Clallam County’s Charter Review Commission is pushing a deeply unpopular Water Steward proposal despite 70% public opposition — and instead of listening to voters, they’re taking cues from government agencies and the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. Unelected actors are shaping policy that could restrict residents while exempting a sovereign nation. If the public doesn’t regain control of the charter, they may soon lose control of their water.

Despite clear public opposition, the Clallam County Charter Review Commission (CRC) is forging ahead with a controversial proposal to create a “Water Steward” position within county government. The idea, first introduced as a benign, non-regulatory advisory role, has morphed into something that now has many citizens asking: Is this really about protecting water, or expanding government control over it?

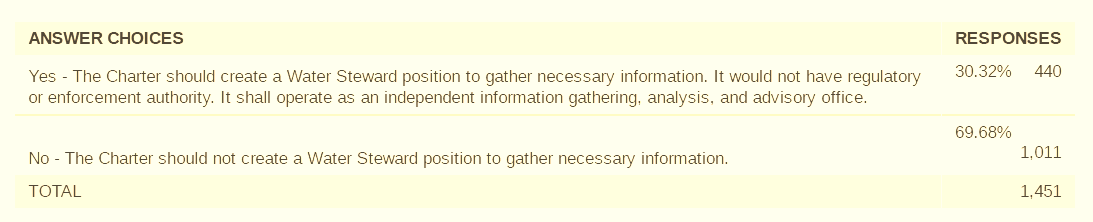

A recent public poll showed over 70% were opposed to creating the new position.

Yet the CRC’s Water Steward Subcommittee continues to explore a charter amendment — a permanent change to the county’s foundational document — that would embed the role into county government.

Mixed messages and growing confusion

Although CRC members have repeatedly insisted the position is strictly “non-regulatory,” meeting notices continue to mention “county water management.” That contradiction isn’t just semantics — it’s shaping public mistrust.

Even Water Steward Committee member Nina Sarmiento seemed uncertain about the position’s scope. When questioned at a meeting about references to “management,” she replied, “I don’t know why that was in the description.” But later in the same discussion, she acknowledged that the steward’s findings would be given to departments to help them decide if “management needs to occur, proactive or reactive.”

So which is it — advisory or a stepping stone to regulation?

The public said no — so why is the Tribe being asked?

The CRC was established as a way for Clallam County citizens to directly shape their government. But rather than heed the public’s clear opposition, the Water Steward Subcommittee reached out to the Dungeness River Management Team (DRMT) — a joint body chaired by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s Natural Resources Director Hansi Hals, which also includes County Commissioner Mark Ozias.

The DRMT responded by offering its 2022 Dungeness Water Resources Planning Recommendations, along with an extensive technical appendix. These documents were developed by a DRMT committee heavily populated by tribal officials and government planners. Many of the recommendations, while dressed in scientific language, open the door to future restrictions on rural residents — including those not applicable to the Tribe itself due to its sovereign status.

Some key excerpts:

From Recommendation 6.1:

“An effort should be undertaken to assess the current status of groundwater aquifer levels… and implement continuous, automated water level monitoring and reporting.”

“A revised (current) water budget… should include the relationship between aquifer levels, precipitation… imported/exported water, discharge to salt water, and withdrawals.”

From Recommendation 6.4:

“Updated estimates of future water demand (e.g., at 5, 20, 50 years) should be prepared for review.”

“Metering records should be aggregated and analyzed to determine the current volume of water used per dwelling and/or household…”

From the Appendix on aquifer modeling:

“Live by the model, die by the model.”

This phrase, used by Ann Soule during the development of the Dungeness Water Rule, refers to the idea that even if the science is flawed, the policy will be based on it anyway.

While these may sound like technical goals, they come with real-world consequences. Models like these have already been used to justify well restrictions, metering requirements, and mitigation fees in the Dungeness watershed.

And as one DRMT member put it:

“When ag lands convert to residential… we place other pressures on the landscape (e.g., impervious surfaces).”

“With our water laws, irrigation does not change regardless of this conversion. I can understand ag lands needing large volumes of river water… but I do not understand or agree with large volumes of river water keeping new lawns green in August.”

Those kinds of value judgments — whether about golf courses, farms, or private wells — are exactly what many residents don’t want built into county law.

Sovereignty without accountability?

Perhaps the most concerning aspect is this: the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, as a sovereign nation, is not subject to any of the county regulations that may emerge from these studies or charter amendments. And yet, tribal officials are playing a central role in shaping them.

That’s not conspiracy — it’s policy. As the documents make clear, tribal staff are among the most active participants in the DRMT’s technical group, and tribal priorities such as riparian restoration, stream temperature modeling, and climate-driven growth projections feature heavily in the recommendations.

From the DRMT summary itself:

“Climate change, coupled with the desirability of the Olympic Peninsula as a safe haven against extreme climate impacts, is likely to induce increased development… Future water resources planning… will depend on the most up-to-date growth projections.”

If those “growth projections” are used to limit land use, require mitigation, or impose fees — rural Clallam residents will feel the impact. The Tribe will not.

The Charter belongs to the people — not to the DRMT

The Water Steward proposal is not just about water — it’s about who decides. The Clallam County Charter was never intended to be shaped by back-channel discussions with sovereign nations or unelected bureaucrats.

And yet here we are, with the CRC choosing to bypass its own public poll, and instead seeking direction from the DRMT — a body chaired by the Tribe alongside the County Commissioner whose campaign the Tribe funded.

This is not how democracy is supposed to work.

The bigger picture

It’s no secret that water in the Dungeness Basin is a complex and sometimes contentious issue. But that’s all the more reason for the CRC to stick to its mission: to listen to the people of Clallam County, not outsource their charter to outside interests.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with gathering technical input. But when public opposition is this strong, and the response is to double down on backdoor consultations with agencies and tribes, it raises serious concerns about who the CRC really serves.

Water may be a shared resource — but representation in government is not. If the Charter Review Commission continues to ignore the people who empowered it in the first place, it may find itself answering not just to frustrated voters, but to the question: Who’s really writing the rules in Clallam County?

Do you have a comment for the Charter Review Commission? Email it to the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov and specify “CRC.”