and injectable)

Alcohol prep pads

Boofing kits (for rectal administration)

Fentanyl test strips

Snorting kits

But the offerings don’t stop with drug use tools. The county also provides:

Condoms, lube, dental dams

Plan B kits

Nicotine gum, mouthwash, floss

Protein drinks and cough drops

Deodorant, gloves, combs, hats

All of this is funded in part by taxpayer dollars and opioid settlement funds—without any clear accountability for outcomes. The center, located in downtown Port Angeles, pays $4,000 per month in rent.

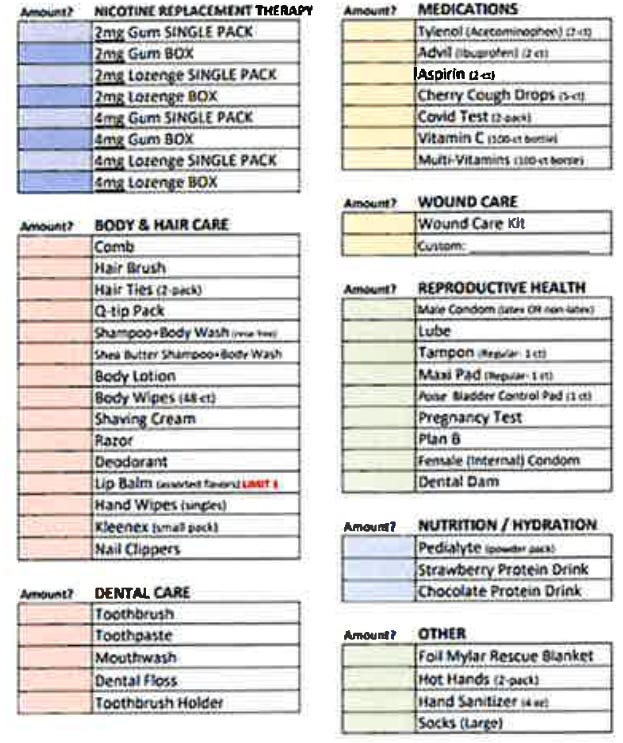

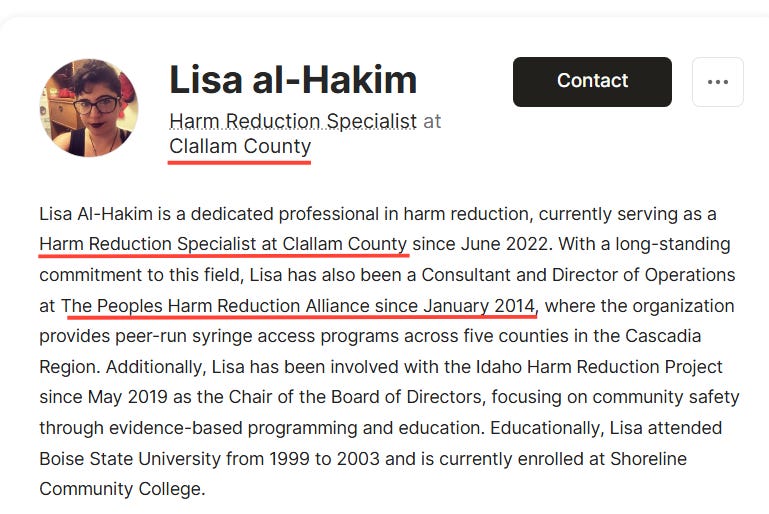

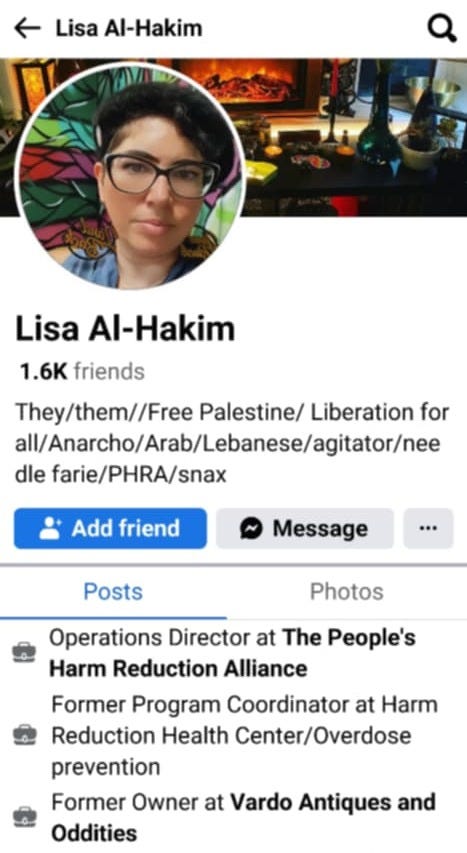

Lisa Al-Hakim: Architect of the system

Much of Clallam’s harm reduction policy appears rooted in the ideology of Lisa Al-Hakim, a former county employee who called herself an “Anarcho-Arab.” After her car—nicknamed the “needle farie”—was stolen in Oregon, Clallam County bought her a new van to distribute needles, foil, and pipes across the West End. That program continues today.

Al-Hakim left Clallam to return to her position as the Operations Director of the People’s Harm Reduction Alliance (PHRA)—a group that explicitly opposes addiction treatment. PHRA describes itself as “unapologetically in support of drug users,” and their director has publicly stated they “refuse to be complicit in the death of our community members by sending them to treatment that doesn’t work.”

The PHRA describes their philosophy as a “drug user union.” PHRA Director Shilo Jama, who has been using drugs since his teenage years, explains the harm reduction model of PHRA promoted by Al-Hakim in this interview.

In a 2019 article in The Stranger, PHRA was praised for distributing supplies regardless of legality. In another post, Al-Hakim described herself as a “freedom fighter,” opposing restrictions on drug use as forms of oppression.

This is who Clallam County hired as a Harm Reduction Specialist. Is it any wonder that the programs she helped implement in Clallam reflect those same values?

Record overdoses, record spending

Despite the resources poured into harm reduction, Clallam County has not turned the tide. According to Clallam County Prosecutor Mark Nichols, the county ranked third in Washington State for overdose deaths last year, with 59.3 deaths per 100,000 residents from June 2023 to June 2024. The county saw 27 overdose deaths in the first half of 2024 alone, putting it on track to break or match the previous year’s grim record.

Nichols notes that fentanyl is a key driver, “Suffice to say that’s a crisis-level challenge,” said Nichols on KONP’s Todd Ortloff Show.

The public, meanwhile, wonders how much of this is really helping. One local listener summarized the skepticism: “So tell me again how this is working?”

The County responds: A seatbelt for drug use?

In a recent KONP radio interview, Clallam County officials including Jenny Oppelt, Siri Sims, and Commissioner Mark Ozias defended the harm reduction model.

Oppelt compared harm reduction to seatbelts and sunscreen, claiming the goal is to build “trusting relationships” with addicts in hopes that someday they’ll seek treatment.

Ozias called the strategy “evidence-based” and said the Board of Commissioners stands behind it. He stressed that funding comes from “Foundational Public Health Services” and opioid settlements—not local tax increases. But he also noted that 1 in 5 Clallam County residents suffers from addiction—a claim hard to believe.

When asked if the program was enabling drug use, Oppelt replied, “When we can’t force them to stop, we keep them safe as possible so they can hopefully change when ready…”

But no data was offered to show how many actually do seek treatment, how many recover, or how many overdosed despite “supportive” services.

Private harm reduction in public parks

Perhaps most concerning, the culture of harm reduction has expanded beyond official government programs. In Port Angeles’ Jessie Webster Park—known locally as “Tree Park” behind Swain’s—a private citizen openly advertises on Instagram that drug supplies are distributed there weekly.

Photos confirm the activity.

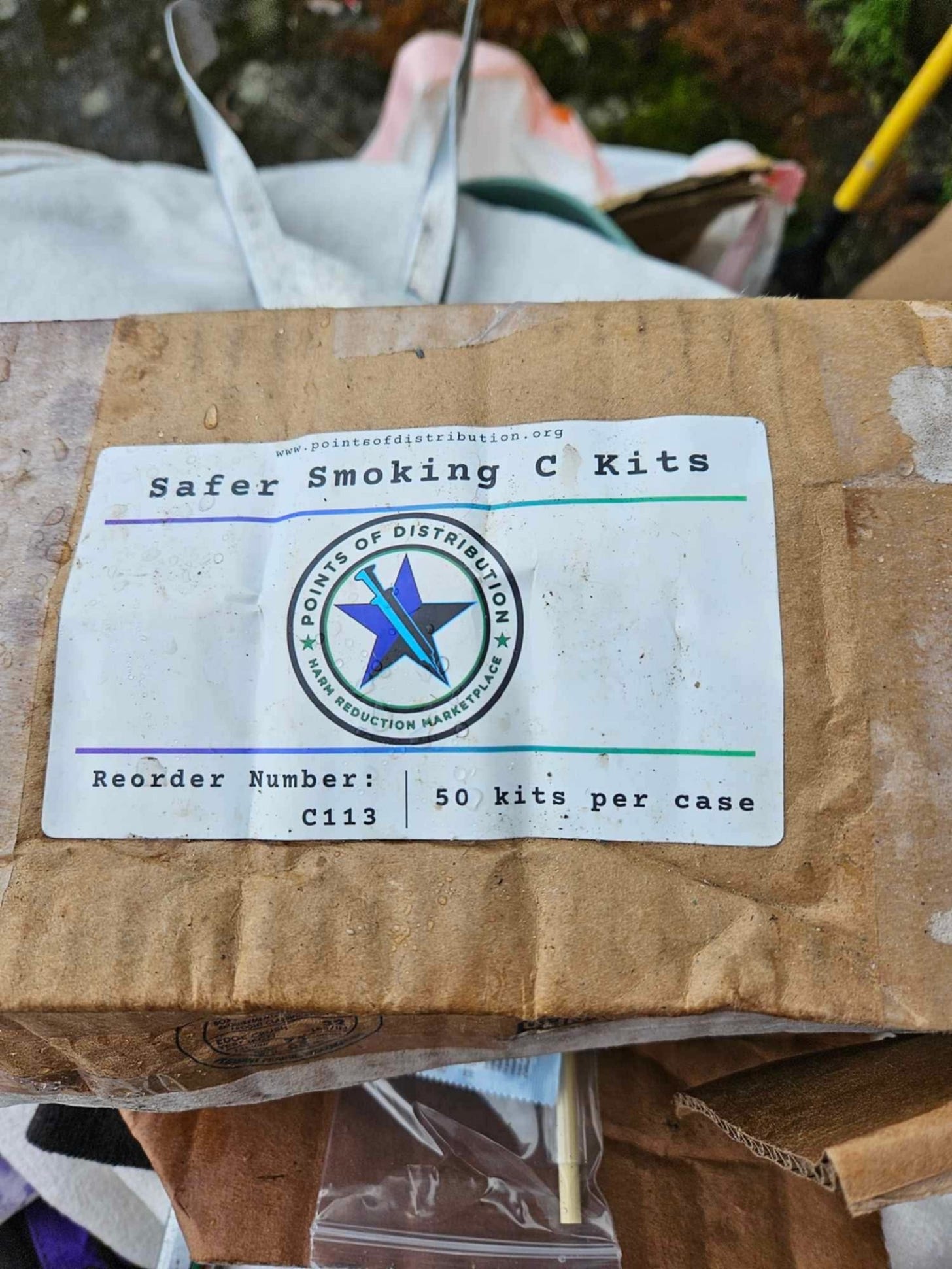

One resident recently found a discarded shipping box labeled for “Clallam County MASHR” on Race Street.

It had been mailed to a private home in Sequim and was marked as containing “safer smoking C kits.” The box was one of 18 in the shipment and contained 50 kits.

Alongside the smoking kits were other supplies.

The incident underscores growing concern that a private citizen, in a public park, is operating in place of official public health channels—distributing paraphernalia with no oversight, while county officials look the other way.

Compassion or collapse?

Clallam County’s health officials may see themselves as compassionate, progressive, and rooted in equity. But the numbers don’t lie: overdoses are up, spending is up, and accountability is absent.

The harm reduction model may offer dignity and warmth—but at what cost to public safety, community standards, and real recovery?

Perhaps it’s time Clallam County residents asked a different question—not how to make drug use safer, but why our public health system is making it easier in the first place.

Last Sunday, readers were asked how they felt about this statement: Identity politics is dividing our community more than it’s helping it. Of 258 votes:

91% strongly agreed

7% somewhat agreed

0% somewhat disagreed

2% strongly disagreed