From rising property taxes and tribal land exemptions to city bureaucracy blocking business growth, Clallam County residents are seeing firsthand how accountability often falls short. This collection exposes hypocrisy, fiscal mismanagement, and decisions that favor insiders over taxpayers, while highlighting candidates and community voices working to restore common sense and public trust.

Former senator’s irony on property taxes

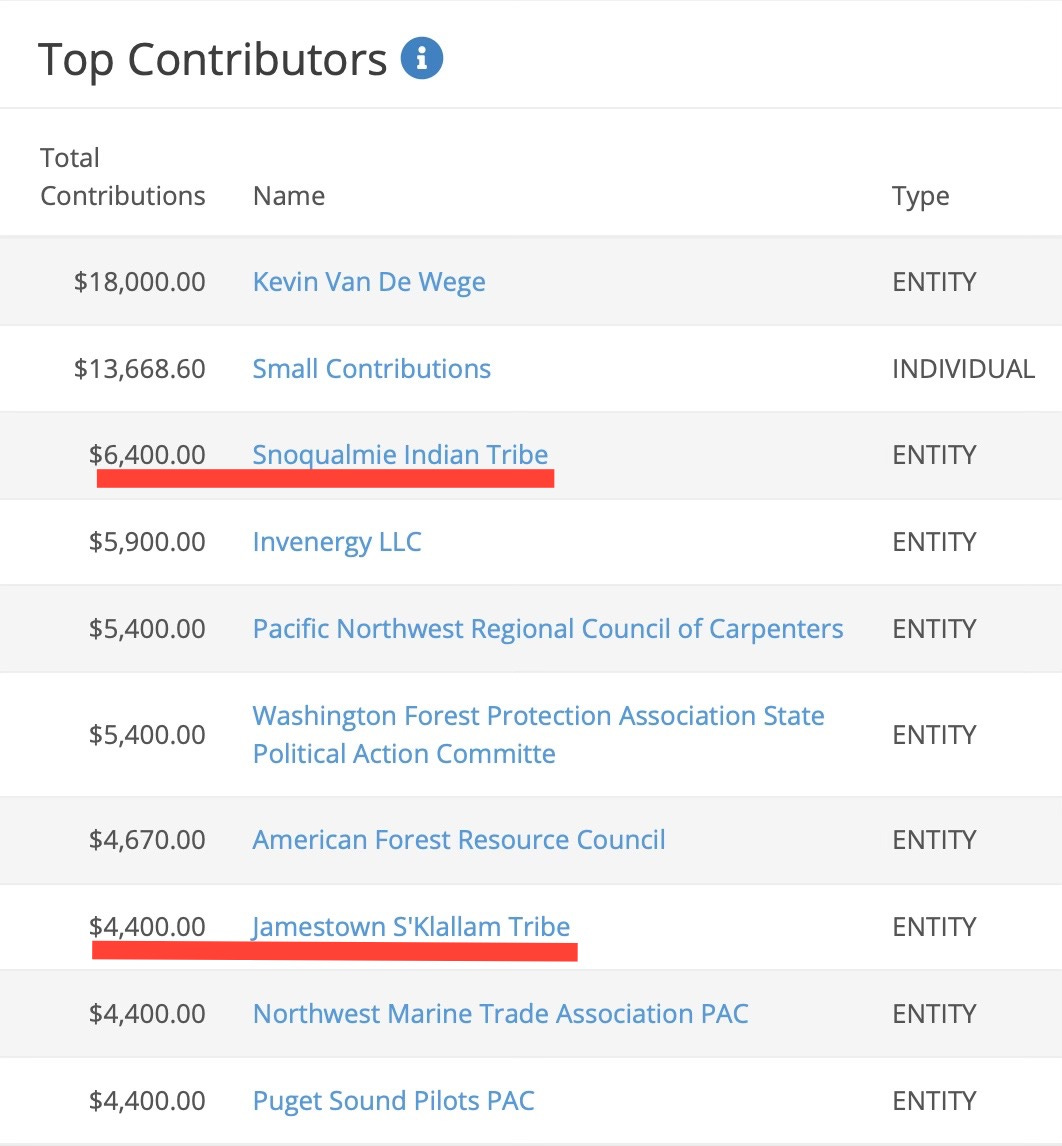

Former state senator and representative Kevin Van de Wege commented on a recent Facebook discussion about rising property taxes, noting that senior citizen exemptions cost far more than tribal trust land exemptions—without providing any numbers.

The irony is striking: Van de Wege is a Captain at Clallam County Fire District 3, a department funded by the very property taxpayers whose bills are increasing.

A recent levy raised that portion of their taxes by 35%, yet tribal land held in trust remains exempt. Meanwhile, the funds saved by these exemptions can be funneled into political campaigns, including Van de Wege’s own.

This situation highlights the ongoing tension between taxpayer-funded services and political interests benefiting from exemptions that shift costs onto the broader public.

Healthcare access failing residents

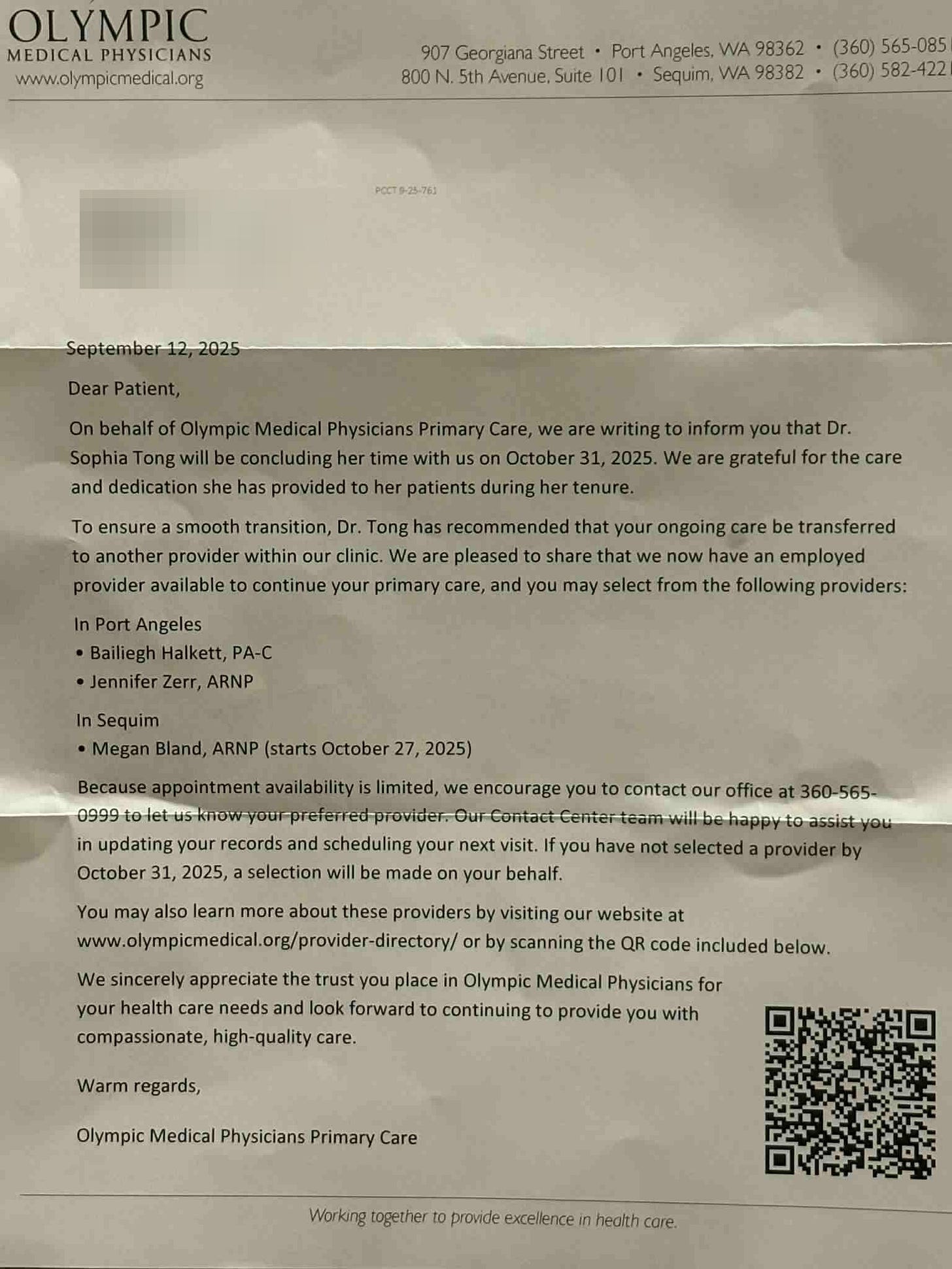

A CC Watchdog subscriber recently shared a troubling experience: after years with the same doctor, they were informed by Olympic Medical Center that they must choose from three non-doctors or have one assigned to them. The patient has several serious conditions, including lung nodules that could develop into cancer, and has been unable to secure a doctor for five years.

“Well. I was served notice from OMC that I will no longer have a doctor and must pick from these 3 non doctors. Or they will pick one for me. I have been denied a doctor for 5 years since Dr oaks quit and went to the native clinic in Sequim. And the Native Clinic refused to let me join their clinic and Continue seeing my doctor. I am disabled and have several conditions that need care including lung noduals that may turn to cancer. I give up. I have been with this doctors clinic since birth 64 years ago. I have decided I will not continue to seek any treatments and let Gods will be what it is. I’m pretty tired of the fight for my health.”

This points to a larger issue: as the hospital struggles financially, experienced staff are leaving, and the community bears the fallout. Meanwhile, residents face restricted access to fully licensed physicians—MDs or DOs with independent practice authority—replaced by physician assistants or nurse practitioners, who, while highly skilled, do not always provide the same scope of independent care.

The situation underscores the human cost of mismanagement and financial instability in local healthcare.

Dungeness River disaster: A tie to Suggs

In spring 2022, the Jamestown Tribe breached the Dungeness River dike ahead of schedule, threatening the community with a potential mass casualty event. County staff identified a $200,000 solution to secure flood protection, but the Tribe refused and demanded a $15 million bond instead.

Emails from county staff show tense negotiations and a lack of resolution, with the resulting solution far exceeding the county’s estimate. LaTrisha Suggs, then a Tribal restoration planner and current Port Angeles City Council candidate, was involved in pushing for this expensive solution.

In an email, county staffer Cathy Lear, who was managing the project, wrote:

It turned out to be a long session. BOCC ultimately rejected the bid but obviously

a hard decision, bound up with the need to provide flood protection this year.

Afterwards, Joe, Randy, and I talked for hours about possible ways forward.

Hansi, LaTrisha, and Cheryl joined in at different times. We finished up around 4.

No real answers yet about how to move the project forward, how to address need

for emergency levee, and whether those two are intertwined. The good news is we

are all still talking.

The case raises questions about priorities: is Suggs advocating for the City, her Tribal interests, or her political ambitions? County taxpayers ended up shouldering a cost 75 times higher than necessary, with a project that closed a road and disrupted the community for two years.

A better option for Port Angeles: James Taylor

James Taylor highlights a recent ruling in the Platypus Marine v. City of Port Angeles case. Although the legal decision favored Platypus, the drawn-out conflict cost millions in lost revenue and delayed dozens of good-paying jobs.

Taylor emphasizes a recurring problem: a city bureaucracy more focused on control than growth, creating obstacles for local businesses rather than supporting them. The ruling shows how defensive, territorial policies undermine economic opportunity and burden taxpayers.

Taylor offers an alternative to the status quo, advocating for policies that encourage investment, job creation, and cooperation between government and business. For residents seeking common-sense governance, Taylor represents a clear contrast to entrenched city practices.

Read his article here.

Transparency questions: Marolee Smith Dvorak

Port Angeles Council candidate Marolee Smith Dvorak raised concerns about the sale of surplus city equipment, asking how proceeds were applied toward new purchases. Responses from city officials were evasive, leaving the public without clarity on taxpayer funds.

Dvorak’s inquiry highlights a pattern of limited transparency in city operations. Simple questions about public money are met with blank stares or delays, revealing how easily accountability can be overlooked. She represents a push for clearer oversight and responsible stewardship of local resources.

Read her full article here.

Meet the candidates: Taylor & Smith-Dvorak

Marolee Smith Dvorak and James Taylor invite the community to a meet-and-greet at Barhop Brewing in Port Angeles, Sunday, October 12, from noon to 1:30 p.m.

This is an opportunity to meet two candidates seeking to bring fresh perspectives to the City Council. Unlike typical campaign events, they are not soliciting donations but aiming to build direct connections with voters, discuss priorities, and answer questions about their plans for the city. Residents are encouraged to join, learn, and engage in person.

Levy lid lift: Questionable priorities

The latest newsletter from Clallam Democrats urges residents to support Proposition 1, the proposed county levy lid lift, and features a statement from County Commissioner Mark Ozias:

“Please support the modest Clallam County general fund levy lid lift this November so we can maintain service across all departments, from Sheriff’s deputies to Public Health to Community Development to elections. The county has worked very hard to cut costs and build efficiencies, but without additional support from you, we will be forced to consider additional painful cuts.”

While Commissioner Ozias frames the levy as necessary to maintain essential services, critics note ongoing spending on programs that raise questions about priorities. These include a county poet laureate, over $12,000 in annual pizza for homeless programs, and private security for personal acquaintances and political allies.

Environmental stewardship: Beyond tribal narratives

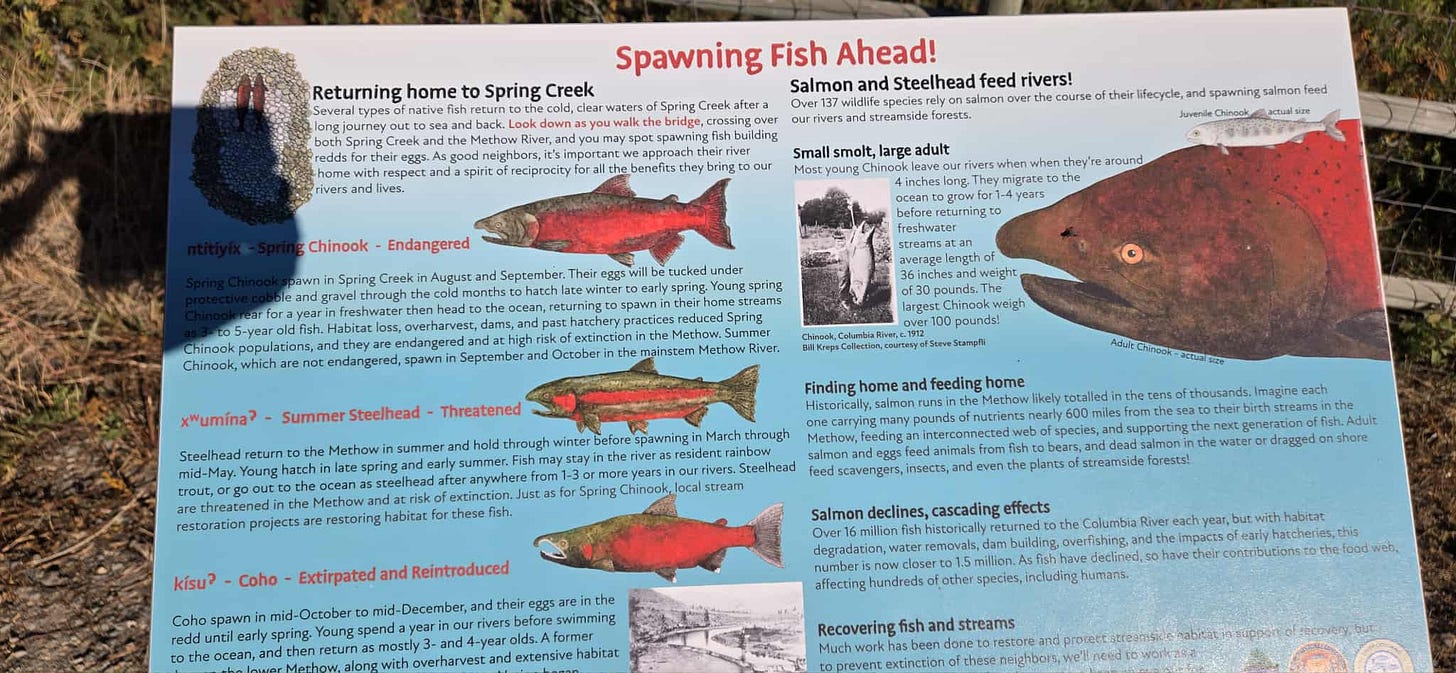

A subscriber visiting a festival in Issaquah…

and also hiking in Winthrop…

noticed something missing from salmon-centric signage and activities — there was no mention of tribes. On the Olympic Peninsula, local narratives often present tribes as the primary environmental stewards who are bestowed with an ancient ecological knowledge tied to cultural and spiritual practices.

This observation challenges the assumption that cultural heritage alone ensures effective conservation. Salmon restoration and environmental protection rely on science, data, and professional expertise as much as tradition, highlighting the importance of merit-based approaches alongside cultural acknowledgment.

Jefferson Land Trust and tribal acknowledgments

In Jefferson County, diners at the Inn at Port Ludlow are automatically opted into a 1% contribution for land preservation through Jefferson Land Trust.

The organization acknowledges the land’s Indigenous history and the displacement caused by colonization.

Yet historical nuance is complex: the Klallam Tribe exterminated the Chemakum Tribe, raising questions about historical accountability and current narratives. While the trust emphasizes reconciliation and collaboration, the ongoing focus on tribal lineage and guilt invites debate about how history should inform present-day policy and public expectations.

Indigenous Peoples’ Day: Virtue signaling or accountability?

At Tuesday’s meeting, Commissioner Mark Ozias delivered a proclamation recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day, citing systemic racism and historical impacts and calling for greater understanding and reconciliation.

But as his words echoed through the chambers, one detail stood out: for the second year in a row, no tribal representatives were present to receive it. No one from the tribes the proclamation was intended to honor—only Commissioners Ozias and French applauding themselves (Commissioner Johnson was absent).

To frame historical injustice in local context: on September 21, 1868, a tragic event now known as the Dungeness Massacre took place, when Jamestown warriors attacked a group of the Tsimshian tribe camping on the New Dungeness Spit, killing 17, including women and children. It remains one of the region’s most violent intertribal conflicts — a reminder that tribal histories are complex, interwoven, and not always aligned in narratives of unity and victimhood.

Every culture has a history of violence, conquest, and wrongdoing—none are exempt. Yet county leaders single out selective narratives to appear virtuous, turning complex history into political theater. These proclamations cost nothing, achieve nothing, and serve mainly to signal morality and court donations rather than foster genuine understanding.

Historical reconciliation: The Tsimshian question

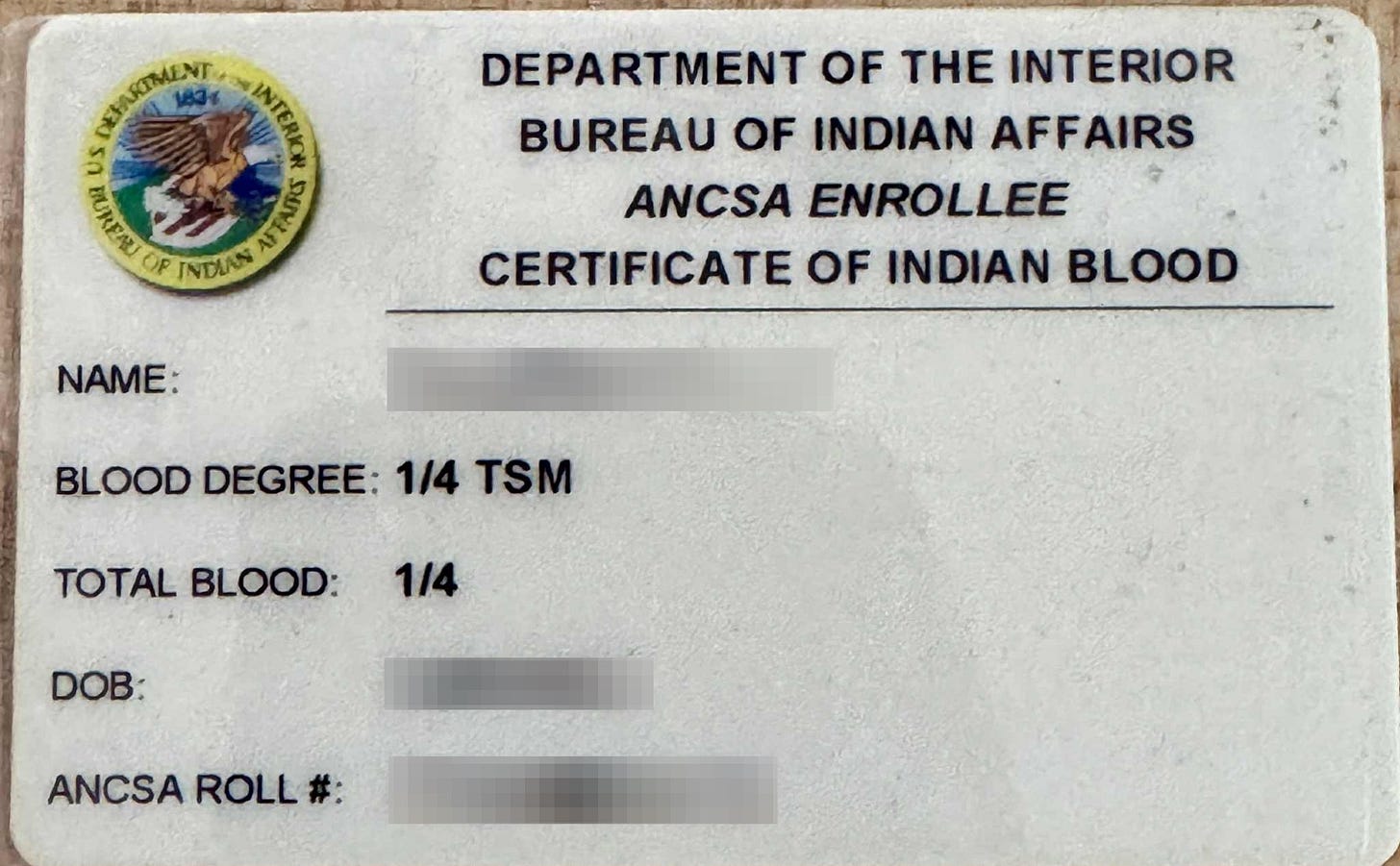

A Clallam County resident, who is one-quarter Tsimshian (TSM), recently shared his Bureau of Indian Affairs enrollment card and posed a provocative question: could he seek reparations from the Jamestown Tribe for the 1868 Dungeness Massacre, when S’Klallam warriors killed members of his ancestral nation?

His question highlights the uncomfortable complexity of historical accountability, tribal relations, and modern identity. It challenges the simplicity of today’s rhetoric around reparations and reminds us that history rarely fits clean political narratives. The past doesn’t divide neatly into victims and villains—and those moral contradictions still echo in the present.