What do boofing kits, broken tractors, and free meth pipes have in common? In Clallam County, they’re all taxpayer-funded. Dive into a local economy fueled by grant grifting, public spending with no receipts, and “harm reduction” that forgets the harm. From rigged school bond campaigns to fire-prone homeless encampments, the people paying the price are the ones playing by the rules.

When policy enables crime: A boofing kit economy

In Clallam County, “harm reduction” means giving out free meth pipes, fentanyl test strips, and even “boofing kits”—tools to help people ingest drugs rectally. But when addiction is subsidized and employment is secondary, theft becomes the stopgap. Local businesses are left with busted windows, stolen goods, and rising insurance rates. The cost? Passed on to you.

You pay more at the register. You pay more in taxes. You pay for the pizza handed out at the harm reduction center to an addict who just made sure you pay a little more to live in an economically depressed county.

RECOMPETE and the new grant economy

The $35 million RECOMPETE grant aims to reinvigorate the local workforce—but in Clallam County, even economic recovery is being monetized into a grant hustle. County Commissioner Mike French has floated the idea of using the funds to train tribal grant writers. Peninsula College is already in on it, offering classes like “Mission Revenue Launch Pad” to help nonprofits find ways to make unrestricted revenue from restricted funds.

Is this economic development or an elaborate circle of public dollars feeding on itself? Taxpayers fund the grants, the grant writers, and the programs built around chasing more grants.

Port Angeles: where 1,600 hours equals “end of life”

Port Angeles City Council candidate Marolee Smith Dvorak uncovered a peculiar line item in a recent Port Angeles City Council agenda: a $49,633.93 tractor replacement. The current tractor—a Kubota MX5000 from 2005—has just 1,610 hours on it. That’s less than 7 hours a month. Kubota expects 4,500–5,000 hours minimum lifespan. So why replace it?

The City says it’s “reached end of life.” No maintenance records provided. No repair breakdown. Just a vague $30,000 repair estimate—double the cost of a full engine rebuild.

Instead of fixing what we own, staff prefers buying top-shelf equipment from an out-of-county vendor, bypassing local dealers. Meanwhile, we face declining tax revenue, pleas to the state for more aid, and ever-growing fees.

This isn’t fiscal management. It’s fiscal performance art. Click here to read the full article and decide if Marolee deserves your vote.

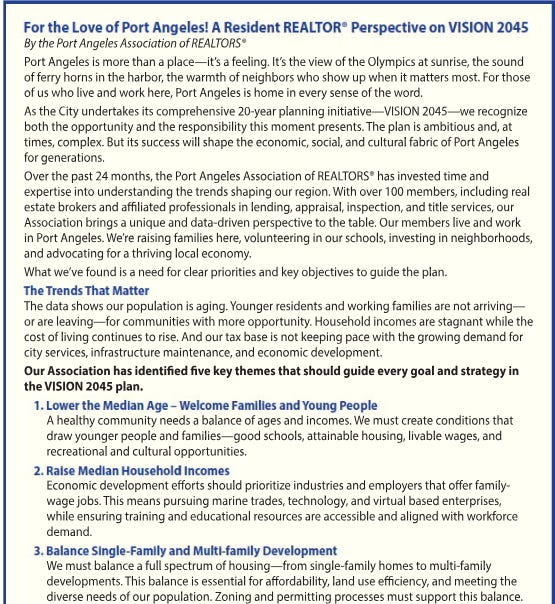

Vision 2045: noble goals, harsh realities

The Port Angeles Association of Realtors recently released “Vision 2045,” outlining hopes for a thriving, family-friendly community. But those goals clash with a reality where playgrounds are used for drug injection, city parks double as tent encampments, and public land disappears from the tax rolls as it’s absorbed by government agencies and tribal trusts.

Prosperity won’t come from taxing ourselves into oblivion. It will come from restoring function, safety, and accountability.

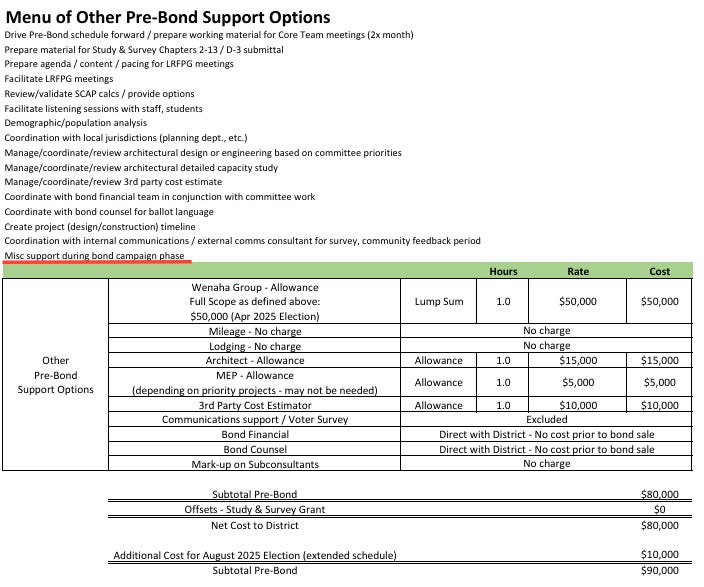

When the government campaigns on your dime

Communications between the Sequim School District and their bond consultants confirm that taxpayer money was used for “misc support during campaign bond phase.” That’s code for using public funds to sway voters—one of many tactics the district employed to pass its recent bond. Washington Policy Center states that school districts across the state are increasingly engaging in unethical and misleading practices.

Taxpayers aren’t just footing the bill for schools. They’re funding the marketing campaign to convince them it's worth it.

📖 Read more: Washington Policy Center Article

The curriculum of contrition

For years, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe and the Sequim School District have collaborated on a curriculum that highlights historical injustices committed by colonizers, and their message appears to be effective.

That truth matters. But it’s also worth noting that no culture's history is pristine.

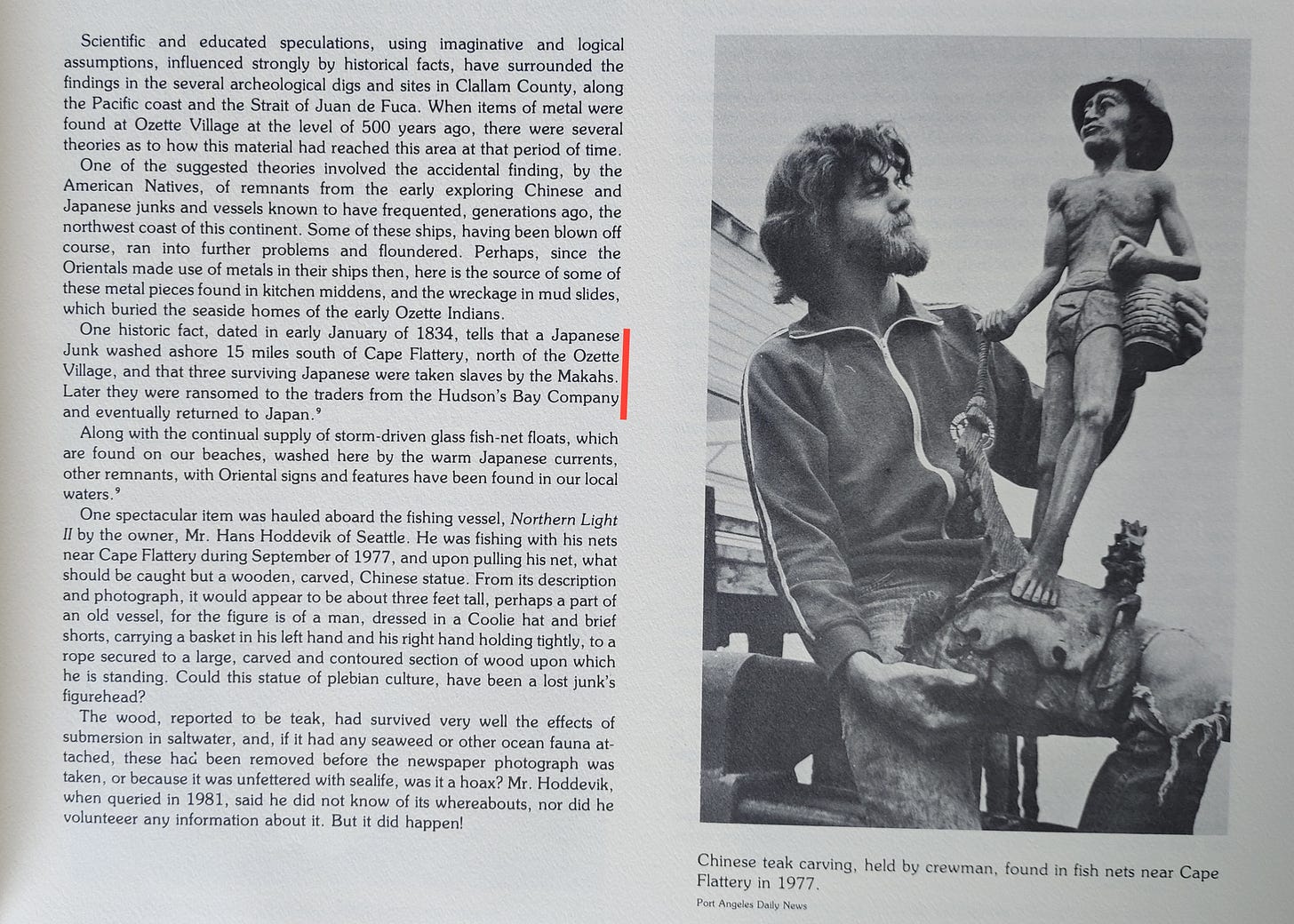

In 1834, according to local historian Harriet Fish in “Tracks, Trails, and Tales,” three Japanese sailors shipwrecked near Cape Flattery and were enslaved by the Makah before being ransomed to the Hudson's Bay Company.

History is messy. Teaching it doesn’t require sanitizing one group and demonizing another. We all need to learn, not just from history’s victims, but from its full complexity.

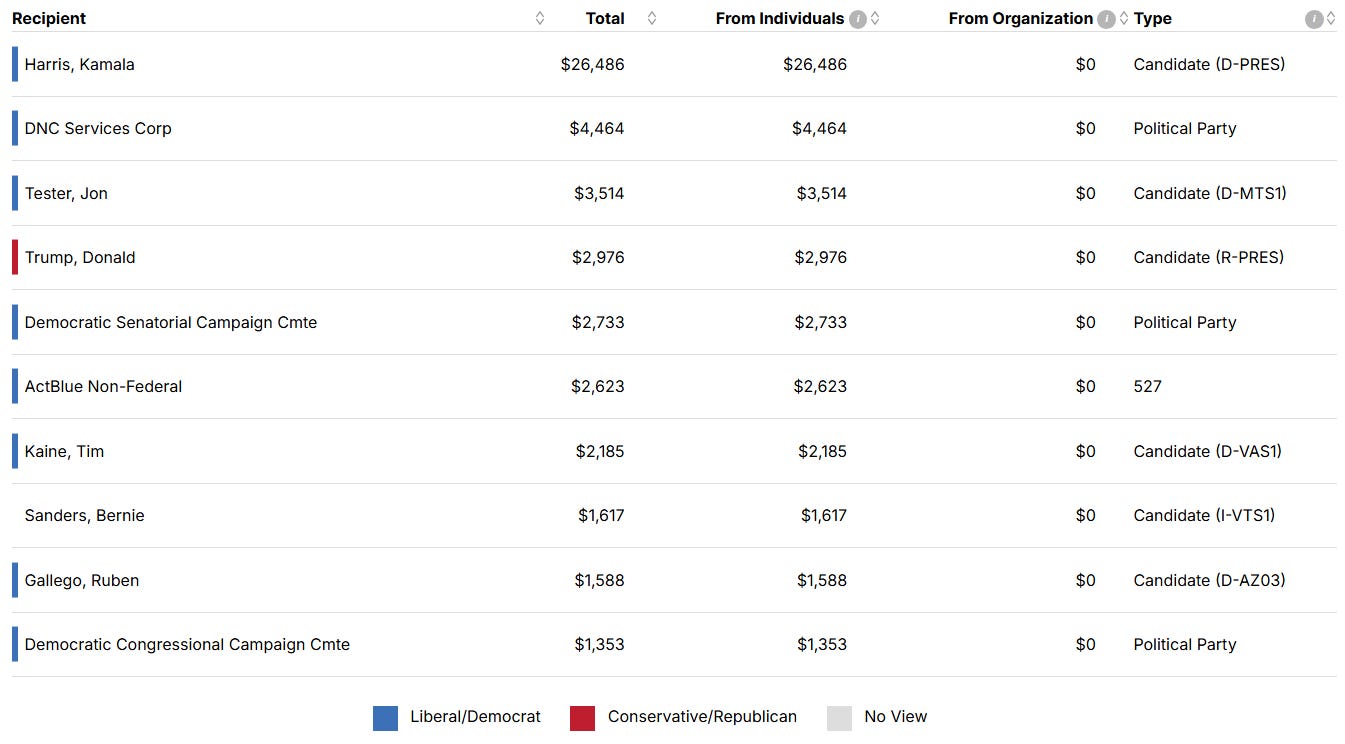

Habitat for Humanity: charity or lobbying arm?

Locally, Habitat for Humanity of Clallam County presents itself as a community-based nonprofit. But at the national level, Habitat is a political lobbying group that donates to candidates and influences federal housing policy.

Before donating, ask yourself: are you funding homes, or political campaigns?

📊 See the lobbying records here: OpenSecrets Profile

RV fires, risks, and ruin

RVs have become a last resort shelter for many in Clallam County. But their growing presence on public streets comes with steep risks. Fires are frequent, often caused by:

Overloaded electrical systems

Improper use of propane or space heaters

Candles and open flames

Flammable clutter and poor ventilation

RVs aren’t designed for permanent housing. They’re not safe, not stable, and when they’re abandoned, the cleanup falls on taxpayers. Just ask the Makah Tribe, currently facing the costly disposal of 150 abandoned vehicles, 6 RVs, and 3 mobile homes.

Code for me, but not for thee

Planning a yard sale in Sequim? The city has rules:

Items cannot be displayed in public right-of-way or on sidewalk

No signs on poles, sidewalks, or medians

Clean up your signs after

But if you’re homeless, there’s no code enforcement for tarps, shopping carts, or sidewalk obstructions. One group gets fines. The other gets free reign.

Transit hub or trouble spot?

The 100 block of West Cedar in Sequim—home to the Transit Center and a county-funded Narcan dispenser—has become a regular feature in the Sequim Gazette’s police blotter.

Incidents there rose sharply after the “free fare” program began in 2024, funded by the Climate Commitment Act, a hidden tax on gasoline.

It’s not free. You’re paying for it at the pump. And increasingly, you’re paying for it in public safety.

Burlington, Vermont: a mirror image

It sounds like Port Angeles, but it’s not. In Burlington, Vermont, businesses are fed up with vandalism, public nudity, open-air drug use, and needle exchanges in parks. Over 100 business owners signed a letter to the mayor demanding action.

Their story is a cautionary tale: When you ignore the business community long enough, they start to speak with one voice.

📺Watch WGME’s brief segment on Burlington’s all-too-familiar problem by clicking here.

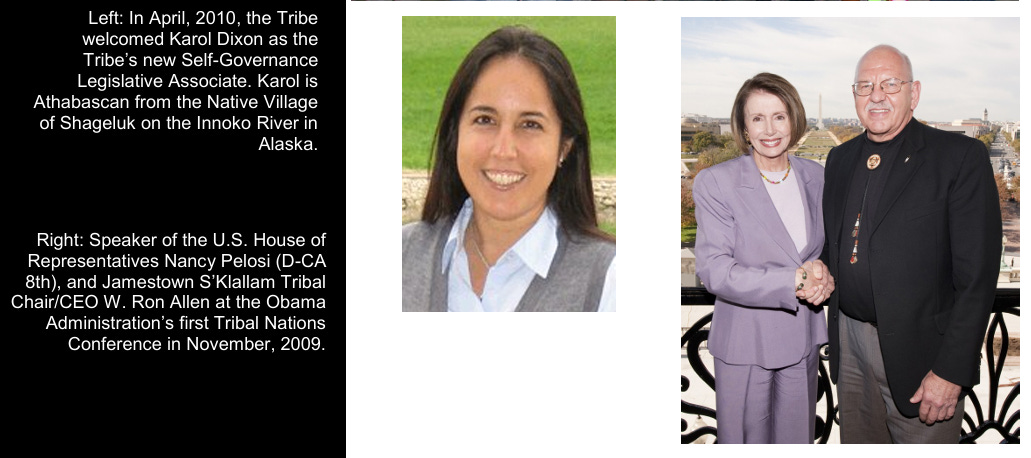

The “other” tribe raking in grants

This tribe has a lucrative casino, million-dollar homes, and a chief who met with the President on Air Force One. They also received over $28 million in federal funding. You might assume this is the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe—but no, this is the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians in California. The parallels, however, are striking.

When tribal sovereignty meets federal money and partisan politics, accountability gets murky.

📖 Read the full report at The Daily Wire to discover how a watchdog uncovered a connection between a powerful tribe and favored politicians.