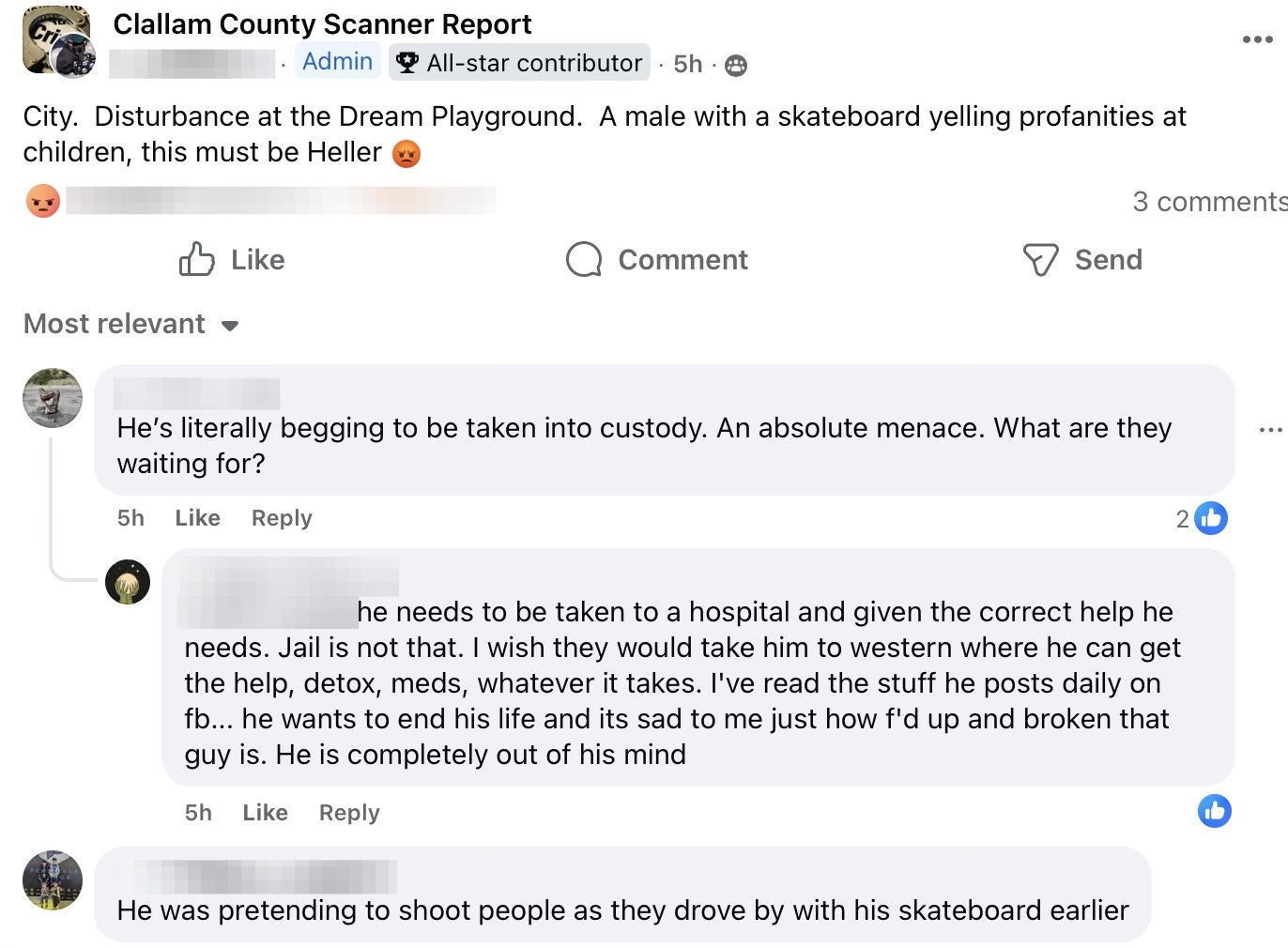

For five years, Clallam County resident Michael Heller has been a constant presence on the police scanner—disturbances, arsons, assaults, and public meltdowns. His behavior has become a fixture in community chatter, a source of fear for families, and a drain on public safety resources. With dozens of local nonprofits and behavioral health programs claiming to provide help, one has to ask: what does it actually take to get help in Clallam County—and what will it take before someone is hurt?

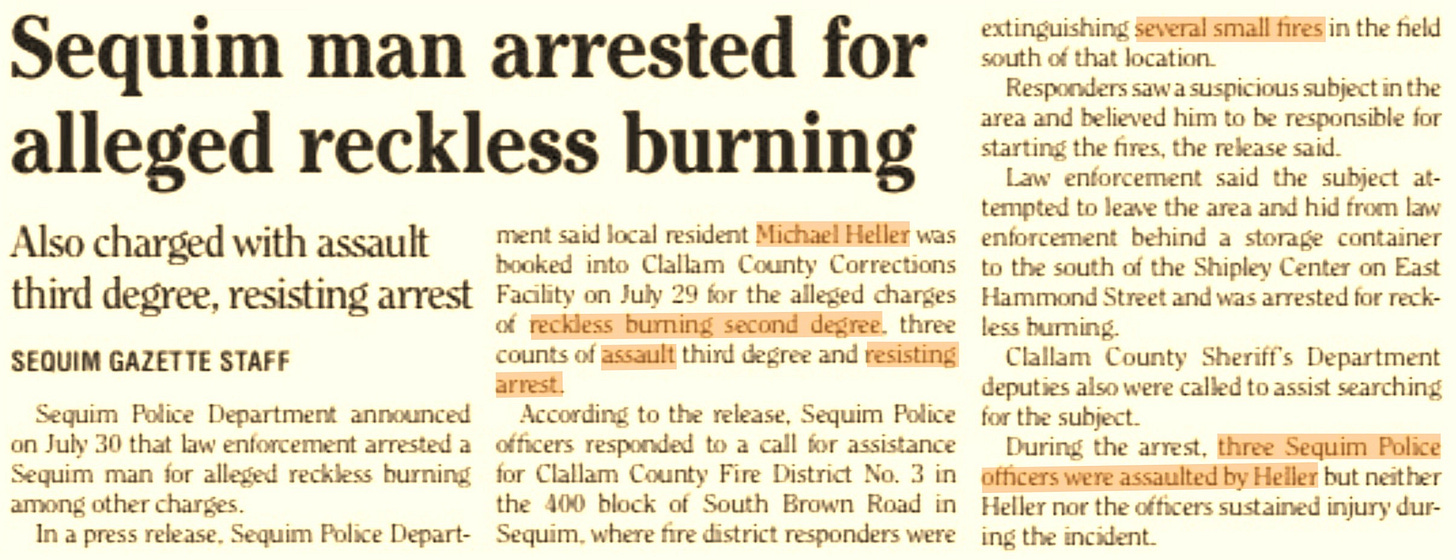

It’s been more than five years since Michael Heller first appeared in the local news for allegedly setting fires in Sequim and assaulting police officers. At the time, a judge ordered a competency evaluation. Since then, Heller’s name has surfaced repeatedly—on the police scanner, in Facebook community alerts, and in countless reports of disturbances across Port Angeles and Sequim.

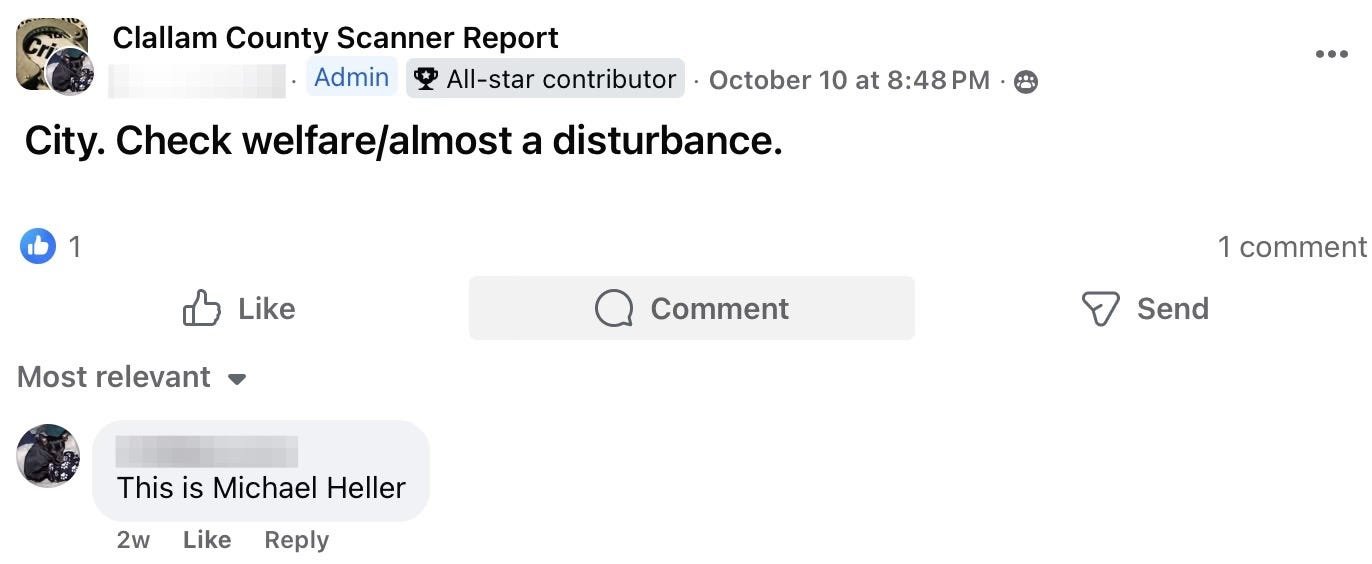

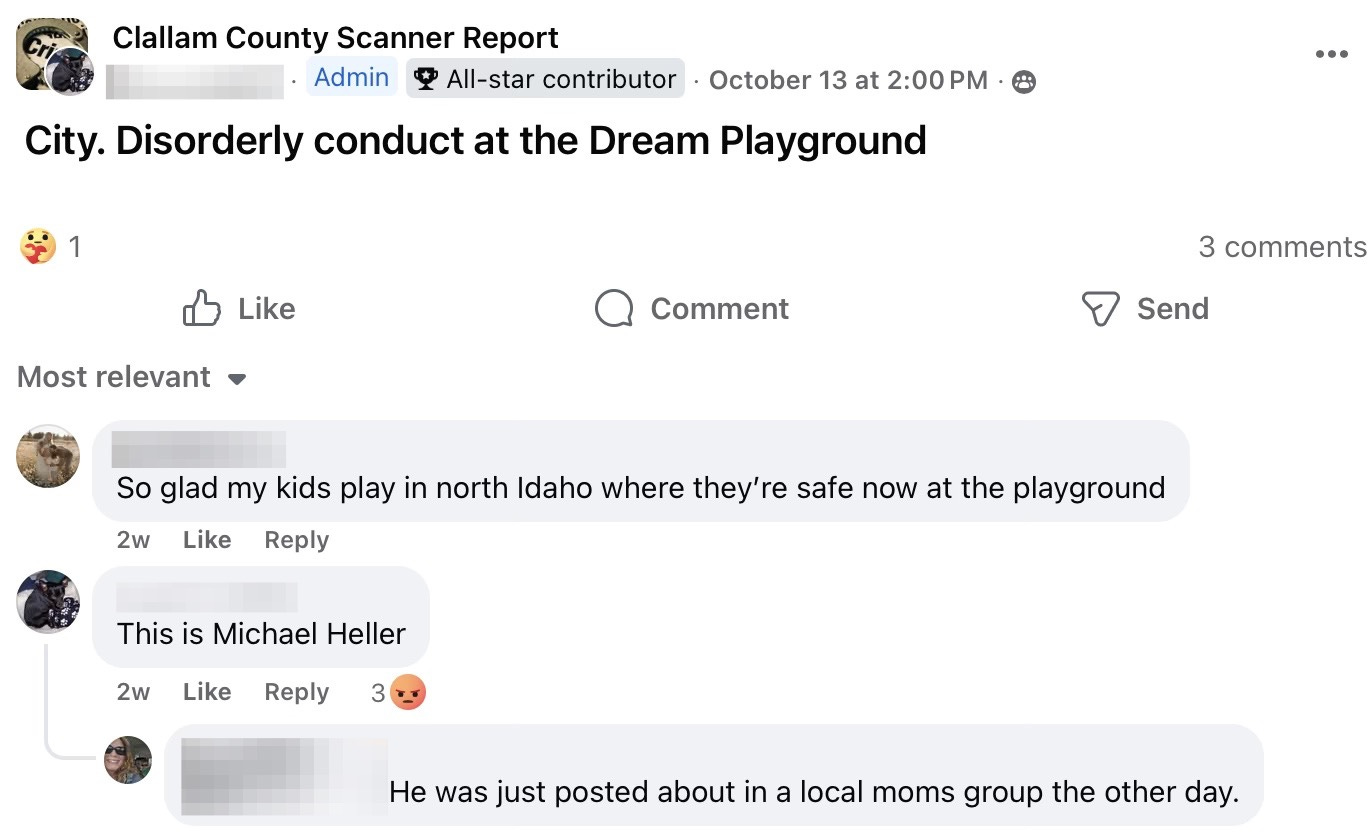

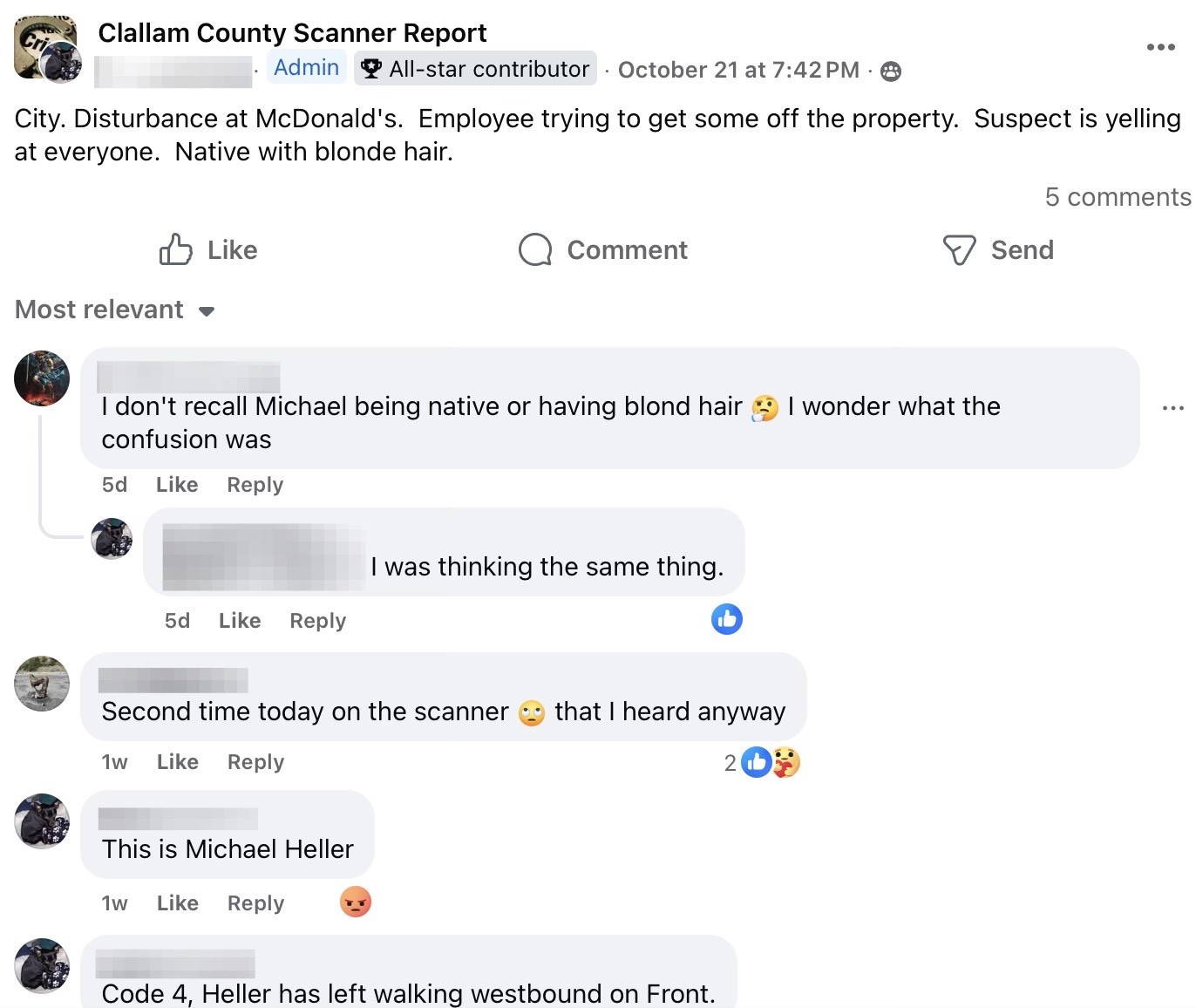

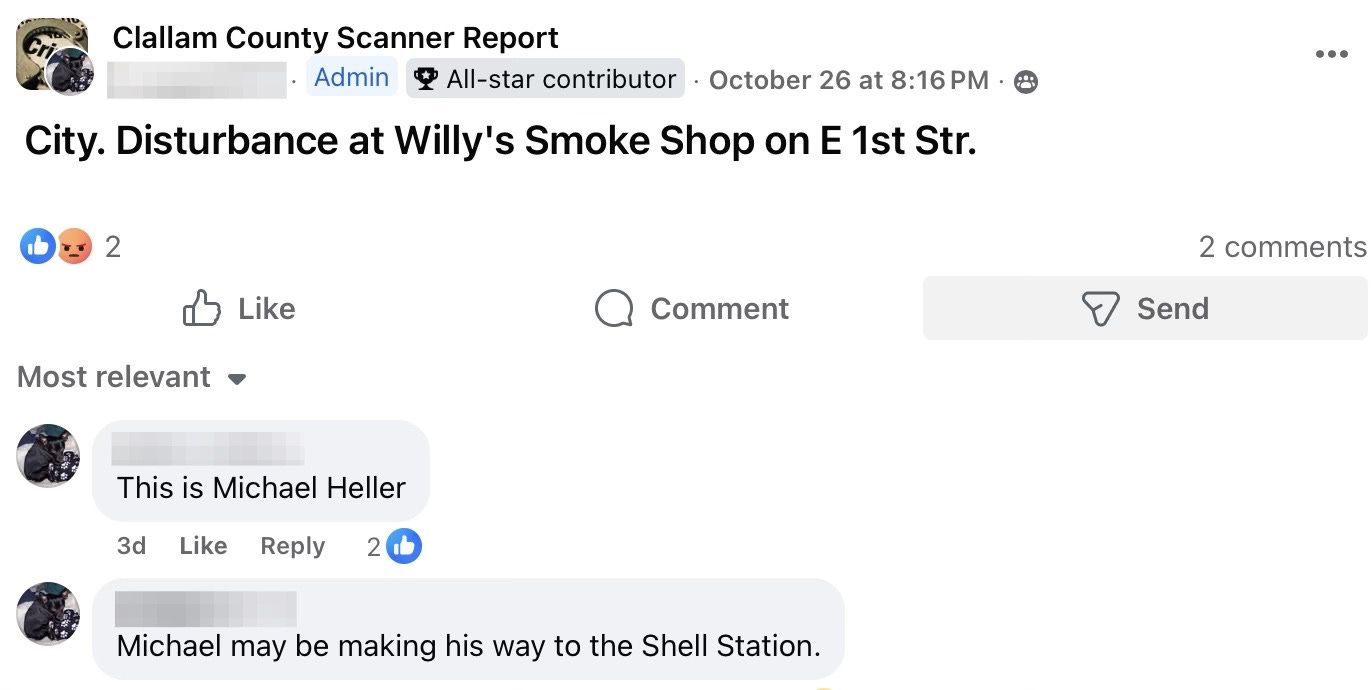

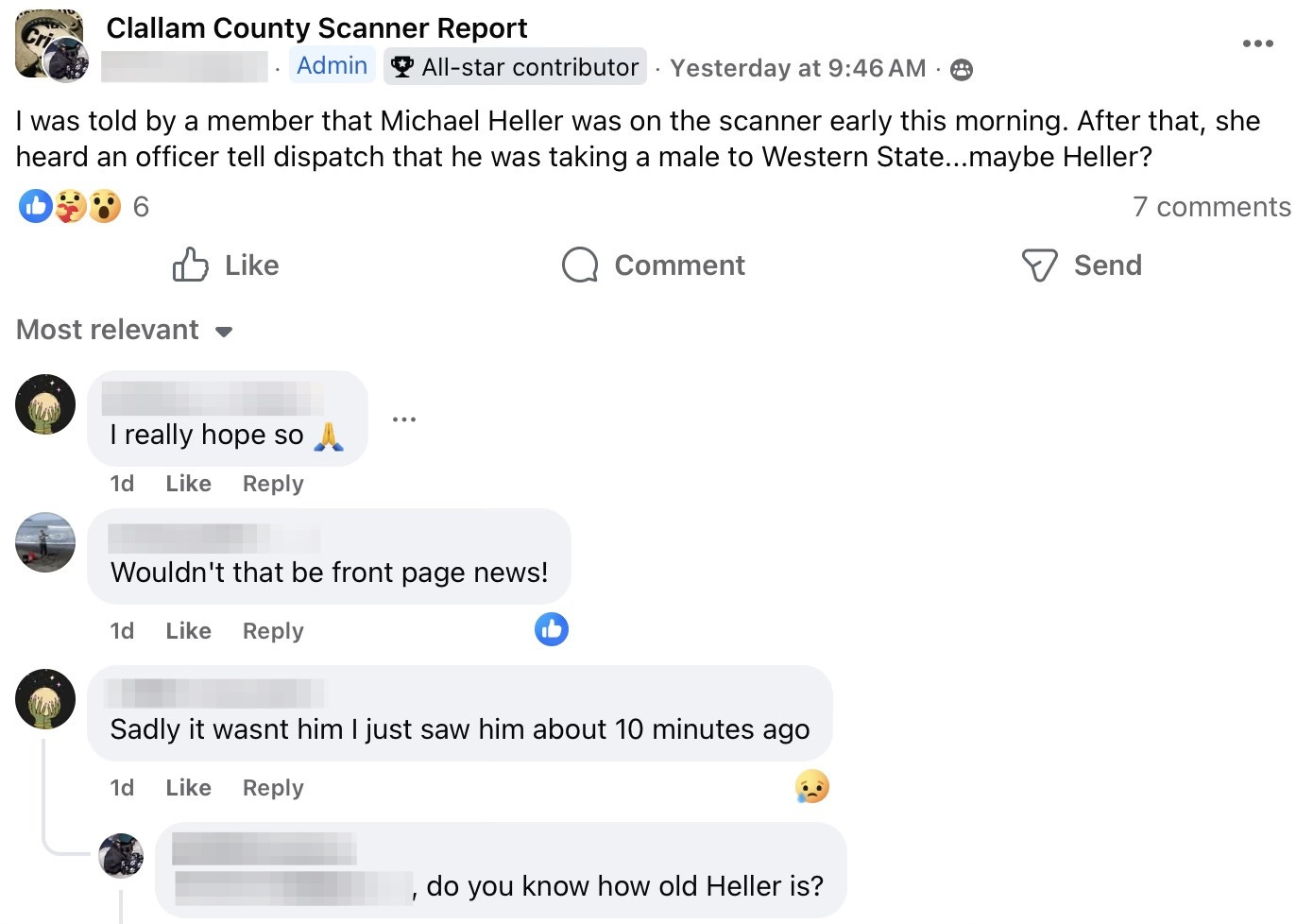

Despite a long and violent history of unpredictable behavior, Heller remains at large, moving freely between parks, playgrounds, and public spaces. Residents routinely encounter him shouting at strangers, running into traffic, or starting disturbances in businesses. Each call ends the same way: law enforcement responds, emergency services are dispatched, and after a brief intervention, he’s back on the streets—often within hours.

This is not an isolated case. It’s a symptom of a broken system. Clallam County has more behavioral health programs, task forces, and nonprofit “partners” than ever before. The county touts progress, holds summits, and awards grants. Yet the evidence on the ground tells a different story—one man has been allowed to terrorize an entire community for half a decade, unchecked and untreated.

Families no longer feel safe using parks like Dream Playground. Local businesses have stopped calling the police because they know it won’t matter. And residents wonder: why is this tolerated?

In 2018, Heller was charged with multiple counts of reckless burning and assaulting officers after allegedly setting fires near Sequim’s Olympic Discovery Trail and near South Brown Road. He was ordered to undergo a competency evaluation. Seven years later, he’s still cycling through the same pattern—disturbance, arrest, release, repeat.

This is not compassion. It’s neglect—both of the public and of the individual who clearly needs intervention. Clallam County leaders claim to be addressing mental health, but if this is the result, then something is deeply wrong.

How will this end? In a fire? A fatal encounter? A tragedy that everyone saw coming but no one acted to prevent?

Doctors, professionals, and families are leaving our area—not because our schools are outdated, but because lawlessness and dysfunction are being normalized. Public safety, once a core government service, has become secondary to poetry readings, luxury homeless housing, and bureaucratic posturing. Until local leadership and the network of NGOs confront the reality of failure, the next tragedy is only a matter of time.

This is a five-year timeline of scanner calls, Facebook reports, and firsthand accounts that show the shocking continuity of one man’s reign of chaos—and how local officials continue to look the other way.