From taxpayer-funded NGOs to hidden profits, selective enforcement, and opaque policies, these ten investigations reveal a troubling pattern. Each story exposes where transparency falters, conflicts emerge, and promises unravel—raising questions about whether Clallam County truly serves its residents or primarily its powerful insiders.

A familiar face

This week, a man was discovered shivering behind Tendy’s Garden on 1st Street in Port Angeles.

The Clallam County Scanner page on Facebook reported it was David Dewalt, a well-known “frequent flyer” at Clallam County Jail.

Dewalt has a documented history of arrests: 17 times in California before relocating to here to avoid recognition. Once in Washington, he sent a woman to the ER in Bremerton after head-butting her, and this summer alone, he’s had multiple stints in Clallam County Jail. Most recently, he reportedly banged on windows and yelled at employees in the Maurices store.

Port Angeles, dubbed Clallam County’s “harm reduction capital,” draws individuals whose behavior strains law enforcement and local businesses. While compassion is important, chronic offenders pose challenges: how can support coexist with public safety and economic stability? Managing repeat offenders—often linked to substance abuse and mental illness—consumes disproportionate county and city resources, raising questions about the impacts of harm reduction policies.

Roundabouts—for safety or profits?

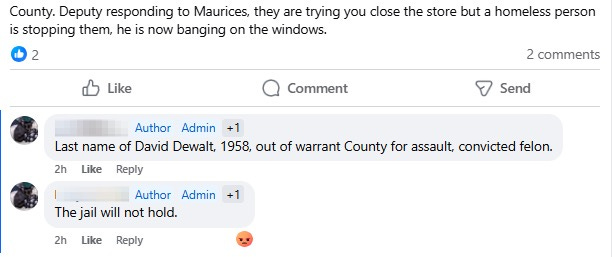

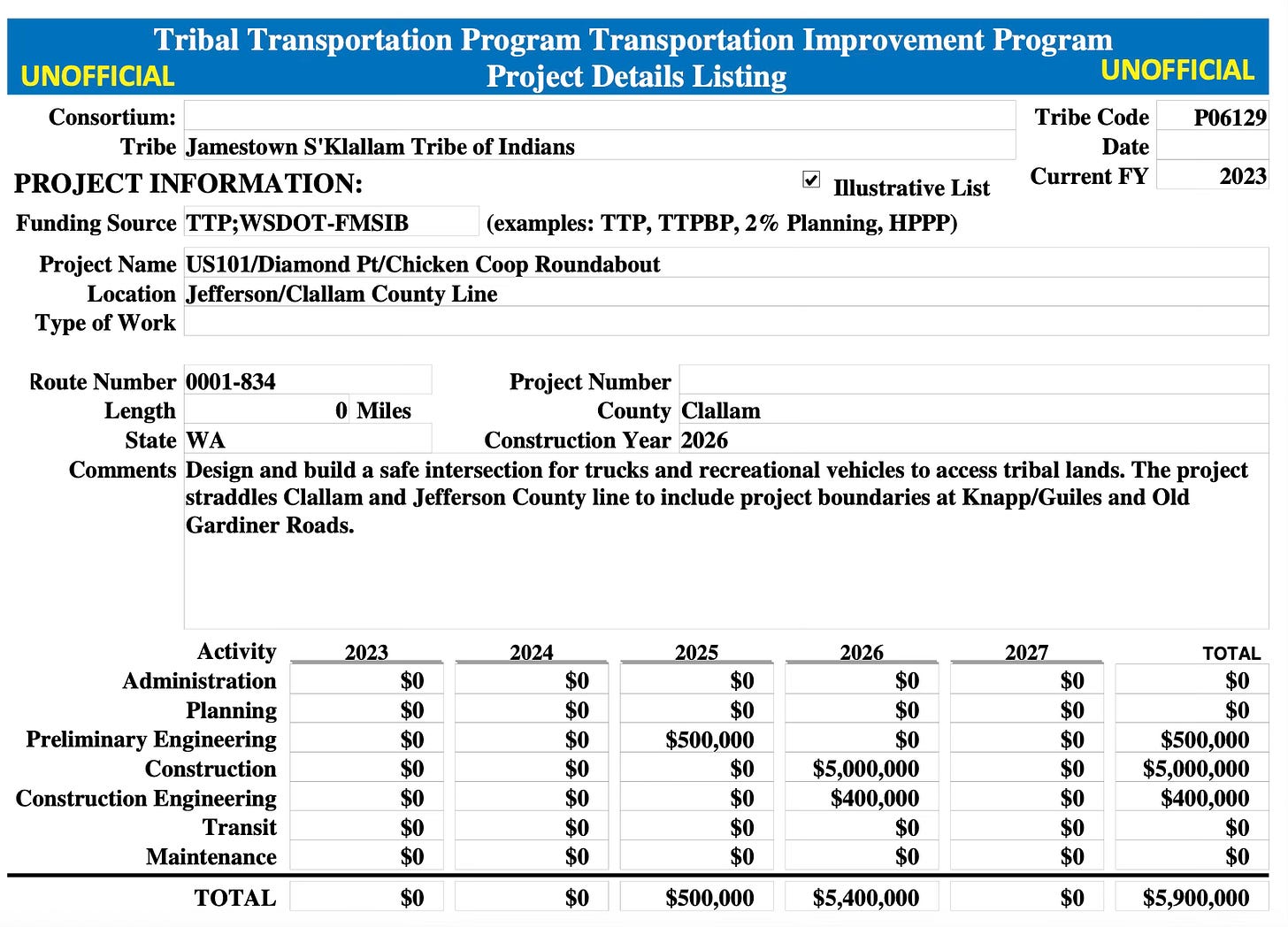

The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe is planning yet another Highway 101 roundabout—this time at the county line (Diamond Point & Chicken Coop Roads) for $5.9 million. On paper, it’s a traffic improvement. On the ground, it appears to be a strategic infrastructure investment designed to funnel cars toward the Tribe’s upcoming truck stop and convenience store on Miller Peninsula.

Another roundabout is planned in Blyn, with a third near the Tribe’s “Salish Trails” development. While touted for safety and “climate resiliency,” critics say these projects primarily funnel traffic to Jamestown’s businesses. When public funds support infrastructure that benefits tribal enterprises, the line between public good and private gain becomes unclear.

The State claims the Tribe funds these roundabouts, but much of that money comes from state and federal grants—funded not by the Tribe itself, but by taxpayers.

View the Jamestown Tribe’s upcoming transportation projects here.

One-sided solutions in homelessness discourse

Vice President of Habitat for Humanity of Clallam County, Danny Steiger, has launched a six-part series exploring homelessness on his website, Clallam County Solutions. While the articles highlight the plight of seniors—citing a 65% increase in senior homelessness—they rely almost exclusively on service provider perspectives. Missing are the voices of local business owners, residents impacted by encampments, or critics of existing homelessness policies.

Property taxes, which are increasingly cited as driving residents toward poverty, receive no attention in the article. Likewise, harm reduction strategies—central to debates about what is keeping individuals in poverty—are absent. Early indications suggest the series will favor a solution that expands NGO programs, mirroring Habitat’s own operations, rather than addressing systemic policy flaws that contribute to homelessness.

A liaison with no role clarified

Habitat for Humanity recently appointed Rick Dickinson as its “Native American Housing Liaison,” a position intended to strengthen ties with local tribes. Over the summer, Dickinson participated in the Elwha Tribe’s canoe journey and the Neah Bay canoe races. While these activities foster relationships, Habitat has refused to publicly disclose his job description, even after receiving $800,000 in county funds.

This lack of transparency raises concerns: Is Habitat constructing housing for all residents, or just for selected special interests? No announcements have been made about hiring liaisons for other communities, such as Hispanic, Asian, African American, or White populations. When public funds are involved, selective advocacy can create perceptions of favoritism and exclusion, undermining trust in nonprofit accountability.

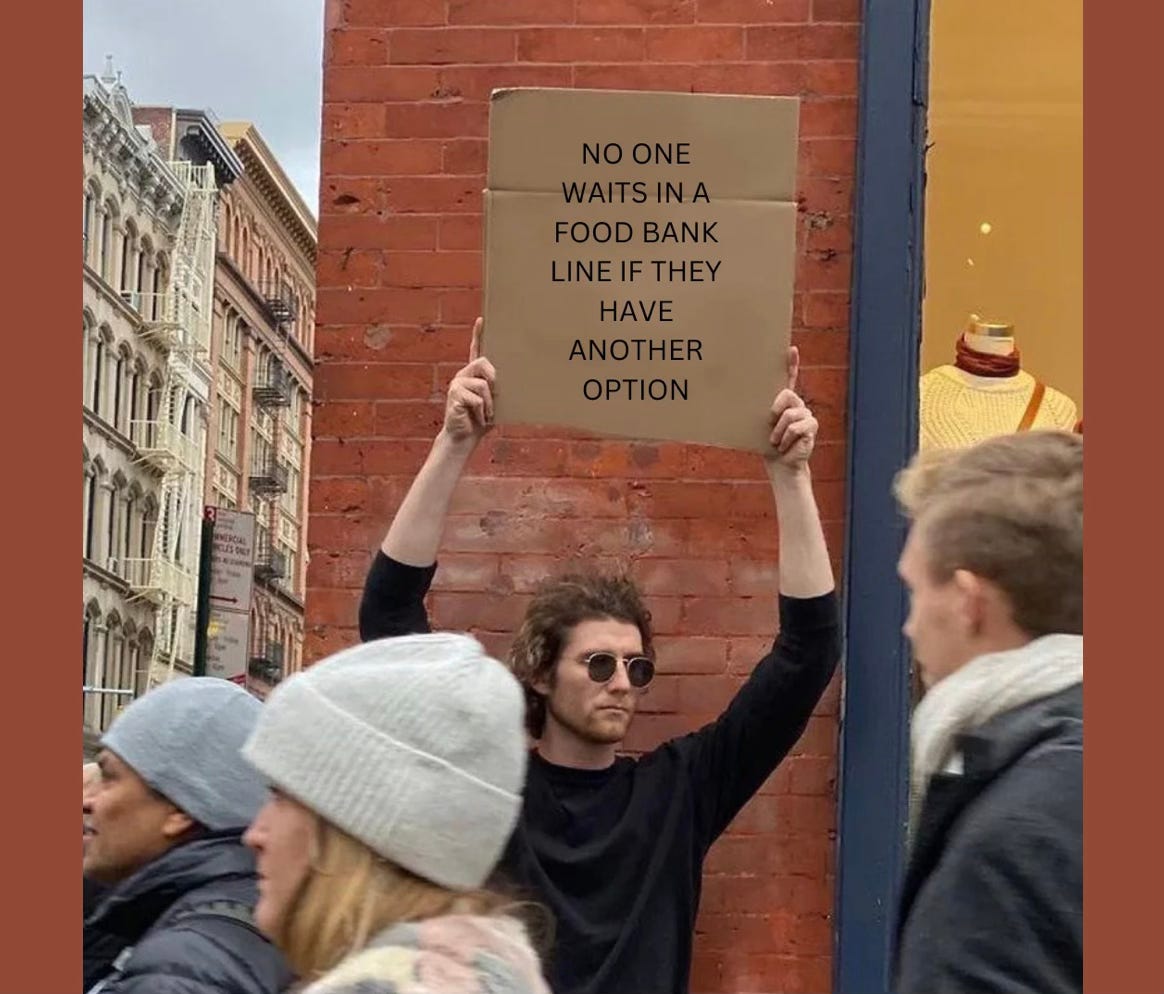

5. Barrier-free feeding—or enabling?

A day after CC Watchdog highlighted the Port Angeles Food Bank’s practice of sending children home with weekend and holiday meals, the organization published an article defending its barrier-free approach: no ID, no paperwork, no proof of income—just food for anyone who asks for it. The food bank frames this policy as a matter of efficiency, dignity, and compassion, designed to help families facing sudden crises like job loss, medical emergencies, or unexpected bills.

Critics question whether a hands-off system is sustainable or invites misuse. The food bank insists most recipients genuinely need help, but even occasional abuse strains resources, highlighting the tension between access and accountability.

While the food bank claims that “food banks don’t create poverty,” indiscriminate distribution can enable dependency and obscure the economic pressures that drive families to charity. Barrier-free policies prioritize human need over bureaucracy—but they also reveal the delicate balance between generosity and responsible oversight, and the potential for unintended consequences.

30% in a month—or a year?

Commissioner Mark Ozias publicly cited that 30% of Sequim’s population visited the Sequim Food Bank within a single month. Upon review, the figure actually reflects a 12-month cumulative reach across the boundaries of the Sequim School District.

Commissioner Ozias—himself a former executive director of the Food Bank and now a sitting board member—has amplified need figures in public forums, blurring the line between governance and advocacy. Whether by design or not, his messaging risks creating the impression of greater and more immediate demand than data may support. Transparency advocates call this a textbook conflict of interest: a county commissioner using his official platform to promote, and potentially inflate, the profile of an NGO he both once ran and still serves, all while that same organization benefits from county funding.

The food bank clarified the methodology: 11,588 unique individuals accessed services over the year, with children and seniors comprising significant portions. While impressive in scale, conflating annual data with a monthly metric risks misleading the public and underscores why officials should avoid holding positions in NGOs receiving county funds.

Commissioner Ozias declined a request to clarify his comments. However, Sequim Food Bank Executive Director Andra Smith was very responsive:

Thank you for your thoughtful email and for the opportunity to provide additional clarity regarding the numbers referenced at the Board of Commissioners meeting. Below, I’ve addressed your specific questions and also included some additional context that illustrates the growing demand for food access in our community.

Population baseline: The Sequim Food Bank uses the boundaries of the Sequim School District as our general service area. According to 2023 Census data, the Sequim School District has a population of 34,119 residents, which we use as the baseline when calculating participation percentages.

How visits are tracked: We use a client intake system that records both household and individual information. Each household is registered once, with its size reported at intake, and visits are logged when households access services. This allows us to track unique individuals, unique households, and the frequency of visits.

What the 30% figure represents: The 30% figure refers to the percentage of unique individuals within the Sequim School District who accessed Sequim Food Bank services at least once over a 12-month period. This is not a single-month measure, but a cumulative count of reach over the year.

Timeframe for reporting: Commissioner Ozias’s reference came from data I presented at our July Board meeting. At that time, we reported that more than 30% of residents in the Sequim School District had used one or more of our programs within the previous 12 months. In the meeting, the timeframe may have been heard as a single month, but it was intended as a year-long measure.

Additional context: Here is some information from our year-end report (July 1, 2024-June 30,2025)we submitted to WSDA Food Assistance:

o A total of 11,588 unique individuals — 34% of the Sequim School District population — accessed a food program at least once.

o Of these, 29% were children under 18, and 27% were seniors over 55, underscoring the broad cross-section of our community impacted.

o During this same period, 3,761 unique households accessed food services 19,857 times.

o In addition, we distributed 11,524 Weekend Meal Bags for Kids —not included in the above calculations. This is another significant program that provides children with meal and snack bags to take home over weekends. Including this program would raise the total number of individuals touched by our services even further.

Importantly, demand is rising: we have already seen a 33% increase in service need since the beginning of this year compared to the same time last year.

These numbers demonstrate the scale and urgency of food access needs in the Sequim School District. While we present statistics as transparently as possible, we also recognize that they represent real families, children, and seniors who rely on essential community services.

I hope this explanation helps clarify how the 30% figure was determined and provides a fuller picture of what we are seeing at the Sequim Food Bank. Thank you again for asking these important questions and for supporting transparency in community discussions.

Please feel free to reach out if you have any questions and I also invite you to a free event we are having at the Sequim Food Bank (144 W. Alder Street) on Saturday, September 27, from 4-6 p.m. to learn more about our programs and the impact our work is having within the community.

Sincerely,

Andra Smith

Executive Director

Sequim Food Bank

Daily dosing, daily dollars

CC Watchdog recently reported on a billboard for the Jamestown Healing Clinic, which advertised “daily dosing” for opioid use disorder. Beneath the surface, a lucrative federal reimbursement structure was revealed: $719 per encounter, with up to five daily visits per patient. A single client could theoretically generate over $3,500 per day. Although the Tribe claims the facility serves public health goals, the economics suggest a model that favors volume over long-term recovery.

The billboard initially emphasized dosing, but days after the article scrutinized the message, it was revised to include intensive outpatient care, individualized treatment, and therapy for multiple substance abuse types. Yet the daily encounter model persists, raising ongoing questions about prioritization of patient care versus revenue.

A candidate with clarity

Port Angeles City Council candidate Marolee Smith Dvorak addresses homelessness with nuance, distinguishing between those who need temporary support and those with chronic mental illness or substance abuse issues. Her approach emphasizes safety, realistic intervention, and accountability—contrasting sharply with the status quo, which often treats all homelessness as a single problem.

Dvorak’s campaign highlights a key truth: policy must balance compassion with practicality. Without understanding the distinctions among hidden, transitional, episodic, and chronic homelessness, communities risk repeating the mistakes of past decades, when well-intentioned reforms inadvertently left the most vulnerable without meaningful care.

Read Marolee’s article here and learn about a Port Angeles city council candidate who is definitely not the “status quo.”

Enforcement gaps

Port Angeles ordinances prohibit obstructing sidewalks, aggressive begging, and other forms of pedestrian interference.

Yet encampments persist, suggesting selective enforcement. The law includes exceptions for disabilities, medical emergencies, and events, but public observation reveals widespread non-compliance with no apparent consequences.

The gap between laws on paper and their enforcement exposes the limits of municipal authority when resources, priorities, or political will are lacking. Ordinances may exist in theory, but when applied unevenly—or not at all—they erode public trust and cast doubt on the credibility of local governance.

Rotary meetings, tribal secrecy, and closed-door governance

The Sequim Sunrise Rotary invited the public to hear Jamestown Tribe CEO Ron Allen speak—but only members and invited guests received access.

This raises a fundamental question about transparency in civic engagement. Jamestown CEO Ron Allen leads the county’s second-largest employer and arguably its most influential governing body in eastern Clallam County. By most appearances, it is Allen alone who decides what the county will do, when it will do it, and how much it will cost.

Yet while the Tribe does not appear at county work sessions or public meetings, our own elected representatives are left to draft letters of “concern” or “apology” to the Tribe. Meanwhile, the Tribe finds time to meet privately with civic organizations—out of public view. When decisions that shape Clallam County happen behind closed doors, citizens are denied insight into the policies that affect them most.

Transparency demands open forums, public access, and honest communication. If the direction of our county is being determined, why wouldn’t even a Zoom link be shared with the public? Secrecy isn’t governance—it’s the opposite of democracy.