Clallam County residents were told higher taxes were needed to save Olympic Medical Center—but now they’re being turned away from the very hospital they’re funding. As services shrink, clinics close, and financial transparency disappears, county commissioners who pushed the levy hike are silent. Where’s the accountability for a failing public hospital sitting on dozens of vacant, tax-exempt properties while patients are left without care?

“I am taxed for this facility, and I cannot get an appointment.”

That was the message from Clallam County resident Denise Lapio during a recent public comment to the Board of County Commissioners. Lapio described how, despite having established primary care at Olympic Medical Center (OMC) years ago, she had not had an appointment in over three years. When she recently tried to get in, she was told she would be considered a new patient—and OMC is not taking new patients at this time.

“I just had my taxes extremely increased due to lifting that levy lid that this board endorsed,” she told the commissioners. “I just wanted to give you an update—from a personal experience—about what my tax increase did to me.”

She eventually got an appointment, but only after being referred to the Jamestown Family Health Clinic in Sequim. The receptionist there confirmed that more and more patients were being turned away from OMC.

This moment highlights a growing concern among residents: Where is the return on investment?

A year ago, a different story

In 2024, the Clallam County Commissioners endorsed Proposition 1, urging voters to support lifting the levy lid for OMC. Voters were told that this tax hike was necessary to preserve essential hospital services. Now, residents like Lapio are being denied care, while the amount of property taxes paid to the hospital has doubled for many homeowners.

And yet—the commissioners have gone quiet.

When asked recently to comment on the growing number of complaints and concerns, including clinic closures and financial transparency at OMC, the county commissioners declined to comment.

If elected officials are going to urge the public to vote one way or another, isn’t it fair to expect them to be available when those decisions play out? Shouldn’t they be accountable when the promises don’t match reality?

A hospital in trouble—with taxpayer support

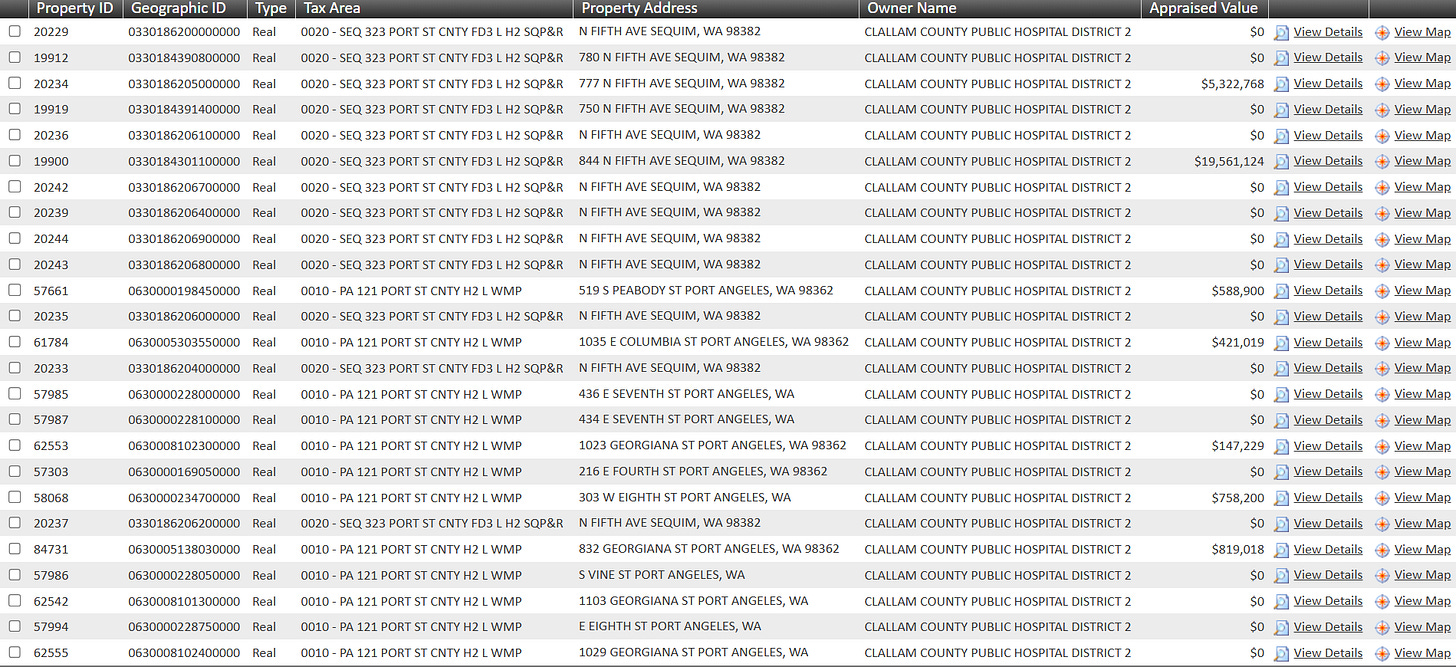

Despite the public’s generous show of support, OMC has been struggling. One reason may be its questionable real estate strategy. Public records show that OMC owns over 50 properties across the county.

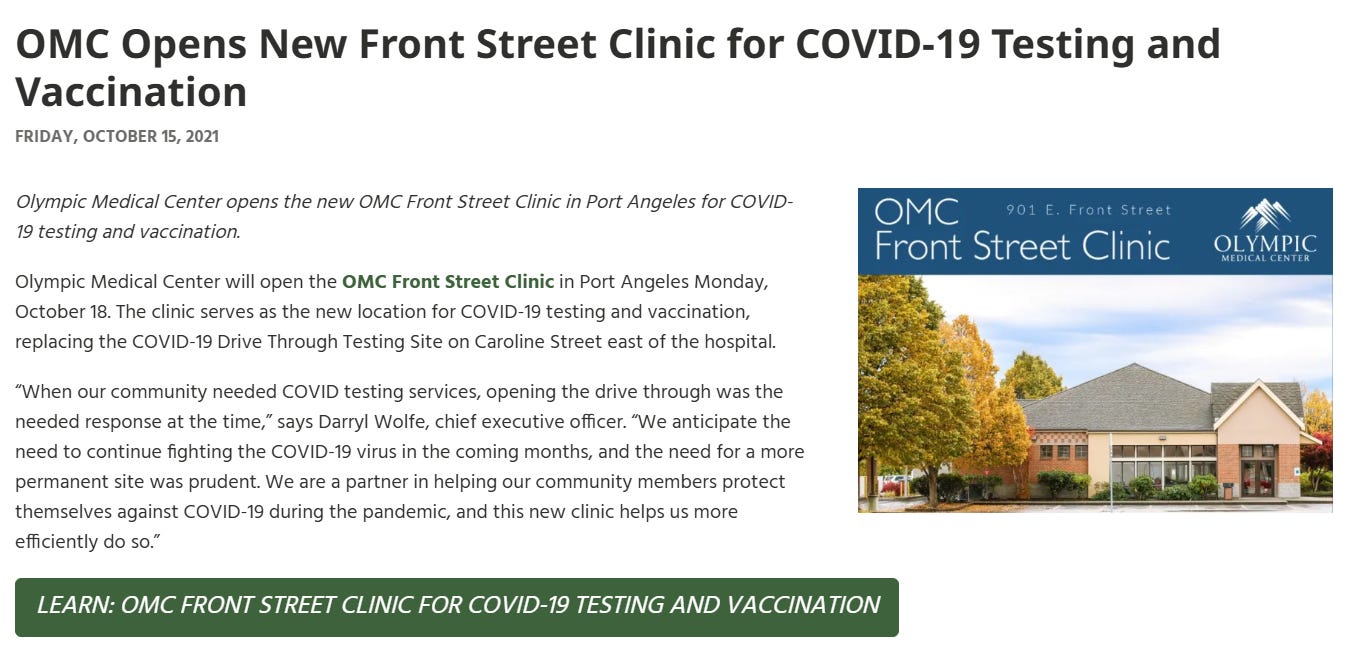

Some have clinical functions—but many are vacant, and a few raise eyebrows. Take 907 E. Front Street in Port Angeles—the former Wells Fargo building.

OMC purchased the site in 2021 for $1.1 million, used it briefly for COVID-19 testing, and now it sits vacant.

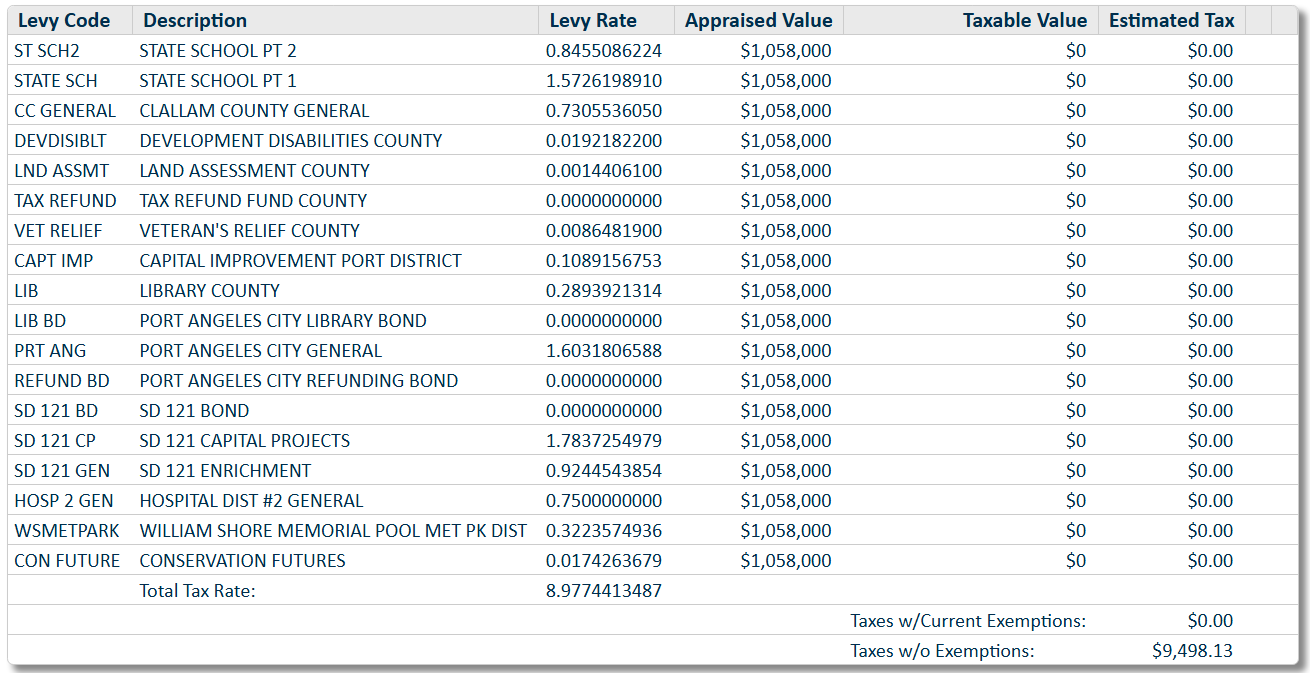

That prime Front Street real estate is tax-exempt, meaning the hospital saves on taxes—but local schools, libraries, and even the hospital district itself lose out on nearly $10,000 in annual property tax revenue from that one parcel.

There are dozens more.

This raises a fair question: If OMC needs money so urgently that taxpayers had to step in, why not sell surplus properties and put them back on the tax rolls?

Selling even a fraction of the underused or vacant parcels could both generate revenue and reduce the hospital’s maintenance and insurance costs—while providing the community with new housing, commercial opportunities, and tax contributions.

A land deal worth reexamining

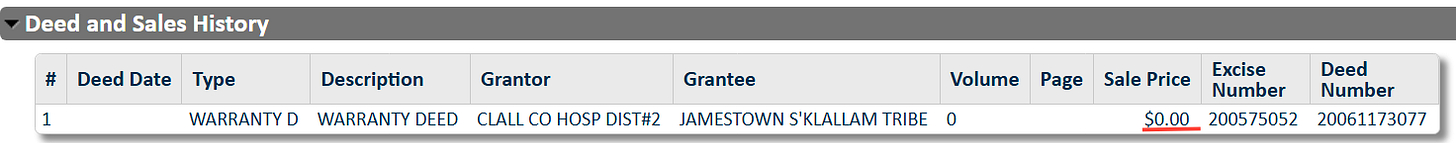

The hospital's real estate dealings don’t end there. At one point, OMC owned land behind its Sequim campus. That land was donated, free of charge, to the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe—even though it had an appraised value. The Tribe then built a clinic there.

It’s not clear how much the Tribe’s clinic earns, as tribal enterprises are not subject to standard public financial disclosure. However, what is clear is that the land once owned by the public was given away—and now serves a competing clinic, while OMC patients are being turned away and the Sequim satellite campus may close.

Transparency fading

Adding to public frustration is the lack of financial transparency. For months, OMC had stopped publicly releasing its financial statements—a major concern, especially after voters were asked to trust that their tax dollars would be used to preserve care.

Instead, residents are now seeing shrinking services, shuttered clinics, and a hospital board and CEO that appear more focused on managing property than patient access.

So where are our leaders?

It’s not unreasonable to expect Clallam County’s elected commissioners—who went on record urging support for a tax increase—to explain why constituents like Denise Lapio are now being told there’s no room at the hospital they pay for.

If the commissioners felt strongly enough to tell voters how to vote, they should feel responsible enough to speak up when those voters ask questions. And if they’re not willing to answer for the outcomes of their endorsements, maybe they should think twice about making them in the first place.

Reminder: Glen Morgan comes to Sequim tonight!

Government watchdog Glen Morgan is bringing his popular DOGE training to the Sequim Elks Lodge tonight. For just $15, attendees will learn how to dig into public records, track government spending, and expose misconduct. Glen’s “We The Governed” platform has inspired troves of citizen investigators across Washington. Now he’s here in Clallam County, offering tools for anyone ready to be a watchdog.

Sequim Elks Lodge #2642. 143 Port Williams Rd, Sequim

Thursday, July 17th

Registration starts at 5:15 pm

Event Start: 6:00 pm

Ends: 8:30 -9:00 pm

Cost: $15.00

The Elks club bar will be open, where you can purchase alcoholic drinks and sodas. Coffee and tea will be available.