Clallam County Public Health claims to protect our community—but its 2024 report reveals a different mission: reconciliation programs and “harm reduction” policies that enable addiction rather than prevent it. From free pizza parties for addicts to county-sanctioned meth pipes, Narcan, and even “boofing bags,” downtown Port Angeles has become an open-air drug market. One resident’s Saturday morning walk exposes the devastation: overdosed bodies, drug trafficking hubs, and neighborhoods terrorized while county leaders call it compassion. Is this public health—or government-assisted suicide?

It’s important to understand what Clallam County’s Public Health Department says its mission is—and what it isn’t.

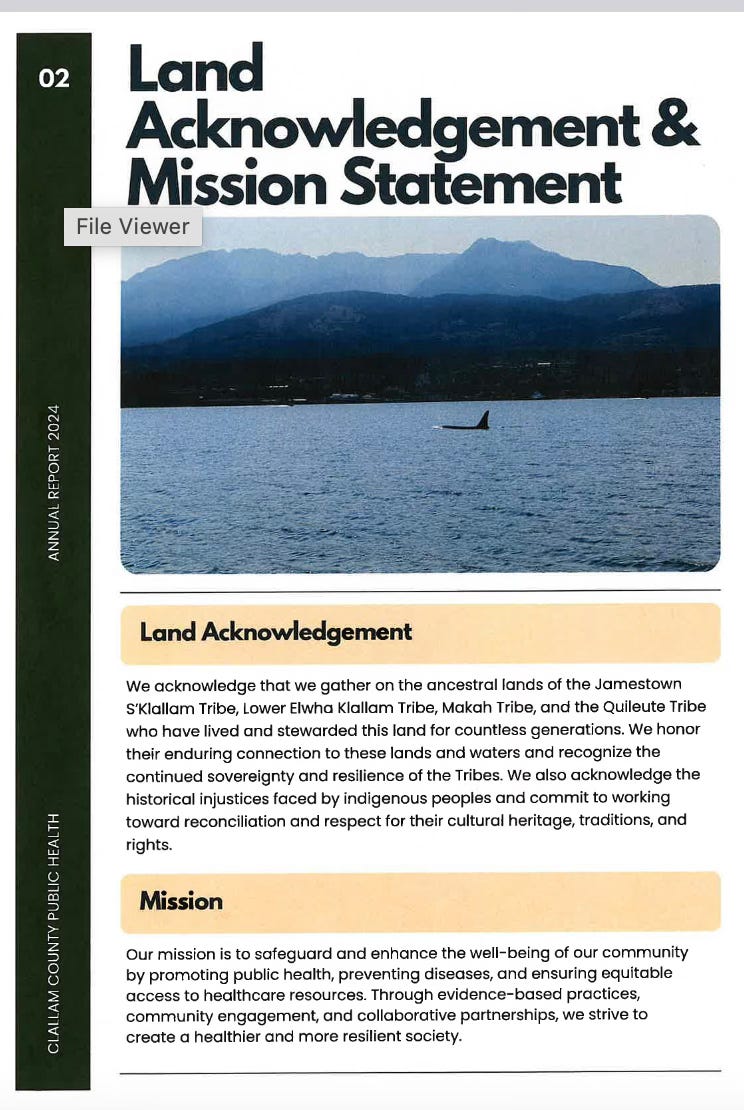

In its 2024 annual report to the Board of Health, the department lays out its guiding priorities. And before any mention of disease prevention, child health, or community safety, the document begins with a land acknowledgement. On page two, just after the table of contents, the report declares:

“We acknowledge that we gather on the ancestral lands of the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Makah Tribe, and the Quileute Tribe... We honor their enduring connection... and recognize the continued sovereignty... we also acknowledge the historical injustices faced by indigenous peoples and commit to working toward reconciliation and respect.”

There it is, in black and white: reconciliation—not public health—is Clallam County’s first stated objective. That may sound poetic on paper, but in practice, it means taxpayer-funded reparations programs and policies that have nothing to do with health outcomes.

Once you accept that public health has been redefined, the rest of the picture comes into focus—especially the county’s aggressive embrace of “harm reduction.”

Harm reduction Fridays, devastating Saturdays

One Port Angeles resident recently described what she sees every Saturday morning downtown after the county’s Harm Reduction Center has handed out supplies on Friday. The center draws addicts in with free pizza, then distributes needles, Narcan, meth pipes, crack pipe cleaning kits, and even “boofing bags” so users can administer street drugs rectally for a more intense high—all with the blessing of three county commissioners.

Her account, shared after a walk through downtown this last weekend, paints a bleak picture:

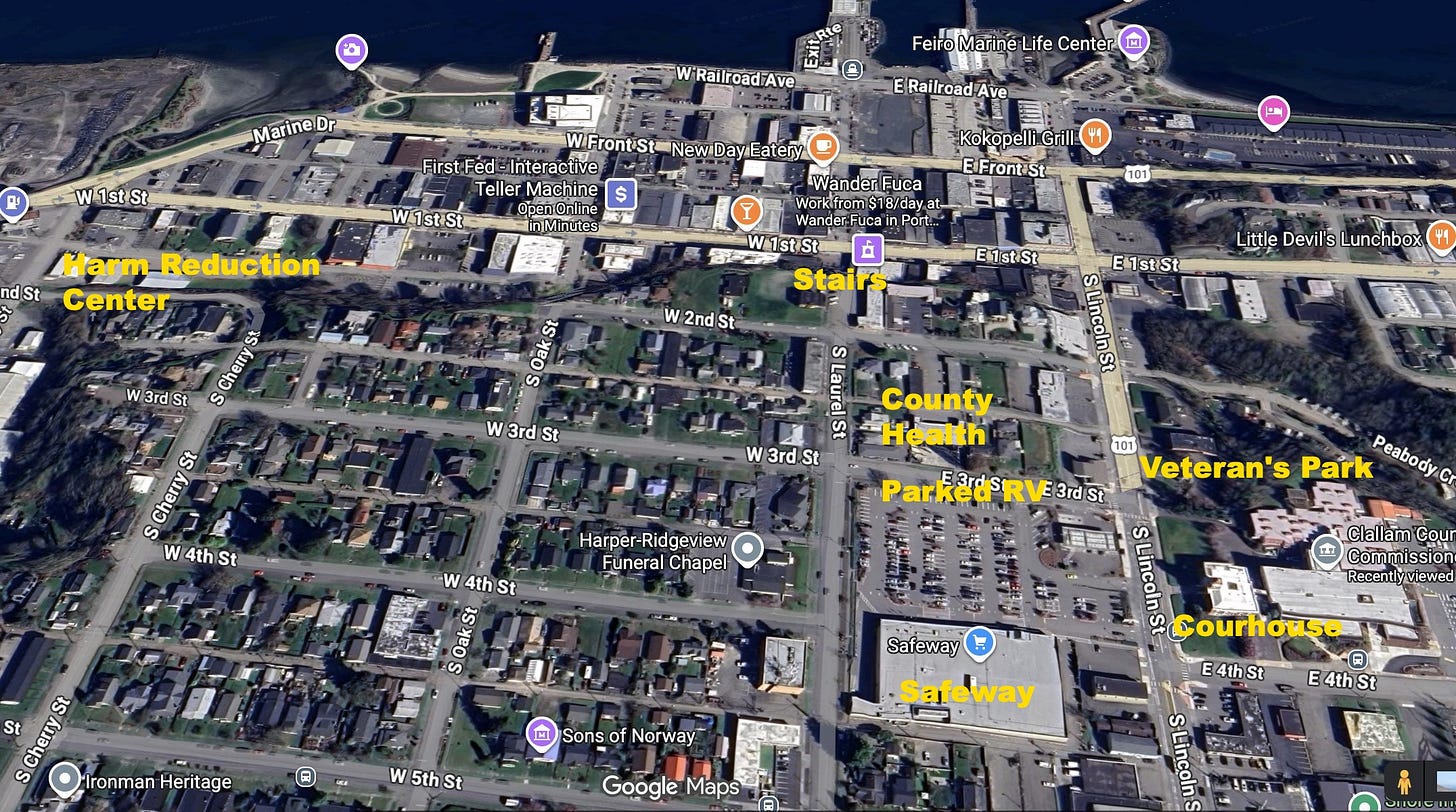

“Saw quite a few of these same black-and-blue umbrellas around… are they on the [harm reduction center] ‘menu’? Being used as a wind/privacy shield for smoking fentanyl on foil. The first few pictures are from 3rd Street by the Clallam County Health Department, the ones with bushes are from Veterans’ Park and the adjacent city-owned building.”

She noted a familiar RV parked across from the health department, with “lots of foot traffic at it.”

“Last night when I left a class downtown, folks were huddled around this pole with phones plugged in somewhere lying on the ground and one guy was standing with them in a fentanyl fold. Not safe to take a pic then, but I walked by it this morning. Interesting—someone left them a motivational note card, but nobody picked up the trash. It’s a charging station for street people, an unattended plug. The note says: ‘Your story is just beginning, keep it up, the best is yet to come.’”

The pattern is familiar: Safeway’s northeast parking lot, the RV near the health department, and nearby stairwells form a circuit of drug use and dealing.

“They strategically place vehicles to obscure the view of the drug trafficking. Seems like a mule holding drugs in one spot, with a foot courier somewhere else across the lot, and a lookout on the stairs up to Laurel. If you look at the layout on Google Maps satellite version, you get the idea.”

She added that even senior citizens can’t walk safely to buy groceries:

“I had a community member tell me recently about how he was walking with a limp and pain to Safeway. One of the guys with a backpack approached him and offered to sell him pills right in the parking lot. They’re literally hanging out there looking for new customers.”

She has seen that same RV before.

“That same RV has been around town for a while. When it was blocking traffic visibility near an intersection back in July , residents asked it to move and the driver said he was out of gas. Then he nodded off. An officer came for welfare check and suddenly the driver found the gas to drive away.”

“On my way home, I went back past the health department. One guy was sitting up but seriously nodding out, his head bobbing uncontrollably. I called down to see if he was okay. He popped his head up and yelled something unintelligible at me, so I didn’t go get Narcan—he seemed hostile. But then his head flopped back down, rolling around again, so I called non-emergency and asked for a welfare check.

“This is the type of daily trauma our “leadership” is inflicting on regular citizens of Port Angeles. Where is the harm reduction for us?”

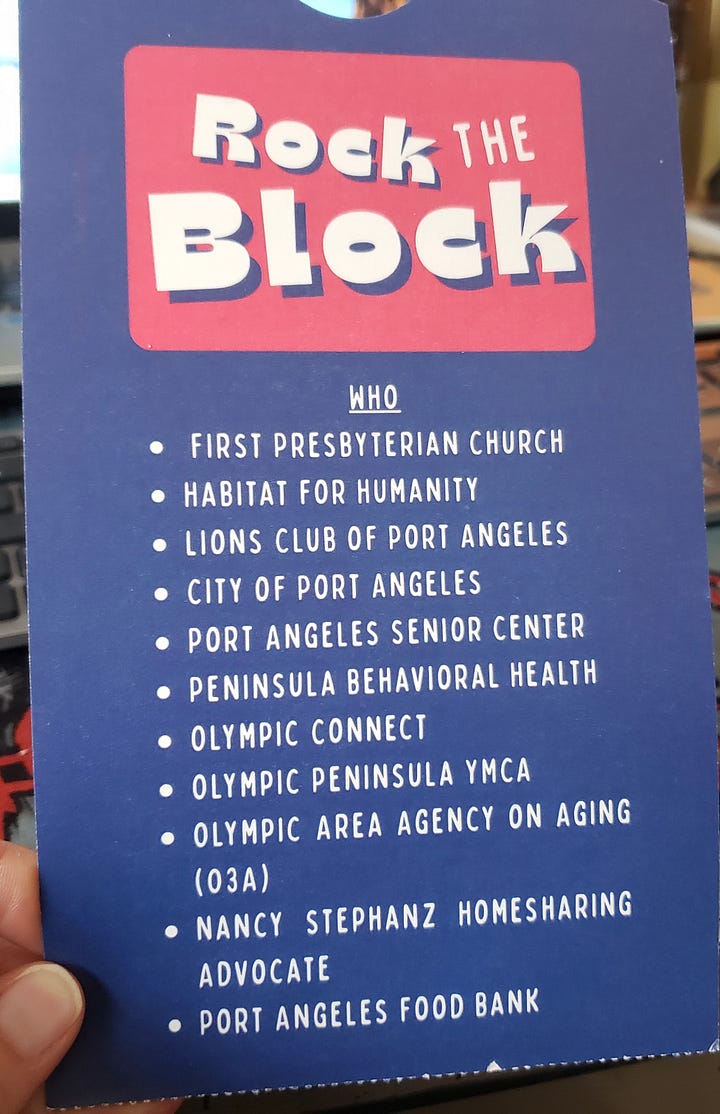

When she returned home from her walk, a flyer was waiting—advertising an event to ‘connect people… to resources specifically supporting… people who are homeless.’ Among the sponsors? The very organizations profiting from the crisis, including Peninsula Behavioral Health and Habitat for Humanity.

Is there an alternative approach?

After sending photos and the description of her walk, she sent a link to what she called “the BEST, most raw and accurate interpretation of what is wrong with the approach to addiction in Washington and what we should be doing instead.”

She’s talking about a powerful conversation between Philip Lindholm and Ginny Burton—a woman who knows the system from the inside. Ginny’s story sounds like fiction: introduced to drugs by her own mother at age seven, she spent decades addicted, homeless, and entangled in crime. By 40, she had racked up 17 felonies and was living on the streets of Seattle. But against all odds, she turned her life around—graduating from the University of Washington as a Truman Scholar and emerging as one of the nation’s most respected voices on addiction and recovery.

In the interview, Ginny dismantles the myths we’re fed about homelessness and addiction. She argues that so-called “harm reduction” isn’t compassion—it’s enablement. Real compassion, she says, is about accountability, structure, and helping people build lives worth living.

From the failures of Washington’s social service model, embraced by Clallam County, to the real dynamics of life on the streets, Ginny’s hard-earned perspective cuts through the political noise. For policymakers, service providers, and community members alike, this episode is essential to watch.

Assisted recovery—or assisted suicide?

Is this harm reduction or government-assisted suicide? Is this solving a problem, or just making it worse?

The county and its partners tout harm reduction as compassionate care. But has the problem improved since the Jamestown Tribe opened its Medication-Assisted Treatment (MAT) clinic, billing $719 per client encounter? Or has the problem worsened?

Every Saturday morning walk downtown seems to suggest the latter.

Port Angeles depends heavily on tourism. Yet instead of clean streets, safe parks, and thriving businesses, visitors now encounter tents on sidewalks, bodies slumped in parking lots, and users revived with Narcan only to return to the Harm Reduction Center for more supplies.

This is the real-world result of county priorities. Not health. Not safety. Not community well-being. But reconciliation programs, tribal partnerships, and harm reduction policies that perpetuate addiction.

After years of the same city and county leadership, residents are left to ask: Is this really the future we want for Clallam County?