As bluffs crumble along Clallam County’s coast, a powerful force is quietly moving in—not the ocean, but the Jamestown Tribe. Armed with erosion models, funding partners, and a strategy that openly banks on landowner fear, the Tribe’s conservation plan looks less like restoration and more like a calculated land acquisition campaign. Read how desperation is being turned into opportunity—and who really stands to gain as the shoreline recedes.

What happens when science, fear, and political influence collide on private property lines?

Along Clallam County’s shoreline near Agnew, an unsettling trend is unfolding. The Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, citing environmental concerns, has developed a detailed and technical document that might look like coastal restoration policy—but reads, to some landowners, like a playbook for targeted land acquisition.

The 2016 Dungeness Drift Cell Parcel Prioritization and Conservation Strategy, authored by the Tribe, identifies private bluff-top parcels not just for conservation, but for acquisition—prioritized, according to their own words, by a landowner’s fear and lack of alternatives. And that’s not speculation. It’s spelled out in black and white:

“Fear may turn to desperation, especially where the landowner does not own sufficient property to move the structure back from the bluff.”

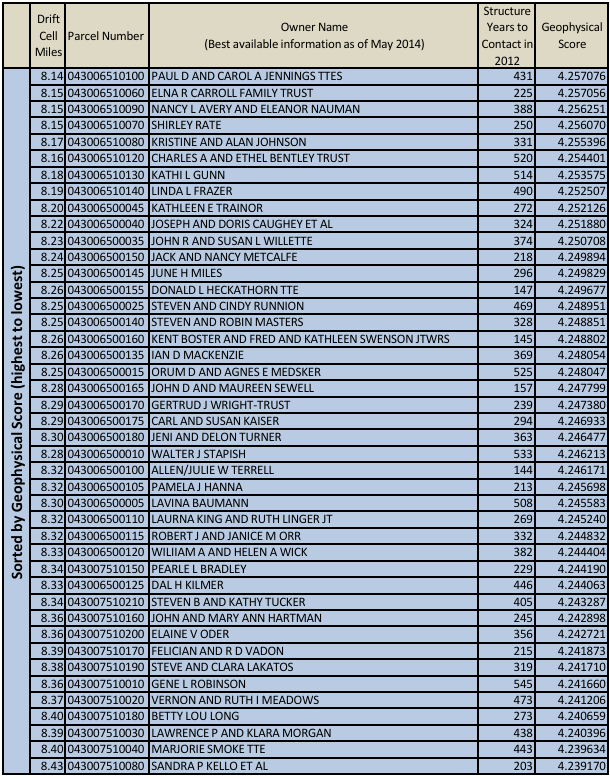

The document lays out a matrix of criteria used to identify which landowners are most likely to panic—and therefore, most likely to sell. Properties are categorized based on how soon bluff erosion is expected to reach a home (“Years to Contact”), whether the homeowner has room to retreat from the bluff, and the density of surrounding development. Together, these factors are synthesized into what the Tribe bluntly calls an “Immediacy of Threat” score.

“Structure owners with a low Years to Contact value and no relocation potential are likely to be the most fearful bluff property owners.”

Fear. Desperation. No options. Then, enter the Tribe with offers of “fee-simple purchases,” relocation incentives, or conservation easements—often backed by public funding and governmental partnerships.

A threat becomes an opportunity

According to the strategy document, early efforts will concentrate on the stretch of bluff between Morse Creek and the Dungeness Spit. These are high-value properties, some with million-dollar views—until the bluff erodes or a government-backed “conservation” project makes them functionally worthless. It’s here that the Tribe plans to act first:

“Starting with parcels identified as Priority 1, landowner willingness will be assessed and funding will be sought to implement conservation measures.”

But is “landowner willingness” really willingness when it’s driven by the threat of losing everything? When “desperation” becomes an input in the Tribe’s own threat matrix?

Weaponizing appraisals and public power

The strategy goes further. It proposes ranking parcels by “Cost Effectiveness,” dividing shoreline length by assessed property value. This metric is used to determine which parcels offer the most shoreline for the least money.

In essence: who’s scared, and who’s cheap.

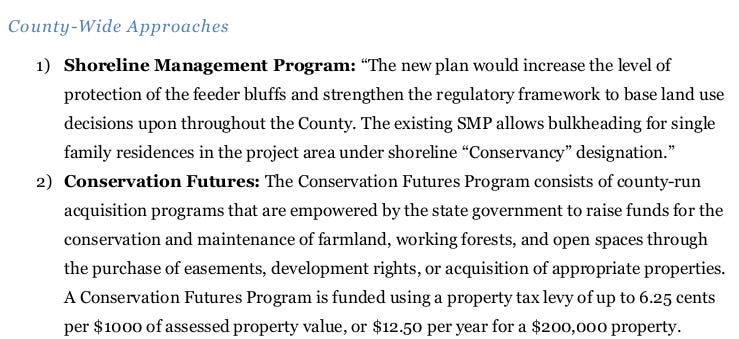

The Tribe also doesn’t plan to go it alone. Their document outlines a collaboration strategy with public agencies like Clallam County, the Department of Fish and Wildlife, and local land trusts to secure funding and easements—many of which may be held by third-party nonprofits to keep the Tribe’s hands clean and political scrutiny at a distance.

And in places like 3 Crabs Road, where property owners face looming eviction, and the Lower Dungeness Floodplain Restoration Project, where the North Olympic Land Trust played a role in the Tribe’s attempted seizure of Towne Road, residents are already witnessing these tactics in action and have begun to push back.

Is this conservation or coercion?

Yes, bluff erosion is real, and so is the need for environmental stewardship. But when the plan explicitly targets vulnerable homeowners—those who are afraid, financially limited, or isolated—it starts to feel less like conservation and more like coercion.

The Jamestown Tribe, a sovereign government with considerable resources and influence, is positioning itself to shape the future of this coastline—parcel by parcel, fear by fear. And unless Clallam County residents start asking harder questions, they may find themselves boxed in by a conservation policy that doesn’t conserve their rights.

If you’re a bluff property owner in Clallam County, especially along the Agnew coastline, the clock may be ticking—not just on erosion, but on ownership itself.

Last Sunday, readers were asked what the County’s top priority in addressing the opioid crisis should be. Of 207 votes:

60% said, “Enforcing laws / reduce drug access”

36% said, “Drug-free recovery and treatment”

3% said, “Increasing access to MAT (Medically Assisted Treatment)”

1% said, “Increasing harm reduction services”

Please keep up your excellent reporting.

This year’s budget proposal includes deeply concerning cuts that suggest a return to an “Indian Termination Era” mentality. While a few programs, like Head Start and drinking water infrastructure, see modest gains, the overall budget reflects a significant rollback of critical resources for Tribal communities.

Key Proposed Cuts to Indian Country:

26.2% cut to HHS, affecting programs critical to health outcomes in Indian Country.

$1.7 billion cut from Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), leaving just $6 billion for “priority activities.”

Elimination of the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP).

$1 billion cut to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), including funding for Tribal Opioid Response.

$674 million cut from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, though the proposal claims it won’t impact recipients.

$770 million cut from the Community Services Block Grant program.

30.5% cut to the Department of the Interior.

Nearly $1 billion cut from Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).

$617 million cut from BIA programs supporting Tribal self-governance.

$107 million cut from BIA Public Safety and Justice programs.

$187 million cut from the Bureau of Indian Education construction account.

Elimination of discretionary awards under Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI).

Elimination of competitive NAHASDA grants.

Cuts to Community Development Block Grants (CDBG

I'm not sure how cuts in these programs will affect the Tribes ability for land acquisitions, but there seems to be a scramble for funding right now.