The Hidden Freight Surcharge and Who Benefits

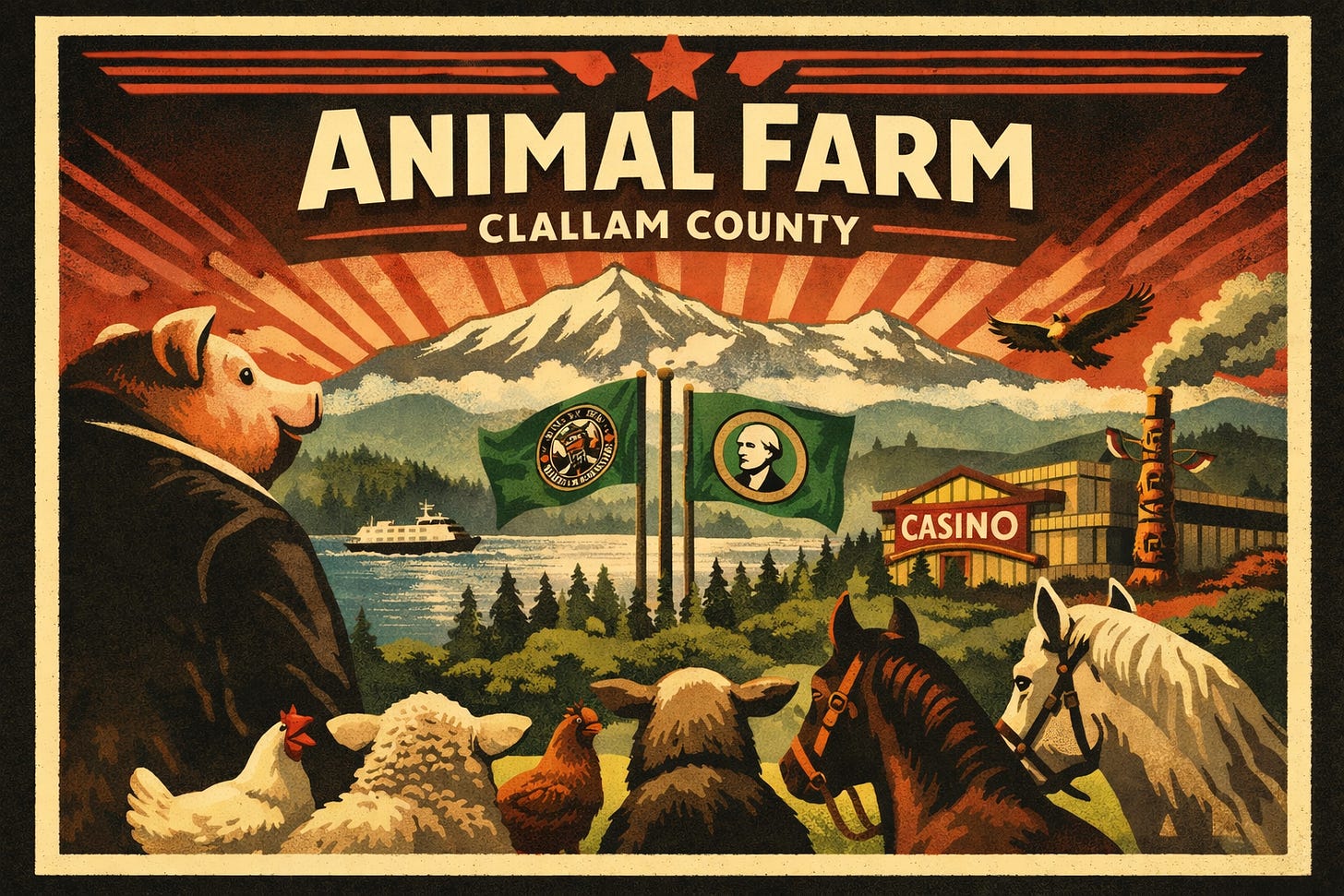

The Climate Commitment Act picks winners and losers on the Olympic Peninsula

On the Olympic Peninsula, the Climate Commitment Act doesn’t feel like an abstract carbon policy—it feels like a quiet markup on groceries, gas, and building supplies, because nearly everything we buy gets here by truck. Families scraping to fill a tank pay first, and pay again at the checkout line. But while the public absorbs the cost, the Department of Commerce advertises CCA-backed programs that—by design, eligibility rules, or “separate track” meetings—steer a disproportionate share of the upside to tribal governments and tribal entities. If this is “equity,” why does it look like a system where everyone pays, but only some are positioned to win?

The Peninsula Penalty: When “Carbon Policy” Becomes a Truck Surcharge

In Seattle and Olympia, the Climate Commitment Act (CCA) is marketed as a clean-energy investment strategy. On the Olympic Peninsula, it functions more like a hidden freight surcharge.

Food, fuel, medicine, appliances, building materials—almost everything here arrives by truck. When fuel costs rise upstream, those costs don’t stay abstract. They land on grocery shelves, gas pumps, and contractor invoices.

Raising transportation costs doesn’t just affect corporations. It hits the single parent commuting to work in Forks, the retiree on a fixed income in Sequim, and the family trying to finish a basic home repair without running up a credit card bill.

This is the part rarely mentioned: carbon costs ride the supply chain. They show up one receipt at a time.

A “Nonpartisan” Dais Can’t Campaign for State Taxes

When elected county officials promote statewide tax-and-spend policies from the local dais, that’s not neutral governance—it’s political advocacy backed by public office.

Commissioner Mark Ozias publicly pushed for the Climate Commitment Act from the commissioners’ dais. That alignment is notable given that his campaign’s largest contributor, the Jamestown Corporation, has received millions of dollars through CCA-funded programs.

Residents can disagree about the policy itself, but the process matters. There is a clear line between representing constituents locally and using the authority of office to influence statewide outcomes.

County government is supposed to serve everyone, not tell voters how to think—or how to vote.

Follow the Incentives: Who Benefits When Costs Rise?

This is where the debate stops being theoretical.

Households pay more, while institutions positioned to navigate state systems gain access to grants, contracts, and influence over how money is distributed. The Department of Commerce doesn’t just administer funds—it co-designs programs, rewrites eligibility, and convenes workgroups that shape where money flows next.

When the largest political contributors are also deeply embedded in these systems, it’s reasonable for the public to ask whether this is simply climate policy—or political economy.

Commerce’s CCA-Funded “Opportunities”

Commerce presents CCA spending as inclusive, but in practice it operates on two tracks.

EV Charging and the “Tribal Workgroup” Track

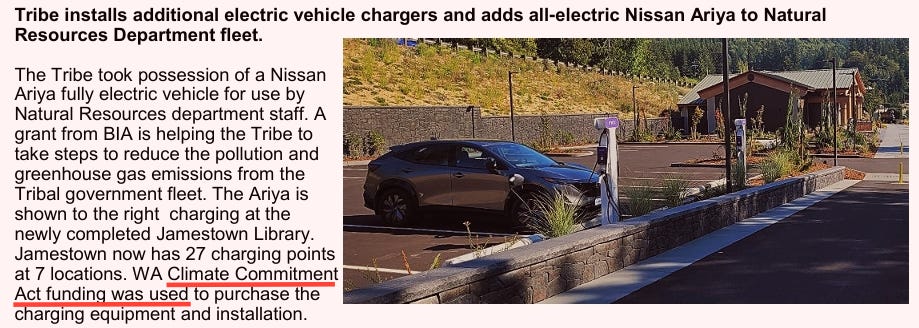

Commerce highlights tribal participation in EV charging grants and convenes a monthly Tribal Workgroup to redesign future funding—covering eligibility, timelines, and grant sizes.

That isn’t illegal. But it’s not neutral.

It gives some participants a seat at the table before the rules are finalized, while everyone else sees the program only after the design is complete.

Tribe-Only Programs Aren’t Subtle

Some programs don’t even claim to be universal. The Tribal Electric Boats Program is exactly what it sounds like—limited to tribes and tribal enterprises.

That may be a policy choice. But it cannot be sold as broadly equitable when the funding comes from a system that raises costs for everyone.

Separate Bidder Sessions, Separate Rules

Commerce frequently holds separate pre-proposal sessions for tribes, including sessions that are not recorded, while general sessions are.

If public money is involved, the public has a right to ask:

Why are some applicants given a different lane—and why is it less transparent?

The $10 Power Bill Question

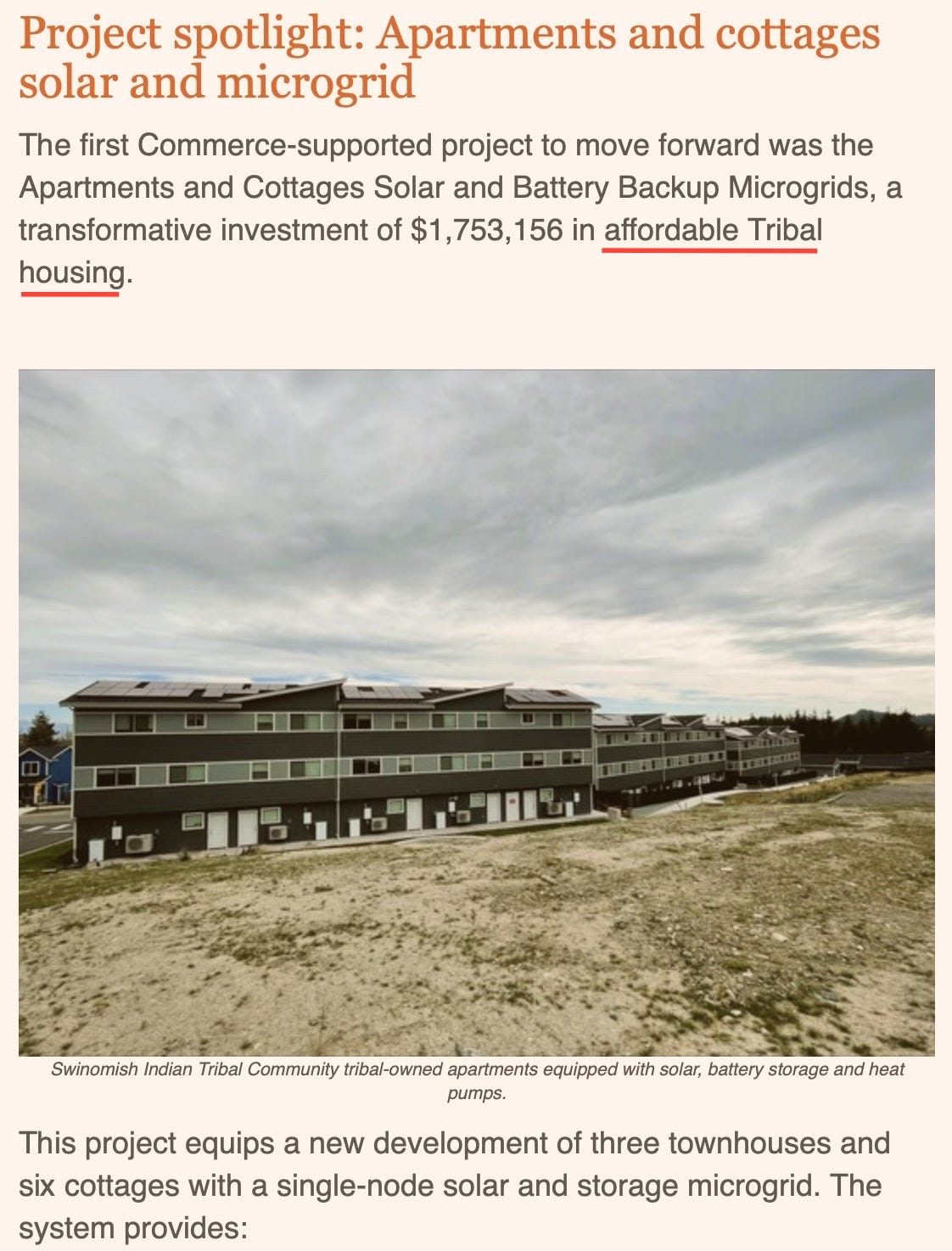

Commerce’s own spotlight on Swinomish clean-energy projects describes CCA-funded investments that dropped some household power bills from roughly $160 to as low as $10.

That success story raises an obvious question for working families:

How does a non-tribal household access the same benefits?

There is no clear answer—because the pathway isn’t the same.

Salmon Recovery Grants and “Co-Management” Language

Commerce’s salmon recovery grants openly state they are funded by the CCA and emphasize tribal co-management.

If these are statewide public benefits, then eligibility, accountability, and governance should be equally clear for everyone. Instead, some partners help set direction while others absorb the regulatory and financial burden.

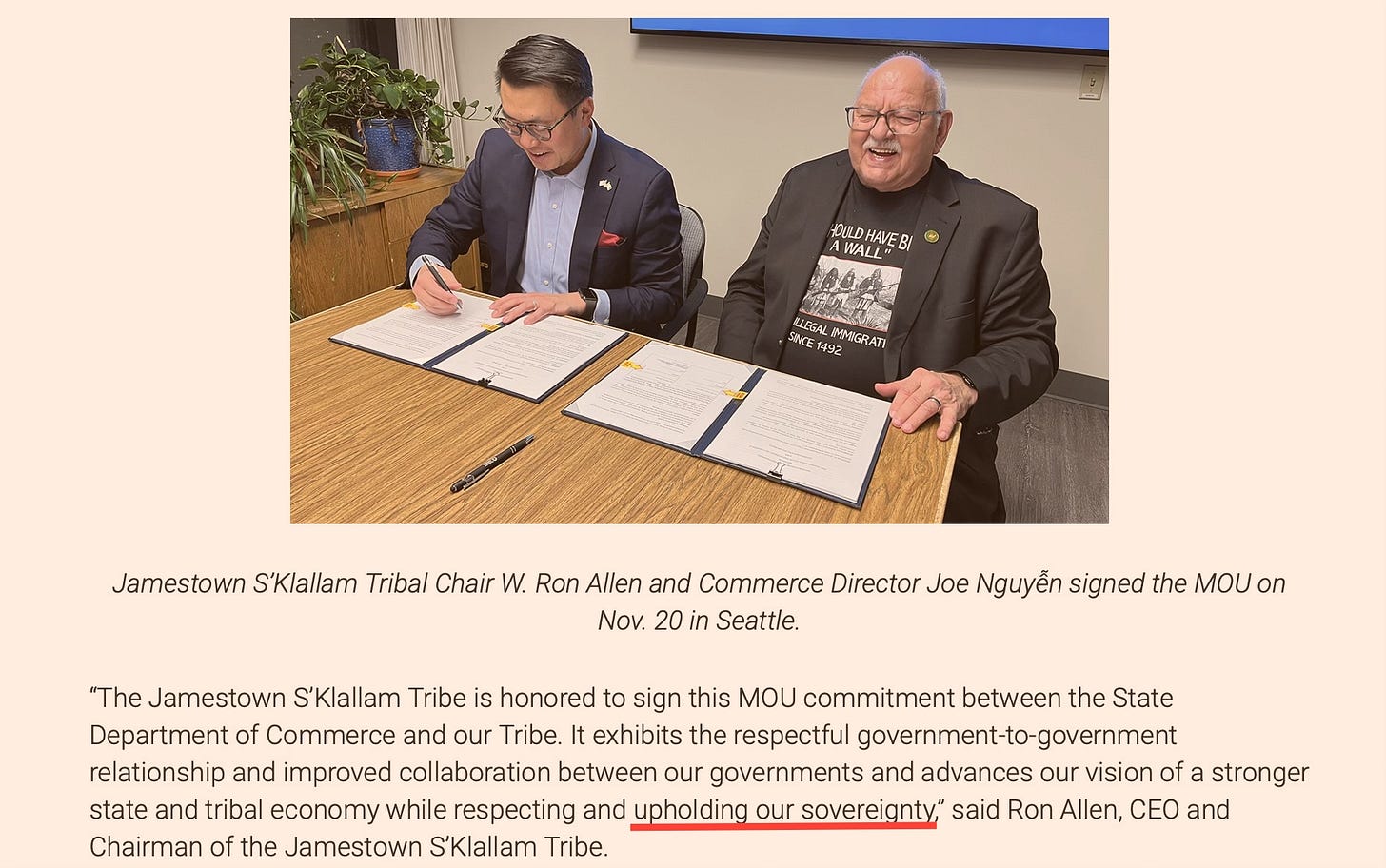

MOUs and “Data Sovereignty”

Commerce promotes its growing list of tribal MOUs as a success—agreements that streamline contracting and “honor data sovereignty.”

Translated plainly: faster access and fewer barriers for some, paired with reduced public visibility into how money is used.

That creates an obvious tension. If taxpayers fund these programs, why shouldn’t accountability be consistent?

Respecting sovereignty does not require building systems where public dollars meet private oversight.

Everyone Pays—Only Some Benefit

The uncomfortable question many residents ask is whether this system is fair.

If eligibility is based on race or ancestry, constitutional concerns arise. If eligibility is based on legal or political status, the state will argue it’s lawful.

But for those excluded, the lived reality is the same: they pay more, and they don’t qualify.

The result is a two-tier system:

Everyone absorbs higher costs.

Selected entities receive preferential access to CCA-funded benefits.

That structure cannot sustain public trust.

The Hypocrisy of “Equal Access”

Commerce repeatedly claims that “transparent access to the same information” is central to equity—while simultaneously operating:

tribe-only programs

separate bidder sessions

non-recorded meetings

streamlined contracting for some

design workgroups dominated by prior recipients

That isn’t equal access. It’s priviledged access.

The Questions the Peninsula Deserves Answered

If the Climate Commitment Act is going to operate like a hidden gas tax in rural Washington, residents deserve clear answers:

How much of the cost burden falls on rural supply chains?

How much CCA funding is realistically accessible to non-tribal households and small businesses?

Why are some applicant tracks separated—and some meetings unrecorded?

What accountability standards apply to every recipient?

Until those questions are answered, the CCA won’t look like climate policy on the Olympic Peninsula.

It will look like a regressive cost increase paired with a selective grant economy—and a government asking struggling residents to pay more, while quietly deciding who gets paid back.

Good Governance Daily Proverb:

Good governance distinguishes between moral expression and problem-solving.

Caring motivates policy—but evidence, transparency, and feedback determine whether it actually works.

It's all wrapped up as climate change because it makes people feel good and think that it's helping the crisis we're told is happening. What it really is takes some discernment and my take is that it's all about income redistribution and buying votes. If you've ever seen the Washington State Department of Commerce Facebook page it becomes clear that it's nothing but another taxing mechanism frittered away by popular policy in Olympia, and supported by the likes of Ozias.