A resort proposal a few miles from local homes is being marketed as a dreamy “retreat,” but West End resident Heather Cantua’s research suggests something far more calculated: a scalable short-term-rental “empire” model, prefabricated cabins tied to overseas manufacturing, aggressive monetization tactics, and a permit narrative riddled with contradictions that—she argues—shows little local knowledge of the Sol Duc Valley. The biggest story here may be bigger than one project: engaged citizens are doing the homework, educating county staff and elected officials, and changing outcomes. The county is coming alive.

This article exists because a citizen did the work

Before getting into the details, credit is due: this reporting was made possible by West End resident Heather Cantua, who did what more people are starting to do in Clallam County—slow down, research, read the documents, cross-check claims, and put receipts in front of decision-makers.

Heather attended a presentation about the planned “Luminary Resorts” development near Grouse Glen Way, left with questions, and did not accept vague reassurances as an answer. She compiled publicly available material, used transcription tools to translate non-English marketing content, reviewed the Conditional Use Permit (CUP), and then formally documented her concerns to the Board of Commissioners—followed by additional, detailed critique of inconsistencies she found in the permit narrative and supporting materials.

This is the county’s “new normal” when it’s healthy: residents showing up informed—and government having to respond.

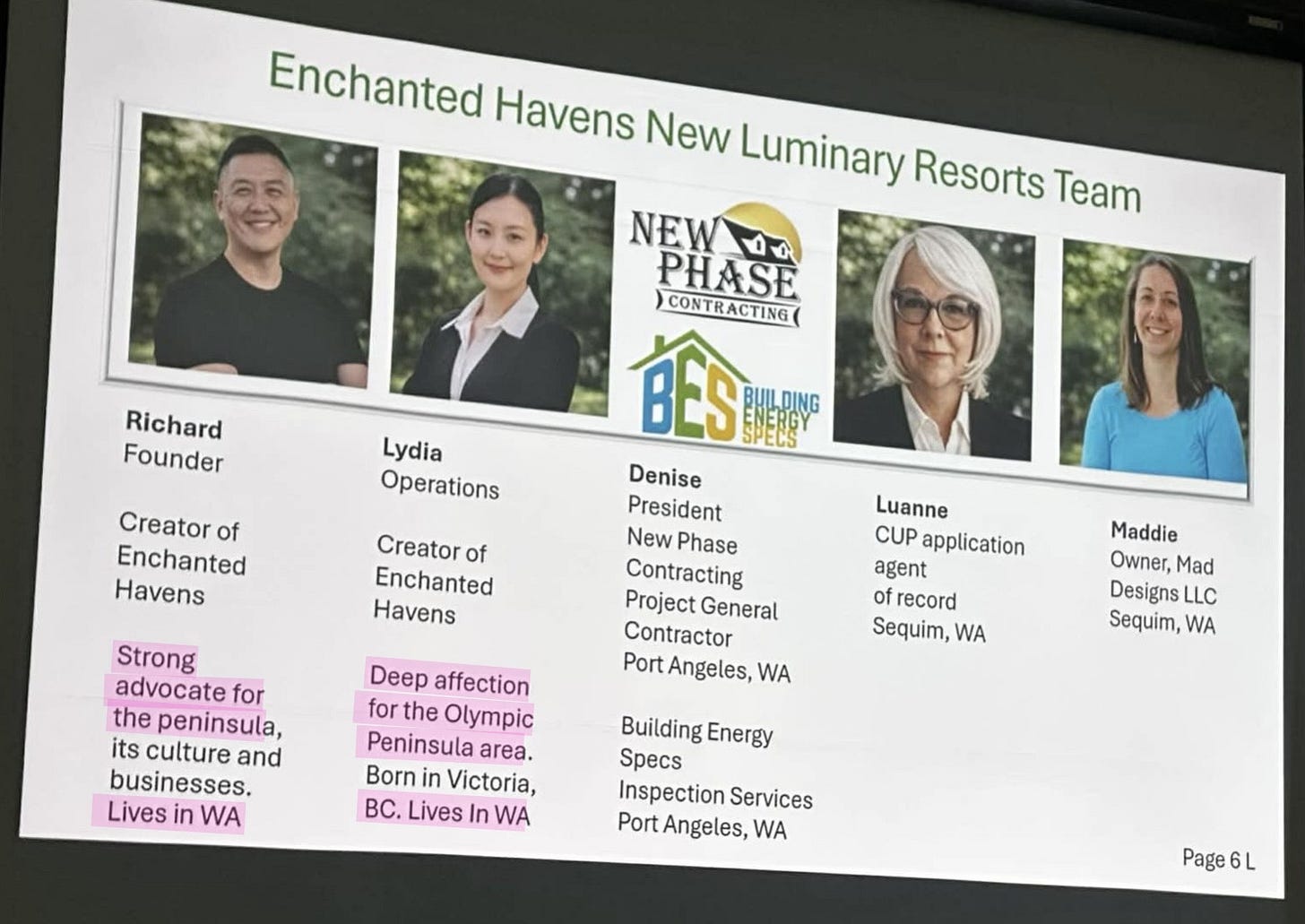

The pitch: “local,” “advocacy,” and a feel-good story

According to Heather’s summary of the West End Business and Professional Association (WEBPA) presentation, the project was introduced with a familiar script: founders framed as people who “love the peninsula,” a resort marketed as a restorative experience for couples, and a promise that the development will support local culture and business.

But when Heather pressed for specific examples of local advocacy, none were provided. More importantly, she reports being told the ownership structure involves a pool of investors with properties across the United States, including Olympic Peninsula homes converted into short-term rentals, plus an existing mirrored-cabin property in Texas presented as a model.

That’s when the right question surfaced: Is the Sol Duc Valley the point—or just another dot on a national business map?

A different story appears online: scaling, manufacturing, and “tokenization”

Heather’s research points to a broader business plan described on the “Luminary Resorts” YouTube channel (in Chinese-language videos).

In the videos, the founder allegedly describes a step-by-step strategy:

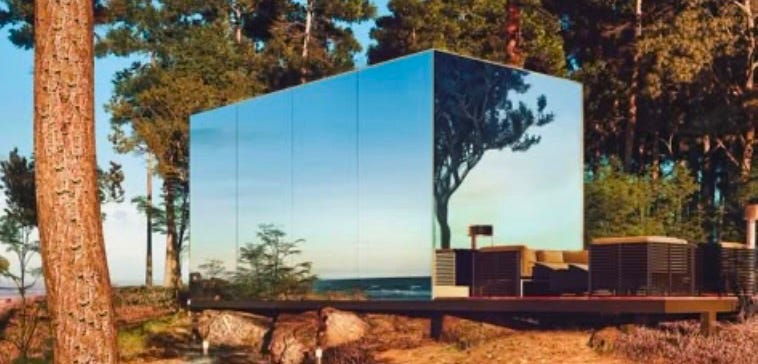

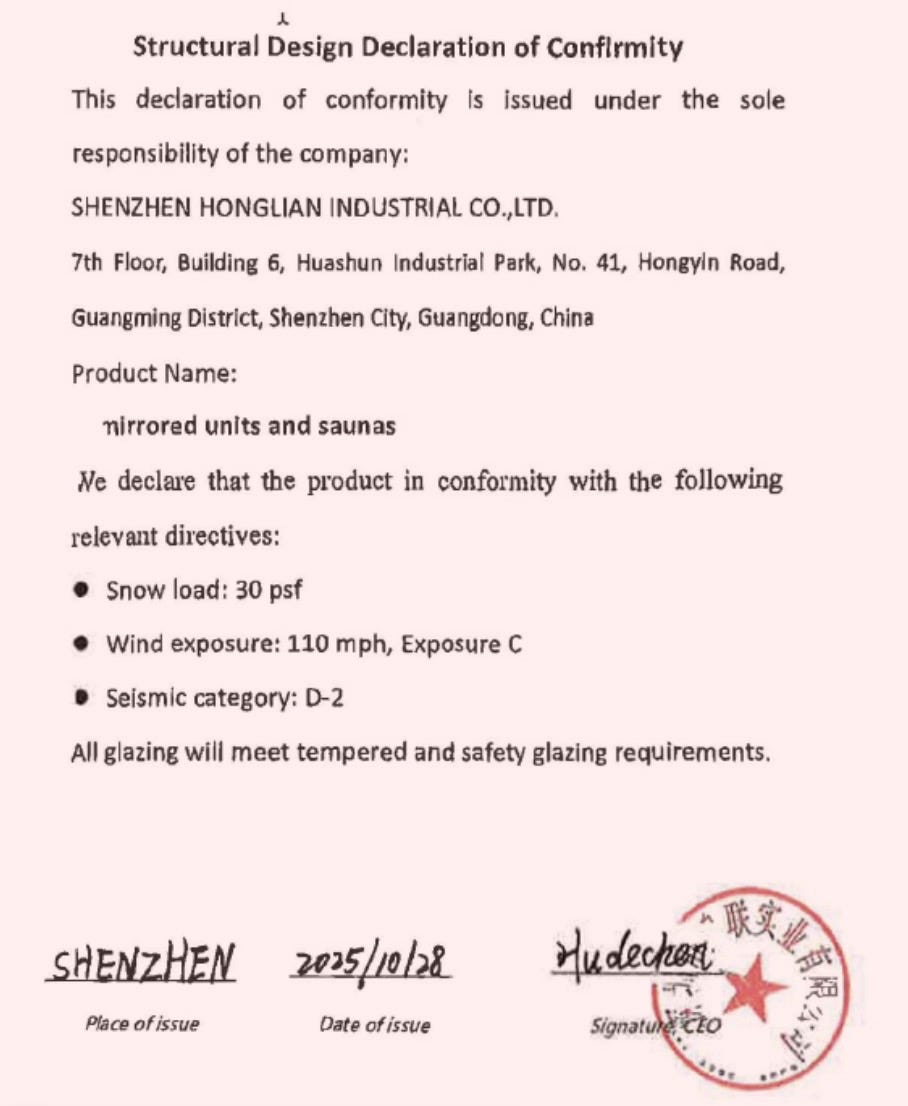

Manufacture mirrored cabins in China

Acquire land in the U.S. to place them

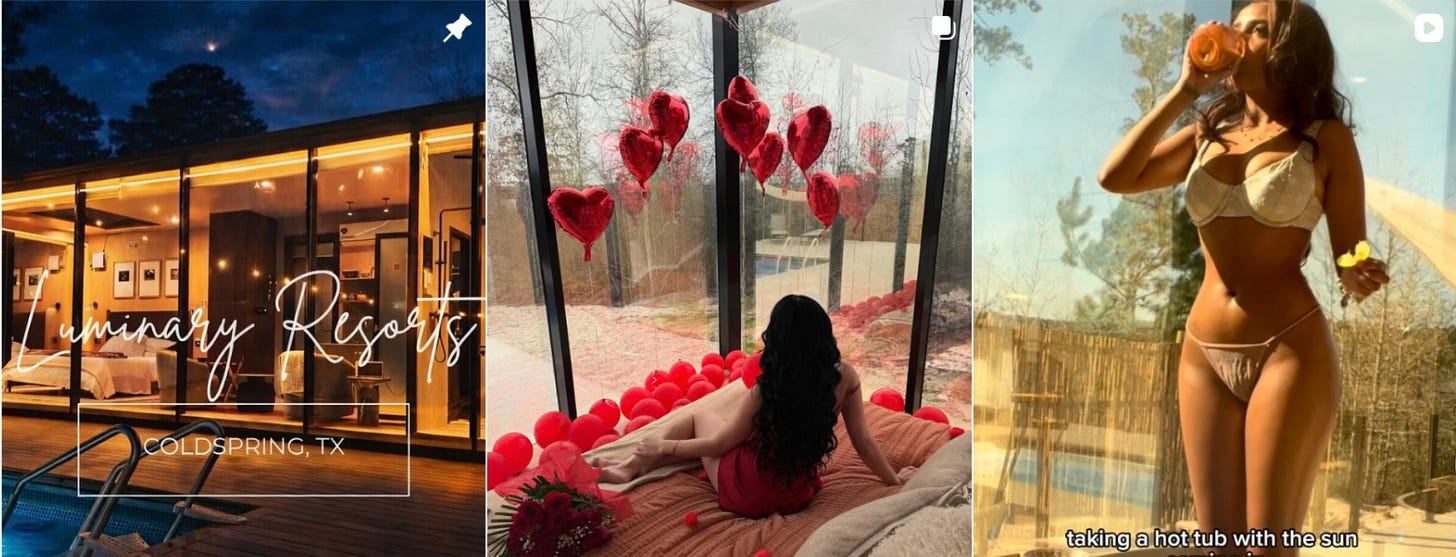

Operate them as short-term rentals with heavy Instagram-style marketing

Then “tokenize” ownership—selling small fractional interests to followers/investors through a company called PropTory

If accurate, that’s not a locally rooted hospitality project. That’s a replicable investment product.

And that matters because Clallam County’s land-use decisions are supposed to be grounded in things like compatibility with surrounding character, infrastructure realities, and environmental constraints—not just how good a cabin looks in influencer photos.

The “cash cow” mindset—and what it signals

Heather highlights marketing material describing a Lake Sutherland short-term-rental property as a high-performing revenue machine—portrayed as a model of profitability and pricing strategy.

Translation of YouTube video description:

In July 2024, during the peak tourist season around Seattle, “Blue Haven” experienced its moment of glory, achieving a gross monthly income of $47,000—a figure almost equivalent to the property’s entire annual income in previous years.

This achievement was thanks to Richard’s accurate understanding of market demand and flexible pricing strategy. The high income during the peak season easily covered the annual bank loan (approximately $4,500 per month), and the combined income from July and August alone was sufficient to repay the entire year’s loan and operating expenses, leaving the remaining 10 months almost entirely as profit.

This balanced income between peak and off-peak seasons ensured stable profitability throughout the year, making the property a true “cash cow” in the short-term rental market.

She also flags content she interprets as a troubling tone: discussions of serious incidents framed primarily through revenue impact, paired with messaging about “protecting assets.”

Whether one finds that morally jarring or simply revealing, the bigger point is practical: it communicates priorities—and those priorities don’t sound like “community partnership.” They sound like optimization.

The permit problems: contradictions, basic errors, and what looks like “AI filler”

In her follow-up to commissioners, Heather argues the Conditional Use Permit contains material inaccuracies and inconsistencies that should be disqualifying on their own—among them:

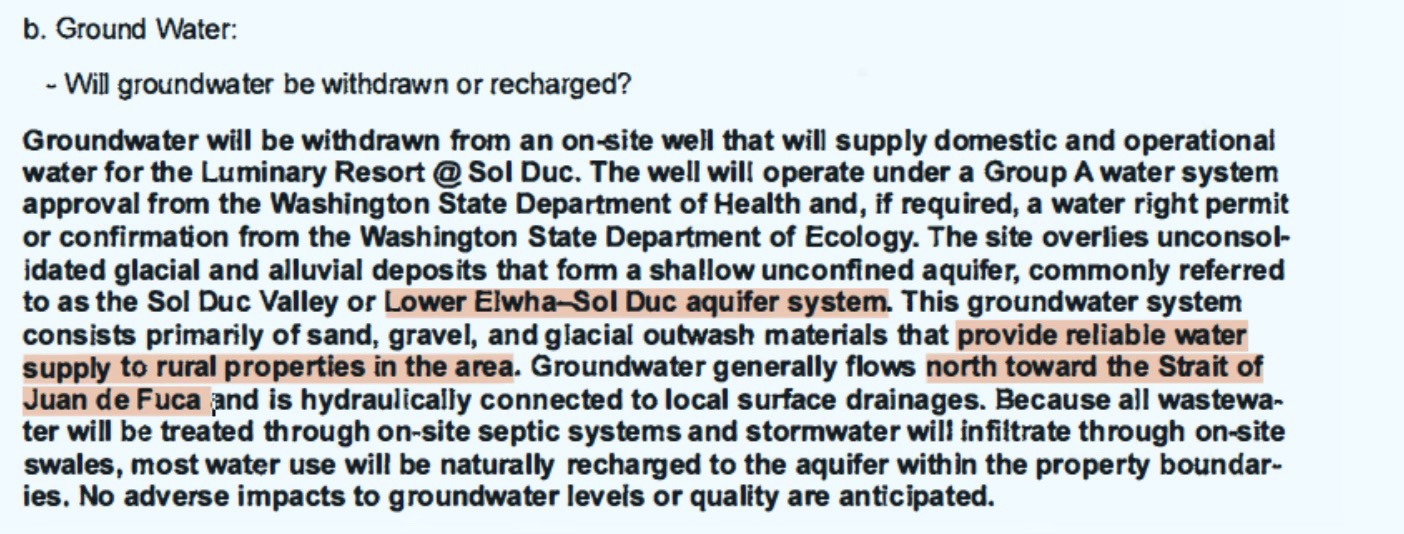

Watershed and hydrology claims that don’t match reality

She asserts the CUP invents or conflates watershed/aquifer language and misstates basic geography of the Elwha and Sol Duc systems—errors that a local author should not make.

A “reliable water supply” claim that clashes with lived reality

She points out that the Sol Duc Valley’s water reality is self-reliance, conservation, and seasonal well vulnerability—conditions that may be survivable for single-family homes but risky for a resort-scale occupancy scenario.

Wildlife compatibility concerns

Heather describes extensive elk presence and argues dense, frequent human use on the property is fundamentally incompatible with that pattern—especially if the “solution” is fencing that doesn’t actually resolve the conflict.

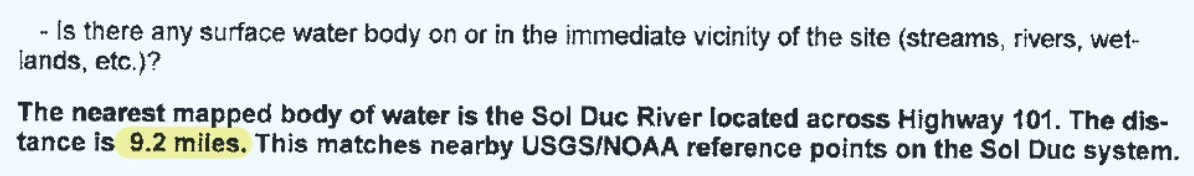

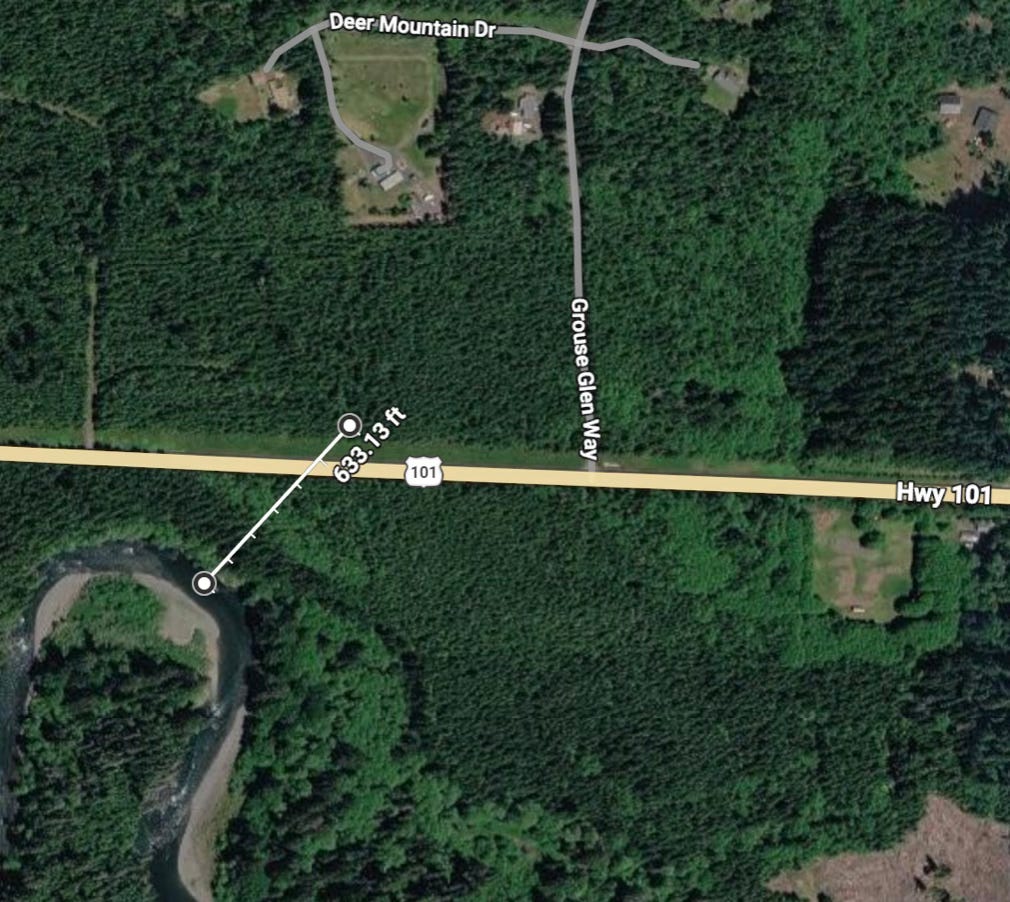

Distance-to-river statements that appear wildly off

She flags a claim that the Sol Duc River is nine miles away, while mapping tools suggest it is far closer to the proposed infrastructure area.

Invasive species omission

Heather criticizes the CUP for failing to address Scotch broom—its wildfire risk, persistence, and long-term seed bank.

Unreadable tables and pixilated “key information”

She notes that portions of the CUP appear too degraded to verify key details—plants, materials, appliances, utilities, lighting, and other specifications.

Power outage reality ignored

She argues that an all-electric guest experience, with no clear outage plan, invites predictable failure in a valley known for outages—contrasting it with the West End’s traditional self-sufficiency (wood heat, stored supplies, backup planning).

A dark-sky valley treated like an afterthought

Heather’s most powerful section is personal: the Sol Duc Valley as a dark sanctuary—no streetlights, no freeway glow, no visible electric lights—where natural rhythms and wildlife are part of daily life. She then contrasts that with a plan she says includes dozens of light posts and language asserting “minimal” impact, plus contradictions between what was said publicly and what the CUP states.

AI optics: “community engagement” illustrated with an AI-looking image

Heather argues the presentation itself undermined credibility—using imagery that looks AI-generated to depict “neighbors,” while (in her view) demonstrating a lack of real, sustained West End engagement.

One of Luanne’s slides at WEBPA focused on community engagement. It featured an image of two people leaning against a wooden fence, as if they were neighbors. The image had soft edges, surreal details, and cartoonish pixelation, all hallmarks of an AI generated image.

It struck me as hilarious that Luanne used an AI photo to demonstrate her “community engagement”. She couldn’t post a real photo of community engagement because she hasn’t done any real engagement.

You don’t have to share every conclusion Heather draws to recognize the core issue: a Conditional Use Permit is not supposed to be a vibes document. It’s supposed to be accurate, verifiable, and locally literate—because it’s the foundation for a land-use decision that neighbors live with.

“Engagement” isn’t a mailer and a mandatory hearing

Heather also makes a point worth underlining: mailing notice to immediate neighbors may satisfy the legal requirement, but it isn’t community engagement—not when “participation” means West End residents have to drive an hour-plus each way on a weekday afternoon, reshuffle work and family schedules, and compete for a few minutes at the microphone only after the application is already in motion.

The West End has its own civic ecosystem—WEBPA, the Chamber of Commerce, a local newspaper, an independent radio station, and informal networks. Heather argues that if proponents can produce dozens of marketing videos and investor-facing presentations, they can also show up consistently, early, and transparently in the actual community they’re changing.

A quick reminder about Luanne Hinkle’s public track record

As readers will recall, Luanne Hinkle previously served as Executive Director of the Olympic Peninsula Humane Society during a period that ultimately ended in severe financial distress and the temporary shutdown of the Bark House campus—an outcome that had real downstream consequences, including disruptions to county animal control operations. Notably, Hinkle received a 48% increase in compensation in the period leading up to the organization’s financial collapse, a fact that continues to raise questions about oversight, priorities, and fiscal stewardship.

Whatever one thinks of that episode, it’s relevant context for residents evaluating credibility when they’re asked to trust rosy projections, vague assurances, and deflected basic questions about operations and risk.

The real headline might be this: Clallam County is waking up

Whether the Hearings Examiner denies the CUP, conditions it heavily, or sends it back for correction, the civic shift is already happening.

A West End resident did the research.

She documented inconsistencies in the public record.

She educated officials with specifics—geography, utilities, wildlife, dark-sky impacts, invasive species, and basic permitting quality control.

And now the project isn’t just a slideshow. It’s a public test: can Clallam County enforce standards, verify claims, and protect community character—especially in rural places where the margin for error is small?

This is what it looks like when residents stop being passive recipients of decisions and start being co-authors of outcomes.