Clallam County officials keep asking the public to trust “the experts” while accountability quietly disappears. Costs rise, repeat offenders cycle through the system, and scrutiny is dismissed — leaving taxpayers paying for decisions they never approved.

“Ask the Experts” Isn’t Oversight

An email to Commissioner Mike French pressed him on a very specific claim he made: that the North View luxury permanent supportive housing complex in Port Angeles will serve people not actively using substances, while also asserting Washington landlord-tenant laws “do not allow a landlord to evict solely because of substance use.”

CC Watchdog asked Commissioner French to identify the actual legal authority: which statutes, case law, or formal guidance supposedly prevent eviction in cases of ongoing substance use.

French declined to clarify by email, then addressed it publicly by conceding he’s not an expert in housing law and offering this fallback: “I would invite you to ask the experts… the information that they gave us was, ‘this kind of housing works.’”

That’s the problem. Peninsula Behavioral Health received major public funding for North View, its four-story luxury homeless housing complex, yet its presentations take place during work sessions where public comment isn’t allowed. If residents try contacting PBH directly, PBH has no obligation to respond. When PBH’s claims turn out to be wrong — like the past “dishwashers are required by the state” assertion — the incentive to engage disappears.

That’s not governance. That’s outsourcing accountability.

And it’s exactly how public projects drift into scandal when “nobody is minding the store” — the same failure model residents saw when the William Shore Memorial Pool ended up under state fraud scrutiny (and yes, Commissioners French and Johnson served on that board during the alleged fraud scandal).

Empty Beds, Empty Parking Spots

On an average night, Serenity House reportedly has dozens of shelter beds open — yet the county approved $118,000 for a three-car “safe parking” site at a Sequim church that (so far) hasn’t had a single participant.

So why are people still camping outdoors in Sequim?

At some point, the question stops being “do we need more money?” and becomes: do we need better management and enforcement of what already exists? If capacity is sitting idle while the problem persists, the system isn’t underfunded — it’s underperforming.

The New Tax Push Nobody Mentions Locally

The Washington Legislature is considering HB 2559, which would allow cities and counties (starting April 1, 2027) to impose a local excise tax up to 4% on short-term rentals to fund affordable housing.

In testimony, the Washington State Association of Counties signaled enthusiasm — with a WSAC policy consultant saying counties “love the idea,” even floating that they’d be open to more than 4%.

Here’s the part Clallam County residents should not miss:

WSAC is led by its president, Clallam County Commissioner Mark Ozias. Representing Clallam County on WSAC’s legislative steering committee is Commissioner Mike French. And Clallam County’s WSAC involvement isn’t theoretical — it’s funded by hundreds of thousands of taxpayer dollars through county dues.

So let’s say it plainly: Clallam taxpayers are paying voluntary membership dues to an NGO lobbying apparatus that is advocating for new taxing authority — and two commissioners sit in WSAC leadership circles while not a word of this gets aired in a way that resembles transparent local debate.

That’s not “representation.” That’s using your money to lobby against you.

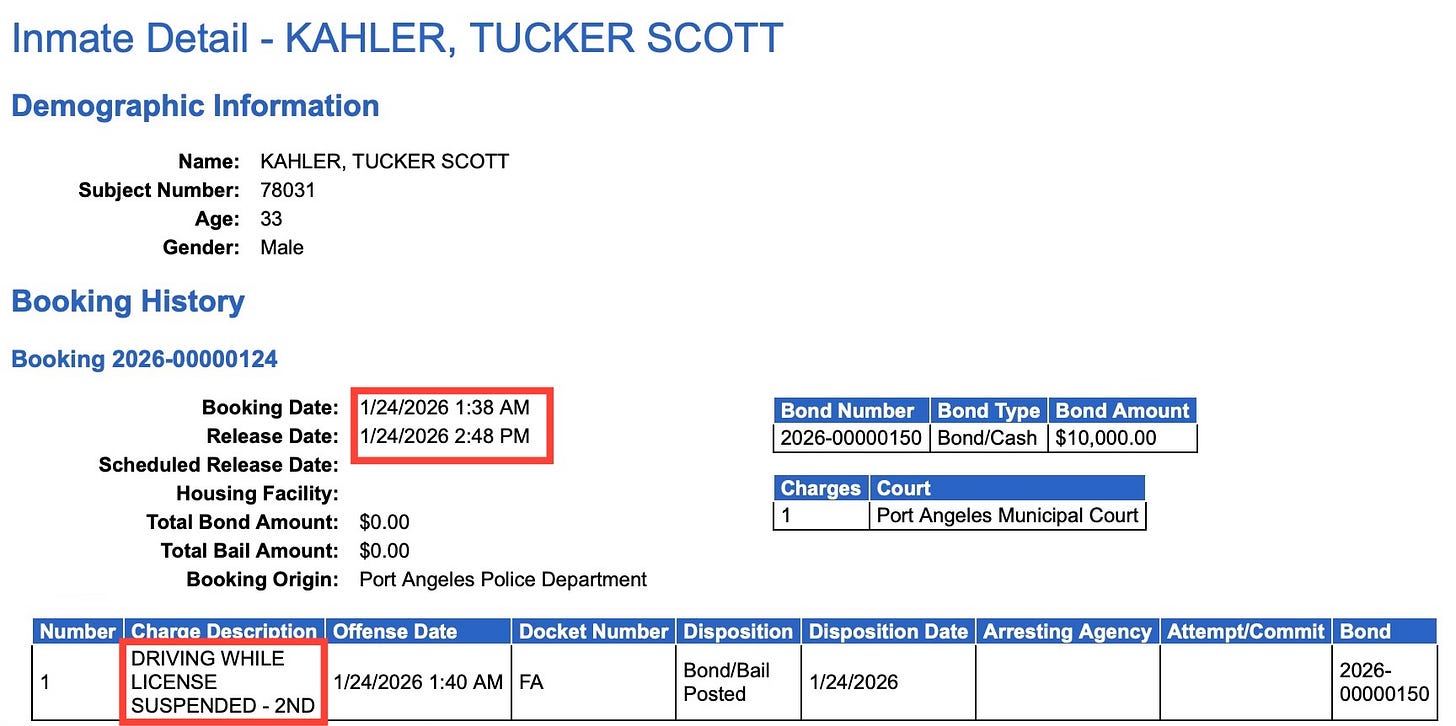

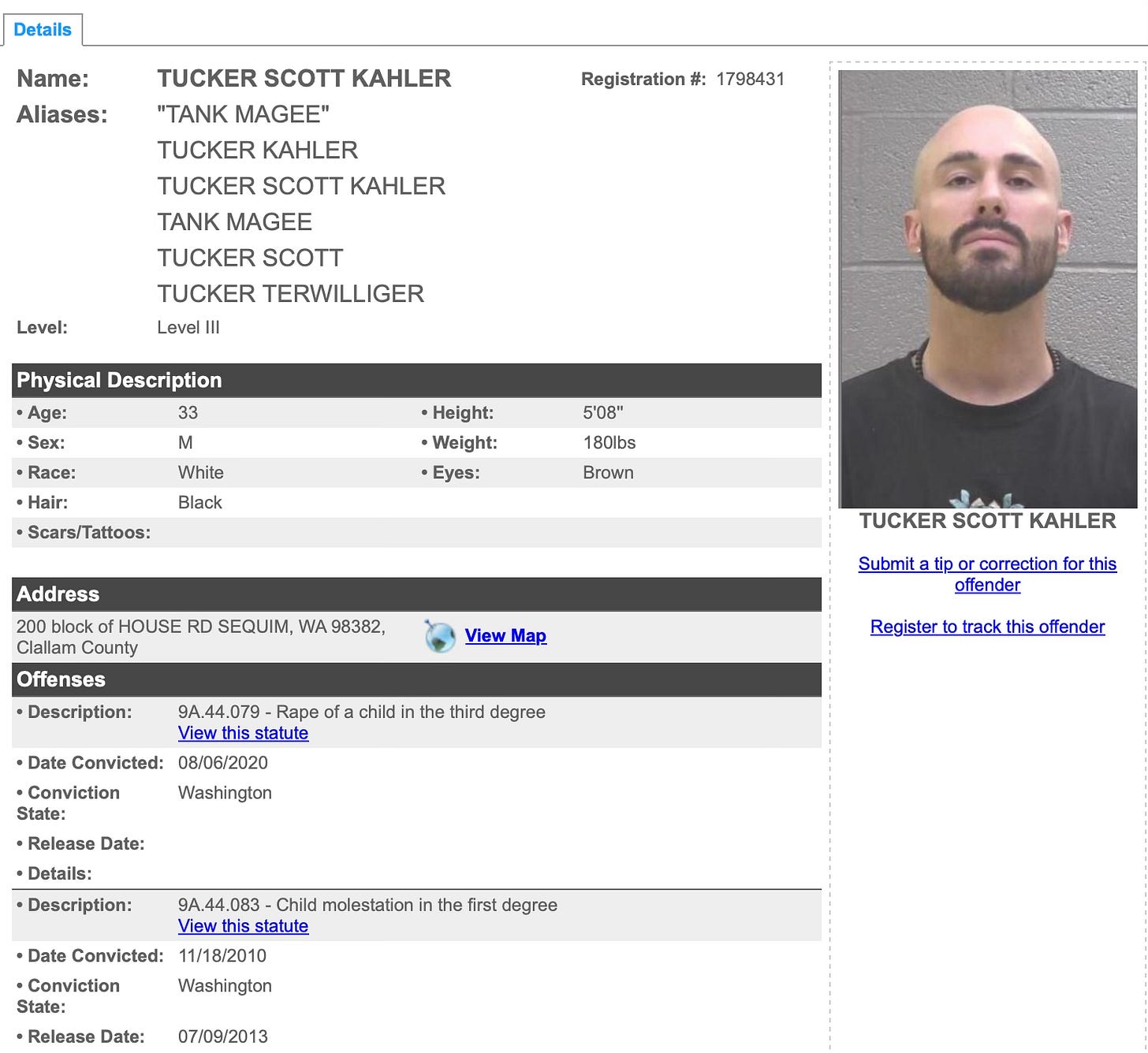

Tucker Kahler: Then and Now

Tucker S. Kahler’s name is back in the recent booking-and-release churn — most recently booked and released the same day on a suspended-license charge.

Here’s the context the public deserves to remember: in September 2020, Kahler was sentenced to four years in prison for third-degree rape of a child (a 14-year-old).

The sentencing judge called the behavior “predatory,” and prosecutors flagged him as a repeat offender.

This is why “catch and release” isn’t an abstract policy debate. It’s a real-world public safety posture — and the community is forced to live with the consequences.

Clallam County Court Chaos

If you rely on legacy outlets, you’re missing a growing body of court reporting from The Olympic Herald that raises serious questions about discretion, insider relationships, and taxpayer-funded decision-making in Clallam County. The pattern is simple: key choices are made behind closed doors, scrutiny is brushed off or attacked, and the public pays for every delay — without ever being asked.

Here are stories from just the past few days:

Judge Basden Appoints Close Friend to Represent Fisher

Judge Brent Basden selected longtime friend and former law partner Lane Wolfley to represent murder defendant Aaron Fisher at $250/hour, while also presiding over the case. The Herald questions why a close associate was chosen over neutral alternatives — and why taxpayers must absorb the cost.

Basden’s Friends Rally in His Defense

Following the reporting, a Change.org petition emerged, and personal allies publicly defended Basden. The Herald notes that loyalty does not resolve conflict-of-interest concerns and instead reinforces insider optics.

Basden Calls Press “Cyberbullies”

From the bench, Basden labeled investigative scrutiny “cyberbullying.” The Herald frames this as an attempt to shift focus away from ethics and spending questions.

Appellate Courts Repeatedly Reverse Basden Rulings

The Herald documents multiple appellate reversals tied to jury instructions, juror handling, and improper fees. The takeaway: judicial errors cost taxpayers twice — once at trial, again on appeal.

Fisher Trial Delayed to February 9

Basden granted a continuance requested by Wolfley, pushing the Fisher trial back two weeks. The Herald again highlights the cost of delay and the appearance issues surrounding Wolfley’s overlapping compensation arrangements.

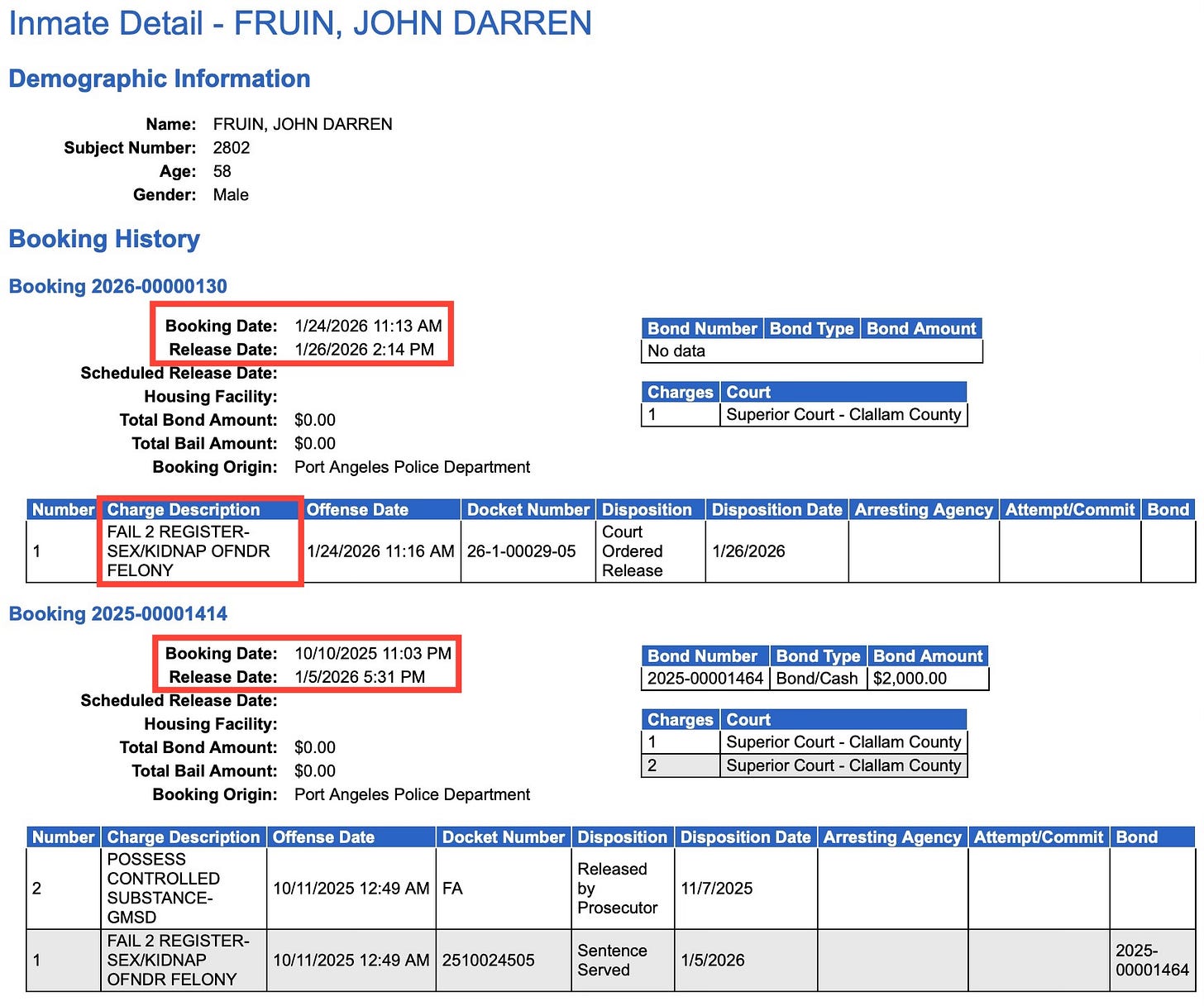

Fruin Returns

Remember John Fruin — the out-of-state sex offender from Oregon who landed in Clallam County jail in October on failure-to-register and drug possession charges.

He was released on January 5, then booked back into Clallam County jail on Saturday on felony failure-to-register sex offender charges — and released again yesterday.

Here’s the question the county never wants to answer out loud: how many times do we “process” the same people before someone admits this isn’t management — it’s a revolving service counter? Booking, medical screening, meals, transport, court time, paperwork, prosecutor review — all public expense. And while residents are told “the system is complicated,” the lived reality is simple: repeat churn, repeat costs, repeat risk — with no measurable deterrent.

Three Bookings, Zero Consequences

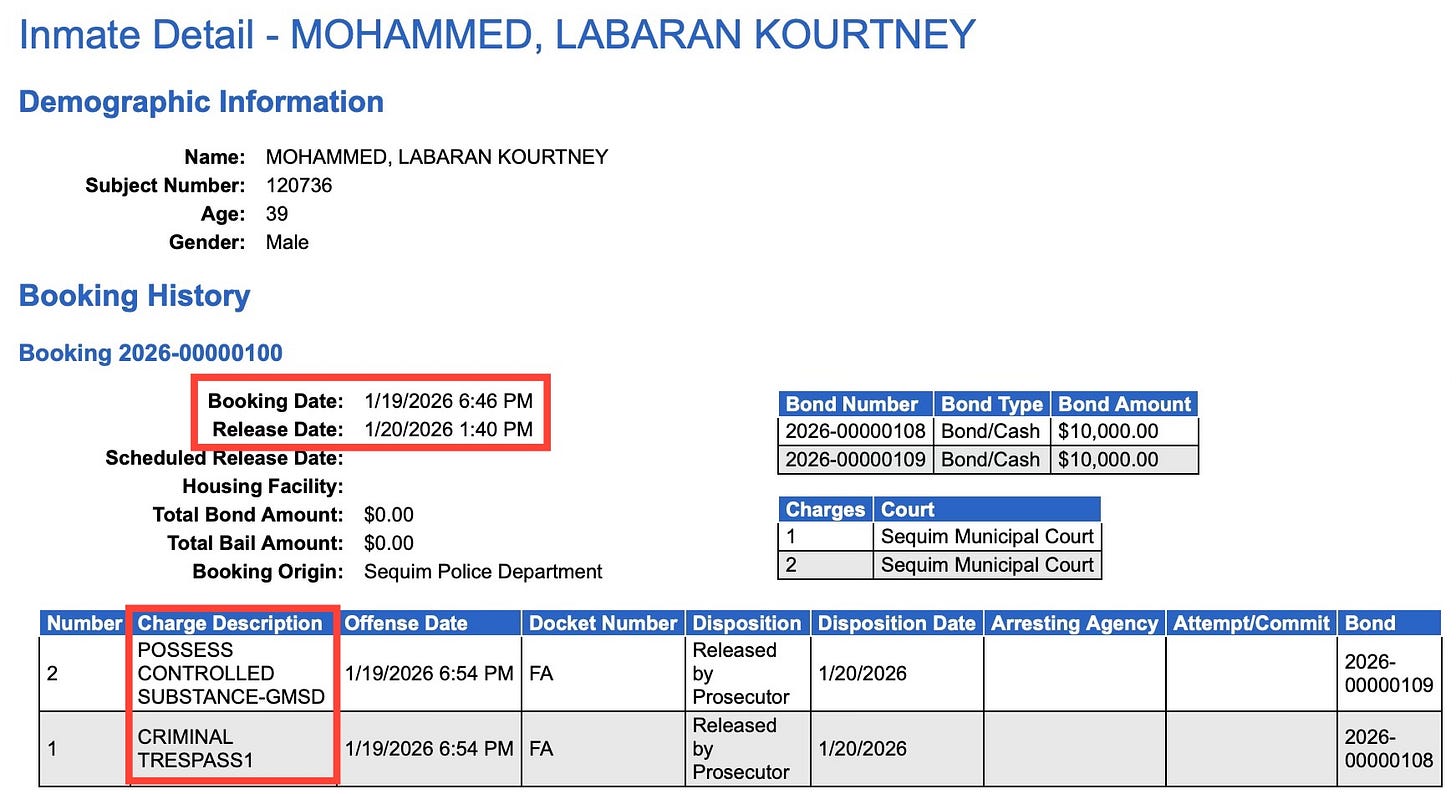

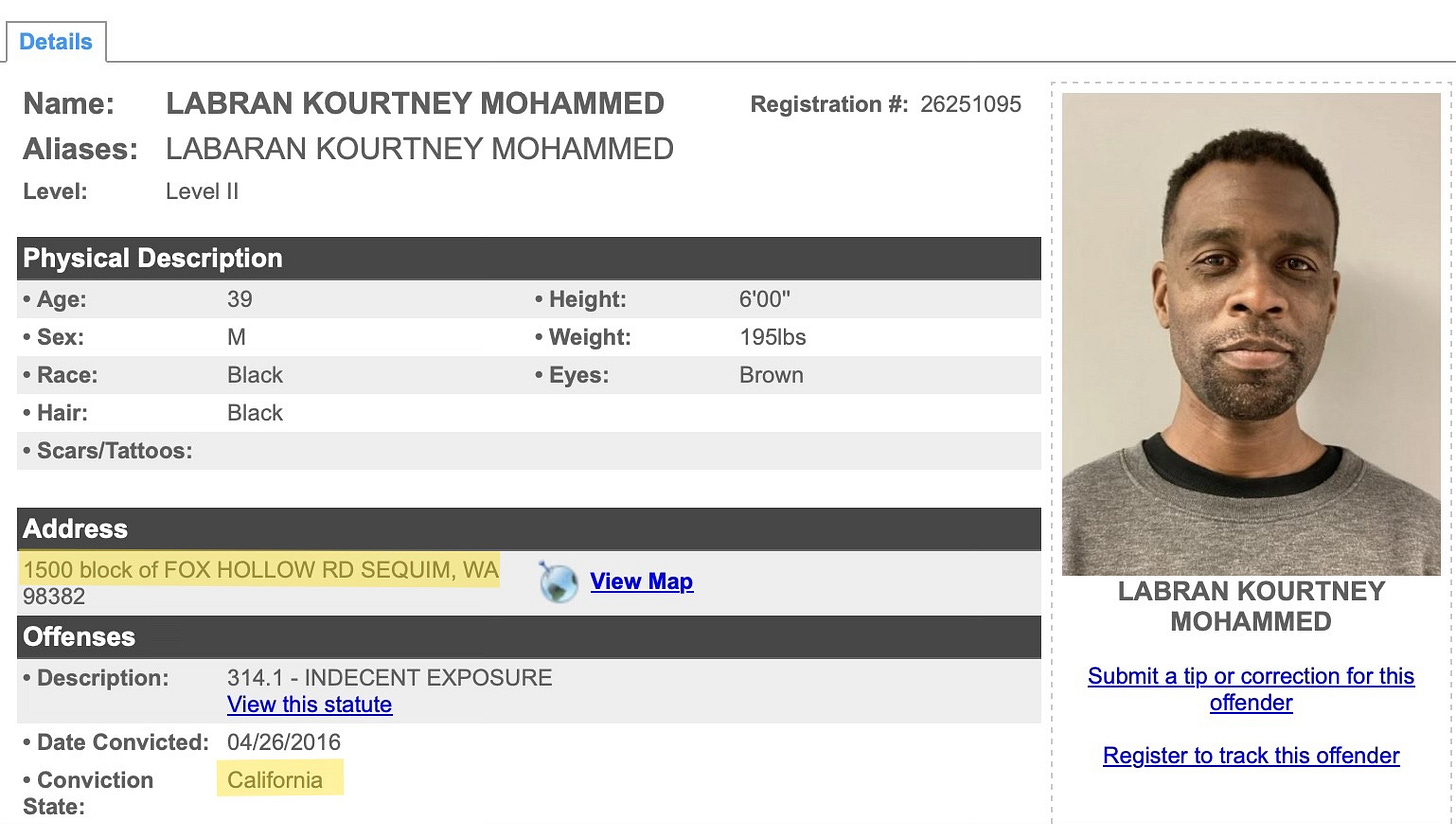

Labaran Kourtney Mohammed was booked into Clallam County jail on January 19 for possession of a controlled substance and criminal trespass — and released by the prosecutor the very next day.

Mohammed, a registered sex offender from California, is not new to the system here. In November, he was arrested on drug-related charges, and in December, he was booked and released again for a drug-related DUI.

That makes three drug-related bookings in roughly three months. None of it appears to have changed the behavior. None of it appears to have imposed meaningful consequences.

This is what life looks like in a county fully committed to “harm reduction” without accountability. Mohammed didn’t invent the system — he adapted to it. Free food, free shelter, free transportation, free drug supplies, and even taxpayer-funded instructions on safer drug use create a predictable outcome: repeat offenses with no deterrent. And every step of that cycle is paid for by the public, whether they consented to it or not.

When NGOs Become the Newsroom

The media used to be called the Fourth Estate — an independent check on government power. Local newspapers once did the unglamorous but essential work of asking uncomfortable questions, following money, and clearly labeling opinion, advocacy, and advertising.

That line has blurred beyond recognition. County commissioners now publish glowing write-ups about county “successes” without clearly disclosing their elected role. Advertisers are allowed to submit promotional content that mimics reporting, marked only by a faint “paid advertisement” disclaimer. And now, nonprofits that receive millions in taxpayer funding are writing articles telling the public how important they are — without disclosing who they are.

The CEO of Habitat for Humanity of Clallam County recently authored an article celebrating a housing milestone, yet nowhere did it disclose that she is the organization’s chief executive. An article praising the Boys & Girls Club of Sequim was written by Mary Budke — again, without identifying her as the CEO. These aren’t neutral observers; they are recipients of public money shaping the narrative about themselves.

When NGOs become both the subject and the author of coverage, and disclosure disappears, the public loses its ability to distinguish reporting from promotion. And when that happens, democracy doesn’t fail loudly — it fades quietly.

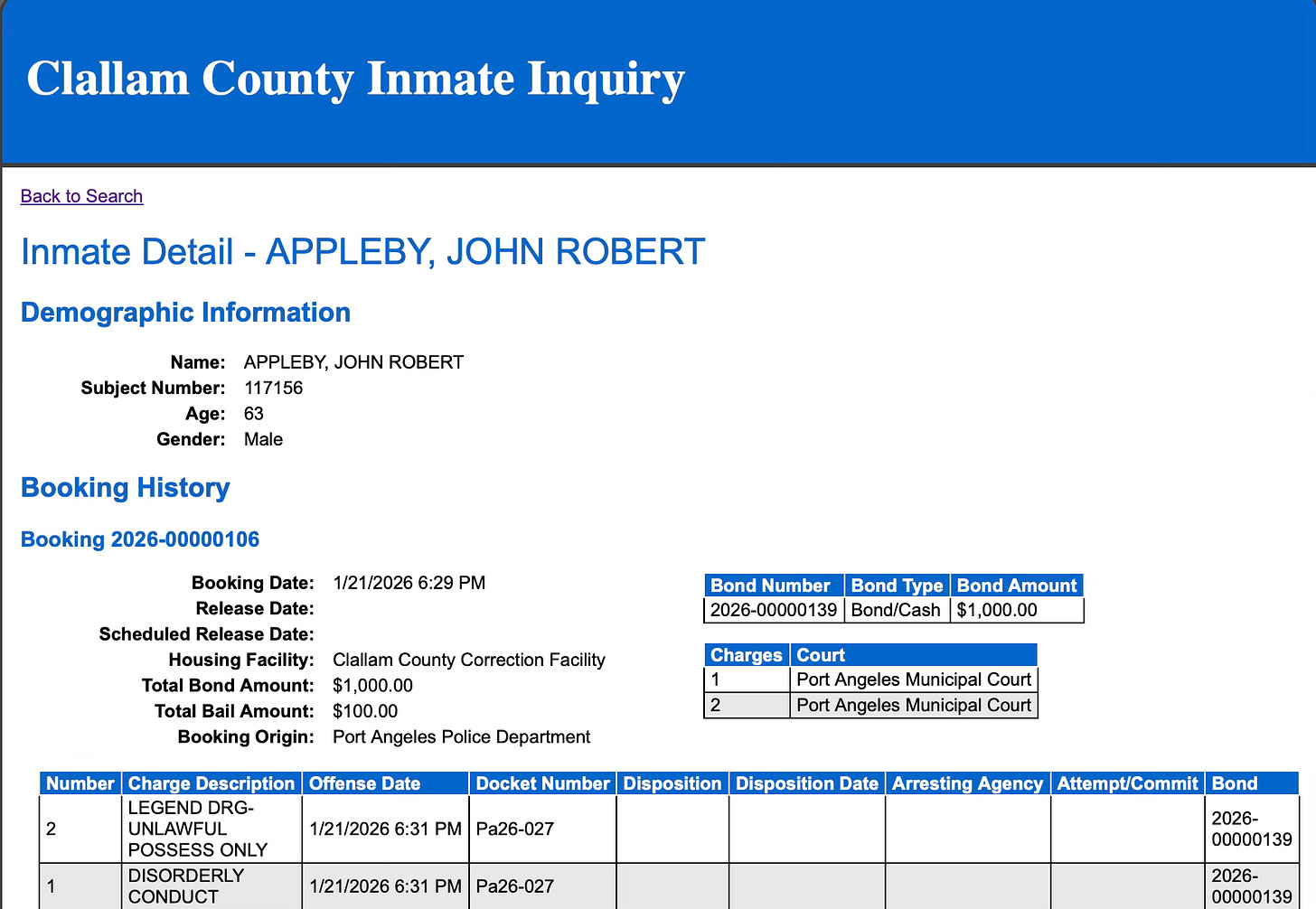

Another Frequent Flyer

John Robert Appleby, age 63, was booked into Clallam County Jail last week for unlawful drug possession and disorderly conduct.

A quick look beyond county lines shows a familiar pattern: Appleby has multiple disorderly conduct arrests in the Olympia area over the last two years.

March 2024, Lacey, out-of-town misdemeanor warrant.

February 2025, Yelm, suspicion of disorderly conduct.

November 2025, Lacey, disorderly conduct, and an out-of-town misdemeanor warrant.

Clallam County increasingly looks less like a community and more like a landing zone — a place where repeat offenders learn the system is permissive, consequences are brief, and services are plentiful. Whether Appleby stays or moves on, the pattern is the same: the county absorbs the cost, the disruption, and the risk — while officials tell residents this is “working.”

County Praise Interrupted

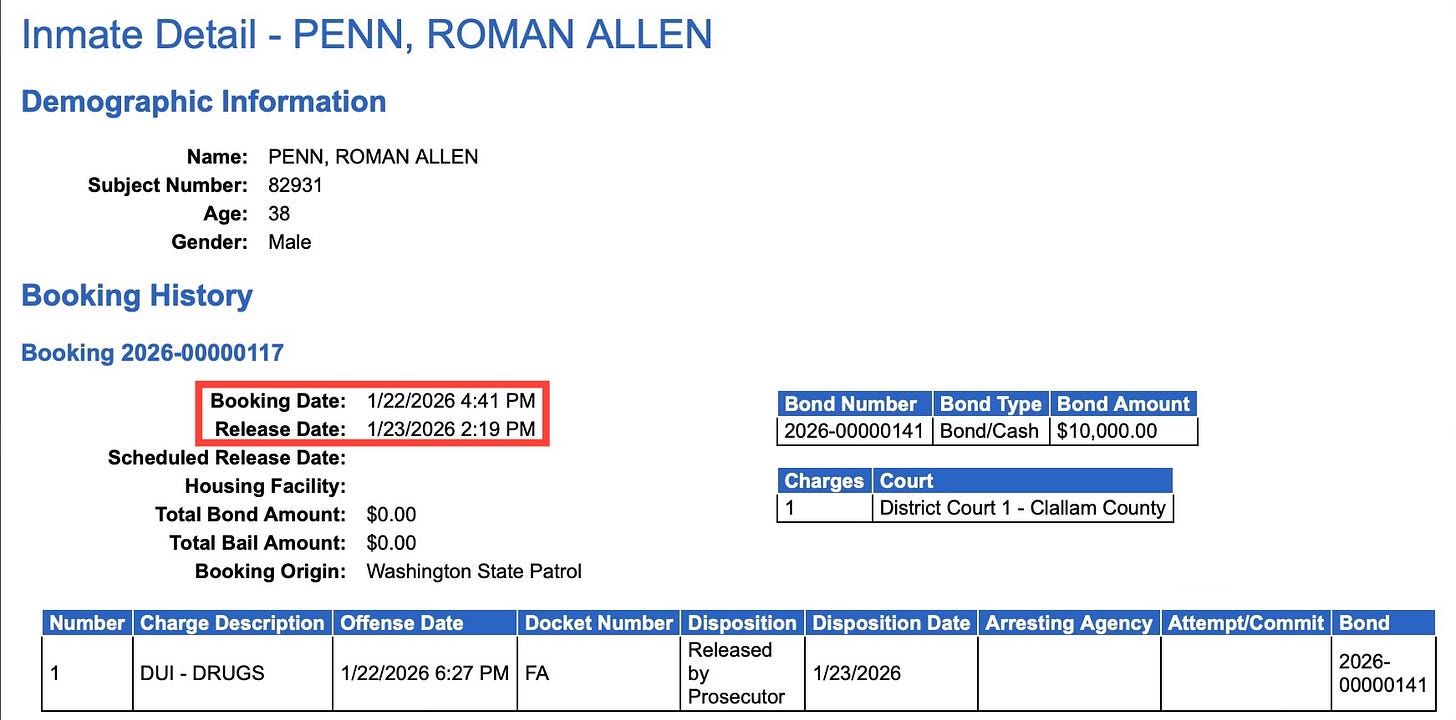

Last year, KING 5 ran a glowing report on Clallam County Jail’s Suboxone microdosing program, highlighting zero in-custody overdoses, post-release survival statistics, and a drop in the county’s overdose ranking statewide. On paper, it sounds like a model program.

But here’s the inconvenient timing: Roman Penn, featured in that very report, was arrested last week for DUI-Drugs and released the next day. Another cycle completed. Another statistic polished.

Even the report acknowledges a perverse incentive — jail staff admit some addicts are intentionally getting arrested to access treatment. That may feel compassionate, but it also exposes the absurdity of the system: jail has become a doorway, not a deterrent.

If success is defined as temporarily stabilizing people while they’re incarcerated — only to release them back into the same environment with no enforcement, no consequences, and no expectations — then yes, the program can call itself a win. But for residents living with the fallout, it feels less like recovery and more like maintenance of dysfunction.

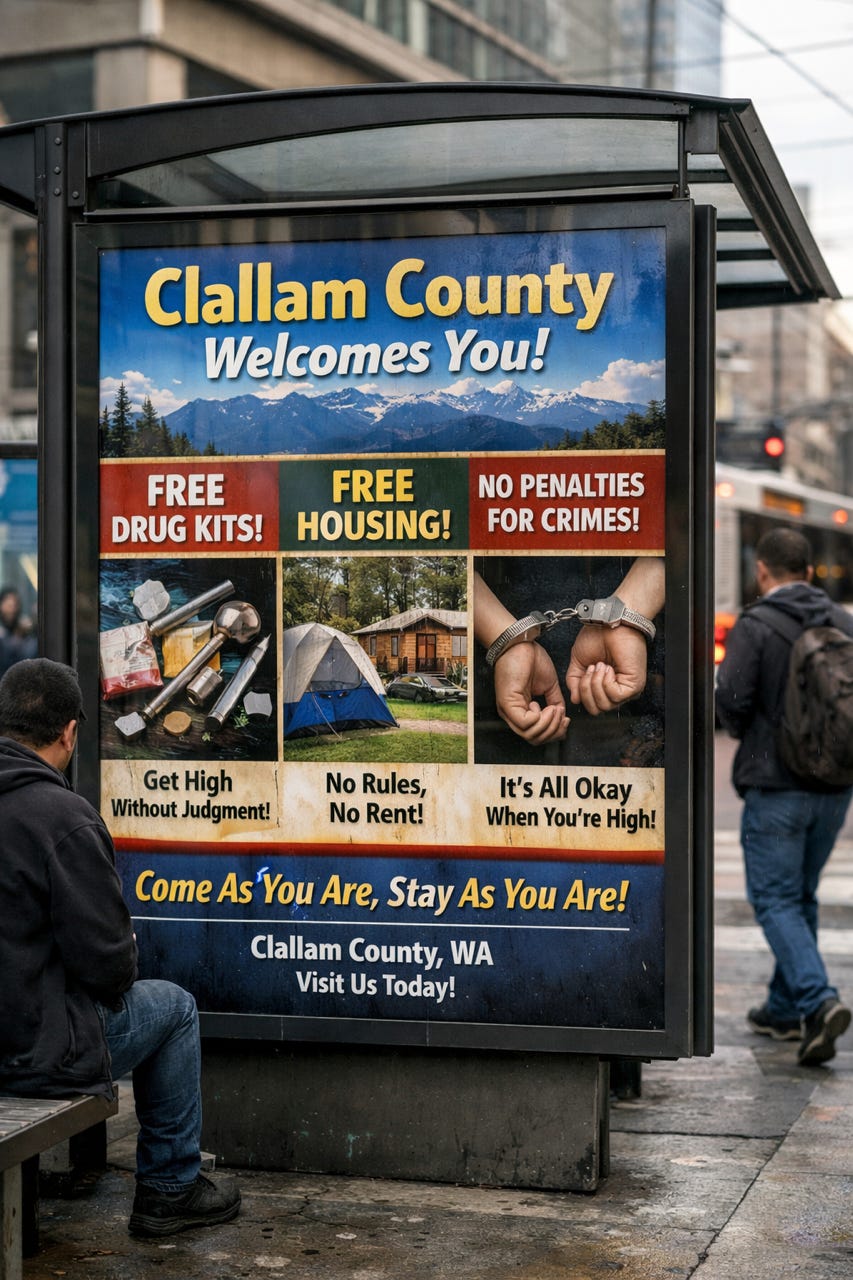

When Satire Sounds Too Familiar

If you need a break from officials insisting everything is fine, subscribe to The Strait Shooter. It’s satire — but uncomfortably close to reality.

Their recent piece announcing a fictional out-of-state marketing campaign promising free drugs, free housing, and zero consequences lands because it mirrors lived experience. Free kits, flexible timelines, accountability-free living, endless process, and advisory committees that produce reports instead of results — none of it feels exaggerated anymore.

Satire works best when it doesn’t invent absurdity — it simply rearranges facts until the truth becomes impossible to ignore. When residents can’t tell whether something is parody or policy, that’s not a failure of comedy.

That’s a failure of governance.