When Public Health Says “We Know,” What Should the Public See?

Harm reduction claims, public records, and evidence in Clallam County

In this clear-eyed review, Dr. Sarah Huling, EdD, MBA — a public health professional and West End Correspondent for CC Watchdog — takes a close look at Clallam County’s claims that its harm-reduction programs are “proven” and “working.” Rather than arguing ideology, Huling follows the paper trail, examining the county’s own public records. What she finds is straightforward: the services are real and widely accepted in public health, but the county has not shown local data or analysis to back up its strongest public statements about improved outcomes. The article draws an important line between tracking activity and measuring results — and asks county leaders to be clearer and more honest with the public about how success is defined and measured.

This review did not begin with opposition to harm reduction.

It began with a public meeting.

During the October 21, 2025, Clallam County Board of Health meeting, Public Health Officer Dr. Allison Berry described the county’s harm-reduction approach using several strong phrases: “best practices,” “proven interventions,” “we know they are working,” and that opioid-related outcomes “are improving.”

Those words matter.

In public health, they carry specific evidentiary meaning. When used in an official public meeting, they reasonably invite a simple question from residents: How do we know?

To answer that question, a Public Records Act request was submitted not for emails or internal discussions, but for existing records that would show:

What “best practices” were being relied upon?

What evidence made the interventions “proven”?

What data supported the claim that outcomes are improving locally?

What the county produced tells an important, yet incomplete, story.

What the County’s Records Clearly Show

The records demonstrate that Clallam County operates an active Harm Reduction Health Center (HRHC) that provides a wide range of services, including naloxone distribution, syringe services, wound care, safer-use supplies, referrals, and engagement support.

They also show that the county tracks activity metrics, including:

Naloxone doses distributed and reversals reported

Participant encounters

Syringes collected and distributed

Wound-care visits

Referrals to services

These activities are not controversial. They are consistent with well-established, evidence-based harm-reduction practices commonly recognized in public health.

For example:

Naloxone distribution is strongly supported as an effective tool for overdose reversal (Walley et al., 2013).

Syringe service programs are associated with reduced injection-related disease transmission and increased engagement with health services (Abdul-Quader et al., 2013).

Engagement through harm-reduction services can facilitate pathways into treatment (Hagan et al., 2000).

Nothing in the records contradicts the legitimacy of these approaches.

Where the Evidence Becomes Thinner

The problem is not that harm reduction lacks evidence.

The problem is that the county’s public claims go further than what its own local records actually show.

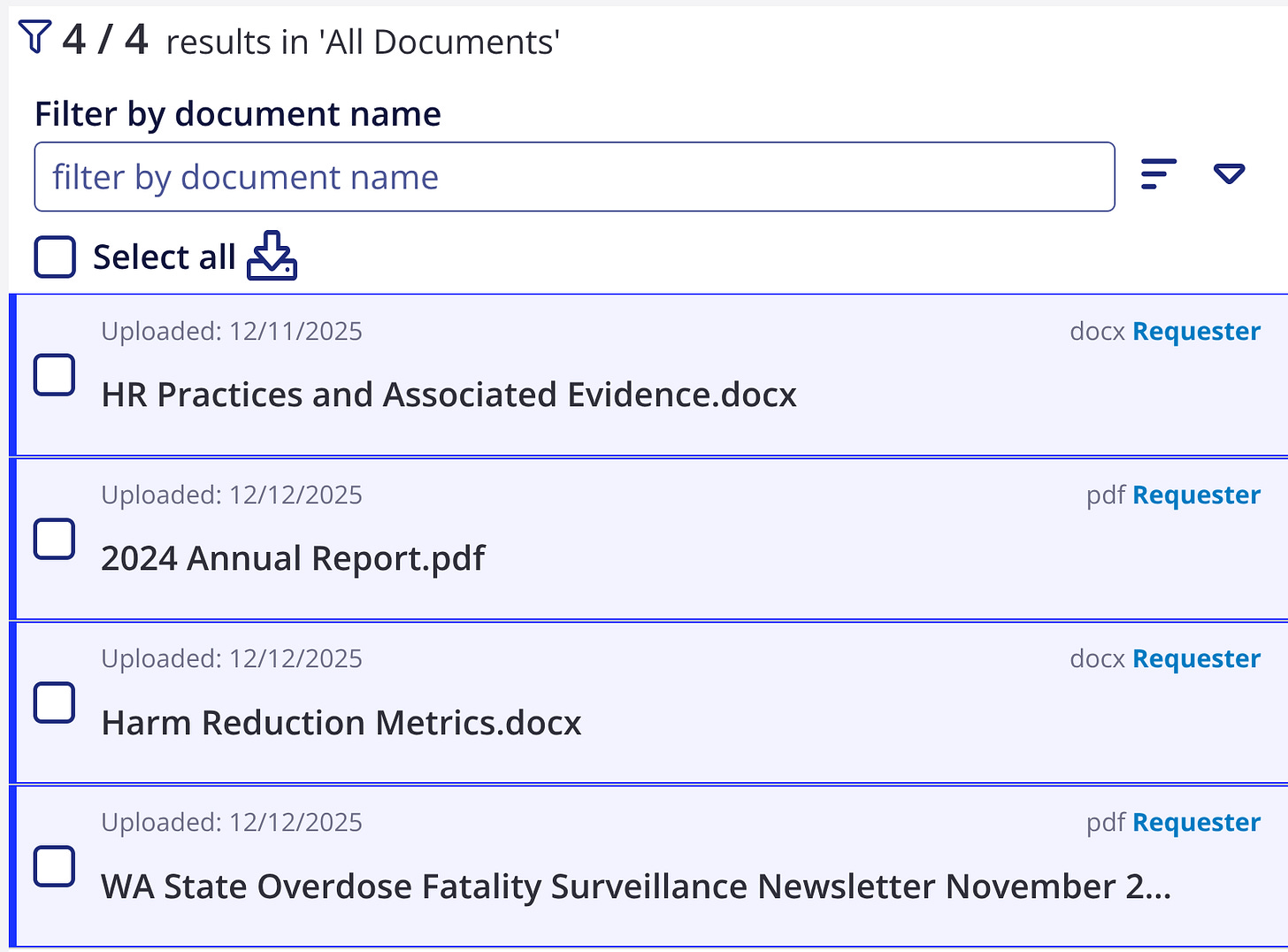

What the county’s own data show:

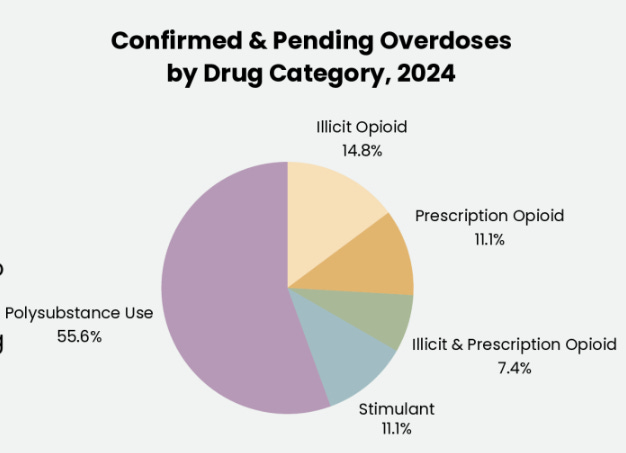

These charts summarize confirmed and pending overdoses in Clallam County (2024) by scene location and drug category, as reported in county records. Overdoses are heavily concentrated in Port Angeles, with fewer incidents in Forks and the West End, and most cases involve polysubstance use rather than a single opioid category.

Why this matters:

The data illustrate activity and distribution, but they do not, on their own, demonstrate improved population-level outcomes. This distinction is central to evaluating public claims that interventions are “proven” or “working.”

Activity Is Not Outcome

Most of the metrics the county tracks measure activity, not results — they show what services were provided, not whether conditions actually improved.

Modern public health evaluation separates results into three levels:

Outputs: what was delivered (such as naloxone kits handed out)

Intermediate outcomes: short-term changes (like safer-use behavior or starting treatment)

Population outcomes: long-term community effects (such as changes in overdose death rates)

The county’s documents focus almost entirely on the first level.

That matters because even recent research shows that while harm-reduction services do increase engagement and safety, the evidence that these activities lead directly to fewer overdose deaths across an entire community is more limited and depends heavily on local conditions. (Moran et al., 2024; Vickers-Smith et al., 2025).

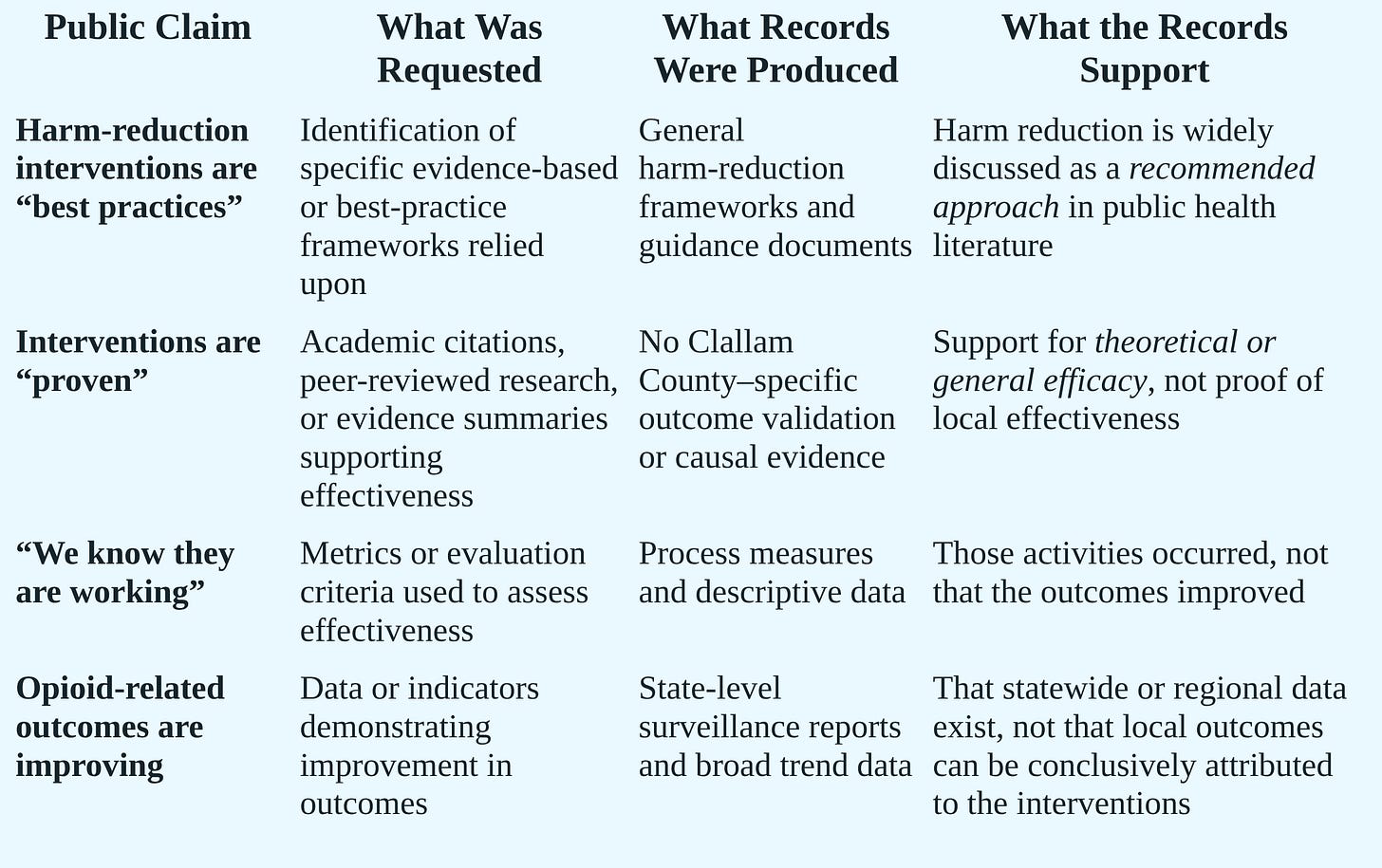

This table separates what was stated publicly from what the available records can substantiate, without challenging the intent or overall rationale of harm-reduction strategies.

Claims Made vs. Evidence Produced

“Proven” Requires More Than a Bibliography

The county did provide a list of academic studies, many of which are credible and widely cited. However, most of them fall into two main groups:

Older or foundational studies that explain how harm reduction works in general, such as syringe access reducing HIV transmission.

Intermediate-outcome studies that show programs can engage people or change behavior, but do not measure long-term community results.

Only a small number of the cited studies look directly at death rates, such as evaluations of community naloxone programs, national naloxone efforts, or access to treatment in jails and prisons.

Importantly, none of the records show a local analysis linking Clallam County’s harm-reduction programs to fewer overdose deaths.

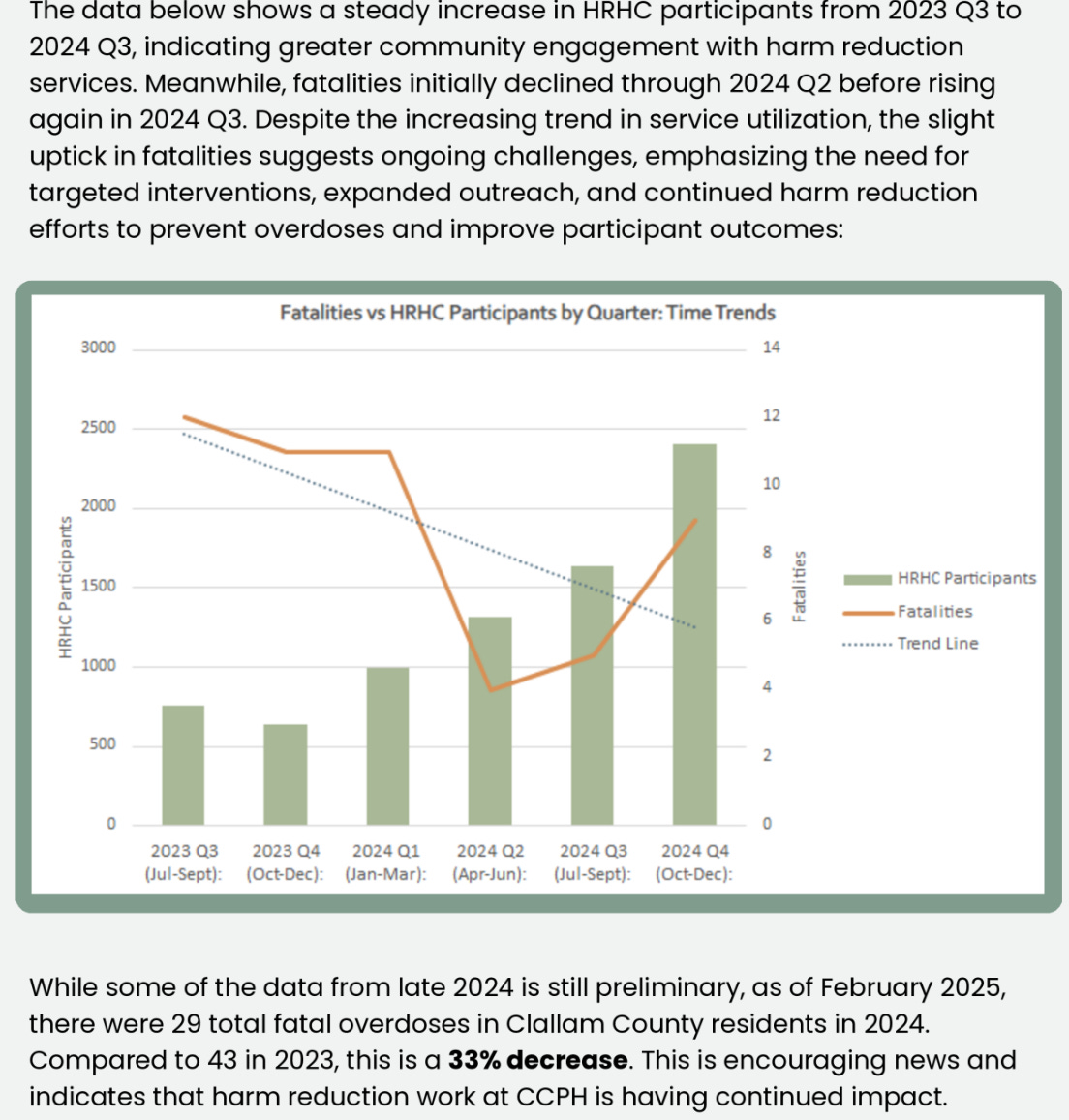

What this chart (below) shows:

This figure plots Harm Reduction Health Center (HRHC) participant counts alongside fatal overdoses by quarter from late 2023 through 2024. Participation increases steadily over time, while fatalities decline through mid-2024 before rising again later in the year.

What it does not show:

The chart displays two trends on different scales without an analytical method connecting them. It does not establish causation, control for broader state or national trends, account for seasonality, or explain how participation levels relate to changes in fatal overdose risk. As presented, it shows coinciding trends rather than demonstrated outcomes.

Even strong supporters of harm reduction now warn against overstating certainty without clear evaluation. Recent public health research stresses the need for clear goals, defined outcomes, and transparent trend analysis — especially in today’s fentanyl- and xylazine-driven drug environment. (Cano et al., 2024; Moran et al., 2024).

“We Know They Are Working” — But How?

Perhaps the most consequential statement in the meeting was: “We know these interventions are working.”

Knowing requires method. Yet the records produced do not include:

A defined analytic approach,

Baseline comparisons,

Trend analyses, or

Criteria explaining how activity metrics translate into “working.”

The county does reference state overdose surveillance data and asserts that Clallam’s relative ranking has improved. But the records do not show:

Which dataset was used for that conclusion

Which years were compared

Whether rates were age-adjusted

Whether statewide trends were accounted for

Without that information, the claim cannot be independently verified, a basic expectation when public officials speak with confidence.

What Modern Public Health Practice Expects

This is not a radical critique.

Recent harm-reduction research places growing importance on clear, transparent evaluation, not just providing services. Today’s public health frameworks say agencies should be able to plainly explain:

What outcomes they are trying to improve

How their programs are supposed to achieve those results

How progress is being measured

What is still uncertain or unknown (Moran et al., 2024)

Under that standard, statements like “we know it’s working” would be replaced with something more precise and more credible, such as:

“We are seeing more people engaged in services and more overdose reversals. Broader community impacts are tracked through state data and are still being evaluated.”

That kind of language does not weaken public health. It strengthens trust.

Why This Matters to Clallam County Residents

Residents are not asking for perfection.

They are asking for:

Honesty about what is known and what is not

Clarity about how conclusions are reached

Accountability when strong claims are made

If harm-reduction efforts are improving outcomes locally, the data should be visible and easy to understand. If evaluation is still underway, that should be stated plainly.

Either way, confidence should follow evidence — not precede it.

Call to Action: Defining Success Together

Public health professionals and residents often mean different things when they talk about “success,” and both viewpoints matter.

Public health tends to measure success through engagement, overdose reversals, and services provided. Residents tend to measure success by what they see and experience every day — safer public spaces, fewer people incapacitated in public, and communities where children are not regularly exposed to drug use or overdoses.

These goals are not in conflict, but they do require clear definitions.

If Clallam County believes its harm-reduction efforts are improving outcomes, residents should be able to clearly see how success is defined and how progress is measured — both for public health results and for community impacts.

For residents who want to be part of that conversation, they can take one or two simple steps:

Email your Public Health Officer

Residents may email Dr. Allison Berry directly at allison.berry@ClallamCountyWA.gov

A simple question is enough:

“How does Clallam County define success for harm reduction, and how are both public health outcomes and community impacts being measured?”

Attend or Participate in a Board of Health Meeting

Board of Health — Regular Meetings

🕜 1:30 PM

📅 3rd Tuesday of each month

📍 Commissioners’ Board Room #160

Clallam County Courthouse

Residents may also participate via Zoom:

🔗 https://zoom.us/j/93573435754

Public health works best when residents are informed participants and when community experiences and professional expertise are brought together in the same conversation.

Defining success together is how trust is built.

Dr. Sarah describes herself as, “From the trenches, X-ray vision, ultrasonic super-tech powers, and just enough formal education to be dangerous. Cape optional. Receipts required. Curiosity and evidence over rhetoric.”

References

Abdul-Quader, A. S., Feelemyer, J., Modi, S., Stein, E. S., Briceno, A., Semaan, S., … Des Jarlais, D. C. (2013). Effectiveness of structural-level needle/syringe programs to reduce HCV and HIV infection among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 103(2), 316–331. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300819

Bird, S. M., McAuley, A., Perry, S., & Hunter, C. (2016). Effectiveness of Scotland’s national naloxone programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: A before-after study. The Lancet, 386(10004), 2195–2203. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00265-3

Cano, M., Oh, S., Salas-Wright, C. P., & Vaughn, M. G. (2024). Xylazine involvement in overdose deaths in the United States. JAMA Network Open, 7(2), e2356789. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.56789

Green, T. C., Clarke, J., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Marshall, B. D. L., Alexander-Scott, N., Boss, R., & Rich, J. D. (2018). Postincarceration fatal overdoses after implementing medications for addiction treatment in a statewide correctional system. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(4), 405–407. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4614

Hagan, H., McGough, J. P., Thiede, H., Hopkins, S., Duchin, J., & Alexander, E. R. (2000). Reduced injection frequency and increased entry and retention in drug treatment associated with needle-exchange participation in Seattle. American Journal of Public Health, 90(10), 1628–1632.

Moran, S., Guta, A., et al. (2024). Evaluating harm reduction interventions: Aligning practice with outcomes in an evolving drug supply. Harm Reduction Journal, 21(12). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-024-00987-x

Vickers-Smith, R., LaRue, L., et al. (2025). Fentanyl test strip use and overdose risk-reduction behaviors among people who use drugs. JAMA Network Open, 8(1), e2456789. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.56789

Walley, A. Y., Xuan, Z., Hackman, H. H., Quinn, E., Doe-Simkins, M., Sorensen-Alawad, A., … Ozonoff, A. (2013). Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: Interrupted time series analysis. BMJ, 346, f174. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f174

Today's email to commissioners (they did not answer yesterday's):

Dear Commissioners,

Public Health has said these harm-reduction programs are working. What local evidence are you relying on to say that—beyond counts of supplies handed out or services provided? Can you point residents to data that actually shows fewer overdoses, better recovery outcomes, or safer communities here in Clallam County?

All three Clallam County Commissioners can be reached by emailing the Clerk of the Board at loni.gores@clallamcountywa.gov.

Excellent article. Even with citations to quell the inevitable eye rolls from the medical and public health establishment.

Allison Berry proved herself to be one of the most inept public health officials in the country during COVID. Her direct ties to John’s Hopkins University tells you she has zero critical thinking skills and parrots the science coming out of the most dangerous institutions in the world.

I think it’s time for a new public health officer. One that can write and cite sources other than John’s Hopkins and the Gates Foundation. One that actually lives in Clallam county.