The Canoe Journey is a powerful celebration of Indigenous culture—but this year’s landing at Jamestown Beach highlights a deeper issue. While the Tribe isn’t required to get permits or pay fees, local groups hosting similar events must navigate costly red tape. If cultural heritage matters to all, why are there two sets of rules? Dive into the double standards—and calls for equity.

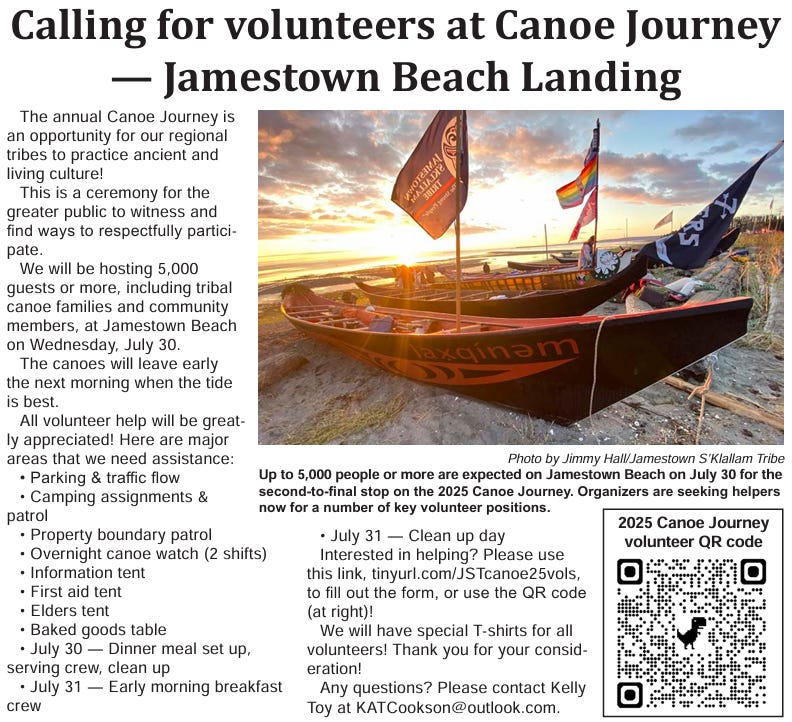

It’s hard not to be moved by the annual Canoe Journey. If you’ve seen it, you know: tribal canoes arriving from across the Northwest, welcomed with song, ceremony, and food. It’s a celebration of culture, tradition, and family—one that’s been happening for decades up and down the Salish Sea. This year, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe is hosting the landing at Jamestown Beach, and it’s going to be huge.

The tribe expects around 80 canoes from Washington, Alaska, and Canada to land on their beach this summer, with an estimated 5,000 people attending for an event that lasts less than 24 hours. They’ve been working hard to get their beautiful new pavilion and grounds ready. But with only a few hundred feet of tidelands, they’ve also had to reach out to neighbors for help.

“If you are willing to allow canoes to sit on your beach overnight, we would be very appreciative,” reads a letter to Jamestown Beach residents.

When asked if the Tribe would be getting a permit for the event, Vice Chair Loni Greninger replied by email:

“No permits have been required as these are annual cultural events and we coordinate with the Sheriff’s office for health and safety purposes, even though it is on tribal land. We definitely value the partnership since the public is invited to this event.”

And to be clear, yes—tribal sovereignty means they don’t need a permit from the county for what happens on their land. But parts of this event aren’t just on tribal land. The Tribe is asking to use neighboring private property, beaches, and tidelands.

What would happen if anyone else tried to host something like this?

What the County requires from everyone else

Clallam County’s rules are clear: if you’re hosting a public event, you need a permit. That applies to concerts, festivals, cultural celebrations—anything open to the public. And it’s not just red tape; it’s expensive and time-consuming.

For large events—over 1,500 people, amplified music, lasting more than three hours outdoors—you need a Festival Permit. That means:

A $2,500 permit fee

Site maps, insurance, emergency planning

Approval from the Sheriff, Fire Marshal, Health Department, Public Works, and the County Commissioners

A public hearing

Inspections before and during the event

Potential denial or revocation if rules aren’t followed

If your event is smaller—say, just over 50 people—you still need an Assembly Permit, with a similar process and lower fees.

Now add food? That’s another permit. The Environmental Health permit costs:

$105 to $210 per vendor, depending on complexity

Plus late fees (50% or more) if you miss the 10-day window

You’ll need water, waste, and toilet facilities on-site

Why this matters

If you or your church group or nonprofit tried to host 5,000 people for a cultural celebration on the beach, without permits, inspections, or formal approval—you’d be shut down. Or fined. Or both.

That’s not a knock on the Jamestown Tribe, who have every right to host this gathering and have done so with care and coordination. But the situation highlights a basic fairness issue: why are the rules so strict—and expensive—for everyone else?

County permitting exists for a reason: safety, health, crowd control, and fairness. But it’s hard to argue that those concerns disappear just because an event is tribal. Especially when it’s partly on non-tribal land, open to the general public, and inviting thousands of people.

One rulebook—or two?

This isn’t about disrespecting the Canoe Journey. Quite the opposite: it’s a reminder of how important cultural events are to many different groups in Clallam County.

If tribal events are rightly given flexibility and informal coordination, then why aren’t local nonprofits, veterans groups, churches, or ethnic heritage festivals offered the same? Why are they expected to pay thousands, navigate months of paperwork, and go through public hearings?

Clallam County should be asking itself some hard questions:

Can cultural events get a streamlined process?

Should permit fees be waived or reduced for nonprofit or heritage-focused gatherings?

Are we treating all cultures—and all community celebrations—equitably?

Because right now, it looks like there are two systems: one for sovereign tribes, and another for everyone else.

Last Equitable Wednesday, readers were asked if they feel students are being divided by race or identity in the name of “equity.” Of 189 votes:

81% said, “Yes, it creates resentment”

5% said, “No, it fosters understanding”

13% said, “It depends how it’s taught”

1% didn’t know