Commissioner Mike French’s stance on legal precedent appears firm—until you look closer. While he cites case law to justify inequitable ticket pricing at Sequim schools, his past positions suggest a more flexible approach to legal principles. Why does he champion strict adherence to the law in some cases but dismiss it in others? This article examines the inconsistencies in his approach to equity and policy.

The Clallam County Commissioners frequently write letters of support for various projects and initiatives. Recently, they supported the Field Arts & Events Hall's request for an additional $4 million in taxpayer funding and endorsed the Sequim School District’s ballot measures—despite one commissioner’s staggering $100 million miscalculation in a bond proposal. Previously, they backed the Jamestown Tribe’s proposed roundabout on Highway 101 in Blyn.

Following the discovery that the Sequim School District was calculating ticket prices based on tribal status, the commissioners were asked whether they would consider writing a letter advocating for the elimination of this race-based pricing policy. French was the only one to respond.

“I would not support that request. For five decades, it’s been settled law that tribal preference is not race-based, it’s a political preference (Morton v Mancari). You’re free to criticize the Sequim School District for having that preference in ticket prices, but in my limited understanding, it is not a race-based preference according to US law.”

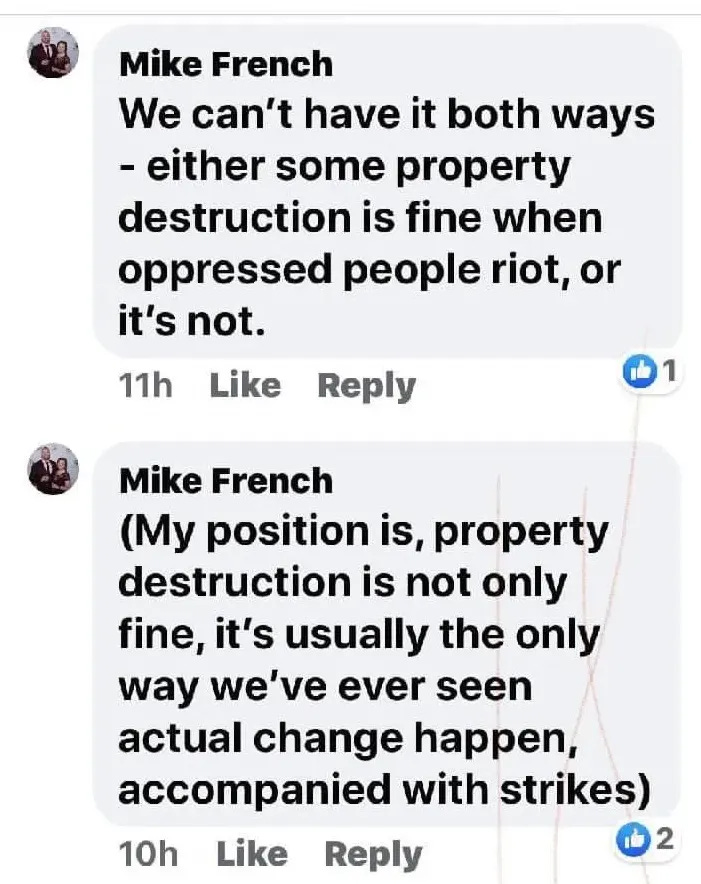

French’s sudden commitment to legal precedent and careful distinctions between political and racial classifications stands in stark contrast to his past actions. When it comes to issues he supports—such as property destruction in the name of social progress—he has openly dismissed the importance of law and order. In a previous statement, French condoned vandalism as a necessary tool for achieving change, suggesting that unlawful actions can be justified when the cause is deemed righteous.

Morton v. Mancari: A convenient distinction

Morton v. Mancari (1974) was a U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld a law giving hiring preference to Native Americans for jobs in the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Court ruled that this preference was not racial discrimination but rather a political distinction because Tribes are sovereign political entities, not racial groups. This means that laws benefiting Native Americans are based on their political status as members of federally recognized Tribes, not simply their ancestry.

However, the criteria for Jamestown tribal membership—like that of most Tribes—are based on ancestry and bloodline. To be recognized as a member of the Jamestown Tribe, an individual must demonstrate lineal descent from someone listed on the base roll (which intentionally excluded women and children) or meet a specific blood quantum requirement. While Tribes are indeed political entities, membership is determined by ancestry and genetic heritage.

The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines race as “any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry.” By that standard, does the distinction between racial and political classifications truly hold up?

Justification or deflection?

Since Commissioner French was the only one to respond to the initial request, he was further asked if he would consider writing a letter urging the Sequim School District to end its politically based ticket pricing system in the name of equity. He replied:

“No, I would not. I support public school districts in their attempts to have positive relationships with sovereign tribes within their school district boundaries.

“A good primer on the troubled history between tribes and American education can be found in the concurring opinion authored by Justice Neil Gorsuch (appointed by President Donald Trump in early 2017) of the case Haaland v Brackeen, decided in 2023. Link here: Haaland v. Brackeen | 599 U.S. ___ (2023) | Justia U.S. Supreme Court Center.”

Haaland v. Brackeen was a U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA), a law designed to keep Native American children within their tribal communities when placed in foster care or adoption. It reaffirmed the principle that tribal affiliation is a political classification rather than a racial one.

Critics of ICWA argue that it creates an unequal system by prioritizing tribal affiliation over the “best interest” of individual children. However, supporters counter that ICWA corrects historical injustices and respects Tribes' political status rather than imposing racial preferences.

So, what does Haaland v. Brackeen have to do with discounted sports tickets? French’s reference to the case suggests that any policies affecting Native communities should be assessed through the lens of tribal sovereignty rather than racial equity. But does a $2 ticket discount meaningfully address historic injustices and systemic inequities faced by Native American students? Does this policy truly work toward healing past harms, or does it merely reinforce differences among students rather than bridging them?

Selective application of principles

If equity is truly the goal, is this the best way to achieve it? And more importantly, why is Commissioner French so selective in deciding when legal precedent should be respected? When it suits his agenda, the law is flexible—vandalism can be justified, and rules can be bent. But when faced with a question of fairness that challenges his worldview, he suddenly becomes a strict adherent to legal doctrine.

This inconsistency raises larger questions about the role of government officials in shaping policy. If fairness and justice are truly guiding principles, they should be applied consistently—not merely when they align with personal beliefs.

Polling: What do you think?

Last Equitable Wednesday, subscribers were asked if the Sequim School District’s equity initiatives are effective in promoting fairness for all students. Of 237 votes:

90% voted “no.”

4% voted “yes.”

6% voted “not sure.”

Beyond ticket prices, similar preferential policies exist elsewhere. For example, Olypen, an internet service provider in Sequim and Port Angeles, has previously offered a 30% discount to tribal citizens for computer repair and support services.

Why do left-of-center politicians like French make stupid statements regarding destruction of private property, and then in the next breath decry the marked increase in legal firearm sales? Do they simply not understand cause and effect?

As I told Ozias last year, "Your constituents aren't stupid."

So, based on French's publicly affirmed worldview as to how political change occurs, setting fire to his house is an acceptable act of protest against his incompetence and predilection for legal sophistry?

And people like him actually think anyone right of center is a menace to democratic government?

French is a tool and a child.