In Clallam County, taxpayer-funded grants meant to promote “equity” are increasingly going to select groups—while many struggling rural communities are left behind. From exclusive funding rules to electric vehicles for well-connected tribal programs, question whether identity-based priorities are overriding actual community need. Who decides what’s fair—and who’s footing the bill?

In economically stagnant Clallam County, "equity" is a word that gets used often—but doesn't always mean what it seems. While local families struggle with inflation, housing costs, and limited services, millions in state and federal funding—paid for by you and every other taxpayer—continue flowing into the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, an organization that reported $86 million in revenue in 2024, according to its own figures.

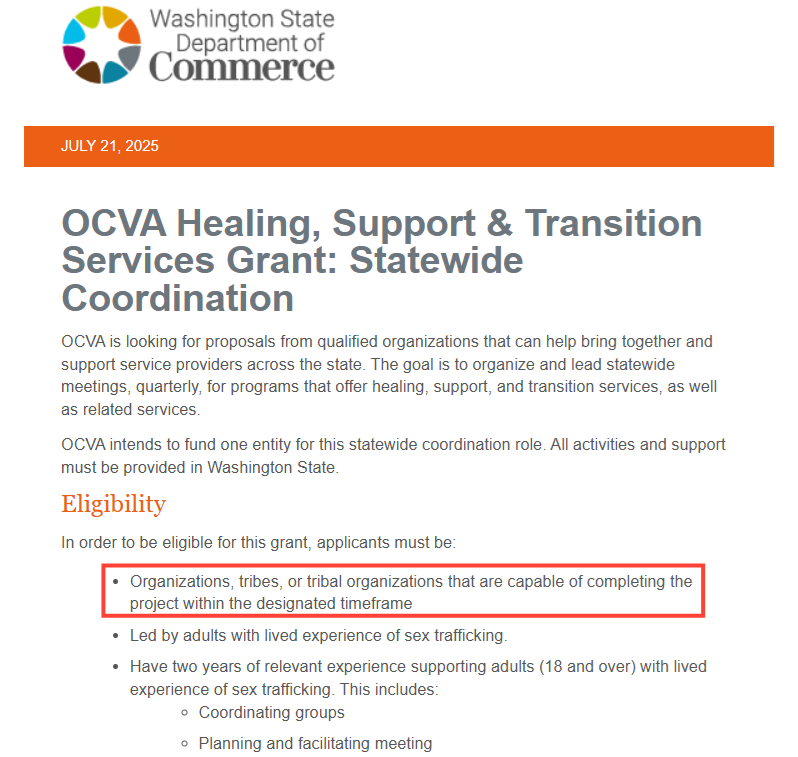

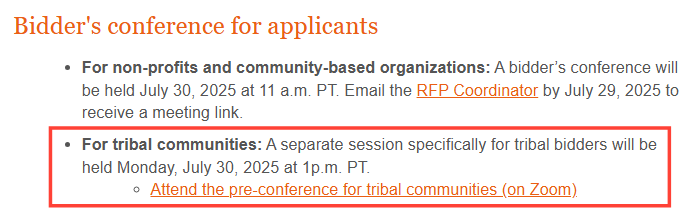

This year, the Washington State Department of Commerce opened up multiple grants designed to support vulnerable and underserved populations. The OCVA Healing, Support & Transition Services Grant offers funding for groups that coordinate healing programs for survivors of sex trafficking—so long as they are "led by adults with lived experience of sex trafficking."

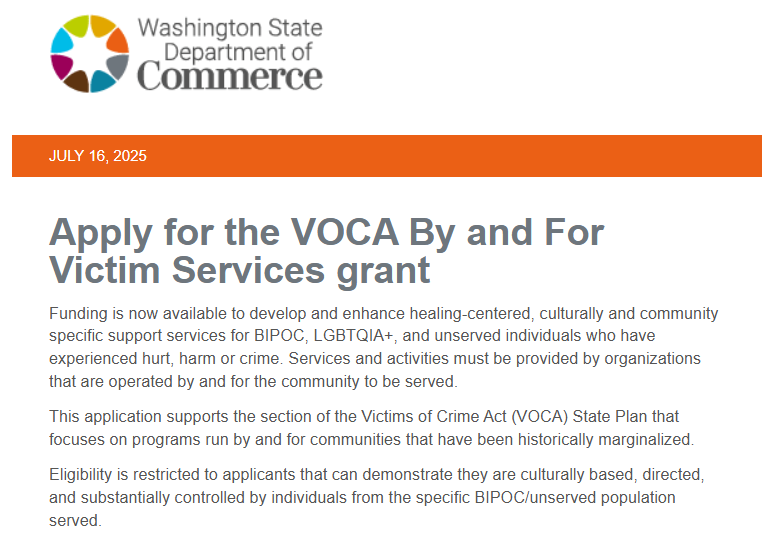

A separate VOCA By and For Victim Services grant is targeted at “BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and unserved individuals,” with eligibility strictly limited to organizations that are “culturally based, directed, and substantially controlled by individuals from the specific BIPOC/unserved population served.”

These grants are part of a growing trend in Olympia and D.C.—one where public dollars, funded by the working families of Clallam County and beyond, are allocated not based on shared economic need or community-wide hardship, but on demographic identity. And in Clallam County, where the median income remains well below the state average and poverty is widespread, this kind of prioritization raises fundamental fairness questions.

At the same time, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe continues to receive substantial grant funding from other taxpayer-supported programs. In their latest newsletter, the Tribe celebrated the purchase of two new electric utility vehicles (UTVs), funded by a Bureau of Indian Affairs Tribal Resilience grant—a grant underwritten by federal taxes and intended to support environmental adaptation and emissions reduction.

These vehicles were delivered to the Dungeness River Nature Center and the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge.

According to Robert Knapp, the Tribe’s Environmental Planning Program Manager, the goal is “greenhouse gas emission reduction.” The electric vehicles are expected to save on fuel, reduce noise, and help patrol natural areas with less environmental disruption.

Tribal Land Steward Powell Jones praised the quietness of the new UTVs, saying it “fits the mission of both places,” while Wildlife Refuge Manager Fawn Wagner noted that the new machines will support habitat monitoring, crab control, and garbage pickup “with lower emissions, less noise, and a longer lifespan.”

It’s also worth noting that the Tribe’s call for quiet operations to minimize disturbance to wildlife seems at odds with another of their initiatives: launching a commercial non-native oyster farming operation inside the very same wildlife refuge.

How do we reconcile the image of silent electric UTVs protecting fragile habitat with the noise, boat traffic, and ecological disruption of an industrial aquaculture project in that exact location?

These are noble goals—but many Clallam County residents are asking hard questions about priorities. Should limited public funds really be used to upgrade UTVs at a wildlife refuge already supported by both tribal and federal dollars—while sheriff’s deputies in the West End wonder if backup will arrive when they respond to a crisis?

The Tribe’s argument: systemic inequity

The Tribe has often positioned itself as a victim of underfunding—particularly at the federal level.

In May 2024 congressional testimony, Tribal Chairman W. Ron Allen wrote:

“Funding levels are severely deficient and unable to address our Tribal communities’ unmet needs; and these unfulfilled Federal obligations continue to grow exponentially on an annual basis.”

He continued:

“American Indians and Alaska Natives continue to rank near the bottom of all Americans in terms of health, education, and employment status. These harrowing statistics and funding inequities demand a shift in the current governmental appropriations paradigm…”

That may well be true in many regions across the country. But in Clallam County, many residents are beginning to wonder whether the pendulum has swung too far the other way—where tribal entities enjoy exclusive access to grants, vehicles, and federal initiatives, while the rest of the public is left with budget cuts, program closures, and higher local taxes to make up the difference.

The Tribe has invested in impressive initiatives—from a new healing campus in Sequim, to electric vehicle fleets, to high-end tourism ventures. But as public dollars increasingly follow identity over demonstrated need, it’s fair to ask:

Where does that leave the rest of Clallam County—the loggers, teachers, waitresses, and fixed-income seniors who still pay the bills but can’t access the benefits?

Is it equitable when a Tribe of 209 local members, with $86 million in revenue receives taxpayer-funded vehicles while communities like Beaver and Diamond Point go without basic services?

Is it equitable when only organizations “by and for” specific demographic groups can apply for crime victim funding—effectively excluding many local nonprofits that serve diverse, rural, or economically mixed populations?

And is it consistent to claim environmental sensitivity in one breath, while commercializing a national wildlife refuge in the next?

Follow the money

"Equity" should mean fairness and balance. But when funding decisions are based on who you are—not what your community actually needs—trust erodes.

As our leaders and agencies pursue equity-driven policies, we must be clear about who is being served—and who is paying for it. Because in the end, whether it’s a grant-funded UTV or a taxpayer-subsidized clinic, these dollars don’t come out of thin air. They come from your paycheck.

And in Clallam County, where every dollar counts, that question deserves a serious answer.

Last Equitable Wednesday, readers were asked if, when reviewing local grant decisions, what was most concerning. Of 159 votes:

23% said, “Lack of transparency”

38% said, “Potential favoritism or inequity”

37% said, “Waste of taxpayer dollars”

2% said, “I’m not concerned”