In an era when anyone can livestream from their phone, Olympic Medical Center refuses to record its own public meetings—making it harder for working families to follow what’s happening at the hospital they own. Recent revelations show why: a $248,000 consulting contract signed in secret, an interim CEO costing $50,000 a month, and board meetings that cut off public comment early. For a hospital that raised taxes under threat of service cuts and now teeters on insolvency, this secrecy isn’t just tone-deaf—it’s a betrayal of public trust.

It’s 2025. Toddlers can navigate iPads, anyone can livestream to the cloud from their pocket, and streaming entertainment options are endless. Yet somehow, Olympic Medical Center (OMC)—the largest employer in Clallam County—can’t manage to record and upload its own board meetings for the public it serves.

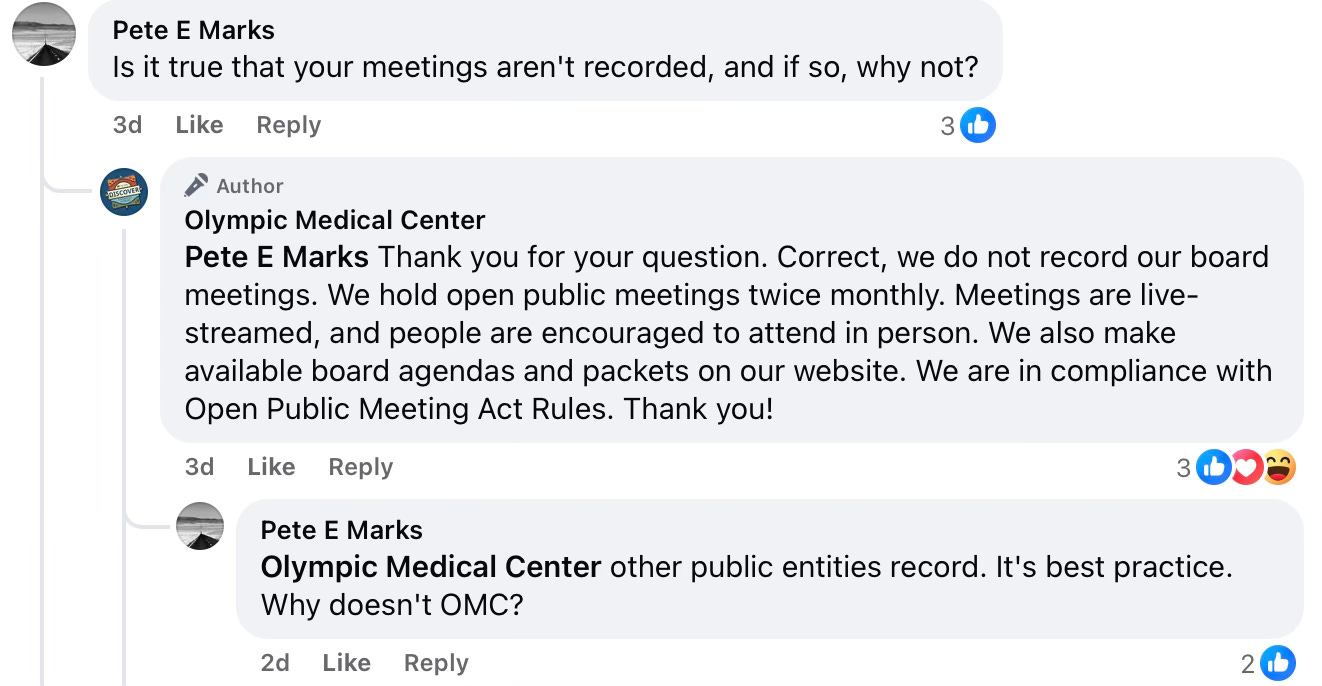

When pressed on Facebook, OMC admitted:

“Correct, we do not record our board meetings. We hold open public meetings twice monthly. Meetings are live-streamed, and people are encouraged to attend in person. We also make available board agendas and packets on our website. We are in compliance with Open Public Meeting Act Rules.”

Translation: we don’t have to, so we won’t.

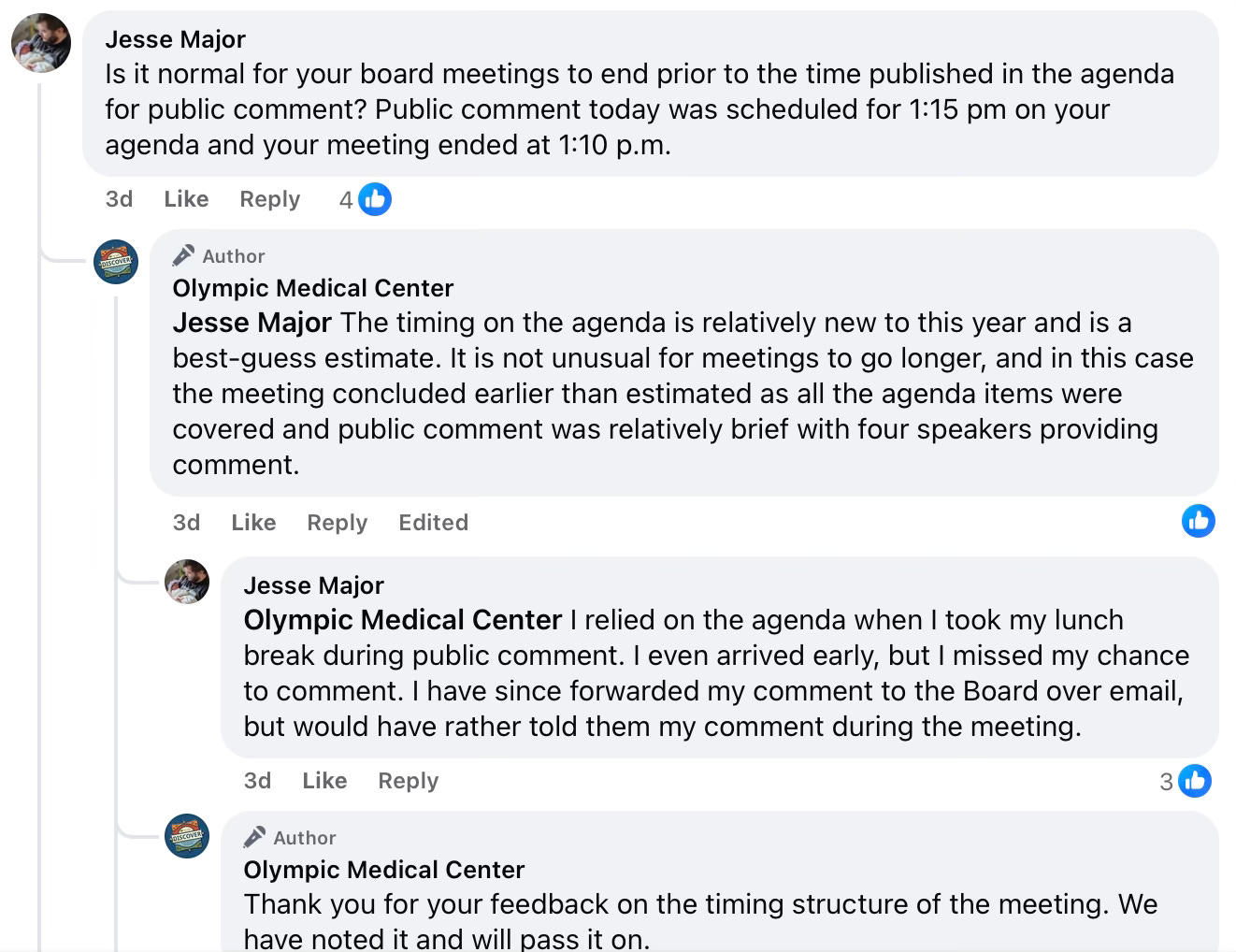

Cutting off public comment

One resident recently discovered that even attending in person doesn’t guarantee your voice will be heard. OMC’s agenda scheduled public comment for 1:15 p.m.—yet the meeting ended at 1:10, shutting people out. When questioned, OMC brushed it off: the agenda times were “best guesses.”

But for taxpayers on a lunch break, those “guesses” meant losing their only chance to speak. It’s a pattern: decisions that should welcome public input instead close doors.

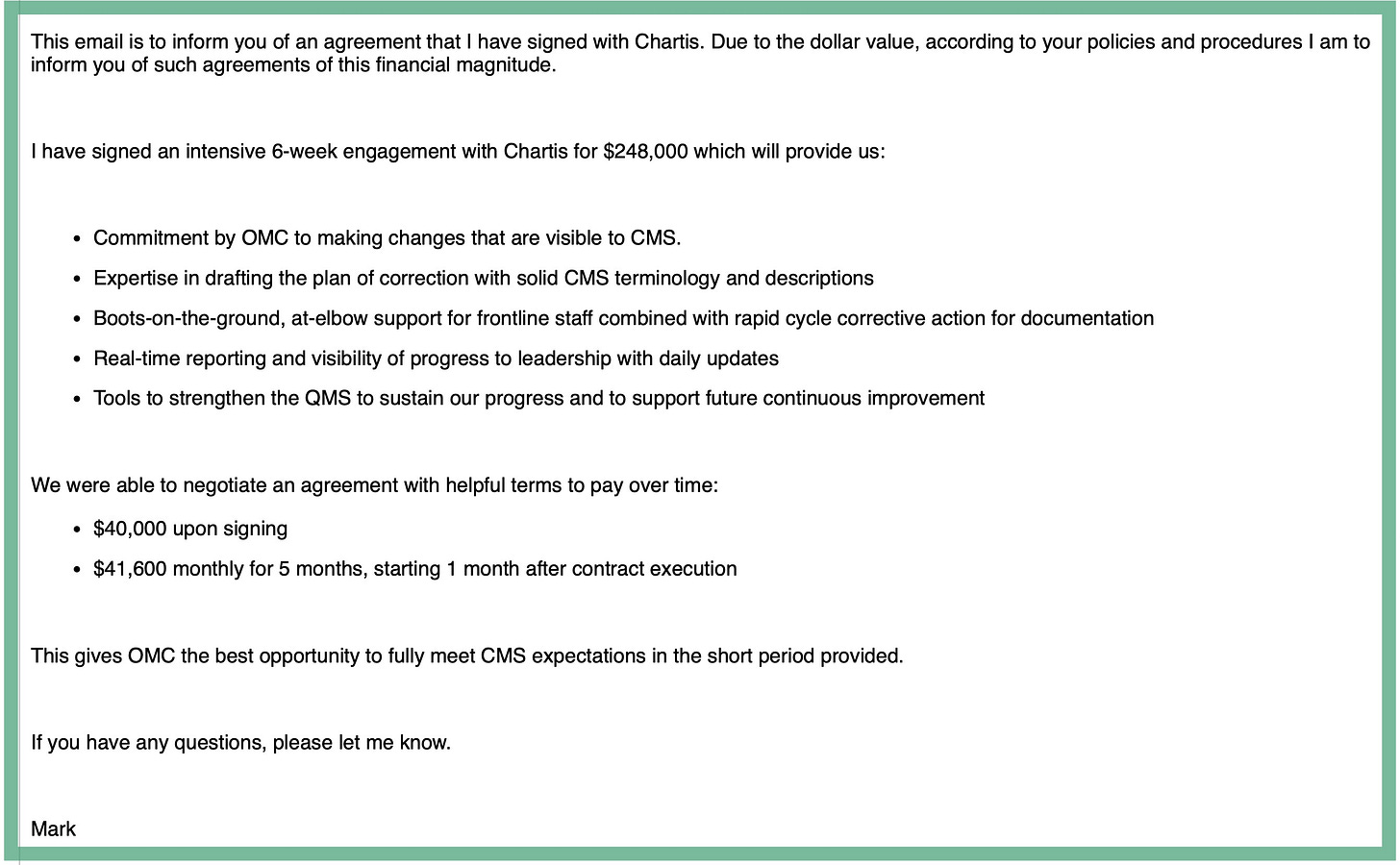

The $248,000 secret contract

Perhaps the real reason OMC prefers silence is what’s happening behind the scenes. At the September 3rd meeting that ended early, the board skipped discussion of a major agreement with Chartis, a private healthcare consulting firm. Yet internal emails reveal interim CEO Mark Gregson had already signed a $248,000, six-week contract with Chartis on August 26th—a week before the board meeting.

Gregson, who collects $50,000 a month as interim CEO (plus travel and lodging expenses), was hired to fix OMC. But in less than a week on the job, his “solution” was to sign off on a secret $248,000 consulting deal, essentially paying outsiders to do the very job taxpayers are already paying him to do.

And the timing? Conveniently, Chartis pushed CMS to extend OMC’s compliance deadline to October 10—three days after the Chartis six-week contract expires. Another extension would mean another expensive “re-up.”

The Chartis paradox

Chartis is no stranger to OMC. Just last year, the same firm declared OMC one of the nation’s “Top 100 Community Hospitals” for the ninth year in a row.

That recognition came a year after OMC nearly ran out of cash and amid allegations that an ER doctor sexually assaulted multiple patients.

Now, the firm that once praised OMC is being paid to save it. Chartis itself is owned by Blackstone, a private equity giant tied to fraud allegations and notorious for pushing hospitals toward for-profit models.

An affiliation with UW Medicine

Meanwhile, Gregson also announced OMC had signed a letter of intent with UW Medicine for a potential affiliation.

UW’s own land acknowledgment cites the Coast Salish peoples, but what Clallam County residents want acknowledged is whether their hospital will continue prioritizing patients over consultants and corporate deals.

A hospital in crisis—but whose hospital?

Morale among OMC employees is collapsing. Internal emails call the Chartis deal “criminal” and leadership “incompetent,” with staff openly speculating whether the hospital is being positioned for a fire sale.

One staff member commented that, “It just speaks to the level of all around incompetence that OMC needs to spend who-knows-how-much (millions?) on consultants over the years to tell them how to do their jobs. What a waste. Has anybody been running the show?”

The most troubling fact is this: OMC is not a private corporation. It is a public hospital district—owned, funded, and governed by the very residents now being shut out of meetings and denied answers.

When the county’s largest employer hides multimillion-dollar decisions from taxpayers while raising property taxes and cutting services, the problem goes far beyond mismanagement—it is a full-blown crisis of transparency.

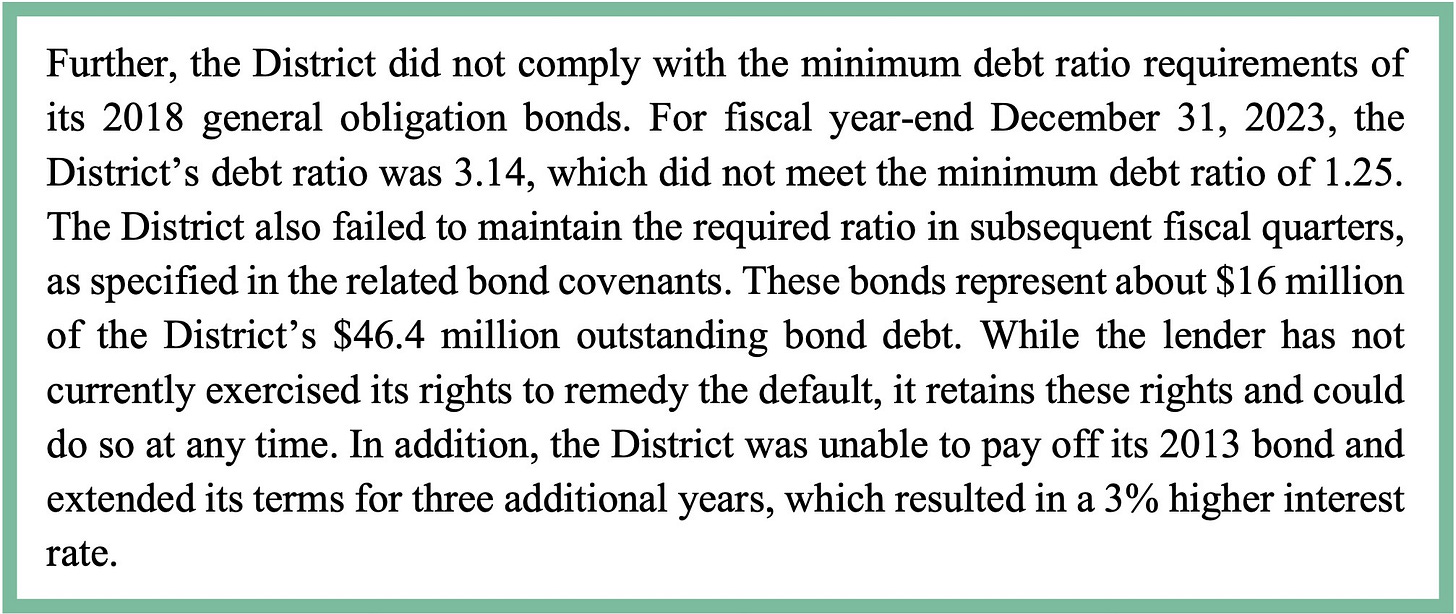

The State Auditor’s recent accountability audit drives that point home. OMC is in default on its 2018 general obligation bonds, failing to meet debt ratio requirements on $16 million of its $46.4 million outstanding debt—leaving lenders free to act at any time. The District also couldn’t pay off its 2013 bond, forcing a costly three-year extension at a higher interest rate.

This is a hospital already notorious for losing tens of millions, defaulting on bond obligations, and facing repeated threats of closure for Medicare violations. Regulators have conducted four site visits since February, yet critical deficiencies remain uncorrected. And through it all, OMC continues to lean on taxpayers for more money while keeping them in the dark about where it’s going.

The question now isn’t just whether OMC can survive—it’s whether the public who owns it will ever be allowed back into the room.