What started as a routine road realignment turned into a case study in government failure, special interest influence, and public betrayal. Clallam County’s Towne Road project—overshadowed by mismanagement, tribal pressure, vanishing transparency, and political favoritism—burned through nearly $1.5 million in avoidable costs, ignored public input, and left taxpayers footing the bill for a private driveway, empty walking paths, and costly environmental overreach. This is the story the official report didn’t tell—and the video every taxpayer needs to see.

For many in Clallam County, the realignment of a 0.8-mile segment of Towne Road was never just about infrastructure. It became a symbol of what happens when public policy is ceded to nongovernmental organizations, special interests, and a sovereign nation. The project exposed the county’s struggles to manage complex partnerships, especially when errors occur and one party claims sovereign immunity, leaving taxpayers to pick up the pieces. Towne Road ultimately galvanized the public to scrutinize local government, revealing a culture of hidden agendas, closed-door meetings, and questionable priorities.

The elusive budget and a narrative instead

After a year and a half of requests for a straightforward budget—a simple accounting money in, money out—the county finally responded. But instead of transparency, residents received a 29-page narrative, not an accounting. The report, presented at Monday’s Board of Commissioners work session, was less a reckoning and more a self-congratulatory exercise. The County Administrator’s remarks were filled with platitudes: “Expect to encounter bumps in the road… Outreach and education is ongoing. People will always have questions! Keep the faith.”

In short, the commissioners got a pass, and the administrator received a glowing performance review—an apparent conflict of interest, as the report essentially evaluated the management of his own bosses.

What caused the report to feature such high praise for the commissioners? That answer may have appeared in the following agenda item: The annual review of the County Administrator, as given by the Board of Commissioners who hire, fire, and determine compensation of the County Administrator.

Grants, delays, and the breach

The county’s narrative traces the project back to 2017, detailing over $14 million in grants, with nearly $17 million in construction grants. But the heart of the controversy lies in the spring of 2022, when the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe breached the upper portion of the original 1964 Corps levee before the county completed its Phase 2 work. This move, which the county’s own report glosses over, nearly resulted in a mass casualty event in Dungeness.

“News helicopters would circle the devastation and speculate on the number of dead. The County, Tribe, and the Corps would be embroiled in wrongful death suits for years or decades.” — Jamestown Tribe’s Habitat Program Manager Randy Johnson (not to be confused with the County Commissioner by the same name.)

The rationale remains unclear—was it miscommunication, a push to meet obligations, or a breakdown in oversight? The county’s own staff admit any conclusion is speculation.

What is clear: the Tribe, a sovereign nation, has refused to communicate about the breach, even as the county continues to partner with them on future projects—like constructing an above-ground reservoir atop earthquake fault lines.

Ignored warnings and protocol violations

Documents reveal that the Tribe’s own bid instructions prohibited removing the old dike until the county completed the new levee. Yet, the breach occurred a year before the county’s work was finished. When pressed, the Tribe’s natural resources director, Hansi Hals, called the action “usual and acceptable,” despite evidence to the contrary.

Internal emails show county staff recognized the risks. Habitat biologist Cathy Lear warned that the Corps levee should remain until all flood protection was in place, noting that removing it prematurely endangered both the community and the restoration project. The Tribe’s aggressive timeline, coupled with the county’s delays due to permitting and funding, created a dangerous disconnect.

The temporary dike debate

Administrator Mielke’s report fails to mention that the county scrambled for solutions, and a temporary dike west of the Creamery was proposed—an option that would save taxpayer money and keep Towne Road open. The Tribe, however, opposed this, citing treaty rights and equity concerns. The only flood protection option that would benefit residents was dismissed on grounds of justice and environmental obligations.

“The Tribe has been advocating for the realignment of the dike for more than 20 yrs because their treaty rights have been impacted. Rebuilding a harmful structure on the Tribe’s property reveals a deep equity/ justice issue to me personally.” — Jamestown Tribes Natural Resources Director, Hansi Hals, recommending that the County pursue a more expensive option to address the breach

Emails between county officials reveal a project hampered by distance, turnover, and a lack of clear authority. The Director of Community Development was often out of state, and the county engineer retired suddenly. Decisions were made via text and Zoom, with critical updates lost in translation.

The cost of premature action

Lear estimated that the Tribe’s premature dike removal cost the county tens of thousands in consultant fees alone, with total expenses likely far higher.

The Tribe’s untimely action is also expensive. The County’s consultants’ time alone to date will cost the County ~$30,000 for meetings, modeling, analysis, and design options generated solely to address the Tribe’s premature removal of the Corps levee. Total cost for consultants may be ~ $50,000 when all is said and done.

We continue to talk with Tribal staff, but as the below email indicates the Tribe intends to continue its removal of the levee with no plan to address issues that the removal creates. Such an approach puts at risk years of effort to bring this project to fruition.

More troubling, modeling suggested that without the Corps levee, the floodplain could inundate at flows as low as 1,300 cubic feet per second—putting homes, roads, and years of restoration work at risk.

Lear wrote:

In my view, the Tribe’s actions in removing any portion of the Corps levee were/are premature, costly, and do not reflect conditions on the ground. Removing portions of the Corps levee imperils both the downstream community and the floodplain restoration project itself. Were the river to flow into the rest of the floodplain, with no exit route, it has the potential to strand the Corps levee, disrupt the surface of Towne Road, flow into the west tributary and then into Meadowbrook Creek, and/or overtop the Corps levee and return to the river. Stranding the levee creates a morass of habitat, flood hazard, permitting, and construction cost impacts. River water flowing into the west tributary and Meadowbrook Creek will likely produce downstream flood impacts along with flooding on Towne Road near the Schoolhouse. River water overtopping the levee and re-entering the river could affect Schoolhouse Bridge.

Lessons unlearned

Here’s what the report left out:

Land acquisition? The report states that $575,000 was spent on land acquisition, but a Peninsula Daily News article indicates that two properties the county purchased were valued at $525,000 and $500,000.

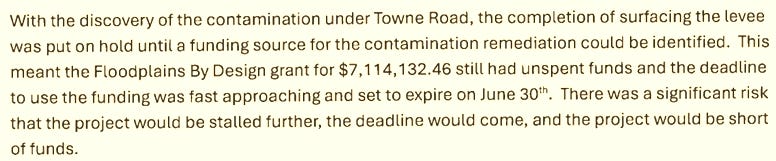

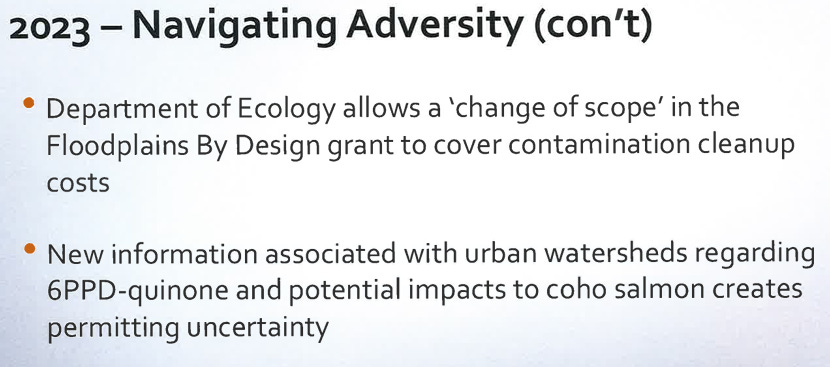

Soil contamination cost misrepresented: The report says that by Spring 2023, there was no identified source of funding for cleanup. But months earlier, in February 2023, the Department of Ecology agreed to cover the full $1.1 million cost.

History was ignored: In 2015, the County polled the public and found 83% wanted Towne Road open.

The report never addresses the issues associated with breaching the dike early. In an email, Administrator Mielke stated that the response to the breaching of the levee was estimated to cost between $10.5 million and $13.8 million, so the county decided to oversee the construction in-house. How much did that cost the county?

“Declaration of Emergency was made in 2022 as a result of the breaching of the levee. In response to that Declaration, the County developed an “Engineer’s Estimate” of what was believed it would cost to respond to that breach. This estimate was $10,581,472.90. The work was put out for bid, and the ‘lowest qualified’ bid came in at $13,817,360.82 – which was ultimately rejected due to it being $3,235,887.92 HIGHER than the Engineer’s Estimate. The County then decided to oversee the construction of relocating the levee and Towne Road in-house (utilizing both County staff and overseeing other engineers/contractors).”

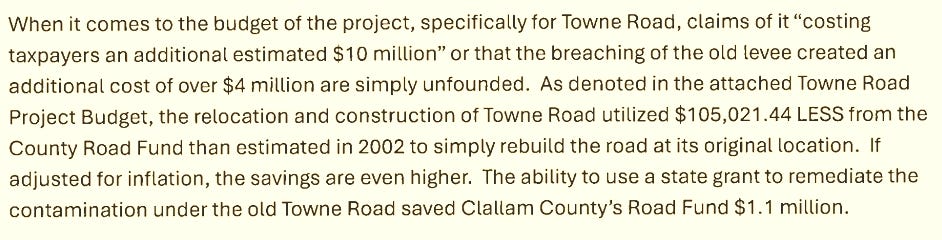

The report says claims that “the breaching of the old levee created an additional cost of over $4 million are simply unfounded.”

However, this Change Order Description from August 2022 states: “This change order results in a net change in total contract cost of $4,162,212.50.”

Public input was weaponized: The County paused reconstruction not because of the soil remediation, but after receiving petitions—98 people wanted it closed, while 122 wanted it open. Yet the will of the majority was ignored.

$500,000 in hush money?: On August 1, 2022, the County’s emergency declaration blamed the Tribe for the breach. The next day, the Tribe offered $500,000 if the language could be changed. It was. The Army Corps was blamed instead.

Emergency responders couldn’t reach a home in time due to the closure: A family was left homeless. No mention of that in the report.

Electric gates for a campaign donor?: Commissioner Ozias instructed a consultant, paid at $210/hr, to design and price three automatic taxpayer-funded gates to turn the public road into a private driveway. How much did that cost taxpayers?

Environmental rules applied inconsistently: The Tribe demanded an expensive 6PPD-quinone filtration system to capture tire particulates—the first of its kind in Washington for a county road. The controversy arose in early-2024, not 2023 as the report claims.

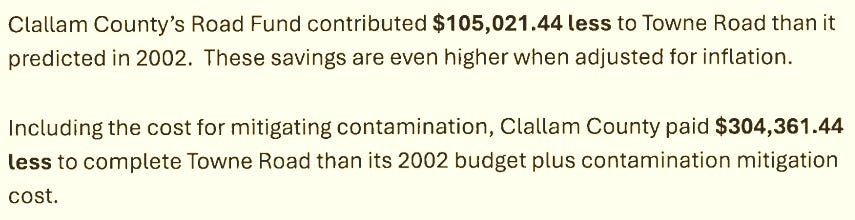

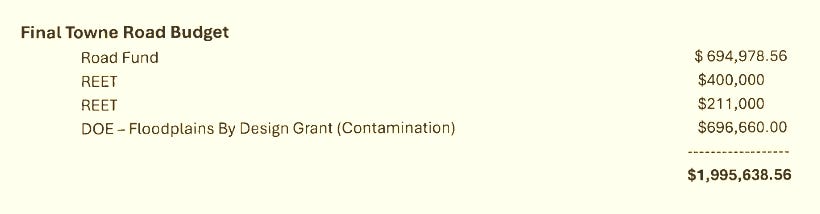

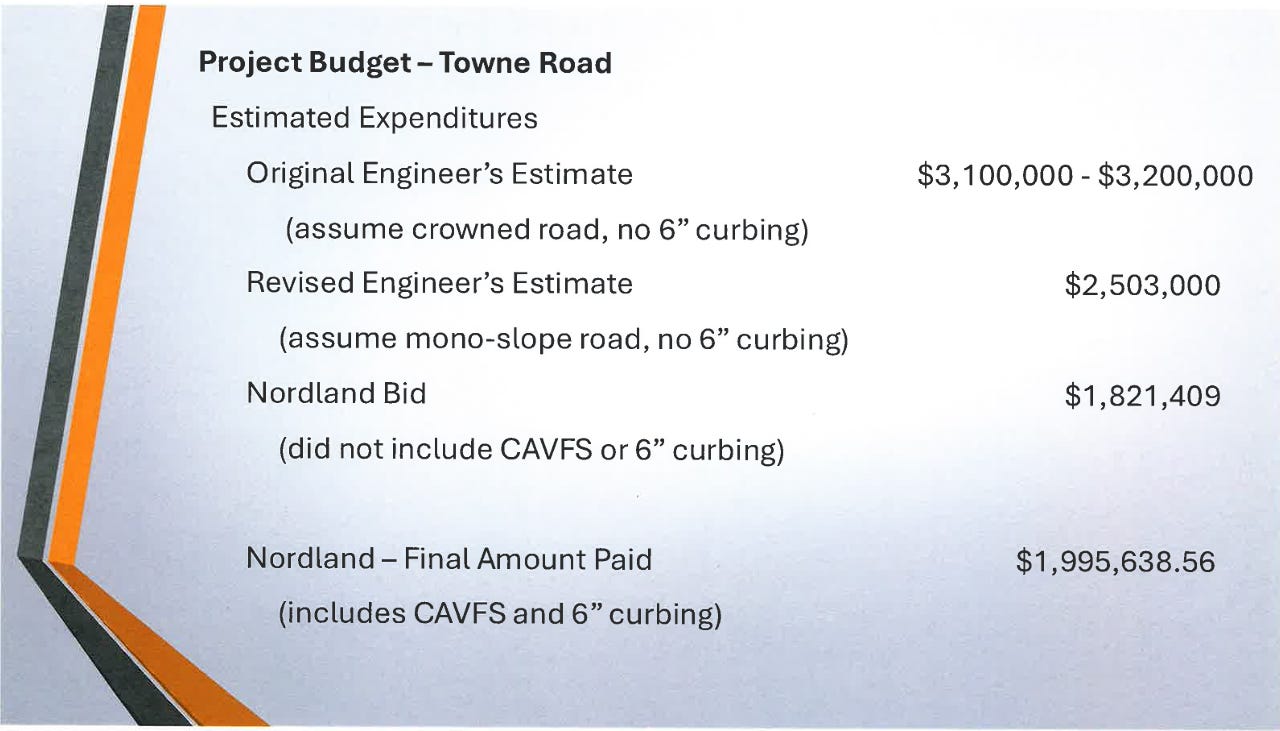

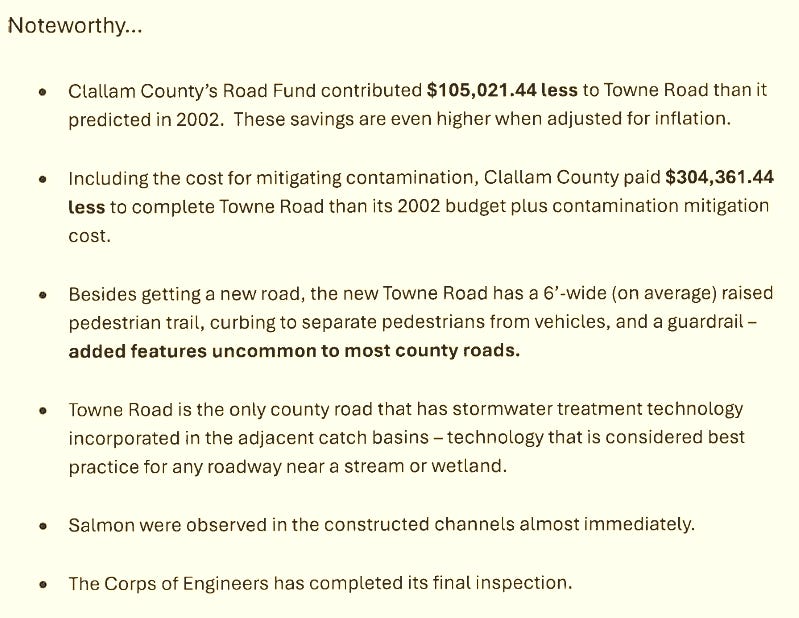

The County bragged about saving $105,021 and $304,361 compared to a 2002 estimate—on a $22.5 million project. Their definition of success is comparing the end result to an estimate over two decades old.

In February 2023, when the commissioners decided to halt the project and allow a grant to expire, the county engineer warned them that the county would be responsible for covering the costs. The $694,978.56 from the Road Fund and $611,000 from the two REET funds were unnecessary county expenditures.

The Tribe’s demand for a filtration system, combined with the curb insisted upon by Commissioner Ozias, increased the price by $174,229.56.

When adding the county’s use of the Road Fund, the two REET Funds, and the additional cost of the curb and filtration system, Towne Road unnecessarily cost taxpayers $1,480,208.12. What could that money have done to improve 3 Crabs Road? How might it have been used at one of the County’s most dangerous intersections, like Old Olympic Highway and Cays Road?

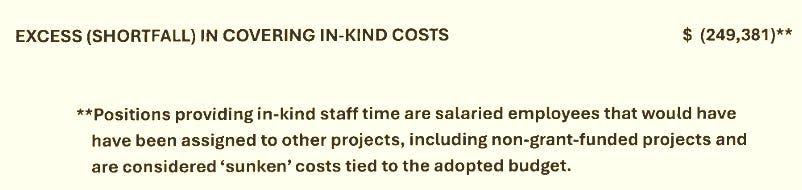

According to the county, the Towne Road project contributed nearly $250,000 to the county’s overall general fund. Why wouldn’t we embark on another road relocation project if, according to the county, we made money?

The Towne Road saga is a cautionary tale about the perils of opaque governance and unbalanced partnerships. When public agencies defer to outside interests without accountability, the community pays the price—in dollars, trust, and safety. As Clallam County moves forward, residents should demand not just transparency, but genuine oversight and a commitment to the public good.

Bonus content: The $1.3 million work session

To understand how just one hour of waffling by Clallam County Commissioners cost taxpayers over $1.3 million, you need to watch this video, starting at 51:50. It’s the February 27, 2023 Board of County Commissioners work session—held six months before the public was told Towne Road might be permanently closed.

This one meeting reveals about 80% of the Towne Road debacle—how special interests influenced public infrastructure, how county leadership bent to private pressure, and how mismanagement and indecision drained the budget.

Here's what you'll see:

57:25 – County Engineer Joe Donisi outlines the funding plan. He explains the county has secured grants for project completion—but warns they’re expiring soon. If not used, the county would have to “reach deep into Roads [fund].” Worst-case scenario: the county would need to dip into Real Estate Excise Tax (REET) funds.

59:30 – The project qualifies for a 0% match: no county money needed. A rare chance to build with 100% outside funds.

1:00:01 – The $1.1 million cost to remove contaminated soil is fully covered by the Department of Ecology.

1:05:00 – Commissioner Ozias raises concerns—not about funding or public need, but about a private driveway for a single landowner.

1:08:45 – Commissioner Ozias floats the idea of trail alternatives. Donisi replies that while there’s not enough room for a trail beside the road, there’s ample space for a standard two-lane road with 4-foot shoulders.

1:13:00 – The county attorney warns: if the terms of the grants aren’t followed, the money could be clawed back.

1:14:00 – DCD employee Cheryl Baumann, speaking against her own department’s position, argues the road shouldn’t be rebuilt.

1:19:45 – Habitat Biologist Cathy Lear reminds the group: the County already agreed to relocate the road in grant documents.

1:20:30 – Donisi stresses again: time is running out to use grant funding. If the county delays, the opportunity is gone.

1:25:45 – Commissioner Ozias claims “well over 200” signatures were received asking for the road to remain closed. The actual number? 98. Meanwhile, 122 people asked for it to be reopened. Still, Commissioner Ozias refers to it as a “groundswell of support” for closure. The private landowner wants a public road turned into their personal driveway. Commissioner Johnson agrees. Commissioner Ozias brings up the landowner’s desires repeatedly.

1:32:50 – Commissioner Ozias says, “I’d rather turn the grant dollars back.” Johnson concurs.

1:33:10 – Commissioner Ozias: “One of the most important pieces is what the private landowner wants for their driveway.”

1:38:25 – A county employee points out that the public process was already honored in 2015, when a supermajority of residents voiced they wanted the road to remain open.

1:44:10 – Commissioner Ozias closes with this: “I’m personally not convinced that we need a road of any kind at all—especially if the Eberles don’t want it.”

Last Sunday, readers were asked if drug supplies should be distributed by private citizens without official oversight. Of 220 votes:

1% said, “Yes”

95% said, “No”

4% said, “Only with strict accountability”