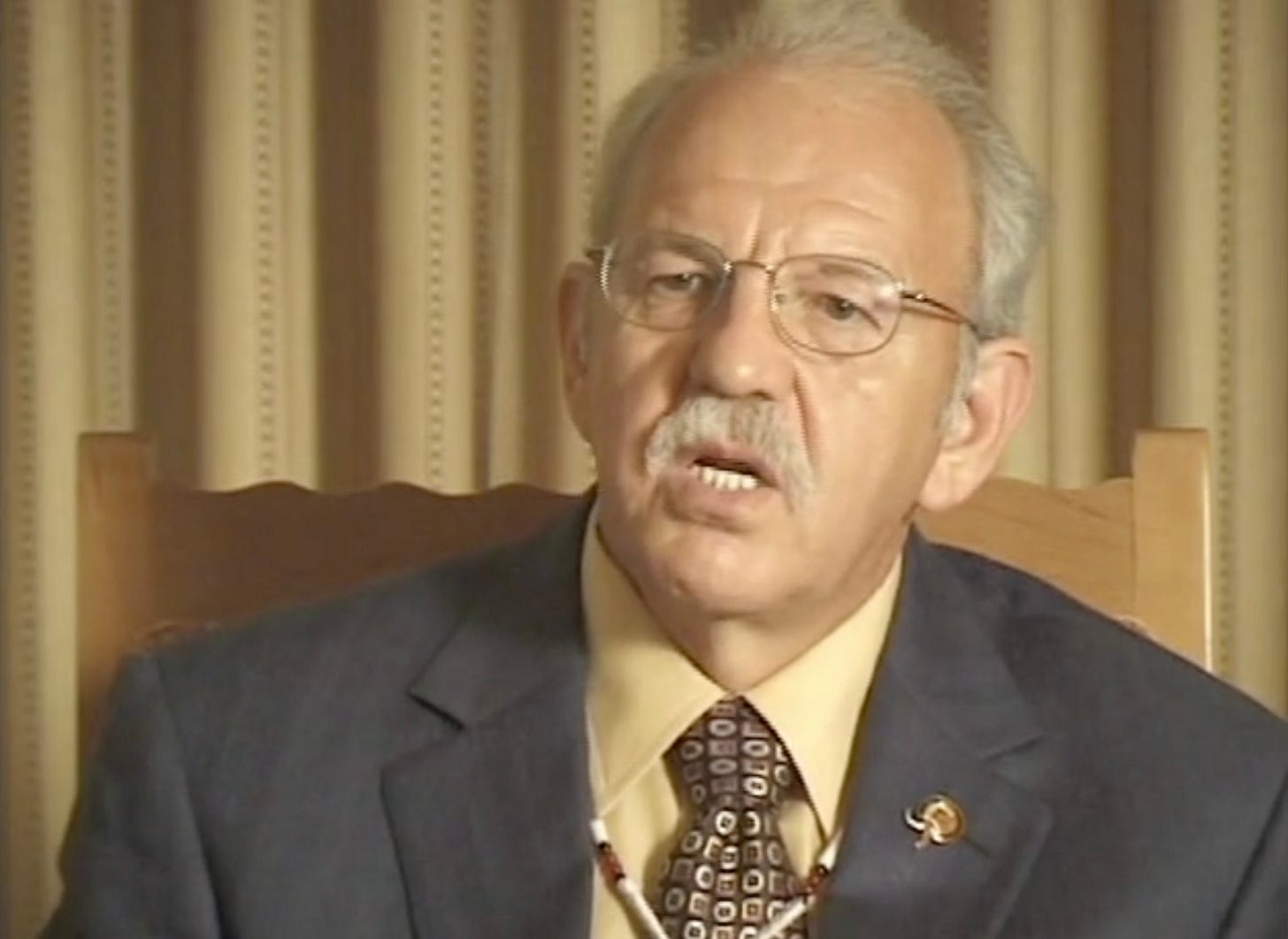

Ron Allen, Then and Now

A 23-year-old interview that explains today's power structure in Clallam County

In 2003, Jamestown S’Klallam Chairman Ron Allen sat for a landmark oral-history interview reflecting on sovereignty, self-determination, and the responsibilities of tribal governance. Twenty-three years later, Allen is the CEO of the Jamestown Corporation, the second-largest employer in Clallam County and arguably the most influential political figure in local government. Revisiting his own words provides rare clarity — and raises uncomfortable questions.

A Look Back That Explains the Present

Produced by the Institute for Tribal Government at Portland State University, the Great Tribal Leaders of Modern Times interview series was designed to preserve the oral histories of influential Native leaders. Ron Allen’s interview, conducted in June 2003, is candid, strategic, and revealing.

At the time, Allen was already a veteran tribal chairman, having assumed leadership in 1977 and overseen the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe’s restoration to federal recognition in 1981. He would go on to serve simultaneously as chairman and executive director, overseeing education, health, housing, economic development, natural resource management, and cultural affairs.

Today, Allen remains chairman — and is also CEO of the Jamestown Corporation, whose reach now extends deep into Clallam County’s economy, land use, and political decision-making.

Revisiting this interview is not about nostalgia. It is about understanding how today’s reality was intentionally built.

From “Wild Child” to Power Broker

Born in Sequim in 1947, Allen describes himself as a “wild child,” raised in a rural household by parents with strong political opinions.

“They were very avid Democrats… as loyal to the Democrat Party as you could possibly get. And when I went into college and I ended up shifting more into a Republican philosophical perspective, my mother had the hardest time with that.”

He attended Peninsula College and earned a BA in political science from the University of Washington — training that would later show clearly in his methodical approach to governance and politics.

Allen is open about his mixed heritage — roughly one-quarter S’Klallam and three-quarters European — and recounts how his fair skin often led people to question his identity.

“People were wondering about me… ‘Who’s this White guy out here? Is he really Indian?’”

He also recounts receiving a 4-F draft classification during Vietnam, avoiding military service — a decision he reflects on without apology.

Federal Recognition as the Inflection Point

One of the most consequential moments in the interview comes when Allen describes how a missing tribal ID card during a basketball tournament exposed a deeper truth:

“The BIA has decided to no longer recognize our tribe… and that’s when my whole career with the tribe emerged.”

From that moment forward, Allen became deeply involved in the federal recognition process, ultimately succeeding in 1981. That victory unlocked not just sovereignty — but leverage.

Why Jamestown Isn’t in Jamestown

Allen explains why the tribal headquarters ended up in Blyn, east of Sequim, rather than Jamestown, north of Sequim:

“Jamestown was designated a flood plain zone so you couldn’t spend federal dollars there.”

That decision — driven by federal funding rules — would later prove pivotal as the tribe acquired land, expanded enterprises, and built infrastructure far beyond its historic footprint.

When the County Finally Paid Attention

Allen is candid about how little interest Clallam County officials initially showed the Jamestown Tribe:

“County commissioners, they didn’t pay much attention to us at all… they weren’t going to pay attention to us.”

That changed after the tribe’s 1985 land settlement — and especially after the fireworks stand and later casino drew attention.

“That annoyed them… they had no control over what we did on our property.”

Today, the contrast is stark. County commissioners now openly describe the Jamestown Tribe as their most important partner, regularly aligning county policy with tribal priorities — including land acquisition and land-use decisions.

Economic Strategy — and Resentment

Allen lays out his economic philosophy plainly:

“Go slow, go after capital-intensive businesses… then step off of them to go after labor-intensive businesses.”

He acknowledges that success brought backlash:

“People started throwing rocks at us because of jealousy and envy.”

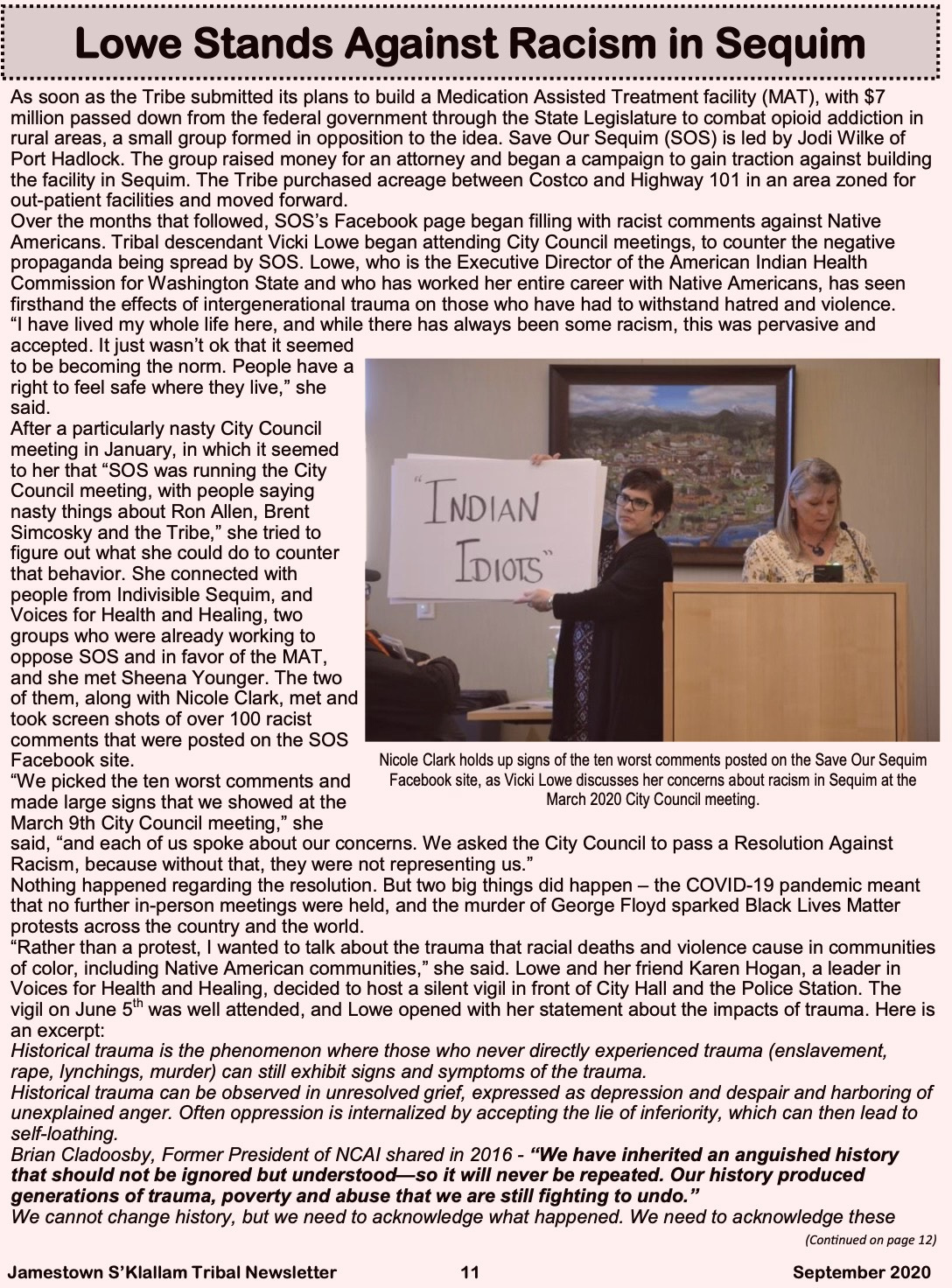

That framing — criticism as envy or racism — is notable given recent events, including Allen publicly referring to concerned Clallam County residents as whiners and complainers for questioning Jamestown-aligned policies.

Fisheries, Shellfish, and Exclusive Areas

Allen explains that Boldt was only the beginning:

“The Bolt decision dealt with only the fin fish… it did not deal with shellfish.”

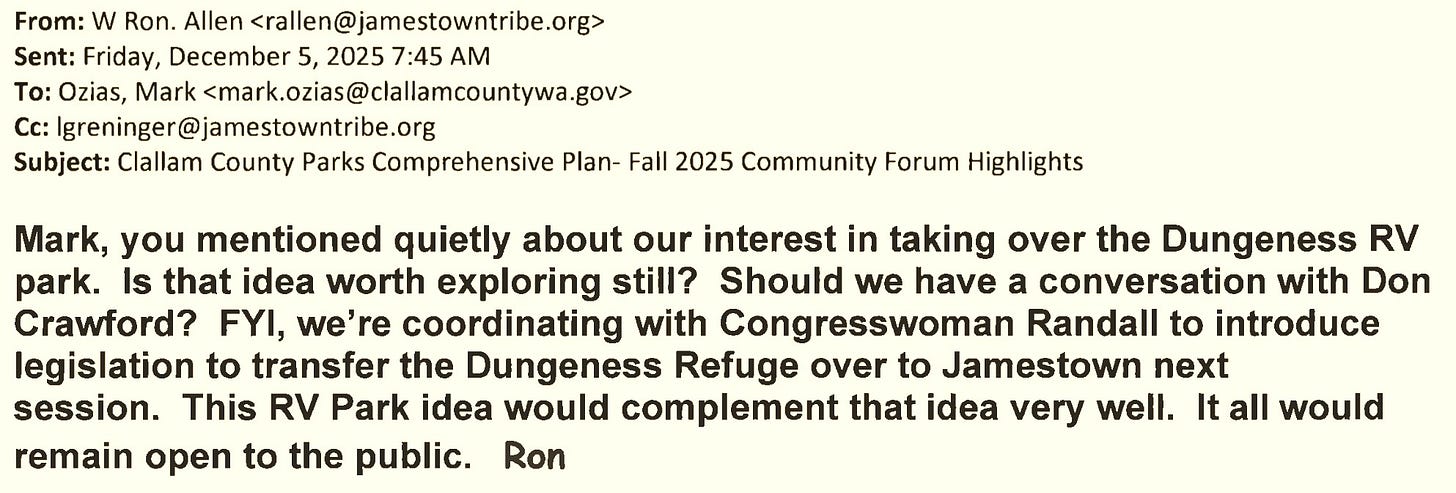

Through later court rulings, tribes secured rights to 50 percent of shellfish harvests — a ruling that now underpins Jamestown’s rapid expansion of commercial shellfish operations inside the Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge, even as the Tribe simultaneously works with Congress to obtain federal control of the refuge and with Commissioner Mark Ozias to take over management of the Dungeness Recreation Area — effectively consolidating regulatory, commercial, and political control over the county’s most prized public coastline.

Allen himself describes the area inside Dungeness Spit as “very tense” — even in 2003.

Politics, Money, and Influence

Perhaps the most revealing portion of the interview concerns political funding.

Allen openly recounts how tribes mobilized money and votes to defeat Senator Slade Gorton and elect Maria Cantwell:

“We started generating money for her… we got our people registered… we chalked it up as an Indian victory, no question about it.”

He describes this as a turning point — tribes becoming sophisticated political players, leveraging economic success into electoral power.

That strategy did not stop at the federal level.

Today, Jamestown Corporation campaign contributions and endorsements play a decisive role in local races — particularly county commissioner elections — raising unavoidable questions about independence, accountability, and influence.

Words Versus Actions on Accountability

One quote from 2003 stands out in light of recent history:

“If you make a mistake, then you own up to it. It’s your fault, nobody else’s.”

That statement sits uneasily beside the Jamestown Corporation’s intentional early breach of the Dungeness River dike, an action that tribal staff themselves warned could cause mass casualties. The breach closed Towne Road for two years, and cost taxpayers millions — with no clear acceptance of responsibility matching Allen’s stated philosophy.

“News helicopters would circle the devastation and speculate on the number of dead. The County, Tribe, and the Corps would be embroiled in wrongful death suits for years or decades.” — The Jamestown Corporation’s Habitat Program Manager, warning of potential devestation from removing the dike

Shaping Minds, Shaping Narratives

Allen is explicit about long-term strategy:

“You change a society… at the younger level. You use the media… every form of media.”

Education, curriculum influence, messaging, and strategic outreach are not incidental — they are central. The Jamestown Tribe is actively promoting curriculum proposals for adoption within the Sequim School District.

Why This Interview Matters Now

This 2003 interview is not a relic. It is a blueprint.

Ron Allen’s own words explain how Jamestown became powerful, how political influence was intentionally built, and how criticism has long been framed as hostility or racism rather than legitimate civic concern.

Understanding this history does not require hostility toward tribal sovereignty. It requires honesty.

And it requires asking whether the standards Allen articulated for governance — accountability, transparency, ownership of mistakes — are being applied today.

Readers are strongly encouraged to watch the full interview or read the transcript.

It is rare to hear a local power structure explain itself so clearly — in its own words.

The commissioners did not answer yesterday's questions about holding a town hall to discuss the Dungeness Recreation Area. Here is today's question:

Dear Commissioners,

People are concerned about how much influence a single major donor or powerful local interest may have in county decision-making — and about the way critics are sometimes brushed off. What are you doing, specifically, to make sure your communications with major private interests and tribal partners are transparent? Will the public be able to see who you’re meeting with, what’s being discussed, and how those conversations might affect land-use decisions or the county’s tax base?

All three commissioners can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov.

“When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time”- Maya Angelou