From abandoned activist camps and political gatekeeping to unchecked tribal influence and public safety risks, this roundup dives into the contradictions hiding in plain sight. Who gets heard? Who gets paid? And who really benefits when transparency gets tossed aside? In Clallam County, the stories that slip through the cracks are often the ones that matter most.

Legacy or left-behind garbage?

Mitch Zenobi, owner of Mitch Zenobi Tree Service, posted a Facebook video confirming the end of a dramatic protest in the Elwha watershed. Environmental activists—led by Charter Review Commissioner Nina Sarmiento—vacated the site after weeks of attempting to block the Parched Timber Sale. The tree they sought to “save” was cut down. In its place? Garbage and debris scattered across the forest floor.

Commissioner Sarmiento, now calling for a new county-level Water Steward Department, has floated plans to fund it through cuts to public safety or tax hikes.

The timber harvest she tried to halt could generate over $1.4 million for local services like schools, roads, libraries, and fire districts. Meanwhile, the “legacy tree” they tried to protect? Zenobi says it was only about 50 years old.

Follow Mitch Zenobi’s adventures in the timber industry on Instagram and Facebook.

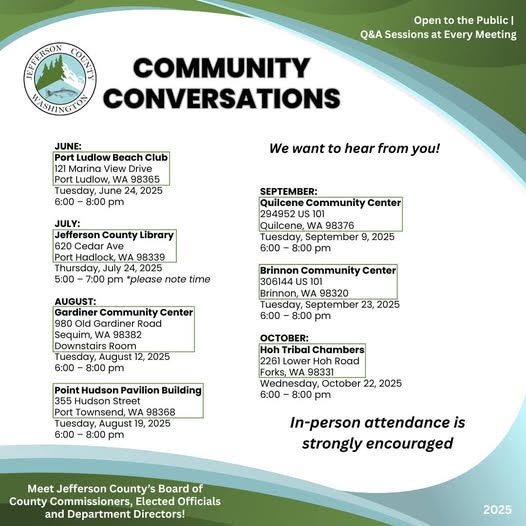

Jefferson County’s listening—why isn’t Clallam?

The last Clallam County town hall took place in October, nine months ago. That event resulted in a $369,000 contract oversight being caught by a private citizen, John Worthington. Since then? Silence. Commissioners now cite scheduling and budgeting constraints to avoid further open forums.

Across the county line, Jefferson County commissioners are holding “Community Conversations” all summer—complete with Q&A—in seven different locations. What will it take for Clallam’s leaders to see public dialogue as an asset, not an inconvenience?

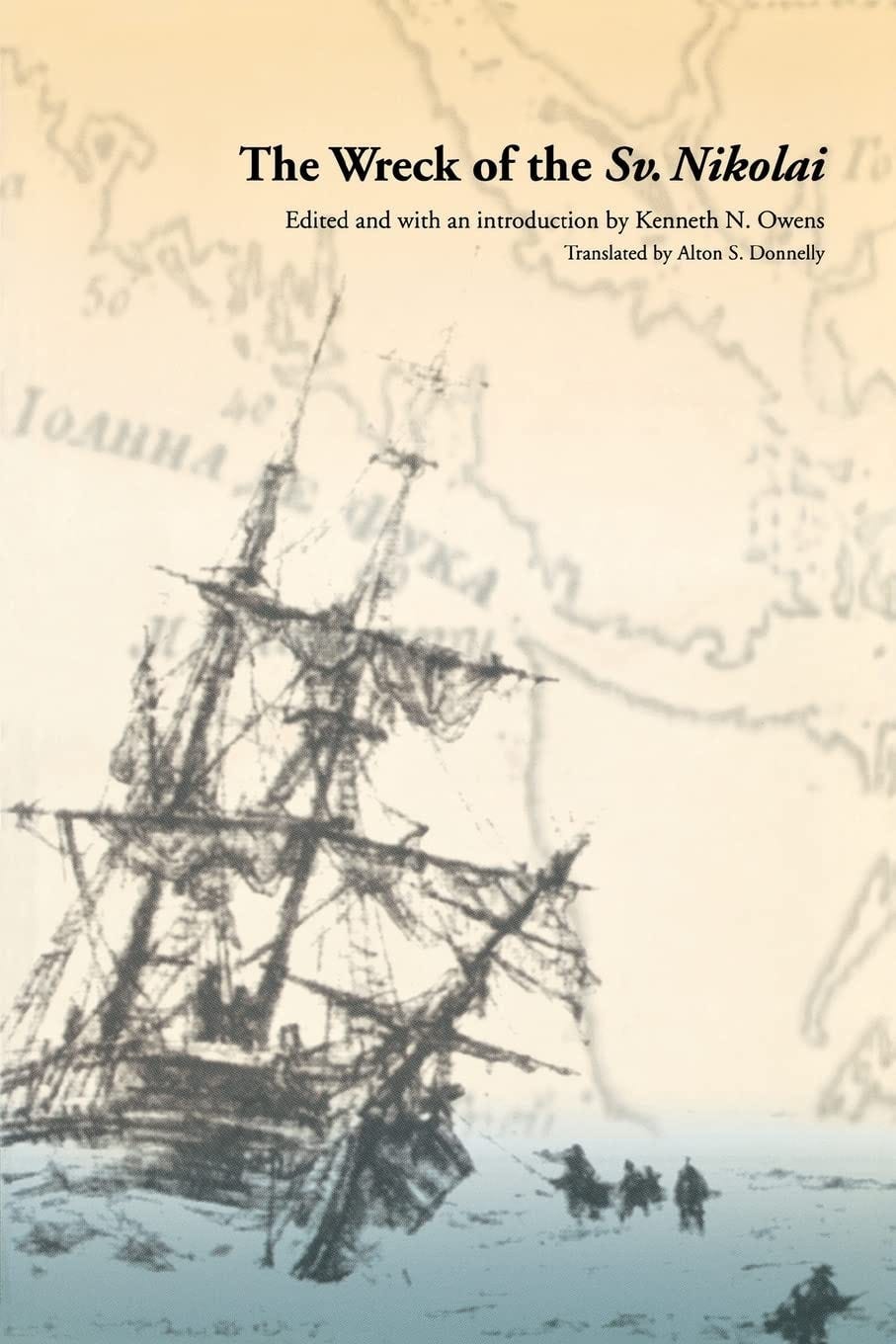

Indigenous slavery before colonizers arrived?

A historical account of the 1808 wreck of the Russian ship Sv. Nikolai upends the modern narrative that only Europeans brought violence or slavery to the Northwest.

Russian survivors were enslaved by Hoh, Quileute, and Makah tribes

Captives were held for nearly two years

Tribal slavery was institutional: slaves were traded, inherited, and sometimes sacrificed

The past is complicated. So are the stories we choose to remember—or erase.

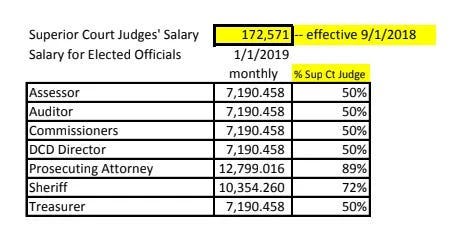

What do elected officials earn? Here’s the pay scale

Transparency starts with the basics. Here's what Clallam County’s elected officials earned monthly six years ago, based on the salary scale tied to Superior Court judges:

Here’s what they earned in 2023.

A 26% increase over four years. Taxpayers should know exactly what they’re getting—and paying—for.

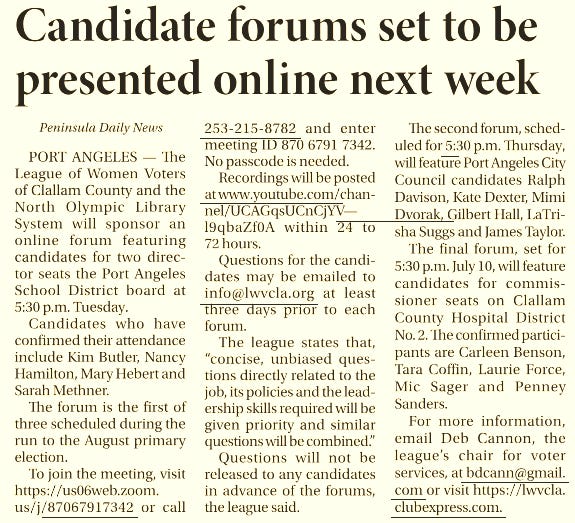

Organization vetting your questions—so you don’t have to

The Clallam County League of Women Voters is gearing up for its candidate forums. They encourage the public to submit questions—so long as they’re “unbiased.” In reality, those questions are curated and filtered by the League. If you’re lucky, yours might make it to the stage.

Despite branding itself as a nonpartisan organization, the League has partnered with Indivisible Sequim—an openly left-wing political group.

Do they truly represent unbiased civic engagement, or are they the bouncers at democracy’s door?

Dangerous loophole?

A recent arrest near Swain’s involved a suspect hiding in Jessie Webster Park. A citizen recognized the name and searched the Washington Sex Offender Registry. Nothing. But on the Makah Tribe’s registry? There he was—convicted of molestation and rape of a child in 1997.

His primary residence is listed as Neah Bay, though he was believed to be living in Port Angeles. Tribal registries don’t automatically sync with those of the County and State. Is this a gaping loophole that puts vulnerable residents at risk?

Land Acknowledgement—then budget cuts

Graduates at Peninsula College’s 2025 commencement first listened to a land acknowledgement—in S’Klallam, then English— welcoming attendees to the Klallam Territories, stating that tribal members protect and care for these lands, and that their rights are protected by treaty.

The college is cutting 7% of its budget—$2.2 million—including adult language and enrichment courses. But Makah and S’Klallam language programs remain untouched. What gets prioritized in times of scarcity says a lot about educational values.

Armed standoff

Last week, 37-year-old Justin Cox barricaded himself inside a Carlsborg home and fired 25–30 rounds at law enforcement. He has seven felony convictions, wasn’t allowed to possess a firearm, and now faces several counts of assault against officers.

Back in 2019, Cox was caught passed out in a stolen car with methamphetamine. He kicked out a patrol car window, escaped a moving vehicle, and was later tackled and arrested. In a county that hands out free meth pipes, is any of this a surprise?

You might be funding international relief instead of your community

In a Sequim Gazette article, Colleen Robinson, CEO of Habitat for Humanity of Clallam County, confirmed that in 2022, the organization sent $21,000 to Ukraine using “undesignated funds.” Since 1991, they’ve sent over $400,000 overseas.

Most donors likely believe their money helps build homes locally. But unless you explicitly earmark your donation, it could end up funding international projects—while local needs remain unmet.

In other words, Habitat for Humanity begs for private donations and hundreds of thousands of your tax dollars while donating to international causes.

Endorsements that speak volumes

As Councilmember Latisha Suggs seeks re-election to the Port Angeles City Council, she does so with endorsements from the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe (of which she is a member) and Navarra Carr—who recently claimed that Clallam County residents are merely “guests” on tribal land.

On her campaign site, Suggs touts a long list of initiatives—ranging from salmon restoration to climate resilience. She also serves as Chair of the Marine Resources Committee, a county agency, and recently signed a letter calling for the relocation of residents from the 3 Crabs neighborhood.

But when her key supporters frame longtime locals as mere “guests” on the land, it’s worth asking: when she says “together,” does that really mean all of us?

Fiscal restraint, not higher taxes

Port Angeles City Council candidate Marolee “Mimi” Smith Dvorak is calling for a Taxpayer Bill of Rights, limiting tax increases to inflation or public vote. Smith criticizes proposed tax hikes “for the arts,” and warns of an economic future burdened by tax increases and unchecked government growth.

Her message: government creep isn’t always dramatic—it’s slow, incremental, and dangerous. Like the ancient Chinese punishment of lingchi: death by a thousand cuts.

Read more of Mimi’s musings about Port Angeles politics here.