Clallam County’s septic crackdown may look like environmental policy—but for many rural residents, it feels like regulated displacement. Who’s really shaping the future of our land and water?

There’s a new newspaper in town. Many Clallam County residents recently received a free copy in the mail. But “free” may be a stretch—it’s funded by taxpayers, and it isn’t quite journalism either. Instead of holding power accountable, it’s written and published by the very government agencies it covers.

The publication is called the Clean Water Herald, produced by Clallam County Environmental Health. This particular issue focuses heavily on septic systems. It also advertises a community meeting scheduled for Thursday, May 29, from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. at the Dungeness River Center (owned and operated by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe) on 1943 W. Hendrickson Road in Sequim.

It’s being hosted by Clallam County, the Jamestown Tribe, and Streamkeepers of Clallam County—a county agency whose teams conduct quarterly water monitoring and manage stream health data. These programs often sound neutral on paper, but they wield significant regulatory power with little public scrutiny.

Also involved is the Clallam Conservation District—technically a county branch of a state agency. It’s known for metering private wells and trenching through private land to pipe irrigation ditches without permission or proper easements, under pressure from tribal legal threats.

Water quality goals and unequal enforcement

The Herald outlines how the PIC program is a joint initiative between Clallam County Environmental Health, the Conservation District, and the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe. Their stated goal is improving water quality in Sequim and Dungeness Bays following shellfish harvesting restrictions due to elevated fecal coliform levels.

That goal aligns with another major tribal project: a 50-acre commercial oyster farm in the Dungeness Bay National Wildlife Refuge. The farm will introduce non-native shellfish species, and its viability depends on strict water quality regulations—many of which apply to homeowners and farmers but not to the Tribe.

According to the newsletter, the PIC program uses "data-driven" assessments to identify pollution sources such as septic system failures and agricultural runoff. The current target is the Matriotti watershed. That’s notable because the Tribe’s 100-acre, award-winning golf course—well-fertilized and watered—straddles Matriotti Creek. Golf courses, while often scenic, are recognized for their environmental footprint: chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and extensive irrigation contribute to nutrient runoff.

Despite these concerns, the Tribe’s golf course remains exempt from county and state environmental regulations because it sits on sovereign land. While rural homeowners are being subjected to stricter septic inspections and costly new requirements, tribal developments continue without the same oversight or constraints.

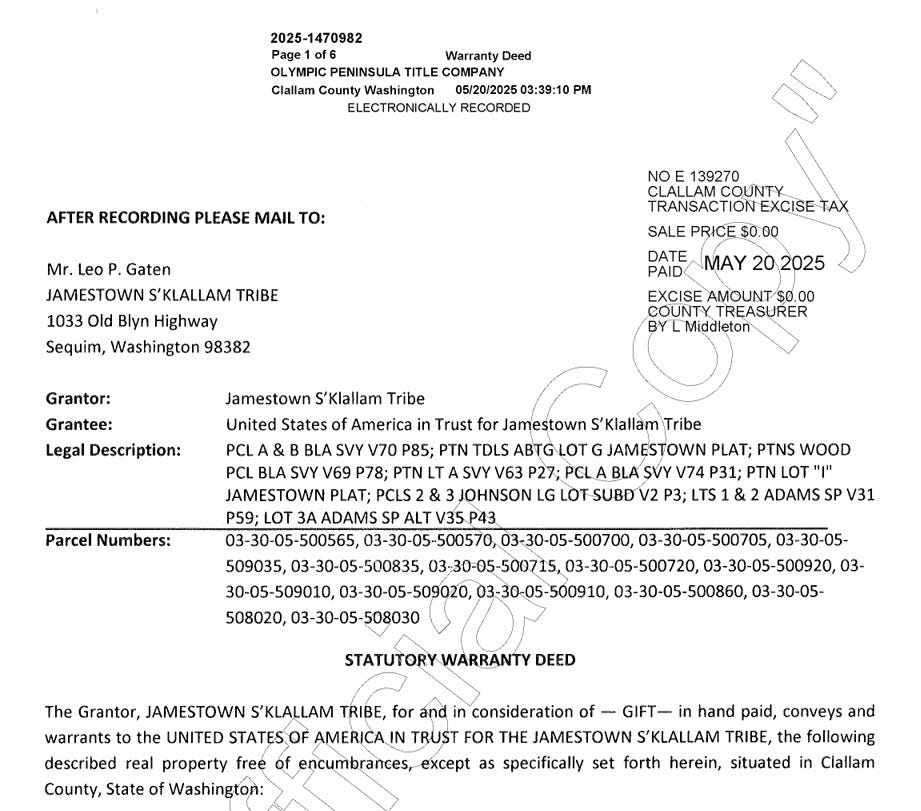

This week, the County received notice that the Jamestown Tribe is moving to place 15 additional parcels into trust. Once transferred, these lands will no longer contribute property taxes that fund essential local services—and they’ll be similarly shielded from the growing web of septic regulations affecting other county residents.

Rising costs and tightening regulations

County Environmental Health staffer Janine Reed gave a presentation to the Board of Health and County Commissioners on April 15 outlining proposed changes to the county code. One notable change: homeowners will no longer be allowed to install their own septic systems if they live within 200 feet of marine water or 100 feet of surface water.

If you're a homeowner, you know labor costs drive most project expenses. Losing the ability to do your own septic work means increased reliance on licensed professionals—driving up costs even further and contributing to the region's worsening housing affordability crisis.

One resident’s struggle

The story of a local property owner, detailed a year ago, underscores the real-world impacts of these policies. Anita Pruvell, a longtime county resident, tried to fix a septic issue on her rental property, but soon faced mounting demands from Clallam County Environmental Health. Janine Reed denied her permit application, claiming that her home couldn’t legally include an Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU), even though both structures were built in the 1920s and had long existed on the same parcel. Pruvell signed a Voluntary Compliance Agreement with the county and made a good-faith effort to meet the requirements—installing a new septic system, decommissioning the old one, and applying for the appropriate permits.

Even after completing these steps, her permit was again denied over a technicality. When she applied for a hardship-based fee waiver, citing IRS documentation showing she had lost money that year, the request was denied. Then came an even more troubling development: Janine Reed sent a blanket email to local septic contractors, discouraging them from working with Pruvell. In effect, the county made it nearly impossible for her to comply—even as they blamed her for failing to do so.

A broader agenda

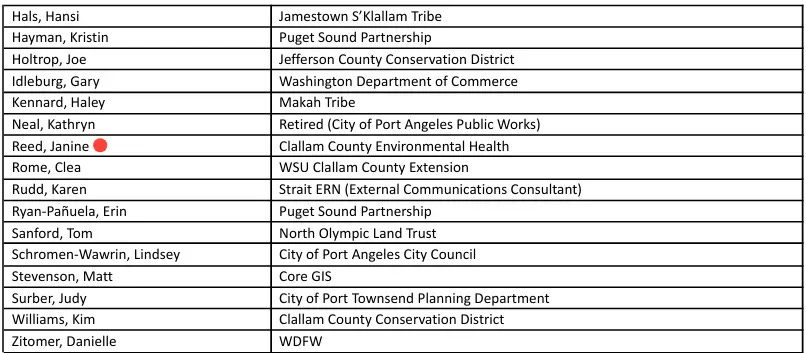

Interestingly, Reed also attended a 2021 workshop organized by the North Olympic Land Trust and hosted by the Strait Ecosystem Recovery Network—a nongovernmental organization (NGO) fiscally managed by the Jamestown Tribe with a focus on “repairing relationships” due to the effects of colonization. That meeting proposed that coastal private properties be acquired by the government at below-market rates in the name of climate change resiliency.

Eviction, it seems, doesn’t have to come through court orders—it can arrive in the form of unaffordable regulations and relentless pressure.

We’re beginning to see that play out along 3 Crabs Road, where the Clallam County Marine Resources Committee—a body with tribal representation—is calling for the removal of both the road and the homes along it.

Control through cost and regulation

When taken together, these efforts form a consistent pattern: new rules for wells, tighter control over septic systems, expanding conservation zones, and a growing web of interagency enforcement—all justified by “science,” “sustainability,” and “salmon recovery.” But the consequences are very real for residents already struggling to keep their homes.

It’s hard not to notice who benefits. And who doesn’t.

Last Sunday, readers were asked what they think is the most effective first step in addressing addiction and homelessness. Out of 303 votes:

68% said, “Stricter enforcement / accountability”

28% said, “Addiction treatment first”

3% said, “Housing first”

2% said, “Job training and employment first”

A few years ago I attempted to contact the Streamkeepers to get some information regarding Tumwater and Ennis creeks, hoping to learn the coliform load due to illegal encampments along creeks in Port Angeles.

I learned that there'd been no volunteers gathering stream data for a number of years yet the commissioners kept funding the activity per their budget records. When I contacted my commissioner about money spent for something that didn't exist I was told the program was being reconstituted and a coordinator was being sought.

Money for nothing and kicks for free.

Who knew what a toxic lead-mine of information was waiting to be uncovered?

I always 'felt' it but couldn't quite put my finger on it.

Here we are with the inevitable (according to founding Fathers) abusive tyrannical gov't they warned us about.

Property values are going to plunge in CC due to biased over-regulation and gov't abuse.

That might wake a few up...too late.

The immoral combination of corporations and state...(private/gov't)or (public/private) partnerships and the inevitable abuses is the exact thing we call FASCISM...on the 'face' of it, it seems to make sense and be a good deal for all...but it's not going to be a good deal for all.

It's going to lead to disaster and possibly civil unrest.

Buckle up..turbulence ahead.😱