In Clallam County, justice, taxation, and opportunity increasingly depend on who you are—not what’s fair. See how violent crimes go unpunished, how tax dollars and gas prices are manipulated to benefit political insiders and tribal enterprises, and how local media spins the narrative to keep you distracted. From downtown assaults to multi-million-dollar gas station windfalls, this roundup asks the uncomfortable question: Is our county still working for the people who live in it—or just for those who know how to play the system?

A tale of two deaths

Last month, an elderly straight white man was brutally assaulted in downtown Sequim in broad daylight. The suspect? A person of color with a history of arrests, drug use, and suspected human trafficking. Despite the man’s death, the suspect was exonerated and released. Local media coverage was minimal—barely a blip.

Now, compare that to this week’s headline: the woman long suspected in the death of Native woodcarver George Cecil David was extradited and charged with second-degree murder. Her bail: one million dollars. The Peninsula Daily News highlighted how a culturally informed task force, working with tribal and cross-border groups, helped finally move the case forward.

Justice served? Maybe. But why does one murder trigger a task force and community healing, while another vanishes from public consciousness? Have we reached the point where some lives matter more than others, and identity determines whether your story is told?

If you believe that, 60 years after the Civil Rights Movement, dividing our community into different racial groups is beneficial, take a look at CC Watchdog comments:

Clams for the few

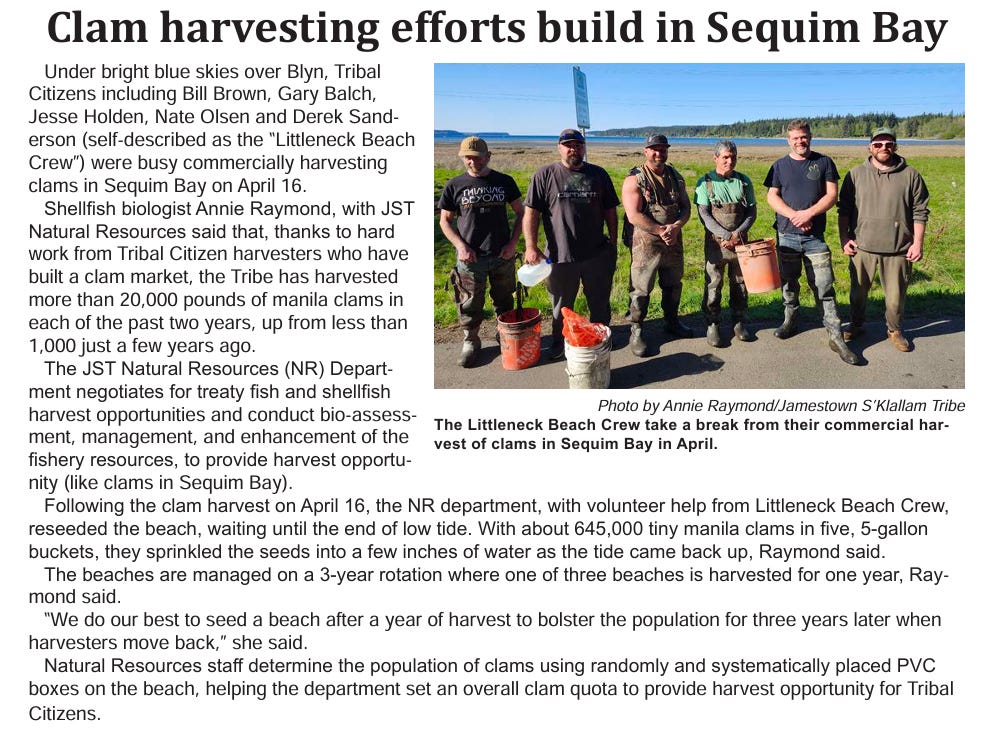

The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s latest newsletter touts a stunning statistic: over 20,000 pounds of manila clams are harvested annually—up from less than 1,000 just a few years ago. That’s nearly 100 pounds of clams per local tribal member. The Tribe’s Natural Resources Department negotiates harvests under treaty rights and coordinates the bounty of Sequim Bay.

In a state that bans non-tribal harvests in many areas and clamps down on rural well use to “protect aquifers,” there’s something fishy about who gets to reap nature’s rewards—and who gets regulated into submission.

RECOMPETE delivers job growth (sort of)

Commissioner Mike French’s much-publicized RECOMPETE program is bringing $35 million to the Olympic Peninsula to help working-age adults get jobs. So what’s the first job created?

A “Recompete Plan Coordinator” paying $100,000 to $122,000—about twice Clallam County’s median household income.

French sees it as an opportunity to train and hire tribal grant writers. Finally, those signs saying “Grant Writer Needed” in business windows might come down.

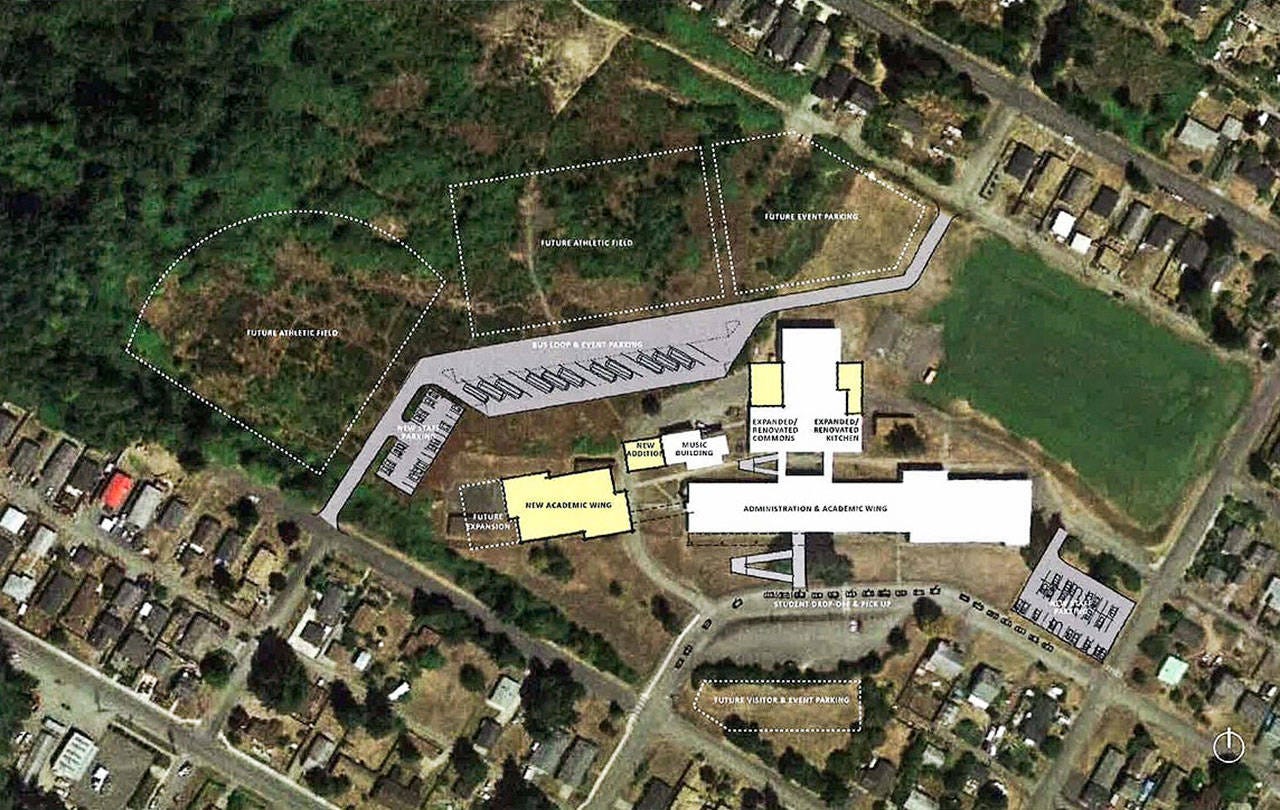

Who’s in charge of the school name?

Stevens Middle School will be renamed when the new school is built in 2027. The leading contender? Hurricane Ridge Middle School—selected in part because it’s “sacred to local tribes.” The committee was composed of staff, students, tribal representatives, and community members. Also in the running: Riverstone, Elwha River, and Port Angeles Middle School.

Local history? Broad community consensus? That’s secondary. What matters is symbolic tribal reverence.

Debunking the environmental myth

An old 5-minute video from John Stossel (yes, that 20/20 guy) challenges a long-held narrative: that Native Americans were peaceful, environmentally harmonious stewards of the land.

Turns out, they took slaves, set massive forest fires, and transformed landscapes—just like European settlers. As Stossel explains, the myth persists thanks to Disney and anti-littering PSAs.

Here at home, modern tribal business empires are building gas stations, watering and fertilizing a 122-acre golf course, commercial farming non-native shellfish species in a wildlife refuge, and pushing for net pen fish farming, but we are assured our tribal neighbors are the best environmental stewards around.

Giving back... tax-free

Tickets are now on sale for a Habitat for Humanity fundraiser—held at the Jamestown Tribe’s golf course. It’s a noble cause, made possible in part by Opportunity Funds from a sales tax... a tax the Tribe doesn’t pay at its businesses and can often waive entirely.

To their credit, the Tribe did donate $50,000 to Habitat and helped hire the nation’s first Native American Housing Liaison. But that no-bid contract for the Carlsborg project? It raises eyebrows. If this is “giving back,” it seems the giving is optional—and the community always pays.

Pronouns and public office

When the Peninsula Daily News reported on Port Angeles City Councilmember Brendan Meyer’s resignation, the story said:

“I thought it was going to be easier than it was,” Meyer said of the conversations they’d been having with themselves over the past two or three months.

Dealing with a serious health challenge — they will only say it isn’t cancer — and the stress of their responsibilities serving on the council finally reached a point where Meyer had to consider what was in the best interest of themselves and family members.

It was only after numerous talks with their wife, Hana, and daughter, Kaydnthat Meyer felt ready to make an announcement they dreaded.

But once Meyer did, at the council meeting Tuesday night, they felt relieved. If anything, they were concerned about disappointing other people.

“I learned a lot and we did a lot of good things that I’m proud of,” they said.

Meyer intends to stay in Port Angeles, where his [a PDN oopsie?] father now lives. However, they intend to step back from public life for a while.

“I’m going to spend time with my family and focus on things that are close to home right now,” they said.

Meyer is still not entirely comfortable with their decision not to serve out the rest of their term, even though they realize it was the right one.

“It’s been a really good ride,” they said.

Wait—They are stepping down?

The only “they” resigning is one person. If news is supposed to be simple, this pronoun acrobatics turns a resignation story into a political performance.

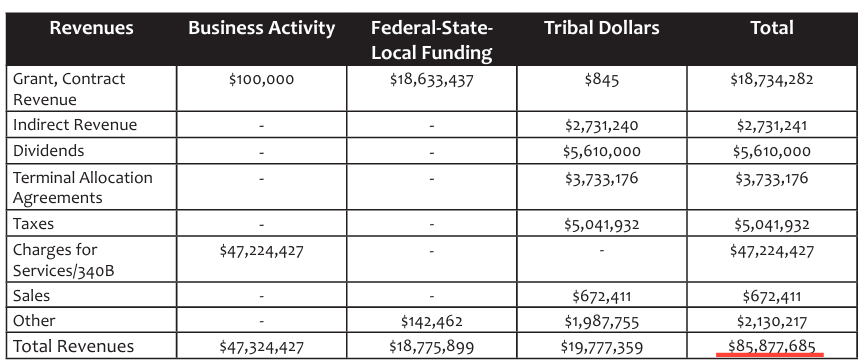

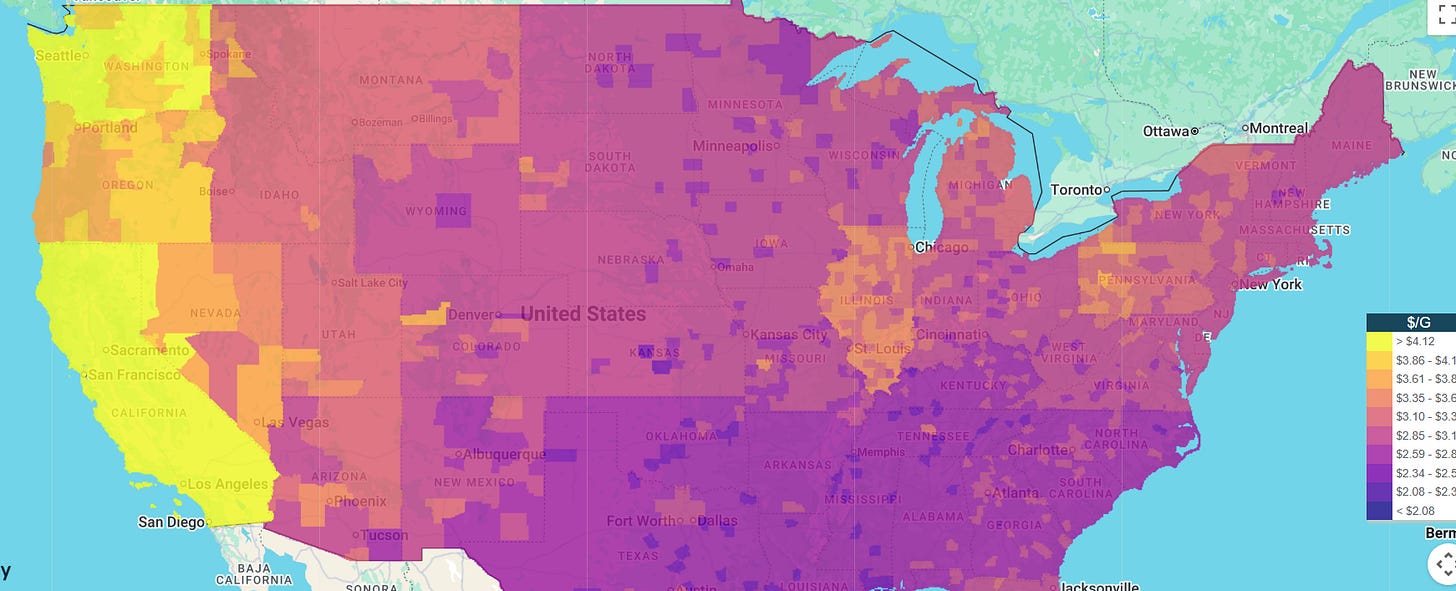

$86 million in revenue—but who benefits?

The Jamestown Tribe reported $85,877,685 in revenue last year—despite having just over 500 members.

But only:

$286,325 went to housing

$589,371 to member services

$13,007,717 to “other uses,” including land and business acquisitions

What percentage of the Tribe’s income reaches its people? And what percentage builds an empire?

The numbers suggest a growing gap between image and impact—between community and corporate expansion.

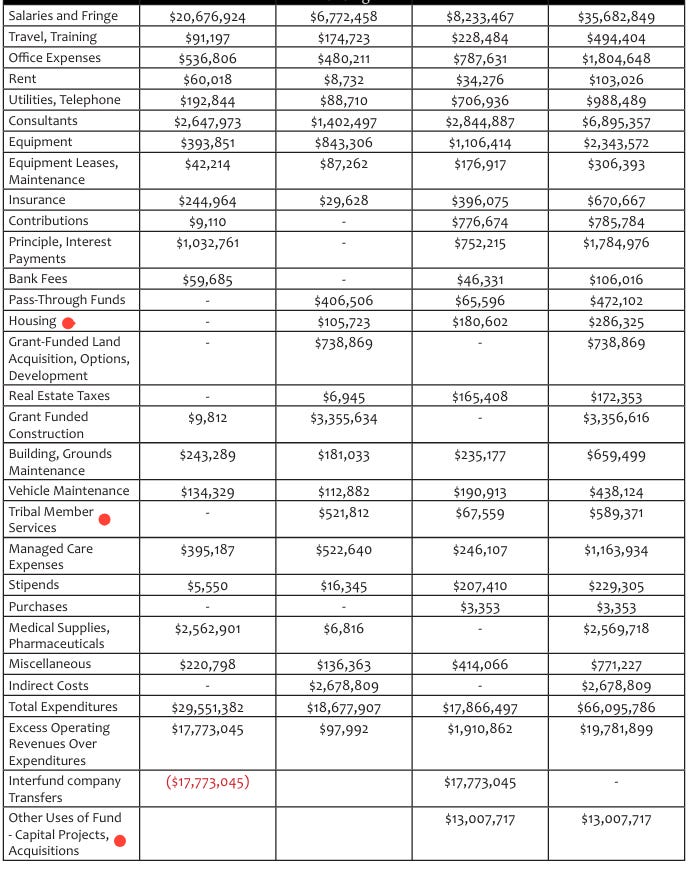

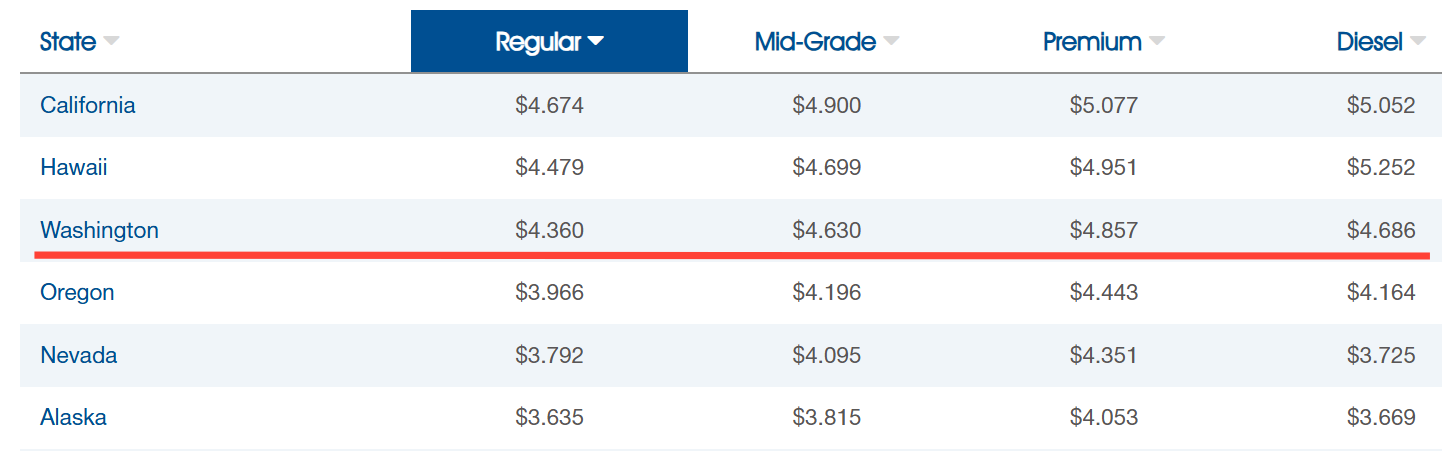

Gas pain, tribal gain

Washington State already ranks in the top three for highest gas prices in the nation, thanks in part to the Climate Commitment Act—lobbied for locally by Clallam County Commissioner Mark Ozias. That legislation funnels millions into “climate justice” grants, many of which go to his top campaign donor, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe.

And now it’s about to get worse.

Starting July 1, the state gas tax rises by another 6 cents, bringing the total to 55.4 cents per gallon. But not every station is hit the same way. Tribal gas stations, like the Jamestown’s Longhouse Market and the Lower Elwha Food and Fuel, keep 75% of that gas tax. What’s a 6-cent cost to you is a 4.5-cent revenue boost for them.

At a high-volume gas station selling around 400,000 gallons per month, that’s $18,000 in additional monthly profit—just from the tax increase. Over the course of a year, the total gas tax revenue could amount to more than $2.6 million compared to their non-tribal competitors, who are unable to keep any of that tax.

No wonder the Jamestown Tribe is planning a truck stop at Diamond Point.

And here’s the kicker: the amount these tribal stations collect—and how it’s spent—is not audited by the state. Instead, it's audited by a third party, and considered “personal information.” That means you can’t see it. No public records. No transparency.

Meanwhile, families scraping by will feel the full burden at the pump, as tribal entities profit and our highways crumble, thanks to billions earmarked for culvert replacement under mandates driven by tribal treaty litigation.

The system works—just not for you.

When protests return to the Peninsula

With protests erupting across the West Coast and demonstrations scheduled locally this weekend, the tension that spilled into our rural towns during the summer of 2020 seems to be creeping back in.

Let’s not forget: some people in our own community, including Clallam County Commissioner Mike French, have gone on record defending riot-based tactics:

“…some property destruction is fine when oppressed people riot… property destruction is not only fine, it’s usually the only way we’ve ever seen actual change happen…”

No, it’s not.

Birmingham’s bus boycott brought the city’s transit system to its knees—not by breaking windows, but by staying home. A massive AIDS quilt spread across the National Mall put a human face on a crisis and changed policy. And Towne Road was opened not by smashing signs, but by writing letters and showing up at commissioner meetings.

Stay safe, Clallam County. Remember that change doesn’t require destruction.