All Show, No Go

Ten stories that show repeat problems and cities reversing course, while Clallam County insists the current model is working

December delivered a grim snapshot of where Clallam County is headed. A Montana man arrested three times in one month — each time for DUI-drugs — while carrying quantities of narcotics that prosecutors say point to trafficking. A viral video showing drug use in broad daylight steps from the courthouse. Meanwhile, cities across Washington — including Seattle — are changing their approach to drug consumption supplies and street disorder. This potpourri connects the dots between policy, incentives, and the uncomfortable reality that Clallam County’s “solutions” often look like permission slips.

Clallam Featured on Seattle News

Clallam County made statewide news in December, appearing on KOMO and KIRO News after a single individual was arrested three times in less than a month for drug-related offenses.

CC Watchdog has been tracking the bookings of 37-year-old Sergey Kubai of Kalispell, Montana, and details clarify why this case drew attention. It wasn’t one bad decision. It was a pattern: repeated impaired driving, escalating drug seizures, and behavior consistent with trafficking.

On December 7, troopers arrested Kubai for DUI-drugs and recovered significant quantities of suspected fentanyl, methamphetamine, heroin, and cannabis wax. On December 12, he was involved in a traffic collision and again arrested for DUI-drugs. A stolen firearm was located during a vehicle search, and a records check showed Kubai is a convicted felon in Montana.

Then came December 29 — another stop, another DUI-drugs arrest, and another discovery of suspected fentanyl. A follow-up search warrant executed the next day produced more suspected fentanyl, cocaine, methamphetamine, small amounts of crack cocaine and heroin, and digital scales.

Why would someone repeatedly return to Clallam County to drive impaired and carry large quantities of narcotics? Because, in a county that provides free drug paraphernalia, there are buyers — and where there’s demand, supply follows.

The most disturbing part is the simplest: three DUI-drugs arrests in one month means these are the people sharing Highway 101 with families, commuters, and school buses — at 55 miles per hour — while county leaders continue promoting a model that normalizes public drug use as the cost of “compassion.”

The irony is hard to miss. As Kubai sat in the Clallam County Jail for the third time in December, just down the hallway County Administrator Todd Mielke was telling concerned residents at a Commissioners’ Forum that the jail’s clinical services model is designed to stabilize individuals and connect them to recovery rather than cycle them through incarceration. At that same forum, Commissioner Mark Ozias assured the public that harm reduction is working and that there is “ample evidence” to support it.

The problem is not a lack of theory. It’s that while officials talk about success, the reality playing out on Clallam County roads and streets tells a very different story.

Broad Daylight, Behind the Bushes

A video filmed outside the Lincoln Street Safeway in Port Angeles is circulating widely, and it captures what many residents say they see routinely now — open drug use in broad daylight, treated as background noise.

In the footage, a lifelong local approaches two people using drugs in plain sight near the bushes by the Safeway gas station. One appears to be holding foil and has a straw in his mouth. A dog sits with them. Shoppers pump gas, buy groceries, and keep moving.

What gives the video its punch is what sits just behind the men: the courthouse, practically within shouting distance. It’s the same building where county commissioners are paid to govern — and where policies were approved to fund drug-use “supplies,” while residents are told to accept the resulting public disorder as the new normal.

For people who wonder why public trust is collapsing, this is why. Residents don’t need another PowerPoint about services delivered. They need an explanation for why illegal activity is playing out in the open, without consequence, in the heart of Port Angeles.

Why Isn’t Clallam County on This List?

Across Washington, local governments are starting to draw lines — sometimes directly around drug-supply distribution, sometimes indirectly through enforcement of camping, obstruction, and public disorder. The shift has been uneven, but it’s real.

Lewis County passed an ordinance restricting mobile syringe exchange operations and the distribution of certain harm-reduction supplies. Seattle’s 2026 budget includes language preventing city support for distributing “supplies for the consumption of illegal drugs,” while continuing needle exchange. Spokane moved to restrict the distribution of smoking paraphernalia unless Naloxone is provided. Everett and other jurisdictions have used permitting and “stay out” zones that limit street-level distribution in specific areas.

Separately, multiple cities have strengthened enforcement around camping and public encampments, particularly near schools, parks, business districts, and shelters. Spokane enacted an emergency ordinance prohibiting camping citywide. Tacoma expanded buffer zones. Lakewood authorized removals with 24 hours’ notice. Burien continues overnight bans. Auburn, Kennewick, and Richland have updated codes following recent court and policy shifts.

The consistent theme is this: leaders are acknowledging that permissive policies have downstream consequences — and they’re taking steps, however imperfect, to restore boundaries.

Which raises the local question: why aren’t Clallam County and it’s cities doing any of this? Why are we doubling down — with no serious public review — while other jurisdictions quietly reverse course?

Permanent Supportive Housing, Same Model as King County

Peninsula Behavioral Health’s North View complex in Port Angeles is described as permanent supportive housing — a model used at a much larger scale in King County by providers like Plymouth Housing.

Supporters describe permanent supportive housing as stable housing with services that help residents succeed. Critics point out that in places like Seattle, permanent supportive housing has frequently come with predictable outcomes: continued drug use, chronic disorder, and unsafe conditions for neighbors and other residents — with officials resisting enforcement on the grounds that housing must be protected at all costs.

If you want a glimpse of the debate, Jonathan Cho’s reporting offers a view into how “housing first” and low-barrier models have played out in practice — and why lawmakers continue funding them even when outcomes are ugly.

North View is still under construction. But the larger question is already here: what does Clallam County believe supportive housing should require — and what will it tolerate?

Blue Cities Are Quietly U-Turning on Drug Supplies

For years, cities like Seattle and San Francisco leaned into the distribution of “safer use” supplies — not just needles, but foil and pipes that can be used to smoke fentanyl. Now, at least some of those same jurisdictions are pulling back.

Seattle’s City Council, in its 2026 budget, included a provision that prevents city support for the purchase or distribution of supplies used for the consumption of illegal drugs, with an exception for needles. Councilmember Sara Nelson championed the idea, drawing a line between disease prevention and providing materials that effectively assist consumption.

This matters in Clallam County because county officials continue speaking as if the model is settled — as if there is “ample evidence” it works. Commissioner Mark Ozias said exactly that this week and said he’d be happy to share the evidence.

We’re waiting, Commissioner Ozias.

The Comments Are Where the Truth Slips Out

If you aren’t reading the comments under CC Watchdog articles, you’re missing half the story.

After reporting that the Sequim Food Bank executive director earns a six-figure salary and the organization now has a staff of eleven — while being led by its president, Commissioner Mark Ozias — one comment stood out for a different reason: the commenter described hearing a presentation suggesting anyone could use the food bank, regardless of need.

That’s not a small detail. It gets at a broader pattern in public services: when programs become “universal,” accountability and scarcity disappear. The mission shifts from emergency assistance to a parallel system that competes with working families who still pay full price.

Residents aren’t asking for cruelty. They’re asking for standards.

A Book With an Uncomfortable Thesis

Ginny Burton’s new book, The Gabriel Plan: Ten Points to Recover Our Nation, makes a claim that will resonate with anyone watching the homelessness and addiction system metastasize: the crisis is profitable, and the system is built to manage decline rather than demand transformation.

Burton writes from lived experience — decades in addiction, years inside government systems, and more than a decade clean — and says she has helped build a prison-based transformation program with a documented 97% success rate. Her argument is that we fund helplessness, remove consequences, and call it compassion — while nonprofit and institutional incentives reward continuation of the crisis.

Whether you agree with every point or not, the framing is worth considering: are we building a path out, or building an economy around staying stuck?

When “Private” Isn’t Really Private

In a decision that could reshape how transparency works in Washington, the state Supreme Court ruled that a private nonprofit can be subject to the Public Records Act when it operates like a government agency. In an 8–1 decision, the court found that DBIA Services — a nonprofit that handles parking, cleaning, and patrol services for downtown Seattle — functions as the equivalent of government. While technically private, DBIA is funded largely through mandatory assessments on property owners and performs services most people would reasonably expect the city itself to provide.

The case started when a Seattle resident requested records from DBIA, including employee compensation. Some documents were released, but pay information was withheld after the organization argued it wasn’t subject to public disclosure laws. The court disagreed. Writing for the majority, Justice Steven Gonzalez said DBIA met the legal test for being a functional arm of government and could not avoid transparency simply by operating under a nonprofit label.

For places like Clallam County, the ruling hits close to home. Many local nonprofits receive public money, carry out public functions, and shape policy — often while making decisions behind closed doors. This decision sends a clear message: if an organization is funded by the public and acting on the public’s behalf, it doesn’t get to sidestep accountability just because it calls itself “private.”

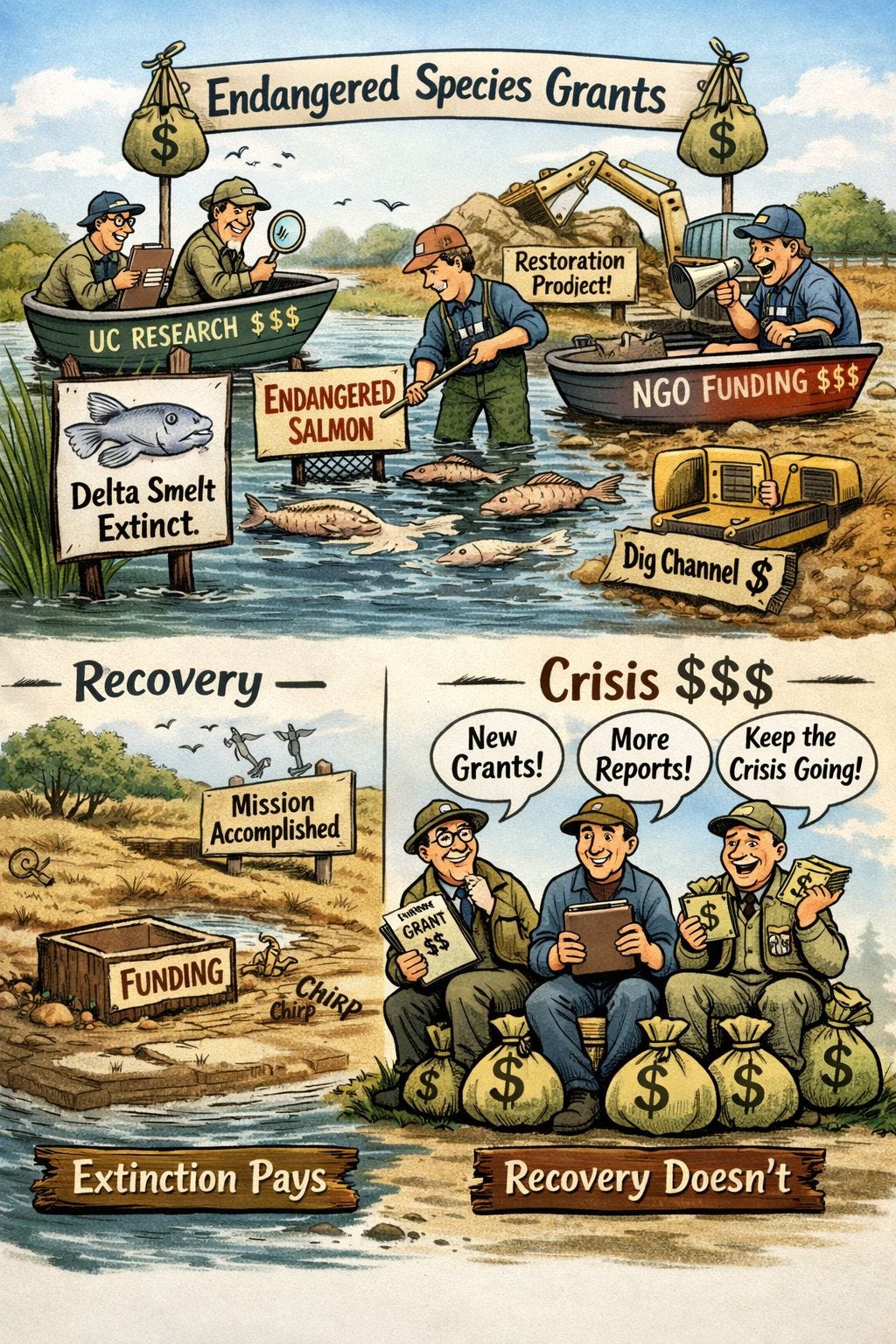

Follow the Incentives, Not the Promises

A LinkedIn post making the rounds about California’s Delta lays out what may be the most honest explanation for decades of “restoration” spending with worsening outcomes: incentives.

The author argues that endangered species generate grants, careers, studies, and regulatory expansion — while recovery sunsets funding and collapses programs. In that world, failure sustains careers. Success disrupts them.

It’s hard to read that and not think about how often Clallam County discussions around salmon recovery, habitat projects, and environmental spending sound the same: endless studies, endless interventions, endless urgency — and precious little accountability for results.

Towne Road. Conservation districts. Land trusts. “Restoration” defined as construction. Grants that never end. The parallels are not subtle.

Wedded to the Watchdog

Clallamity Jen is lining up an upcoming podcast interview — and this time she’s interviewing Doug, the Watchdog’s husband. She wants your questions, and he’s not previewing them beforehand. Your identity will be kept private.

Doug’s been given explicit instructions: nothing is off limits. From Towne Road to the daily reality of being connected to local controversy, Jen wants to hear what you want asked — and she’ll do it in her usual style.

Send your questions over the next few days to clallamityjen@gmail.com, and in the meantime, subscribe to Clallamity Jen’s Substack. It’s free — and around here, it’s one of the few places still willing to say the quiet part out loud with a laugh.

The commissioners did not answer yesterday's email. Today's question is:

Dear Commissioners,

How are you incorporating the lived experience of residents — particularly those who witness open drug use and repeat offenses — into your policy evaluations and future action plans regarding harm reduction?

All three commissioners can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov

The answers are all ways there and AI doesnt need to provide them: Zero tolerance, Tough love, no money for NGOs and zero conflict of interest in the leaders.