The long-promised Simdars Road Interchange was supposed to bring safer access and economic opportunity to Sequim’s east side—but now it’s delayed until at least 2031. While rural drivers wait, and gas prices rise again, millions from Washington’s Climate Commitment Act are funding EV stations, planning conferences, and grant programs elsewhere. As fuel surcharges hit working families hardest, Clallam County residents are questioning whether climate revenue is truly serving the communities who need it most.

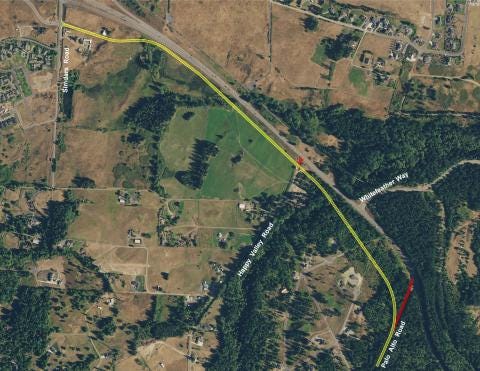

In 2023, the long-anticipated Simdars Road Interchange appeared to be gaining momentum. The state project would open eastbound access from Highway 101 into the east end of Sequim and provide much-needed frontage road connections to Happy Valley and Palo Alto Roads—two key rural corridors with limited safe access points.

Many saw the interchange as a way to improve safety, relieve congestion, and stimulate economic development on Sequim’s east side. But funding now appears to be on hold.

As the Sequim Gazette reported, state lawmakers have delayed full funding for the project until at least 2031, citing a transportation budget shortfall. Representative Steve Tharinger (D-Port Townsend) said, “The challenge is the funding model for transportation, which is a gas tax, a depleting source of revenue.”

This came despite the defeat of Initiative 2117, a statewide ballot measure that would have repealed the Climate Commitment Act (CCA)—Washington’s cap-and-invest carbon pricing program. At the time, Representative Tharinger had warned that passage of I-2117 might jeopardize Simdars funding.

But voters rejected the initiative, and the CCA remained intact—generating hundreds of millions in carbon revenue. Even so, Simdars was shelved.

For some in Clallam County, this sequence of events has raised difficult questions: If the state is collecting so much climate revenue, why aren’t rural infrastructure priorities like Simdars getting funded?

Where the CCA dollars are going

The Climate Commitment Act—in effect since 2023—adds costs to carbon-emitting fuels like gasoline and diesel through quarterly auctions of carbon allowances. While these costs are not itemized at the pump, economists estimate they add 20 to 50 cents per gallon, depending on market conditions.

That revenue is then redistributed through state programs. In 2024, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe received:

$727,500 from the Tribal Climate Resilience Grant Program

A share of $52 million in CCA tribal allocations

And an estimated $1.6 million to install 27 electric vehicle charging stations across seven Tribal facilities.

In a 2024 newsletter, the Tribe credited CCA funding for their EV infrastructure expansion. In 2025, they further reported their support for Senate Bill 6058, which aims to link Washington’s carbon market with those of California and Quebec—potentially increasing revenue from cap-and-trade auctions.

Meanwhile, projects like Simdars Road—which would benefit the general public—remain unfunded.

Closed-door planning on tribal land

Climate Commitment Act funds have also supported planning events, including a regional climate conference hosted by the North Olympic Development Council (NODC) at the 7 Cedars Casino, which is owned and operated by the Jamestown Tribe.

The event brought together agency staff and select stakeholders to discuss the climate elements of local Comprehensive and Hazard Mitigation Plans. While the purpose was to “help shape the climate component of area comprehensive and Hazard Mitigation Plans,” the public was not invited, and the venue was outside the reach of typical Clallam County government meeting norms.

The optics raise concerns for some residents: public dollars collected through fuel surcharges were used to fund a closed-door planning session on sovereign land, with limited local transparency.

Fuel, freight, and affordability

The Climate Commitment Act, combined with Washington’s fuel excise taxes, contributes to rising costs for construction, transportation, and living expenses—particularly in rural areas where driving is essential and building materials are delivered by truck.

On July 1, 2025, Washington’s gas tax rises by another 6 cents, bringing the total to 55.4¢ per gallon. Under SB 5801, it will increase by an additional 2% annually, tied to inflation, starting in 2026.

That hits hardest in places like Clallam County, where commuting distances are long, housing is scarce, and wages are modest. The added cost of every gallon translates into higher prices for homebuilding, groceries, and goods.

Meanwhile, tribal gas stations, including those operated by the Jamestown and Lower Elwha Tribes, retain 75% of the gas tax under long-standing agreements. That means for every 6-cent increase, 4.5 cents per gallon stays with the Tribe—a legal and negotiated outcome, but one that illustrates how state policy affects different communities in different ways.

The road ahead

Washington’s climate policies are designed to address global challenges—reducing emissions, investing in clean energy, and preparing for climate risks. But their success may depend on ensuring that rural areas are not left behind, and that revenue collected locally results in visible local benefits.

Projects like Simdars are more than asphalt—they’re lifelines for working families, small businesses, and emergency response.

As the state prepares for another round of carbon auctions, many in Clallam County are watching closely, asking: If the money is there, why isn’t it coming here?