When Sheriff Brian King told the County Commissioners that Clallam County has just 0.8 deputies per 1,000 residents—far below the national average of 2.4—it wasn’t just a statistic, it was an explanation. From convicted felons to sex offenders who fail to register, our county has become a magnet for those escaping justice elsewhere. The question isn’t how they get here—it’s why we keep letting them stay.

A safe harbor for the wrong people

Clallam County continues to be a refuge for those running from the law. Sheriff King reported during a recent work session that Clallam County has 0.8 deputies per 1,000 residents, far below the national average of 2.4. Washington State ranks dead last in law enforcement per capita—51st out of 50 states plus D.C.

The result? A county that’s struggling to keep up with its own criminal population, while becoming a landing spot for offenders from across the region.

From “Abducted in the Woods” to the jailhouse

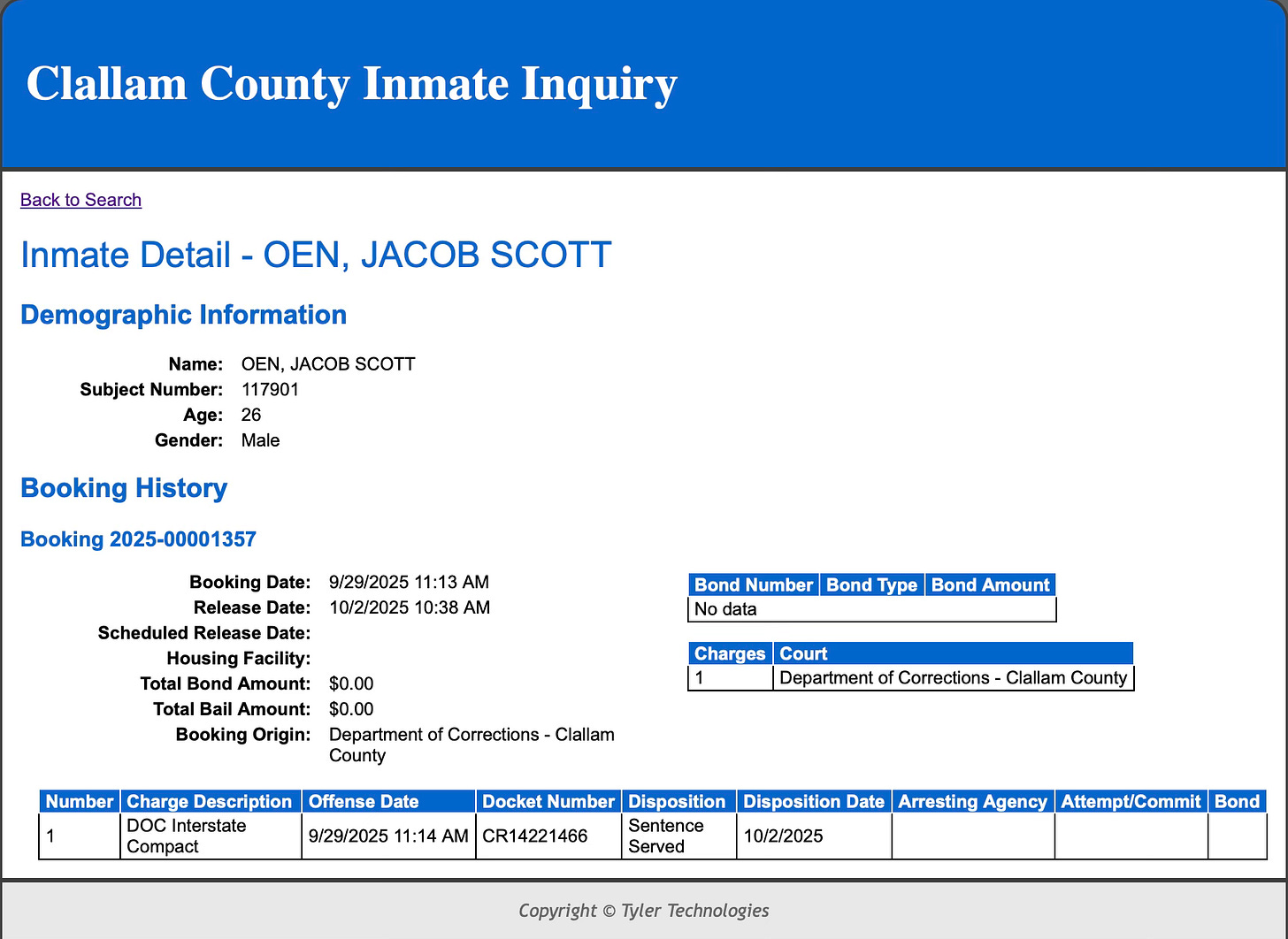

On September 29, 26-year-old Jacob Oen was booked into Clallam County Jail for a Department of Corrections interstate compact violation.

Just four months earlier and nearly 500 miles away, Oen had made headlines in Pend Oreille County after hosting a rave-style event called “Abducted in the Woods” at a rural property outside Newport, WA. Deputies responded to repeated noise complaints after the music—advertised as a “transformative festival of EDM, elevation, and energetic alignment”—continued through the night despite citations and warnings.

Sheriff Glenn Blakeslee said the festival could be heard more than a mile away and had no permit. Oen was arrested and briefly held on a $500 bond.

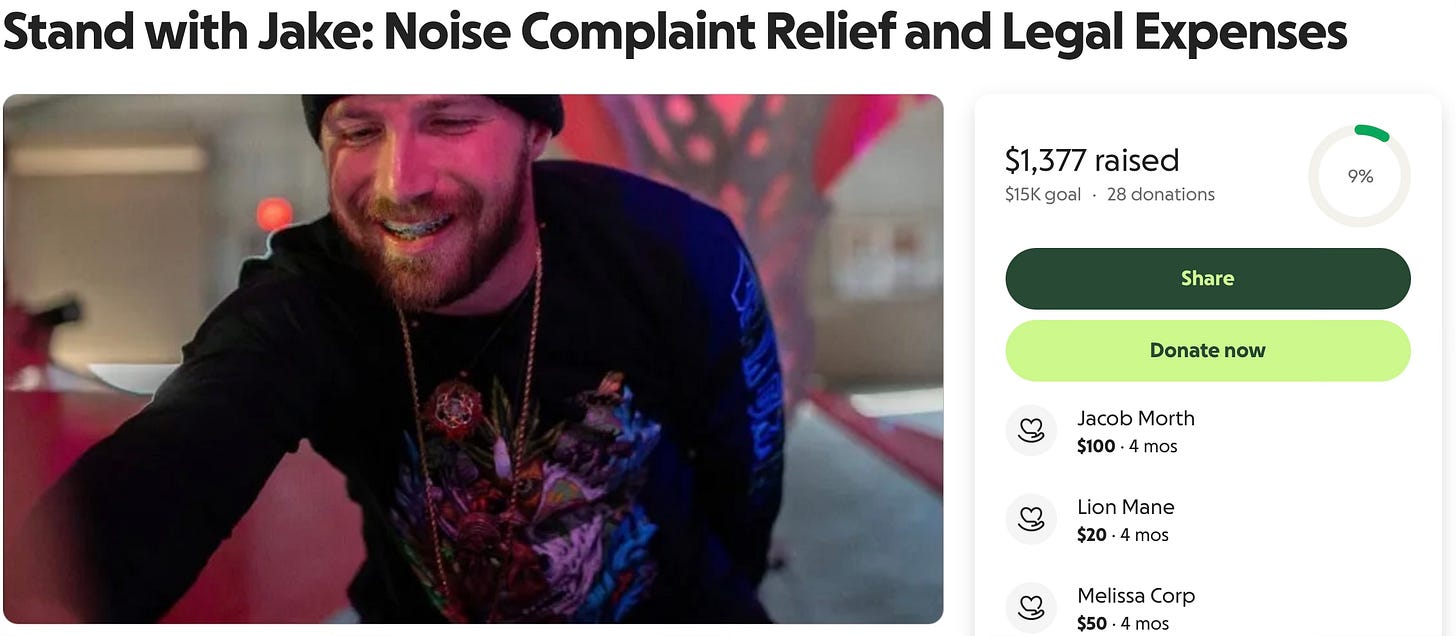

Supporters later launched a GoFundMe page explaining that “All the greats have rap sheets,” raising $1,377 to help with his legal expenses—while vowing to keep the “Abducted” parties going.

Now, Oen has resurfaced in Clallam County custody. It raises the question: why do offenders from other counties and even states find their way here—and stay?

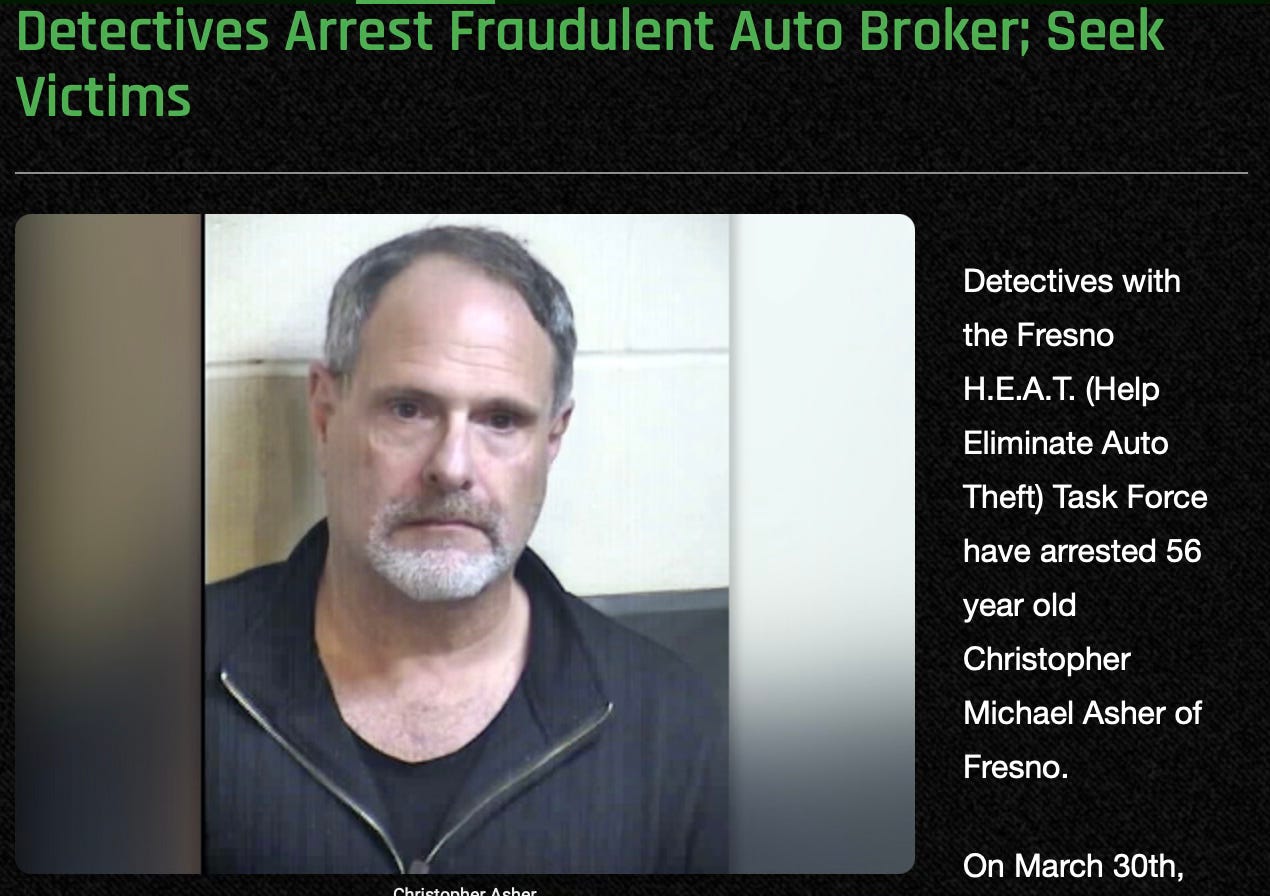

From Fresno to Port Angeles: Another “local” headline

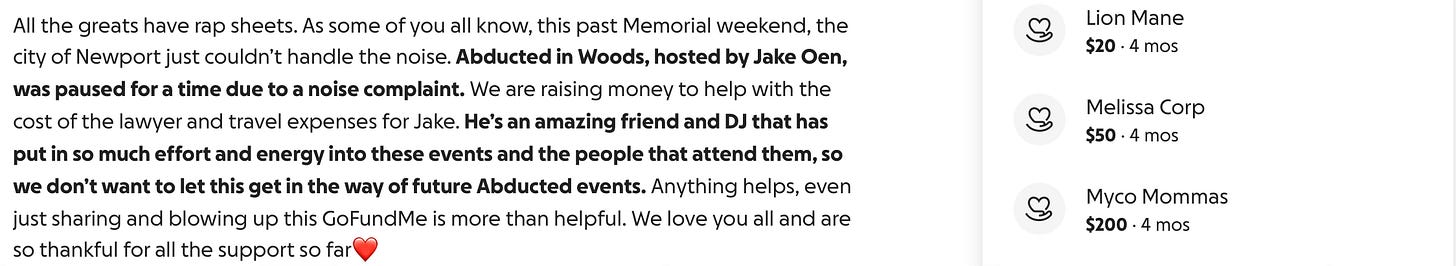

On October 6, Christopher Michael Asher, 59, was booked into the Clallam County Jail on multiple felony charges:

Forgery

Identity Theft

Theft of a Motor Vehicle

Fugitive from Justice in Another State

In 2023, Fresno County, California detectives had arrested Asher for an elaborate auto theft and finance scam. He allegedly forged a dealer’s license using another man’s identity, sold vehicles he didn’t own, and scammed victims out of thousands. His bail in Fresno was set at $117,000—which he posted before disappearing.

On May 19, deputies seized a stolen car from Asher’s home in Port Angeles. He handed over the keys and admitted he hadn’t paid for the vehicle from Koenig Subaru. Despite this, he remained free in the community for months. The case was referred to the Clallam County Prosecutor’s Office with probable cause for theft of a motor vehicle and forgery — yet Asher was still active around Port Angeles until October, when authorities in Fresno, California contacted local law enforcement about his ongoing fraud cases.

Asher is another imported criminal, one of many who’ve figured out that Clallam County’s soft landing makes it a good place to hide out or start over.

Even the Sheriff’s Office admitted that Asher’s history spans multiple states and convictions. Fresno detectives said there are likely more victims who haven’t yet realized they’ve been scammed.

The familiar face of failure: A transient sex offender

Then there are the transients—those who drift from city to city with no fixed address.

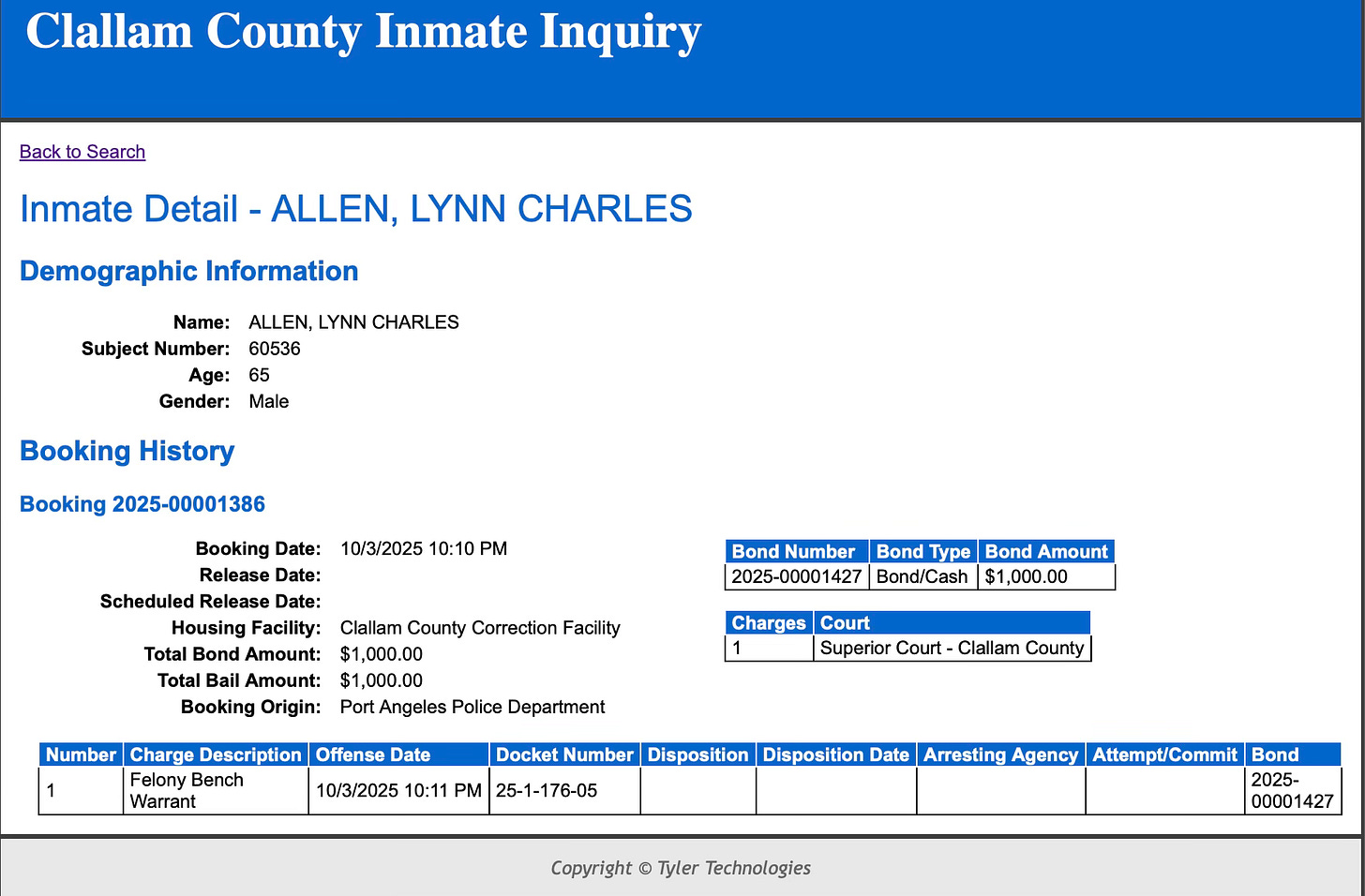

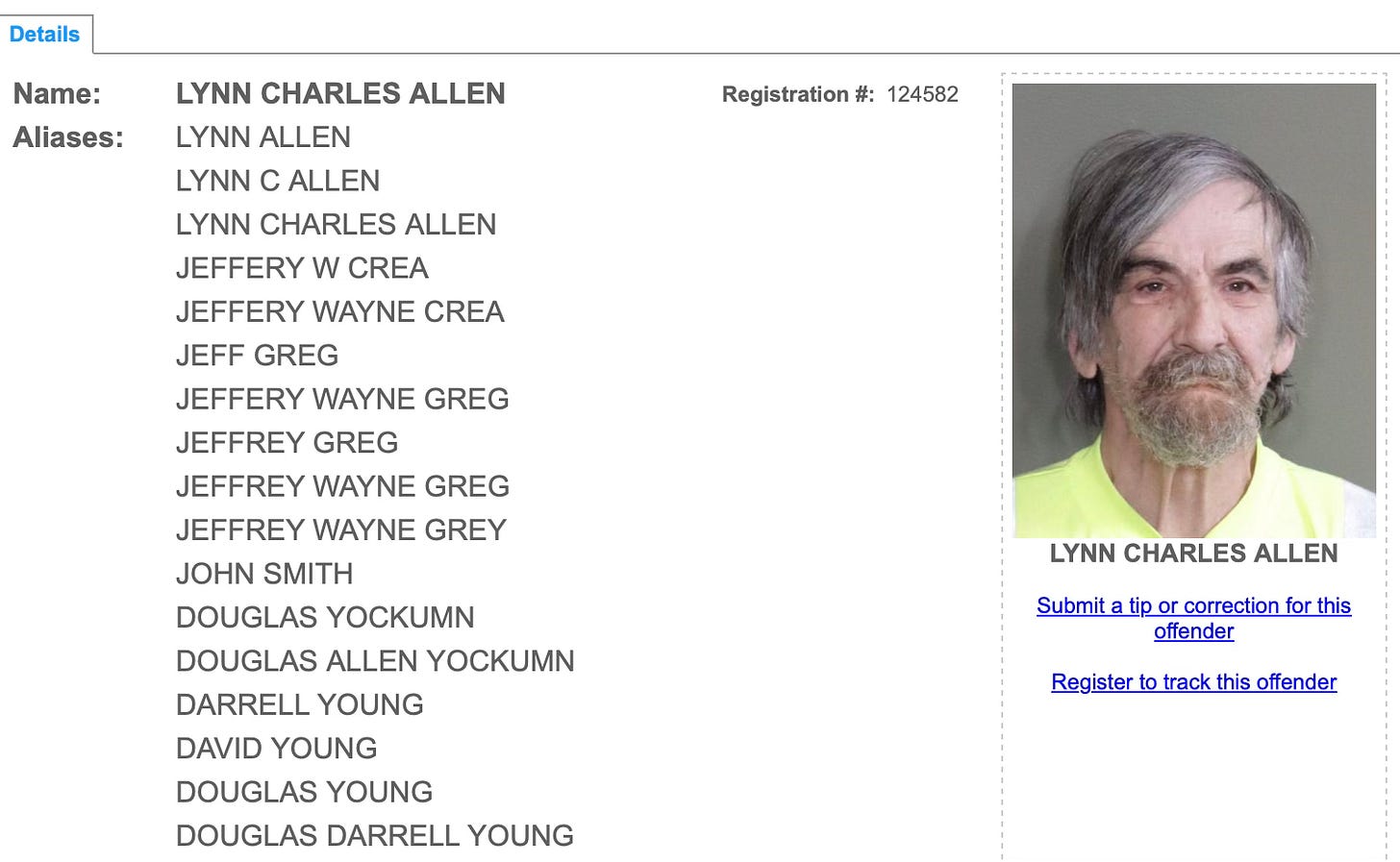

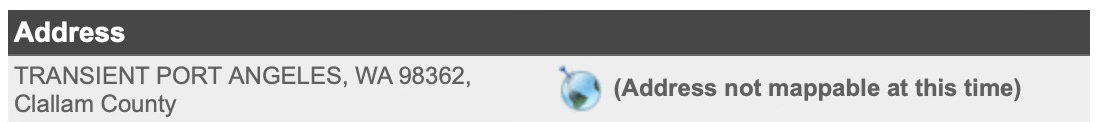

On October 3, Lynn Charles Allen, age 65, was booked into Clallam County Jail on a felony bench warrant. His record includes:

Child molestation (third degree)

Communication with a minor for immoral purposes

Repeated failures to register as a sex offender

According to his sex offender registry profile, “Allen has a history of sexually offending against minors ages 3 months to 18 years.” That means one of his victims was just a three-month-old infant — a horrifying reminder of how dangerous repeat offenders like Allen can be when left unmonitored.

Allen’s past convictions date back to 2003, and his victims include three known juvenile males. Though previously registered in Spokane, offender databases list him as “transient, Port Angeles, WA 98362.”

Locals may recognize Allen from his association with a black spray-painted RV, often stationed near public parks and known drug hotspots. He’s been heard on local scanners and frequently listed as “failure to register” in eastern Washington—yet continues to roam freely here.

A county at the crossroads

When offenders from across the region can settle in Clallam County without consequence, that’s not an accident—it’s a policy failure.

A chronic lack of deputies, minimal state support, and a justice system more focused on “rehabilitation” than protection have created a perfect storm. Instead of prioritizing public safety, the system seems designed to absorb offenders who’ve worn out their welcome elsewhere.

As Sheriff King’s numbers made clear, Clallam County isn’t just under-resourced—it’s undefended. And while the commissioners debate climate resolutions and proclamations, the real crisis—the safety of our residents—keeps getting pushed aside.

And now the County Commissioners are dangling the fear of cuts to public safety, threatening to axe deputies if voters don’t approve a property tax hike — all while finding money for a poet laureate, pizza for drug addicts, and private security for Charter Review Commissioner Jim Stoffer.

“Please support the modest Clallam County general fund levy lid lift this November so we can maintain service across all departments, from Sheriff’s deputies to Public Health to Community Development to elections. The county has worked very hard to cut costs and build efficiencies, but without additional support from you, we will be forced to consider additional painful cuts.” — Commissioner Mark Ozias

Until Clallam County prioritizes law enforcement staffing and holds offenders accountable, we’ll remain a magnet for fugitives, fraudsters, and predators. The people who play by the rules deserve a county that protects them—not one that shelters those who don’t.