Fifty years of harm reduction: Where's the progress?

Half a century in, Peninsula Behavioral Health doesn't know how to measure success

After five decades and millions in taxpayer funding, has Peninsula Behavioral Health actually improved addiction and mental health outcomes in Clallam County? CEO Wendy Sisk says their harm reduction model isn't about enabling—but when asked to define success, she couldn't. Meanwhile, a fatal assault in Sequim went unmentioned by city leaders. With luxury housing projects, spiraling costs, and no clear accountability, is harm being reduced, or just spread evenly throughout the community?

At the Clallam County Commissioners’ work session on Monday, Peninsula Behavioral Health (PBH) CEO Wendy Sisk gave an update on the organization’s work. Founded in 1971 with just three staff, PBH now employs more than 140 people. After more than 50 years of effort and substantial growth, the question remains: has the problem gotten better?

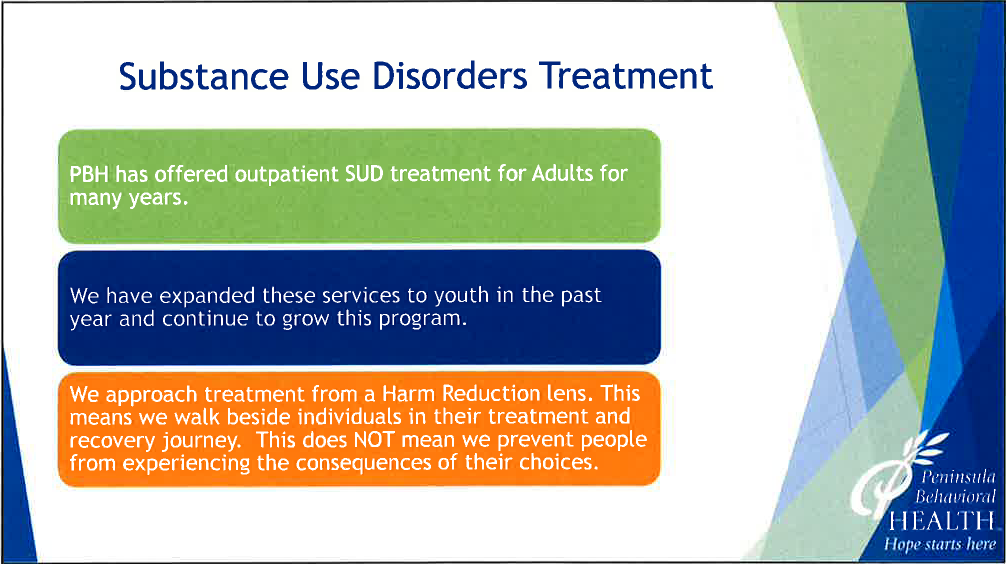

Sisk, who has been with PBH for 22 years, emphasized that the organization follows a harm reduction model—something she said has been foundational since the very beginning.

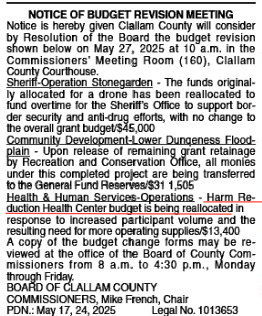

It's a model fully embraced by Clallam County—so much so that the budget is being revised to allocate even more taxpayer dollars toward purchasing needles, meth pipes, crack pipe cleaning kits, and “boofing” supplies designed for drug users to administer drugs rectally.

Walking beside, not directing

“And I just want to take a moment to say that that doesn't mean we enable people. That doesn’t mean that we support people using,” Sisk explained. “It means our job in all things is to walk beside people on their journey, and it is to help people look at the consequences of the choices that they’re making.”

She stressed that PBH doesn’t make choices for clients, but rather encourages them to reflect on their own outcomes, and she used Commissioner French as an example. “Mike, so that’s what you did, is that really the outcome that you were looking for?” she said, paraphrasing a typical client interaction. Sisk emphasized that harm reduction “does not mean preventing them from experiencing the consequences of the choices that they make.”

She also addressed misconceptions explaining that harm reduction — passing out free needles, meth pipes, and crack pipe cleaning kits — is helping people continue to use. Instead, she said that consequences “help shape behavior change.”

Dodging the success question

When Commissioner Randy Johnson, who holds a master’s degree from Harvard Business School, asked how PBH defines and tracks success, Sisk responded with a question of her own: “What do you mean by success, Randy?”

Johnson proposed a reasonable definition: functioning in society while sober and self-reliant. “You can measure it a lot of different ways,” he added.

Sisk replied, “Well, let’s talk for a minute about what success means. It depends, right?” She noted that not everyone ends up “married and employed with a college degree and 3.4 kids.” For her, success is defined individually, based on what the person sitting across from her wants for themselves.

But Johnson’s point was broader. He wasn’t asking how each individual defines their own success. He was asking how PBH, as a taxpayer-funded organization, defines success for itself. How is the public to know whether PBH is succeeding in helping people? What metrics are used? The question was never answered directly.

Sisk eventually acknowledged, “We aren’t always successful,” noting again that PBH cannot control people’s decisions—only offer tools and opportunities. But for taxpayers, success might reasonably mean helping people recover from addiction, find employment, rebuild relationships, and rejoin society as contributing, independent members.

Success for whom?

What does success look like from other perspectives?

For a PBH client, this might mean being released from jail after multiple arrests and securing a $350,000 permanent supportive housing unit at PBH’s new luxury homeless apartment complex—with water views, air conditioning, a dishwasher, and even a dog washing sink. Knowing that substance use is discouraged but tolerated, and that just a few blocks away, free pizza, needles, and “boofing kits” are available—as long as you bring your own drugs.

For Wendy Sisk, success might look like earning a $250,967 annual salary in a county where the median income is barely a fifth of that—while overseeing an organization that received over $4 million in county taxpayer funding last year. And when Commissioner Johnson, who earns less than half her salary, asks for measurable outcomes after approving those funds, and Sisk is allowed to sidestep the question without a single follow-up—well, that’s a kind of success, too.

And for someone like Aaron Fisher—who earlier this month allegedly assaulted an elderly man during Sequim’s Irrigation Festival, leading to the man’s death—success might mean being quietly released from jail. With the police asking witnesses to step forward, and local media refusing to cover the story, there’s no public reckoning. Fisher has a long history of arrests and apparent drug use, according to social media. Is this what the success of harm reduction looks like—ensuring people stay alive just long enough to keep using, even if it costs the community dearly?

Silence in Sequim

The city council in Sequim, where the assault occurred, hasn’t acknowledged the incident publicly. At Monday night’s meeting, Councilmember Dan Butler instead reported on the Clallam County Homelessness Task Force.

He mentioned a tragedy—but not the death of a community member. The “tragedy,” in his words, was homelessness. He spoke about how housing is the key to sustainable employment, recovery, and mental health.

This is the prevailing view: that the solution to complex social issues lies solely in housing. That if you build it, people will recover. But is that happening?

“Housing First” has become a mantra. The idea is to provide shelter before addressing addiction or mental health needs. But what if the opposite is true? What if treating root causes—addiction, trauma, and mental illness—must come first? Otherwise, are we simply warehousing dysfunction at public expense?

A 40-second update on $12.75 million

PBH’s latest housing project, the 36-unit Northview complex, is projected to cost nearly $13 million. Sisk briefly addressed it in her 55-minute presentation. “I didn’t realize how many things change when you’re building from the ground up,” she said. That slide, arguably the most significant in terms of taxpayer impact, received just 40 seconds of discussion. No one asked if the project was on budget. No one asked how PBH is stewarding public funds.

It’s worth remembering what happened last time. PBH’s previous housing initiative, Dawn View Court, was supposed to convert a 25-unit Port Angeles motel into supportive housing for $3.5 million. But mismanagement and unforeseen problems—including water left running during a freeze, leading to burst pipes, flooded units, and stolen copper—pushed the final cost to $4.8 million, a 37% overrun.

Avoiding accountability and hard questions

Back in Sequim, no one on the city council mentioned the fatal assault during the public meeting. No acknowledgment. No moment of silence. Just a continued focus on the broader “tragedy” of homelessness—without any public reflection on how our policies may be contributing to public harm.

Where is the hope?

We know that businesses bring jobs. Jobs bring purpose and structure. That builds self-worth. That reduces drug use. That reduces mental illness. But when our focus is on managing symptoms with no measurable goals, no accountability, and no clear definition of success, we risk enabling long-term dysfunction—not recovery.

We can—and must—do better.

Last Sunday, readers were asked if their bluff-front property was at risk, would they feel pressured to sell if it were labeled “high threat” in an erosion report. Out of 158 votes:

37% said, “Yes”

14% said, “No”

49% said, “I’d fight it”

Harm Reduction does not work, it has never worked and we should have learned this lesson from Holland who was the first to try it 40 years ago. “ It didn’t work”. Why do these so called community leaders who have never been addicted to anything but power, think they know best?

This tax payer funded program is tearing our communities up little by little.

What a joke when the leader cannot define success but wants millions of dollars more to continue a defunct program.

The more services that we offer like this, the more derelicts come to our area and our communities look like shit. We the citizens pay for it not just through money but our lives and our property. It’s just not worth it.

I know these people think they are doing the right thing but when you have no accountability you create a problem that only compounds. Nothing will change unless people face consequences for their actions. This starts at the top with our governor and runs downhill. With our current political climate, I'm sorry to say that the likelihood of positive change is slim to none.