As tribal bloodlines thin and policy debates grow louder, it's time to ask whether the boundaries we draw around ancestry still serve justice—or simply preserve power.

Like many who now call Sequim home, Al Courtney didn’t grow up here—but once he arrived, he knew the stories of how the town came to be were worth preserving. In 2000, he helped collect oral histories that were published as Sequim: Pioneer Histories from 1850 to WWII, followed by a second volume covering up to 1962. These books are more than local trivia—they trace names, families, and how small-town bonds shaped a community.

Reading through those histories, many residents might be surprised at how interconnected the past is with the present. You start to see how family lines run through multiple generations, how local surnames came to be, and how personal narratives overlap.

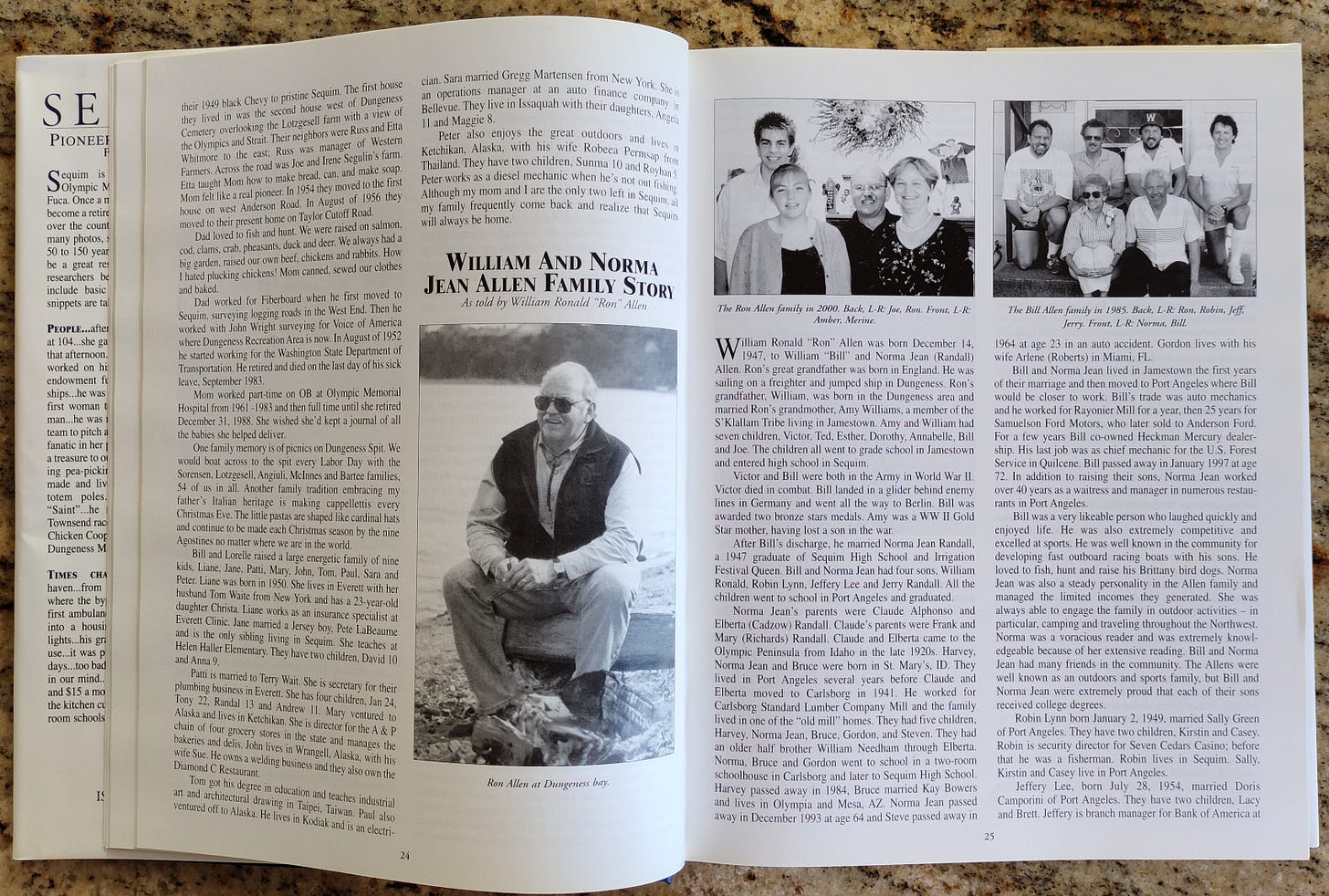

One account tells the story of a young man from England who jumped ship in Dungeness and started a new life in the Pacific Northwest. The Englishman’s son, William, married a woman of Jamestown S’Klallam descent. Their son, Bill, was born in the area and later served in World War II, landing a glider behind enemy lines in Germany. He returned home, raised a family, and passed on his name to the next generation. That name? William Ronald Allen.

Yes—that Ron Allen. The longtime chairman of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe.

According to the Pioneer Histories and public records, Allen’s great-grandfather was a British sailor; his grandmother was Jamestown S’Klallam. That makes Allen one-quarter Jamestown S’Klallam by blood. His children are one-eighth—just enough to meet the threshold for tribal citizenship. If he has grandchildren, now part of the rising generation, they fall below that threshold.

This raises a complicated and increasingly common question: What does it mean to be "tribal" in 2025? According to the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s constitution, full citizenship is limited to those with at least 1/8 tribal blood. (JST Enrollment Code)

Those with less may not qualify—unless the Tribal Council, in its discretion, chooses to adopt them based on “significant community relationship.”

It’s not an uncommon situation, and Allen is by no means alone. Many leaders and members of tribes across the country find themselves navigating the same identity tightrope. But when people who are mostly non-Native by ancestry continue to receive exclusive rights—land transfers, tax exemptions, and legal carve-outs—it’s fair to ask: Is this about heritage, or something else?

Between sovereignty and citizenship

Native American tribes are sovereign nations, with the right to self-govern and set their own membership rules. That sovereignty comes with both privileges and responsibilities. In Clallam County, we see tribal governments managing businesses, overseeing health services, negotiating environmental policy, and acquiring land.

But there’s an undeniable tension between sovereignty and shared governance. Tribal members are also U.S. citizens, voting in elections, receiving federal benefits, and participating in public life. This dual status can create confusion—and sometimes, inequity.

When tribal entities purchase land and move it into trust, those properties are often removed from local tax rolls. When tribal fisheries claim subsistence rights, they may use methods and technologies far removed from ancestral traditions. When permits and projects are contested, environmental rules may apply differently depending on who owns the land.

None of this is to dismiss the deep trauma and historical injustices faced by Native communities. But as time moves forward and ancestral bloodlines become increasingly blended, the systems designed to address that trauma deserve honest review.

The future of identity

Many tribal members and leaders have started this conversation themselves. Some argue that strict blood quantum rules were imposed by the U.S. government in the first place—tools of control rather than tradition. Others point out that lowering the threshold for citizenship would mean expanding benefits and services, potentially straining limited resources.

In a past tribal council campaign, Jamestown member Thaddeus O’Connell openly criticized the blood quantum system, calling it a legacy of white supremacy and eugenics. “There is nothing on the Lord’s beautiful Earth that makes me twice as S’Klallam as my children,” he wrote, adding that using DNA percentages to determine citizenship was never a tribal value to begin with.

“As long as we use arbitrary social constructs based in white supremacy to determine Tribal citizenship, we rob ourselves of long term dedicated participation of community minded individuals while relegating Tribal "descendants" to living as an under-class within our Tribal community.” — JST member Thaddeus O’Connell during his 2021 campaign for tribal council

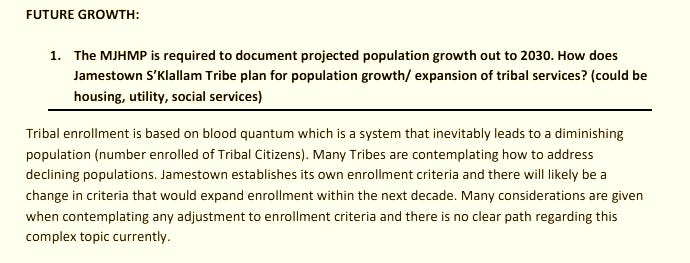

Even the Clallam County Hazard Mitigation Plan acknowledges this issue, noting that current enrollment rules will likely change in the coming decade as tribes consider how to maintain cultural continuity amid declining bloodlines.

Converge Media’s film “Nooksack 306” highlights the ongoing struggle of Indigenous families who have been disenrolled by tribal authorities, facing eviction from homes they’ve long occupied. These disenrollments have split families and ignited a multi-generational fight for justice and belonging.

Allen himself has acknowledged the demographic trends, and under his leadership the Tribe has explored ways to balance community participation with legal eligibility. Other Jamestown officials, like Latisha Suggs, have expressed support for lowering the blood quantum threshold to ensure that descendants who are actively involved in tribal life aren’t excluded based on a technicality.

“I support lowering blood quantum for citizenship. The path to make this happen will come from community input and discussion along with analysis of how this change will impact existing services, & how those services will change to meet the needs of a larger population. I also feel it is vital to maintain the level of service to our existing population while looking at ways to expand citizenship. The Tribe should be inclusive of direct Jamestown S’Klallam descendants who are actively involved in our community.” — Latisha Suggs during her 2024 campaign for tribal council.

Where we go from here

Today, there are people in Clallam County who are legally considered tribal citizens, because they have at least one-eighth Native ancestry. There are others, deeply connected to the community and the culture, who are excluded by a technicality. And there are citizens—tribal and non-tribal alike—who wonder whether public policy should hinge so heavily on something as complex and fluid as genealogy.

We live in a moment when race, history, and identity carry enormous weight in policy and politics. But we also live in neighborhoods, go to the same stores, attend the same schools, and share the same roads. As tribal communities grow more diverse by blood and more integrated into public life, we should be willing to ask hard questions—without blame, but with clarity.

Are the rules we follow today truly rooted in equity? Or are they increasingly shaped by legal and political strategies that no longer match our shared realities?

No matter where our great-grandparents came from, most of us in Clallam County have more in common than not. Perhaps it’s time to revisit the lines we draw—and ask who they really serve.

Last Sunday, readers were asked if future tribal-county projects should require third-party oversight to ensure public safety, transparency, and cost control. Of 177 votes:

100% said, “Yes, absolutely”

0% said, “No, current process is fine”

0% said, “Only on flood/safety projects”