Washington’s annual drought declarations unleash millions in grants—but not for who you think. While rural homeowners face restrictions, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe collects drought funds and keeps its golf course pristine. Meanwhile, science showing that ditch removal harmed aquifers was quietly shelved. The real drought? Accountability.

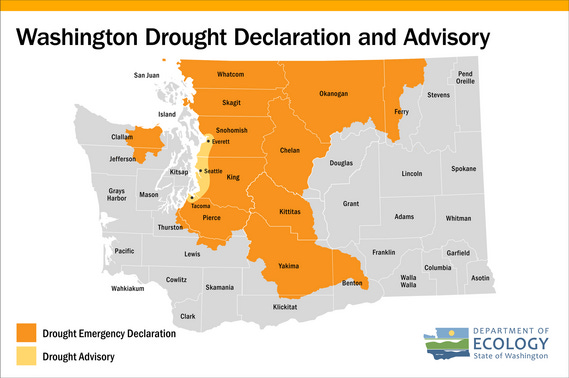

This week, Casey Sixkiller, Director of Washington’s Department of Ecology, announced what’s becoming a rite of Spring in Olympia: another drought declaration.

Counties along the I-5 corridor, the eastern Cascades, and one more conveniently-placed region have been declared officially dry.

But don’t expect this announcement to summon rainclouds or refill aquifers. It doesn’t release water—it releases money.

To the tune of $4.5 million in drought relief grants.

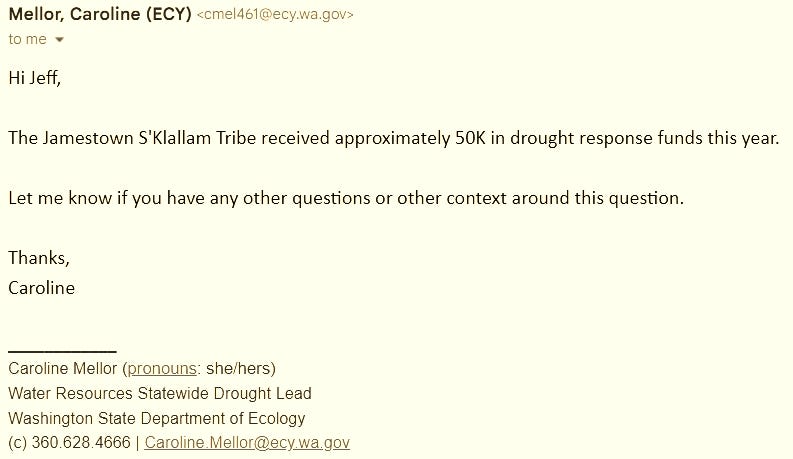

And while the press releases promise “relief to public entities,” what they often deliver is a windfall to political allies and well-connected tribal governments—such as the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, which received about $50,000 in last year’s drought cash.

That’s not just according to watchdogs—it’s from Ecology itself. Water Resources Drought Lead Caroline Mellor confirmed the Tribe's payout in a December 2024 email.

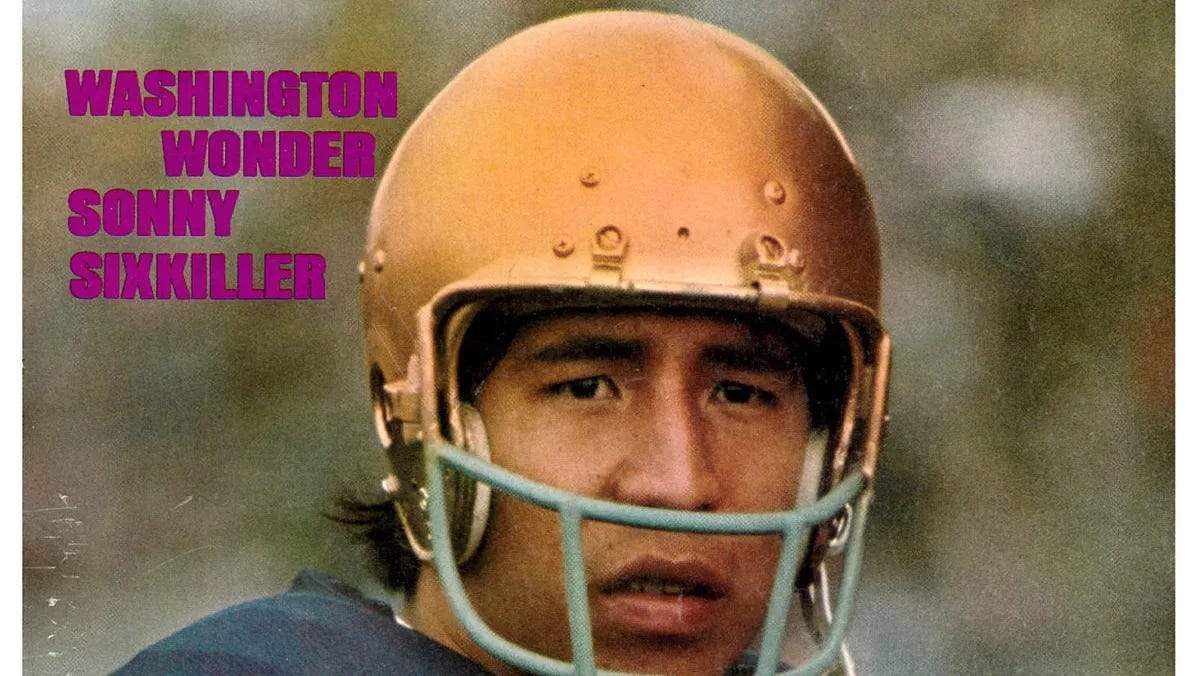

Who is Casey Sixkiller—and why does his name ring a bell?

For those who follow Northwest sports or tribal partnerships, Ecology’s Director Casey Sixkiller’s last name carries weight. His father, Sonny Sixkiller, is a former UW quarterback turned regional celebrity.

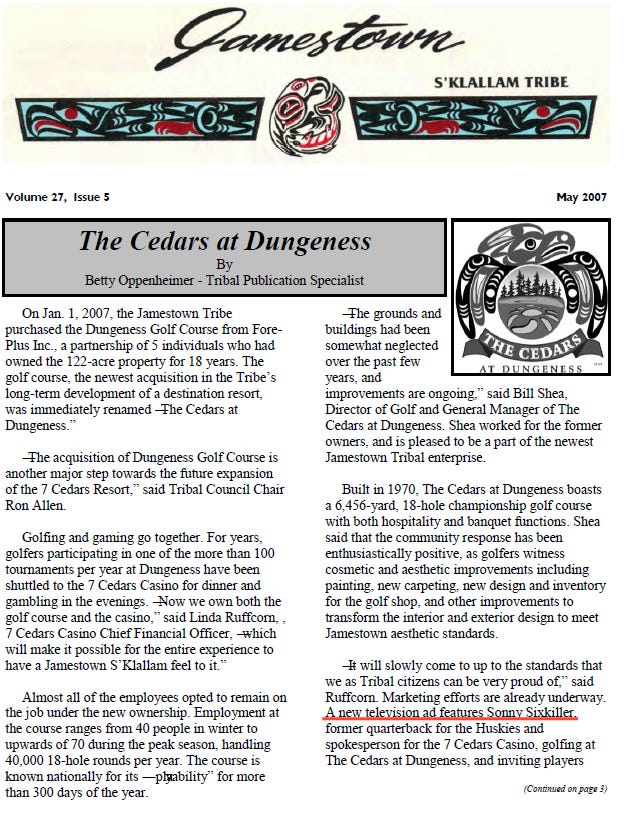

He’s also the co-founder of the Sonny Sixkiller Celebrity Golf Classic, launched in 2011 with—you guessed it—the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. The tournament, held at the Tribe-owned Cedars at Dungeness Golf Course in Sequim, brings together celebrities, athletes, and political players for a round of golf and good press.

Sonny’s role doesn’t end there. He appears in promotional videos for tribal enterprises and is something of a de facto spokesman, pumping up everything from the Tribe’s golf course to its luxury hotel.

Drought dollars, strings attached—and controlled messaging

So, what did last year’s $50,000 drought grant to the Tribe buy? In part, it paid for a four-page Memorandum of Agreement outlining how the grant would be used—chiefly for outreach aimed at one particular audience: you, the person watering your lawn and plants. You, whose well is under constant scrutiny.

Outreach activities were required to include:

At least one PDN article and KONP radio interview

In-person workshops for Water User Association members

A detailed final report to the Tribe outlining deliverables and lessons learned

Because when you fund the message, you get to control the message.

One such public outreach event took place last December at Sequim City Hall. It was billed as a “Water Conservation Forum.” It ran an hour over schedule, offering a clear lesson in Clallam County time management: When government has a message for you, there’s always time. When you have a message for them? Three minutes, max, during scheduled public comment.

Expert-free experts

The first speaker was Ann Soule, longtime League of Women Voters activist and retired hydrologist, who spent 40 minutes walking the audience from the last Ice Age to modern water policy. She even claimed that while irrigators have rights to irrigate, “they didn’t have rights to supply the aquifer with any water.” This, after an announcement that the panelists weren’t experts in water law and would not be weighing in on legalities.

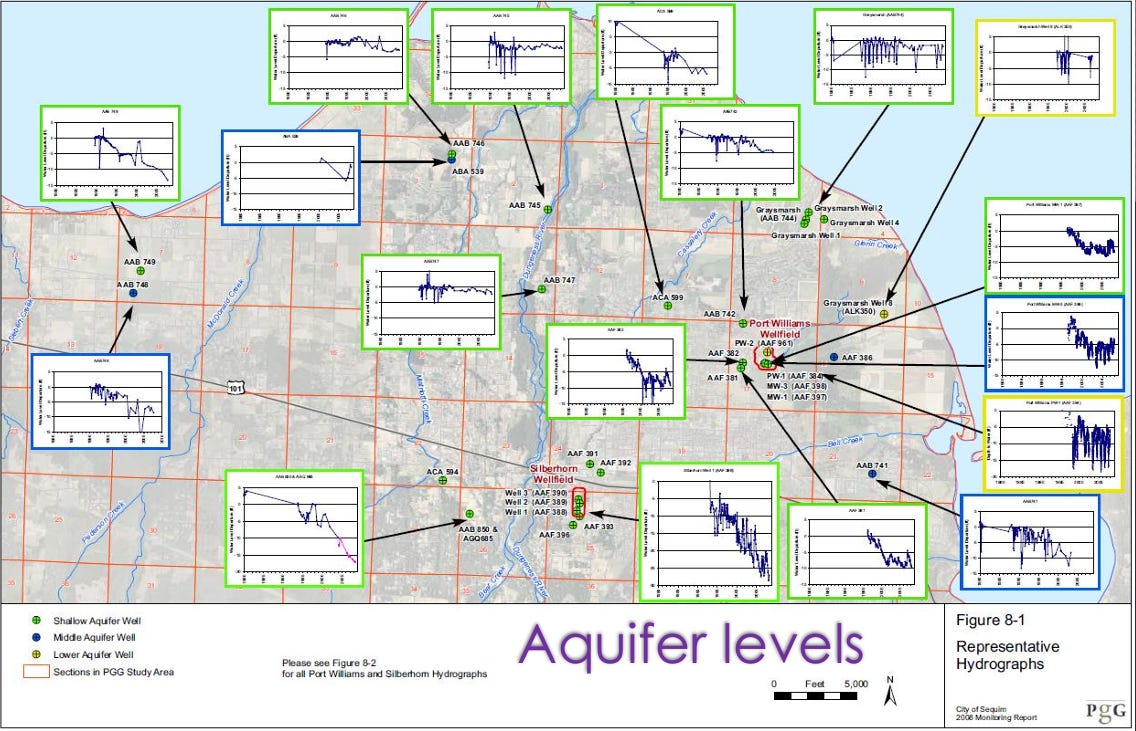

Soule presented a series of hydrographs from the city’s own 2008 Hydrologic Monitoring Report, prepared by Pacific Groundwater Group.

Her conclusion? Open irrigation ditches raised aquifer levels—by “dozens of feet.” The data tracked a clear decline in groundwater after miles of those ditches were replaced with underground pipelines.

Then, the monitoring abruptly stopped.

The hydrologist, half-jokingly, asked the audience if anyone wanted to volunteer to continue it—acknowledging the study had not been updated since 2008.

Maybe the data stopped flowing because the results didn’t fit the narrative.

The evidence suggests ditch removal harmed aquifer recharge. In a county where “follow the science” is the mantra, this science was quietly retired when it became politically inconvenient.

“Sucky” science

Then came Chandra Johnson, GIS and data specialist for the Jamestown Tribe, whose presentation largely focused on tribal history, “time immemorial” messaging, salmon restoration, and climate change. She told the audience that habitat destruction had made many river areas “suck” and that “a lot of places in the lower river, the habitat kinda sucks, and it can be some of the worst habitat in the river.”

After Johnson, the presentation wrapped with suggestions like mowing less, letting your lawn brown, and using a broom instead of a pressure washer.

Oddly missing: any mention of the Tribe’s 18-hole, 122-acre, perfectly manicured golf course—which is green, lush, and mowed even during peak drought conditions. Unlike your backyard, tribal lands are sovereign, and state restrictions don’t apply. The “golf course look” might be bad for groundwater, but not if you’re exempt.

Drought for thee, green grass for me

Meanwhile, the Dungeness Water Rule, heavily influenced by the Jamestown Tribe, maintains that every drop of water drawn from wells “impacts” the Dungeness River, thereby infringing on treaty rights. This interpretation has led to oppressive regulations and mitigation fees for rural residents, while tribal enterprises remain untouched.

So when the Tribe—through Sixkiller’s Department of Ecology—tells the public to let their lawns die and give up car washes, it rings hollow.

The real drought is in accountability

Declaring a drought doesn’t make it rain. What it does is open the floodgates for grant money, bypassing legislative oversight and funneling funds into pet projects and pre-scripted PR campaigns.

As the Clallam County Charter Review Commission floats the idea of a taxpayer-funded “Water Steward,” the public should ask: Will this new position regulate everyone equally—or just pile more rules on rural landowners while exempting tribal developments?

Because if recent history is any guide, drought declarations aren’t about weather.

They’re about money, messaging, and selective enforcement.