The $35 million Recompete grant was sold to the public as a once-in-a-generation workforce revival for the North Olympic Peninsula—a plan to rebuild timber, maritime, and natural-resource jobs. One year in, the results are hard to find. What is easy to find is the money: flowing through favored NGOs, hidden behind closed-door agreements, stripped of measurable outcomes, and championed by the same elected officials who promised transparency. At the center of it all sits Olympic Community of Health—and Commissioner Mike French.

“Hope is not a feeling, it’s action,” Clallam County Commissioner Mike French told fellow commissioners last week.

French went on to explain that hope is about goals, willpower, and pathways—lessons he said he learned at a Collective Hope dinner hosted by Olympic Community of Health (OCH). According to French, the purpose of the dinner was “to find organizations that can help organize… an internal view of hope from an organizational perspective.”

That may sound inspiring. It may even sound harmless.

But it also perfectly captures what the Recompete program has quietly become:

a philosophy exercise for NGOs—not a workforce strategy for taxpayers.

What Recompete Was Supposed to Be

The Recompete Pilot Program, run by the U.S. Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration, was pitched as a response to real economic pain.

According to official descriptions and local reporting, Recompete was meant to:

Revitalize natural-resource industries

Rebuild timber and maritime jobs

Invest in manufacturing equipment

Improve supply-chain infrastructure

Deliver accessible workforce training

Connect people to living-wage jobs

This region qualified because it is economically depressed following the collapse of logging and related industries.

That was the promise.

What Recompete Became

Instead of flowing directly into employers, apprenticeships, equipment, or trades, Recompete funds were routed through a regional lead entity.

That entity is Olympic Community of Health.

OCH is:

A 501(c)(3) nonprofit NGO

Not elected

Not created by statute

Not subject to public-records law

Not subject to open-meeting requirements

Yet OCH is now the fiscal agent, convener, administrator, and gatekeeper for a large share of Recompete funding.

In plain English: Recompete dollars flow through OCH—for a fee—before anyone else sees them.

Follow the Money: $35 Million In, $9.8 Million to OCH

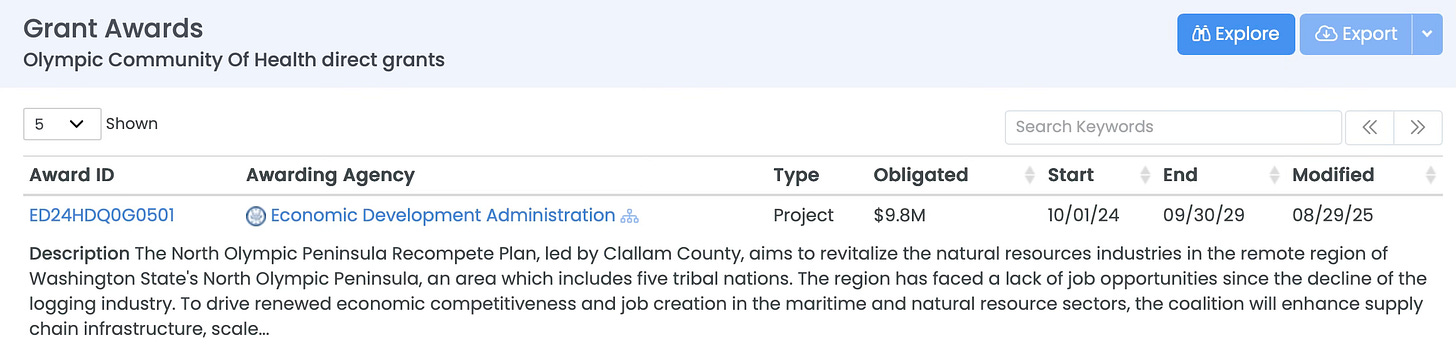

Public data confirms that OCH is not just a partner—it is a direct federal awardee.

According to HigherGov records:

OCH received $9,809,775 under grant ED24HDQ0G0501

The grant runs from October 2024 through September 2029

The money is categorized as “barrier removal,” care hubs, and coordination

Exact administrative overhead and salaries are not disclosed

The public knows how much was awarded. What the public does not know is:

How much OCH keeps

How much is paid in salaries

How many actual jobs result

What happens when targets aren’t met

OCH says it isn’t required to disclose that information—because it’s an NGO.

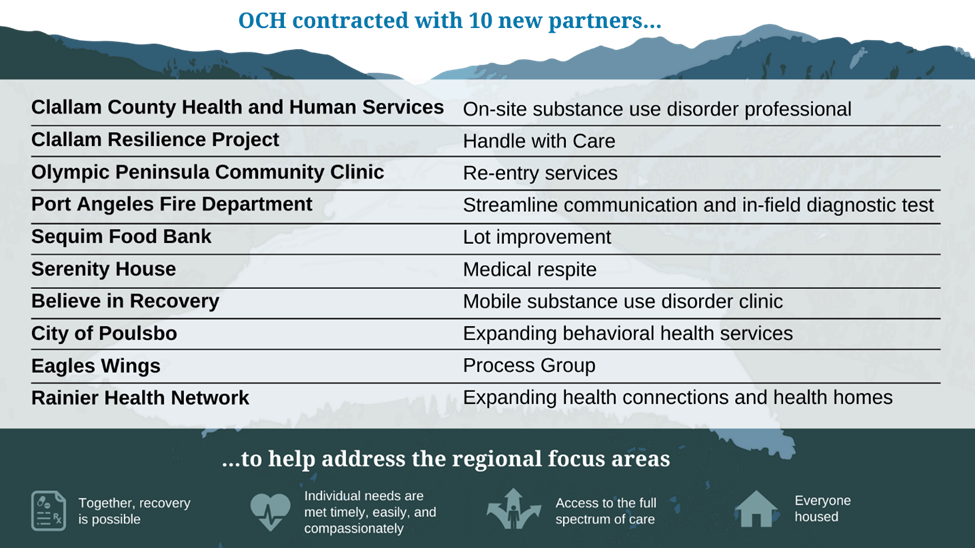

NGOs, Not Employers

Recompete money isn’t landing with mills, shipyards, or manufacturers.

It’s landing with favored NGOs.

Peninsula Behavioral Health for “training”

First Step for diapers and meals

Olympic Community of Health for coordination

Olympic Connect for intake, referrals, and data tracking

This is not job creation. It is program maintenance.

Olympic Connect: The Operational Arm

OCH didn’t just receive Recompete money—it built infrastructure to absorb it.

That infrastructure is Olympic Connect, a program:

Created by OCH

Governed by OCH

Funded by OCH-controlled streams

Used to route people into OCH-aligned services

Olympic Connect screens individuals, refers them to services, tracks engagement, and reports data upstream.

It is described as a “no wrong door” system.

But there is also no public door:

No open meetings

No public records

No voter oversight

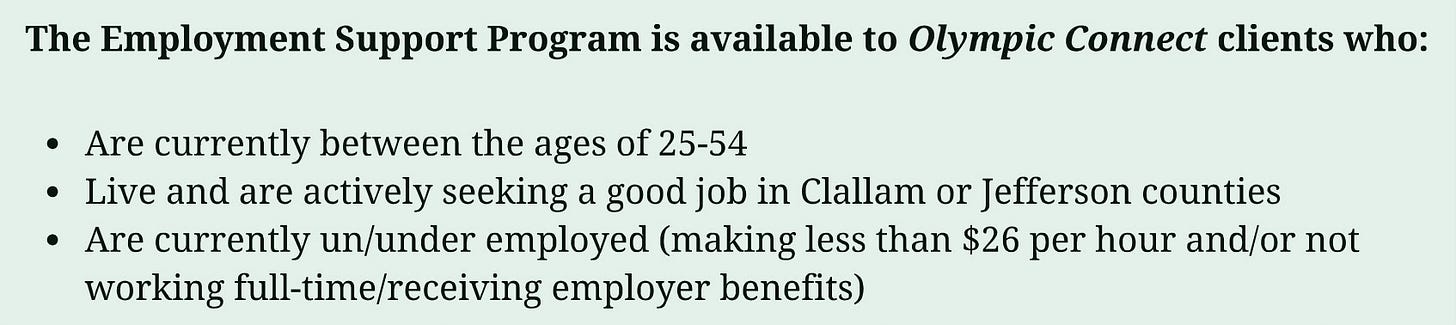

And according to program materials, some worker-retraining efforts include age caps (under 54), raising questions about age discrimination—especially troubling in a region where many older workers must stay employed.

Tribal Partnerships—or Asymmetric Power?

OCH is an Accountable Community of Health, a structure intentionally designed to embed tribal governments as governing partners.

That means tribes are not just consulted—they help set priorities and shape funding.

This has consequences:

Tribes are sovereign governments

They are not accountable to county voters

They can be service providers and decision-makers

Tribal clinics receive higher Medicaid reimbursement rates

Jamestown Family Health Clinic head Brent Simkosky serves on OCH’s Board of Directors as treasurer.

When Commissioner French was applying for Recompete funding, he openly discussed using the awarded grant funds so tribes could hire and train grant writers.

At the top of OCH’s home page, a land acknowledgement states:

Together, we acknowledge, with humility, the indigenous peoples whose presence permeates the waterways, shorelines, valleys, and mountains of the Olympic region. The land where we are is the territory of the Coast Salish Peoples, in particular the Chimacum, Hoh, Makah, S’Klallam, Suquamish, and Quileute tribes on whose sacred land we live, work, and play. Click here to learn more about the Indigenous land where you are.

DEI, Harm Reduction, and the Pandemic Blueprint

OCH did not emerge in a vacuum.

It expanded rapidly during the pandemic era, alongside:

Medicaid transformation

Harm-reduction policy

Housing-first models

Equity-based funding frameworks

OCH is also self-certified as a “woman owned business.”

OCH hosts equity convenings, promotes “lived experience” staffing, and aligns closely with harm-reduction philosophy—measuring success by engagement, not exits.

That may be appropriate for public health. But it’s a poor substitute for economic recovery.

Where Are the Metrics?

According to a KONP article, one year in, Recompete is already behind schedule.

What’s missing:

Job counts

Wage benchmarks

Employer placements

Industry expansion data

Graduation metrics

Cost-per-job analysis

What’s present:

Dinners

Newsletters

Hope language

NGO contracts

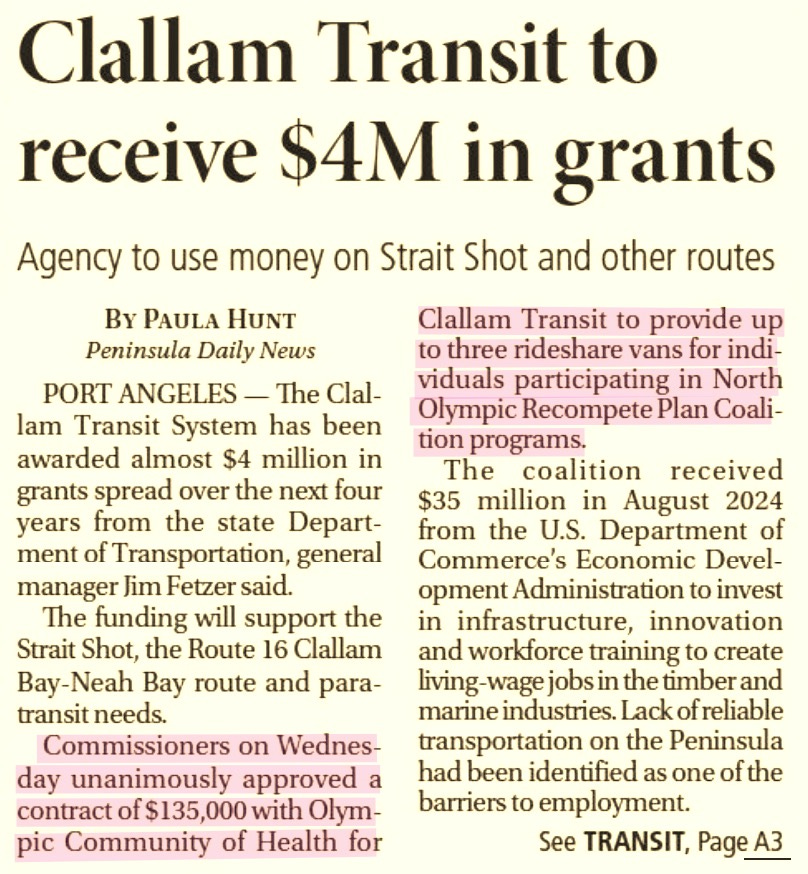

Rideshare vans justified as “barrier removal”

Once again, the commissioners are using inputs instead of outcomes to calculate metrics. This is not what the public was promised.

Mike French’s Fingerprints

Commissioner French championed Recompete.

He celebrated it publicly.

He promoted optimism on Facebook.

He now praises “hope” learned at NGO dinners.

But when asked for transparency, the answer is always the same:

It’s not the county.

It’s an NGO.

The records aren’t public.

That’s not leadership. That’s outsourcing accountability and taking credit.

The Bigger Question

Recompete was supposed to lift a struggling region.

Instead, it appears to be:

A funding pipeline for connected nonprofits

A shield against public scrutiny

A jobs program for administrators, not workers

Another pandemic-era consolidation of power

Hope may not be a feeling. But accountability is an obligation.

And right now, Recompete looks less like economic revival—and more like a slush fund hidden behind NGO doors.